Introduction

Anemia is described as a reduction in the proportion of the red blood cells. Anemia is not a diagnosis, but a presentation of an underlying condition. Whether or not a patient becomes symptomatic depends on the etiology of anemia, the acuity of onset, and the presence of other comorbidities, especially the presence of cardiovascular disease. Most patients experience some symptoms related to anemia when the hemoglobin drops below 7.0 g/dL.

Erythropoietin (EPO), which is made in the kidney, is the major stimulator of red blood cell (RBC) production. Tissue hypoxia is the major stimulator of EPO production, and levels of EPO are generally inversely proportional to the hemoglobin concentration. In other words, an individual who is anemic with low hemoglobin has elevated levels of EPO. However, levels of EPO are lower than expected in anemic patients with renal failure. In anemia of chronic disease (AOCD), EPO levels are generally elevated, but not as high as they should be, demonstrating a relative deficiency of EPO.

Normal Hemoglobin (Hgb)-specific laboratory cut-offs will differ slightly, but in general, the normal ranges are as follows:

- 13.5 to 18.0 g/dL in men

- 12.0 to 15.0 g/dL in women

- 11.0 to 16.0 g/dL in children

- Varied in pregnancy depending on the trimester, but generally greater than 10.0 g/dL

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of anemia depends on whether the anemia is hypoproliferative (i.e., corrected reticulocyte count <2%) or hyperproliferative (i.e., corrected reticulocyte count >2%).

Hypoproliferative anemias are further divided by the mean corpuscular volume into microcytic anemia (MCV<80 fl), normocytic anemia (MCV 80-100 fl), and macrocytic anemia (MCV>100 fl).

1) Hypoproliferative Microcytic Anemia (MCV<80 fl)

- Iron deficiency anemia [1]

- Anemia of chronic disease (AOCD)

- Sideroblastic anemia [2] (may be associated with an elevated MCV as well, resulting in a dimorphic cell population)

- Thalassemia

- Lead poisoning

2) Hypoproliferative Normocytic Anemia (MCV 80-100 fL)

- Anemia of chronic disease (AOCD)

- Renal failure

- Aplastic anemia

- Pure red cell aplasia

- Myelofibrosis or myelophthisic processes

- Multiple myeloma

Macrocytic anemia can be caused by either a hypoproliferative disorder, hemolysis, or both. Thus, it is important to calculate the corrected reticulocyte count when evaluating a patient with macrocytic anemia. In hypoproliferative macrocytic anemia, the corrected reticulocyte count is <2%, and the MCV is greater than 100 fl. But, if the reticulocyte count is > 2%, hemolytic anemia should be considered.

3) Hypoproliferative Macrocytic Anemia (MCV>100 fL)

- Alcohol

- Liver disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Folate and Vitamin B12 deficiency [3]

- Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

- Refractory anemia (RA)

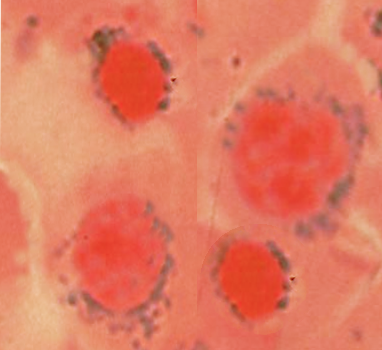

- Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RA-RS)

- Refractory anemia with excess blasts (RA-EB)

- Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation

- Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)

- Drug-induced

- Diuretics

- Chemotherapeutic agents

- Hypoglycemic agents

- Antiretroviral agents

- Antimicrobials

- Anticonvulsants

4) Hemolytic anemiaHemolytic anemia (HA) is divided into extravascular and intravascular causes.

- Extravascular hemolysis: red cells are prematurely removed from the circulation by the liver and spleen. This accounts for a majority of cases of HA

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, thalassemias)

- Enzyemopathies (G6PD deficiency, pyruvate kinase deficiency)

- Membrane defects (hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary elliptocytosis)

- Drug-induced

- Intravascular hemolysis: red cells lyse within the circulation, and is less common.

- PNH

- AIHA

- Transfusion reactions

- MAHA

- DIC

- Infections

- Snake bites/venom

Epidemiology

Anemia is an extremely common disease affecting up to one-third of the global population. In many cases, it is mild and asymptomatic and requires no management.

The prevalence increases with age and is more common in women of reproductive age, pregnant women, and the elderly.

