Introduction

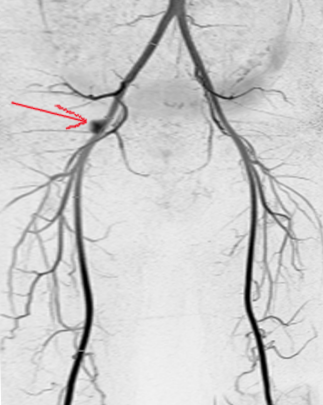

A Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm consists of an outpouching of 1 or 2 layers of the vessel wall. On the other hand, a true aneurysm involves all 3 layers, including the intima, media, and adventitia (see Image. Femoral Artery Aneurysm). Clinically, it may present with pulsatile hematoma, pain, ecchymosis, or active extravasation. In chronic scenarios, once a fibrous capsule has been formed, it may present with a persistent flow communicating with the arterial lumen. Pseudoaneurysm clinical progression varies; its complications depend on the size, mechanism of injury, duration, patient comorbidities, and neck diameter. Potential complications include expansion, rupture, embolization, extravasation with arterial wall compression, and ischemia. Clinical examination should raise a high index of suspicion once a pulsatile mass can be felt, especially when a patient reports a recent intervention.[1][2][3]

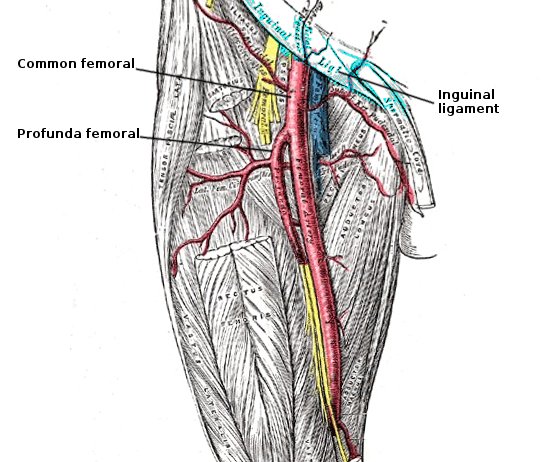

The common iliac artery gives off 2 major branches; the internal iliac artery (IAA) provides blood supply to the pelvis while the external iliac artery (EIA) is the main blood supply to the foot (see Image. Femoral Artery Anatomy). Once it passes the inguinal ligament, EIA becomes the common femoral artery (CFA). CFA then bifurcates into the profunda artery and superficial femoral artery (SFA). Understanding the anatomic landmarks clearly before making an arterial puncture is important. It is common practice to identify these important landmarks and use sonographic guidance for safe cannulation of the arterial lumen. It is also advisable to make the arterial entry into the CFA at a level where external compression would prevent any hematoma or PSA formation. The ideal entry-level would then be above the femoral head. Hence, draw the anatomic landmarks consisting of a line 1 fingerbreadth below a line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) with the pubic symphysis and a second line at the inguinal crease. Between these 2 lines, the practitioner should find the common femoral artery overlying the femoral head for easy compressibility. Palpate for a point of maximal impulse, which is the entry point.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Femoral PSA can typically be caused by any form of percutaneous intervention that uses the femoral artery as its entry point. Classically, interventions after cardiac catheterization for coronary stenting have been implicated as the culprit. However, any form of femoral artery cannulation and sheath introduction can potentially cause arterial wall dissection with resultant PSA. Hence, ultrasound-guided cannulation with a Seldinger technique under fluoroscopic guidance becomes paramount in any endovascular intervention. Certain risk factors may contribute to PSA formation, for example, the use of large sheath size, poor technique, patient body habitus and obesity, need for anticoagulation, female gender, and patient on hemodialysis. It is also implicated that interventions performed for therapeutic reasons are associated with a higher number of PSA formations than diagnostic ones, as the former typically require a larger size sheath.[4][5][6]

True femoral artery aneurysms are very rare and are mostly found in individuals over the age of 65. They are usually unilateral but may be bilateral in 10% of cases. In at least 30% of cases, the true femoral artery aneurysm is associated with an aneurysm elsewhere in the body. Unlike pseudoaneurysms, the risk of rupture is low; however, these aneurysms can form thrombosis and cause limb ischemia.

Epidemiology

As mentioned, PSAs are the most common complication after percutaneous procedures performed by a cardiologist, interventional radiologist, or vascular surgeon. Some series have reported incidence from 0.5% to up to 9%. There are other rare causes, such as surgical intervention or blunt and penetrating trauma. A few case reports reported femoral artery PSA due to slipped capital femoral epiphysis treatment. However, percutaneous interventions are the leading cause of PSA formation.[7]

History and Physical

While examining a patient for a femoral PSA, the clinician should perform a full vascular exam of the patient and a detailed medical history, including HTN, smoking, hyperlipidemia, recent vascular interventions, or recent/remote trauma. The examiner should then perform a comprehensive vascular examination starting with a cardiovascular examination, followed by listening to any bruit in the neck, recording and examining any peripheral pulses in both upper and lower extremities, and any investigating for pulsatile abdominal mass. A detailed examination should be tailored to a patient with a pulsatile mass in the groin. A patient at this stage should not be mistaken as having an inguinal hernia, as both entities could present with a bulge and pain. A bruit, however, would differentiate between the 2 as it is characteristic of PSA instead of an inguinal hernia.