The prevalence is more than 20% of individuals who are older than the age of 85. The incidence of anemia is 50%-60% in the nursing home population. In the elderly, approximately one-third of patients have a nutritional deficiency as the cause of anemia, such as iron, folate, and vitamin B12 deficiency. In another one-third of patients, there is evidence of renal failure or chronic inflammation. [4]

Classically, mild iron-deficiency anemia is seen in women of childbearing age, usually due to poor dietary intake of iron and monthly loss with the menstrual cycles. Anemia is also common in elderly patients, often due to poor nutrition, especially of iron and folic acid. Other at-risk groups include alcoholics, the homeless population, and those experiencing neglect or abuse.

New-onset anemia, especially in those over 55 years of age, needs investigating and should be considered cancer until proven otherwise. This is especially true in men of any age who present with anemia.

Apart from age and sex, the race is also an important determinant of anemia, with the prevalence increasing in the African American population.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of anemia varies greatly depending on the primary cause. For instance, in acute hemorrhagic anemia, it is the restoration of blood volume with intracellular and extracellular fluid that dilutes the remaining red blood cells (RBCs), which results in anemia. A proportionate reduction in both plasma and red cells results in falsely normal hemoglobin and hematocrit.

RBC are produced in the bone marrow and released into circulation. Approximately 1% of RBC are removed from circulation per day. Imbalance in production to removal or destruction of RBC leads to anemia. [5]

The main mechanisms involved in anemia are listed below:

1. Increased RBC destruction

- Blood loss

- Acute- hemorrhage, surgery, trauma, menorrhagia

- Chronic- heavy menstrual bleeding, chronic gastrointestinal blood losses [6] (in the setting of hookworm infestation, ulcers, etc.), urinary losses (BPH, renal carcinoma, schistosomiasis)

- Hemolytic anemia

- Acquired- immune-mediated, infection, microangiopathic, blood transfusion-related, and secondary to hypersplenism

- Hereditary- enzymopathies, disorders of hemoglobin (sickle cell), defects in red blood cell metabolism (G6PD deficiency, pyruvate kinase deficiency), defects in red blood cell membrane production (hereditary spherocytosis and elliptocytosis)

2. Deficient/defective erythropoiesis

- Microcytic

- Normocytic, normochromic

- Macrocytic

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical must be performed.

Some important questions to obtain in a history:

- Obvious bleeding- per rectum or heavy menstrual bleeding, black tarry stools, hemorrhoids

- Thorough dietary history

- Consumption of nonfood substances

- Bulky or fatty stools with foul odor to suggest malabsorption

- Thorough surgical history, with a concentration on abdominal and gastric surgeries

- Family history of hemoglobinopathies, cancer, bleeding disorders

- Careful attention to the medications taken daily

1) Symptoms of anemia

Classically depends on the rate of blood loss. Symptoms usually include the following:

- Weakness

- Tiredness

- Lethargy

- Restless legs

- Shortness of breath, especially on exertion, near syncope

- Chest pain and reduced exercise tolerance- with more severe anemia

- Pica- desire to eat unusual and nondietary substances

- Mild anemia may otherwise be asymptomatic

2) Signs of anemia

- Skin may be cool to touch

- Tachypnea

- Hypotension (orthostatic)

- HEENT:

- Pallor of the conjunctiva

- “Boxcars” or “sausaging” of retinal veins: suggestive of hyperviscosity which can be seen in myelofibrosis

- Jaundice- elevated bilirubin is seen in several hemoglobinopathies, liver diseases and other forms of hemolysis

- Lymphadenopathy: suggestive of lymphoma or leukemia

- Glossitis (inflammation of the tongue) and cheilitis (swollen patches on the corners of the mouth): iron/folate deficiency, alcoholism, pernicious anemia

- Abdominal exam:

- Splenomegaly: hemolysis, lymphoma, leukemia, myelofibrosis

- Hepatomegaly: alcohol, myelofibrosis

- Scar from gastrectomy: decreased absorptive surface with the loss of the terminal ileum leads to vitamin B12 deficiency

- Scar from cholecystectomy: Cholesterol and pigmented gallstones are commonly seen in sickle cell anemia are hereditary spherocytosis

- Cardiovascular:

- Tachycardia

- Systolic flow murmur

- Severe anemia may lead to high output heart failure

- Neurologic exam: Decreased proprioception/vibration: vitamin B12 deficiency

- Skin:

- Pallor of the mucous membranes/nail bed or palmar creases: suggests hemoglobin < 9 mg/dL

- Petechiae: thrombocytopenia, vasculitis

- Dermatitis herpetiformis (in iron deficiency due to malabsorption- Celiac disease)

- Koilonychia (spooning of the nails): iron deficiency

- Rectal and pelvic exam: These examinations are usually overlooked and underperformed in the evaluation of anemia. If a patient has heavy rectal bleeding, one must evaluate for the presence of hemorrhoids or hard masses that suggest neoplasm as causes of bleeding.

Evaluation

Approach to anemia includes identification of the type of anemia: [7][8]

1. Complete blood count (CBC) including differential

2. Calculate the corrected reticulocyte count = percent reticulocytes x (patient's HCT/normal HCT)

For normal HCT, use 45% in men and 40% in women

If result > 2, this suggests hemolysis or acute blood loss, while results < 2 suggests hypoproliferation.

3. After calculating the reticulocyte count, check the MCV.

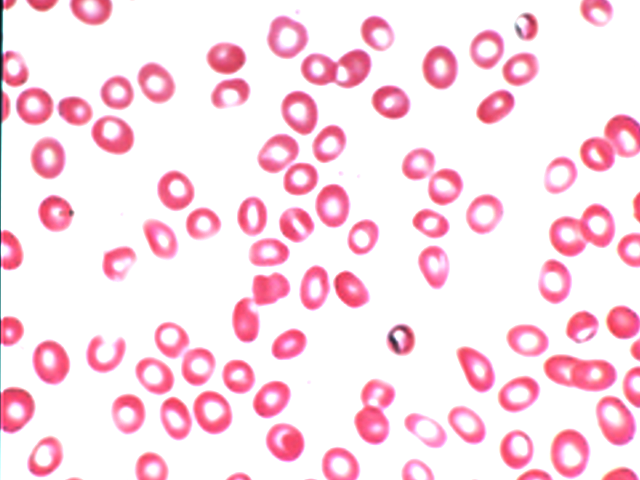

- MCV (<80 fl)

- Iron deficiency- decreased serum iron, percent saturation of iron, with increased total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin levels, and soluble transferrin receptor

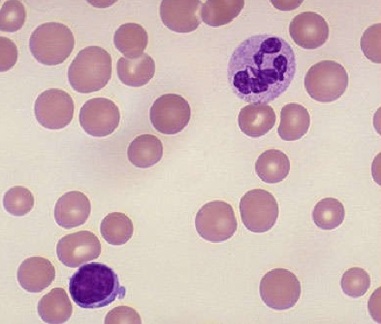

- Lead poisoning- basophilic stippling on the peripheral blood smear, ringed sideroblasts in bone marrow, elevated lead levels

- AOCD- may be normocytic

- Thalassemia- RBC count may be normal/high, low MCV, target cells, and basophilic stippling are on peripheral smear. Alpha thalassemia is differentiated from beta-thalassemia by a normal Hgb electrophoresis in alpha thalassemia. Elevated Hgb A2/HgbF is seen in the beta-thalassemia trait.

- Sideroblastic anemia- elevated serum iron and transferrin with ringed sideroblasts in the bone marrow

- MCV (90-100fl)

- Renal failure: BUN/Creatinine

- Aplastic anemia- ask for drug exposure, check for infections (EBV, hepatitis, CMV, HIV), test for hematologic malignancies and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)

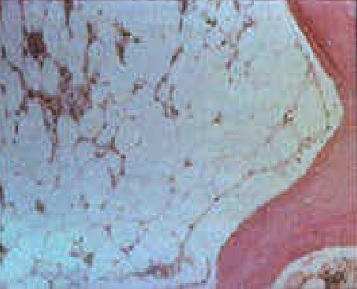

- Myelofibrosis/myelophthisis- check bone marrow biopsy

- Multiple myeloma- serum and urine electrophoresis

- Pure red cell aplasia- test for Parvovirus B19, exclude thymoma

- MCV (>100 fl)

- B12/folate levels- B12 and folate deficiency can be differentiated by an elevated methylmalonic and homocysteine level in B12 deficiency and only an elevated homocysteine level in folate deficiency. Methylmalonic levels are relatively normal.

- MDS- hyposegmented PMNs on peripheral smear, bone marrow biopsy

- Hypothyroidism- TSH, free T4

- Liver disease- check liver function

- Alcohol- assess alcohol intake

- Drugs

Steps to evaluate for hemolytic anemia

1) Confirm the presence of hemolysis- elevated LDH, corrected reticulocyte count >2%, elevated indirect bilirubin and decreased/low haptoglobin

2) Determine extra vs. intravascular hemolysis-

- Extravascular

- Spherocytes present

- Urine hemosiderin negative

- Urine hemoglobin negative

- Intravascular

- Urine hemosiderin elevated

- Urine hemoglobin elevated

3) Examine the peripheral blood smear [9]

- Spherocytes: immune hemolytic anemia (Direct antiglobulin test DAT+) vs. hereditary spherocytosis (DAT-)