Evaluation

Imaging modalities for PSAs include a duplex ultrasound (DUS). Usually, the first test one should obtain if PSA is suspected. DUS carries a sensitivity of 92% to 96%. Findings on DUS indicate PSA would consist of a “to-and-fro flow” between the arterial lumen and femoral artery. Ideally, the DUS includes the dimensions and size of the sac and the neck, and treatment is based on those dimensions. Proximal and distal arteries should also be evaluated for thrombus extruding from the aneurysmal sac. Whenever a surgical intervention is planned, CT angiography can be used for pre-operative planning.[1][8][9]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of femoral PSA includes open surgical repair, ultrasound-guided compression, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, coil embolization, and covered stent placement.[10][11][3](A1)

Surgical repair of PSA is an option when a concomitant arterio-venous fistula exists. It should also be considered when there is ongoing hemodynamic instability or limb ischemia. Surgical principles consist of controlling the artery proximally and distally and primary repair of the arterial defect. When hemorrhagic shock ensues, digital compression of the bleeding site should be performed first, followed by vascular control and primary arteriography. Sometimes a retroperitoneal incision may be required for obtaining external iliac artery exposure in large PSA. If the primary repair cannot be successfully achieved, a vein graft should be used to reconstruct the arterial system.

Ultrasound compression visualizes the neck of the PSA and applies pressure until the neck is occluded. If a PSA is present, care should be taken to avoid compressing the femoral artery while performing compression. When the neck is less than 2 cm, PSA is treated successfully with ultrasound. Technical failures with this method have been estimated up to 10% to 30%. If this occurs, alternative treatment should be sought.

Ultrasound thrombin injection is also a minimally invasive procedure that can be performed at the bedside under local anesthesia. To qualify for this treatment modality, the PSA should typically have a long neck that is narrow and easily seen on ultrasound. A spinal needle (22 gauges) is inserted into the sac, and under continuous visualization, thrombin is injected into the sac. The needle is visualized during the entire procedure to avoid accidental thrombin injection into the arterial system. Approximately 100 to 500 U/ml of thrombin is injected into the sac at about 0.1mL increments until thrombosis is achieved. A technical failure between 5% and 10% has been reported using this method, providing neck anatomy is adequate.

Another minimally invasive treatment is endovascular treatment, which could entail coil embolization or covered stent deployment. Complications include treatment failure and PSA formation since the contralateral groin is often used to gain access.

Complications with any treatment mentioned above include thrombosis of both the venous and arterial systems. Embolization into the distal arterial tree can occur in 2% to 4% of cases; hence, a thorough pulse examination should be carried out prior to and after the procedure. If distal embolization is suspected, a Fogarty catheter should be passed proximally and distally. Once the flow has been restored, the nurse should be asked to palpate the pulses in the feet.

If the patient has a true aneurysm, then repair is not recommended. The aneurysm should be resected, and a prosthetic graft should be inserted.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for femoral artery pseudoaneurysm include the following:

- Constipation

- Diverticulitis

- Ectopic testis

- Femoral artery aneurysm

- Gastroenteritis

- Inguinal lymph node

- Lipoma

- Osteoarthritis

- Psoas abscess

- Psoas bursa

- Saphena varix

Prognosis

The prognosis for most patients with treatment is good. However, without treatment, the pseudoaneurysm can continue to expand, and there is also a risk of rupture. True aneurysms have the potential to induce limb ischemia. In patients who have an invasive procedure at the groin, often there is marked bleeding in the groin, which may take months to resolve. Because the blood is in the connective tissue, inserting a drain is futile. It is important to understand that most patients who undergo a percutaneous procedure for heart disease also have other co-morbidities. Thus, most of these patients need close monitoring.

Complications

The complications that can manifest with femoral artery pseudoaneurysm are as follows:

- Embolization

- Ischemia and gangrene of the leg

- Blue toe syndrome

- Rupture

- Venous compression

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Usually, a pulse examination post-intervention should be documented and compared with pre-intervention. An ultrasound study should be performed 1 hour after treatment to demonstrate successful sac closure. In addition, a clinic appointment 1-week post-intervention should be scheduled to evaluate for skin necrosis, pulse status, and sac closure with a hand-held ultrasound probe.