- Bite cells: G6PD deficiency

- Target cells: hemoglobinopathy or liver disease

- Schistocytes: TTP/HUS, DIC, prosthetic valve, malignant HTN

- Acanthocytes: liver disease

- Parasitic inclusions: malaria, babesiosis, bartonellosis

4) If spherocytes +, check if DAT is +

- DAT(+): Immune hemolytic anemia (AIHA)

- DAT (-): Hereditary spherocytosis

Other investigations that might be warranted include esophagogastroduodenoscopy for the determination of an upper GI bleed, colonoscopy for the determination of a lower GI bleed, and imaging studies if malignancy, or internal hemorrhage is suspected. If a menstruating woman has heavy vaginal bleeding, evaluate the presence of fibroids with a pelvic ultrasound.

Treatment / Management

Management depends primarily on treating the underlying cause of anemia.

1) Anemia due to acute blood loss- Treat with IV fluids, crossmatched packed red blood cells, oxygen. Always remember to obtain at least two large-bore IV lines for the administration of fluid and blood products. Maintain hemoglobin of > 7 g/dL in a majority of patients. Those with cardiovascular disease require a higher hemoglobin goal of > 8 g/dL.

2) Anemia due to nutritional deficiencies: Oral/IV iron, B12, and folate.

-

Oral supplementation of iron is by far the most common method of iron repletion. The dose of iron administered depends on the patient's age, calculated iron deficit, the rate of correction required, and the ability to tolerate side effects. The most common side effects include metallic taste and gastrointestinal side effects such as constipation and black tarry stools. For such individuals, they are advised to take oral iron every other day, in order to aid in improved GI absorption. The hemoglobin will usually normalize in 6-8 weeks, with an increase in reticulocyte count in just 7-10 days.

-

IV iron may be beneficial in patients requiring a rapid increase in levels. Patients with acute and ongoing blood loss or patients with intolerable side effects are candidates for IV iron.

3) Anemia due to defects in the bone marrow and stem cells: Conditions such as aplastic anemia require bone marrow transplantation.

4) Anemia due to chronic disease: Anemia in the setting of renal failure, responds to erythropoietin. Autoimmune and rheumatological conditions causing anemia require treatment of the underlying disease.

5) Anemia due to increased red blood cell destruction:

- Hemolytic anemia caused by faulty mechanical valves will need replacement.

- Hemolytic anemia due to medications requires the removal of the offending drug.

- Persistent hemolytic anemia requires splenectomy.

- Hemoglobinopathies such as sickle anemia require blood transfusions, exchange transfusions, and even hydroxyurea to decrease the incidence of sickling.

- DIC, which is characterized by uncontrolled coagulation and thrombosis, requires the removal of the offending stimulus. Patients with life-threatening bleeding require the use of antifibrinolytic agents.

Differential Diagnosis

Hemolysis during phlebotomy and significant hemodilution due to large volume fluid resuscitation may lead to a falsely low red cell count.

In acute blood loss from trauma, anemia may not immediately be present on laboratory testing, as the fluid shifts have not had time to occur to normalize the circulating volume, thus diluting the number of red blood cells remaining

Anemia of chronic disease: consider renal failure, underlying malignancies, and autoimmune conditions

Bone marrow infiltration: consider in a patient with weight loss, fatigue.

Macrocytic anemia with B12/folate deficiency: consider in a patient with paresthesias, vegans/vegetarians or in patients with recent gastric bypass surgeries

Hemolytic anemia: consider in all patients with jaundice, dark urine. Always question the recent use of medications.

Acute upper or lower GI bleed: trauma, carcinoma, peptic ulcer disease, use of NSAIDs.

Prognosis

The prognosis for anemia depends on the cause of anemia.

Nutritional replacements of (iron, B12, folate) should begin immediately. In iron deficiency, replacements must continue for at least three months after the normalization of iron levels, in order to restore iron stores. Usually, nutritional deficiencies have a good prognosis if treated early and adequately.

Anemia, due to acute blood loss, if treated and stopped early, has a good prognosis.

Complications

Anemia, if undiagnosed or left untreated for a prolonged period of time can lead to multiorgan failure and can even death.

Pregnant women with anemia can go into premature labor and give birth to babies with low birth weight [10]. Anemia during pregnancy also increases the risk of anemia in the baby and increased blood loss during pregnancy.

Complications are more predominant in the older population due to multiple comorbidities [11]. The cardiovascular system is the most commonly affected in chronic anemia. Myocardial infarction, angina, and high output heart failure are common complications. Other cardiac complications include the development of arrhythmias and cardiac hypertrophy.

Severe iron deficiency is associated with restless leg syndrome and esophageal webs.

Severe anemia from a young age may lead to impaired neurological development in the form of cognitive, mental, and developmental delays. These complications are unlikely to be amenable to medical management.

Consultations

- Gastroenterologist if a gastrointestinal bleed is suspected

- Nephrologist if anemia of chronic disease in the setting of renal failure is suspected

- Hematologist if a bone marrow disorder is suspected

- Gynecologist if intractable menorrhagia is suspected

- Cardiologist if severe anemia leads to angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or arrhythmias

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with nutritional anemia due to iron deficiency should be educated on food which is rich in iron. Foods such as green leafy vegetables, tofu, red meats, raisins, and dates contain a lot of iron. Vitamin C helps to increase dietary iron absorption. Patients must be advised to avoid excess tea or coffee, as these can decrease iron absorption. Patients on oral iron supplementation must be educated that there is an increased risk of constipation and of the risk of passing black tarry stools. Patients must be advised to contact their doctor if there is severe intolerance to oral iron, as they may be candidates for IV iron supplementation.

Vegan and vegetarian patients, who may be deficient in B12 must be advised to consume food fortified with vitamin B12, such as certain plant and soy products. Patients who had gastric sleeve operations and sleeve gastrectomies are at an increased risk of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, due to the loss of absorptive surface at the terminal ileum.

Pearls and Other Issues

Always send blood films in patients with an unclear etiology of anemia.

Start haematinics early (iron, B12, and folate).

Inform patients of the side effects of iron therapy, including constipation and black, tarry stools.

Consider screening for sickle cell and thalassemia in patients with unexplained anemia or with a family history of these diseases.

Vitamin C aids iron absorption, so coadministration of vitamin C with iron, or encouraging the patients to take iron supplements with orange juice, will aid therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anemia is a heterogeneous condition caused by a variety of diseases. Identifying the cause of anemia and treating it appropriately is very crucial in the management of anemia. This requires interprofessional teamwork between the patient, the patient's primary care provider, and consultant physician based on the cause, such as a gastroenterologist, nephrologist, cardiologist, hematologist, or gynecologist. Taking all necessary medications along with lifestyle modifications and frequent follow up with the team of doctors is essential to prevent the development of complications. Pharmacists provide education to patients about compliance and side effects of medication, as well as checking for drug interactions. Nurses assist with the education of patients and arrange followup laboratory evaluations and appointments. Only with collaborative interprofessional care can anemia cases achieve optimal outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Usuki K. [Anemia: From Basic Knowledge to Up-to-Date Treatment. Topic: IV. Hemolytic anemia: Diagnosis and treatment]. Nihon Naika Gakkai zasshi. The Journal of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. 2015 Jul 10:104(7):1389-96 [PubMed PMID: 26513958]

Bottomley SS, Fleming MD. Sideroblastic anemia: diagnosis and management. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2014 Aug:28(4):653-70, v. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.04.008. Epub 2014 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 25064706]

Engebretsen KV, Blom-Høgestøl IK, Hewitt S, Risstad H, Moum B, Kristinsson JA, Mala T. Anemia following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity; a 5-year follow-up study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2018 Aug:53(8):917-922. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1489892. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30231804]

Patel KV. Epidemiology of anemia in older adults. Seminars in hematology. 2008 Oct:45(4):210-7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.06.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18809090]

Badireddy M, Baradhi KM. Chronic Anemia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521224]

Amin SK, Antunes C. Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846221]

Jamwal M, Sharma P, Das R. Laboratory Approach to Hemolytic Anemia. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2020 Jan:87(1):66-74. doi: 10.1007/s12098-019-03119-8. Epub 2019 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 31823208]

Mumford J, Flanagan B, Keber B, Lam L. Hematologic Conditions: Platelet Disorders. FP essentials. 2019 Oct:485():32-43 [PubMed PMID: 31613566]

Rashid A, A 65-year-old man with anemia: diagnosis with peripheral blood smear. Blood research. 2015 Sep [PubMed PMID: 26457277]

O'Farrill-Santoscoy F, O'Farrill-Cadena M, Fragoso-Morales LE. [Evaluation of treatment of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy]. Ginecologia y obstetricia de Mexico. 2013 Jul:81(7):377-81 [PubMed PMID: 23971384]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTriscott JA, Dobbs BM, McKay RM, Babenko O, Triscott E. Prevalence and Types of Anemia and Associations with Functional Decline in Geriatric Inpatients. The Journal of frailty & aging. 2015:4(1):7-12. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2015.35. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27031910]