Consultations

Consultations that are typically requested for patients with this condition include the following:

- Vascular surgeon

- Interventional radiologist

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Even though true femoral artery aneurysms are rare, pseudoaneurysms of the femoral artery are relatively common on the cardiology floor, where patients often undergo cardiac catheterization. A nurse usually does the monitoring and management of femoral artery aneurysms. Once a patient returns from a cardiac catheterization lab, the nurse should monitor the groin site for bleeding and assess the pulses in the leg. The groin should be observed for expansion and ecchymosis. Any changes in the groin size or loss of distal pulses should result in an immediate call to the patient's physician. Today, the management of femoral artery aneurysms involves the placement of a stent, ultrasound-guided compression, or surgery. While surgery is the gold standard, some patients may be too ill to undergo the procedure and may benefit from a less invasive percutaneous procedure. After the procedure, the patient's distal pulses have to be monitored. Some patients may be placed on a heparin drip, so the coagulation parameters must be monitored. Before discharge, patients should be urged to lose weight, discontinue smoking, control their blood pressure and diabetes, and exercise regularly. Close communication between the team members is essential to improve outcomes.[12][13][14]

Outcomes

The majority of patients with a femoral artery aneurysm have a good outcome, provided they lower the risk factors for peripheral vascular disease. Unfortunately, for those who do not change their lifestyle, peripheral vascular disease is progressive and often leads to limited exercise endurance and ischemic changes in the limbs. For those who throw an emboli distally, some people do end up with toe amputations.[1][15]

Media

References

Dwivedi K, Regi JM, Cleveland TJ, Turner D, Kusuma D, Thomas SM, Goode SD. Long-Term Evaluation of Percutaneous Groin Access for EVAR. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2019 Jan:42(1):28-33. doi: 10.1007/s00270-018-2072-3. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30288590]

Moonen HPFX, Koning OHJ, van den Haak RF, Verhoeven BAN, Hinnen JW. Short-term outcome and mid-term access site complications of the percutaneous approach to endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (PEVAR) after introduction in a vascular teaching hospital. Cardiovascular intervention and therapeutics. 2019 Jul:34(3):226-233. doi: 10.1007/s12928-018-0547-4. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30259385]

Noori VJ, Eldrup-Jørgensen J. A systematic review of vascular closure devices for femoral artery puncture sites. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Sep:68(3):887-899. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.05.019. Epub 2018 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 30146036]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRaikar MG, Gajanana D, Usman MHU, Taylor NE, Janzer SF, George JC. Femoral pseudoaneurysm closure by direct access: To stick or not to stick? Cardiovascular revascularization medicine : including molecular interventions. 2018 Dec:19(8S):41-43. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2018.04.008. Epub 2018 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 29804798]

Luo Y, Zhu J, Dai X, Fan H, Feng Z, Zhang Y, Hu F. Endovascular treatment of primary mycotic aortic aneurysms: a 7-year single-center experience. The Journal of international medical research. 2018 Sep:46(9):3903-3909. doi: 10.1177/0300060518781651. Epub 2018 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 29962258]

Ierovante N, Sanghvi K. Prophylactic Ipsilateral Superficial Femoral Artery Access in Patients With Elevated Risk for Femoral Access Complications During Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2018 Aug 13:11(15):e123-e125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.05.004. Epub 2018 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 30031716]

Lamelas J, Williams RF, Mawad M, LaPietra A. Complications Associated With Femoral Cannulation During Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017 Jun:103(6):1927-1932. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.098. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28017338]

Chun EJ, Ultrasonographic evaluation of complications related to transfemoral arterial procedures. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2018 Apr [PubMed PMID: 29145350]

Aurshina A, Ascher E, Hingorani A, Salles-Cunha SX, Marks N, Iadgarova E. Clinical Role of the "Venous" Ultrasound to Identify Lower Extremity Pathology. Annals of vascular surgery. 2017 Jan:38():274-278. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.05.113. Epub 2016 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 27531093]

Fokin AA, Kireev KA. [Algorithm of treatment policy for a femoral artery false aneurysm]. Angiologiia i sosudistaia khirurgiia = Angiology and vascular surgery. 2018:24(2):195-200 [PubMed PMID: 29924791]

Mufty H, Daenens K, Houthoofd S, Fourneau I. Endovascular Treatment of Isolated Degenerative Superficial Femoral Artery Aneurysm. Annals of vascular surgery. 2018 May:49():311.e11-311.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.11.038. Epub 2018 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 29458083]

Kasthuri R,Karunaratne D,Andrew H,Sumner J,Chalmers N, Day-case peripheral angioplasty using nurse-led admission, discharge, and follow-up procedures: arterial closure devices are not necessary. Clinical radiology. 2007 Dec [PubMed PMID: 17981169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee TL, Bokovoy J. Understanding discharge instructions after vascular surgery: an observational study. Journal of vascular nursing : official publication of the Society for Peripheral Vascular Nursing. 2005 Mar:23(1):25-9 [PubMed PMID: 15741962]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGross KA. Ultrasonographic diagnosis and guided compression repair of femoral artery pseudoaneurysm: an update for the vascular nurse. Journal of vascular nursing : official publication of the Society for Peripheral Vascular Nursing. 1999 Sep:17(3):59-64 [PubMed PMID: 10818882]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePanfilov DS, Kozlov BN, Panfilov SD, Kuznetsov MS, Nasrashvili GG, Shipulin VM. [Puncture treatment of pseudoaneurysms of femoral arteries with the use of human thrombin]. Angiologiia i sosudistaia khirurgiia = Angiology and vascular surgery. 2016:22(4):62-67 [PubMed PMID: 27935882]