Introduction

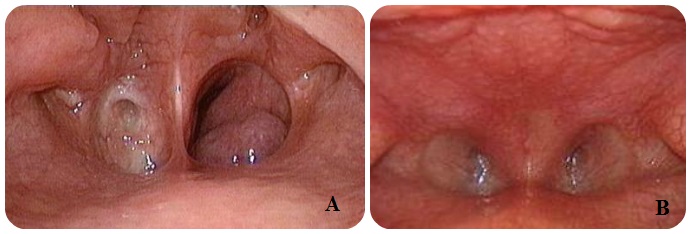

First described in 1755 by Johann Roderer, choanal atresia is a disorder characterized by the congenital absence of the nasal choanae, the paired openings that connect the nasal cavity with the nasopharynx (see Image. Choanal Atresia on Nasal Endoscopy).[1] This condition stems from the failure of nasopharyngeal recanalization during fetal development and can involve soft tissue, bone, or both. Choanal atresia may be complete, lacking communication between the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, or partial, with only choanal stenosis.[2]

Unilateral atresia often presents with unilateral mucopurulent discharge but may not be clinically evident until the child is older if they can breathe through the contralateral side.[3] Bilateral atresia manifests in neonates as respiratory distress immediately after birth due to the inability to breathe, as newborns are obligate nasal breathers. Bilateral choanal atresia is an acute otolaryngologic emergency warranting immediate airway management.[4][5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The choanae develop between the 3rd and 7th embryonic weeks, following the rupture of the vertical epithelial fold between the olfactory groove and the stomodeum, the roof of the primary oral cavity.[7] While the precise mechanisms remain elusive, the following theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of choanal atresia:

- Persistence of the buccopharyngeal membrane: The buccopharyngeal or oropharyngeal membrane develops in early embryogenesis and is well-formed by fetal day 25. This membrane is comprised of endoderm and ectoderm and separates the primordial mouth and pharynx. The buccopharyngeal membrane normally ruptures between the 3rd and 7th fetal weeks, connecting the mouth to the rest of the gut.[8] Incomplete or failed rupture of this membrane may lead to choanal atresia, pharyngeal stenosis, or oral synechiae formation.[9][10] The c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway, which is related to programmed apoptosis, has been implicated in the persistence of the buccopharyngeal membrane.[11]

- Persistence of the nasobuccal membrane of Hochstetter: The early nasal cavity begins with neural crest cell migration from the dorsal neural folds in fetal week 3.[12] Nasal pits subsequently form in weeks 5 and 6 and embed with mesenchyme. The resultant separation is the nasobuccal membrane (of Hochstetter, which ruptures after week 6 to form the primitive nasal cavity with choanae.[13]

- Incomplete resorption of the nasopharyngeal mesoderm: The complex interplay between ectodermal, endodermal, mesenchymal, and neural crest cell-derived structures to develop the normal nasal cavity and nasopharynx takes place over fetal weeks 3 to 11.[14] The normal flow of mesoderm, particularly between weeks 4 and 11, includes deposition and resorption. Failed or incomplete mesoderm resorption may lead to persistent bone or soft tissue within the developing choanae, preventing normal communication between the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx.[15][16]

- Local misdirection of neural crest cell migration: Neural crest cells delaminate from the ectoderm layer in an epithelial-mesenchymal transition early in embryogenesis and migrate throughout the developing embryo.[17] Neural crest cells migrate into the pharyngeal arches in week 4, ultimately forming portions of the bony craniofacial skeleton. Aberrant migration of these cells has been implicated in the formation of bony components in atretic choanae.[18]

Molecular and genetic studies supporting these theories give further insights into the pathogenesis of choanal atresia.[19][20]

Epidemiology

The overall reported incidence of choanal atresia varies. A large series from California, USA reported an incidence of 0.82 per 10,000 live births, but the most often quoted figures range from 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 8,000 live births. The CHARGE Syndrome Foundation has quoted the same range.[21][22][23] Choanal atresia is more often unilateral than bilateral (60% vs. 40%), though some recent studies suggest a nearly 1:1 ratio.[24] Historically, choanal atresia was described as occurring more frequently in female than in male individuals (ratio 2:1), though more recent evidence refutes this predisposition.[25] Currently, the condition is most widely accepted as having an equal sex distribution.[16]

Pathophysiology

Current knowledge of the pathophysiology of neonatal respiration has led to the conclusion that infants are obligate nasal breathers, except when crying.[26] This tendency is due to the newborn's elevated laryngeal position as compared to that of the adult.

When a neonate swallows, the larynx elevates to meet the nasopharynx, creating a seal between the soft palate and the lateral walls of the nasopharynx. During inspiration, the neonate draws the tongue backward, creating a vacuum in the oropharynx that moves the floor of the mouth's soft tissue upward and backward toward the soft palate. During expiration, airway pressure pushes the soft palate forward against the tongue and soft tissue in the mouth, further obstructing the oral airway.[27][28] Thus, infants with bilateral choanal atresia experience asphyxia and severe respiratory distress during quiet breathing when the mouth remains closed, particularly during sleep or feeding. Cyanosis develops but is relieved by crying or gasping, as widely opening the mouth alleviates the obstruction.

Approximately 50% of babies born with choanal atresia have a defined associated syndrome, which may have a known genetic mechanism. Among the most common are the following:

- Abnormal CHD7 gene: Syndrome of coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, mental retardation, genitourinary abnormalities, and ear deformities (CHARGE) [29]

- Mutant FGFR2 gene: Crouzon syndrome [30]

- Deletion in 22q11.2: DiGeorge syndrome [31]

- Aberrant TCOF1 gene: Treacher-Collins syndrome [32]

- Mutant FGFR1 or FGFR2 gene: Pfeiffer syndrome [33]

- No apparent genetic cause: Amniotic band syndrome [34]

History and Physical

Postnatal history and physical examination are critical to diagnosis. The clinical presentation of choanal atresia varies from acute, life-threatening airway obstruction to chronic, recurrent nasal discharge on the affected side, depending on whether the abnormality is unilateral or bilateral.

Infants with bilateral choanal atresia experience acute respiratory distress marked by cyanosis that resolves with crying but returns during rest (paradoxical cyanosis). These symptoms typically appear at birth or shortly after, depending on the severity of the atresia or stenosis. In milder cases, feeding difficulties may serve as the initial indication, with affected infants showing progressive airway obstruction and choking episodes during feeding due to the inability to breathe and feed simultaneously.[35]

Infants with unilateral choanal atresia rarely develop respiratory distress, as one choana remains patent. The condition most commonly presents with purulent nasal discharge and obstruction on the affected side. In some cases, the diagnosis may be delayed until adulthood due to nonspecific symptoms, such as unilateral nasal obstruction, snoring, and recurrent sinusitis.

Choanal atresia often occurs alongside other anomalies, with CHARGE syndrome being the most common. This syndrome is characterized by the presence of coloboma, heart disease, choanal atresia, growth and developmental delays, genital hypoplasia, and ear anomalies. A comprehensive physical examination is essential in patients with choanal atresia, with a low threshold for performing cardiac and renal imaging and an audiogram.[36][37][38]

The hallmark finding on physical examination is nasal obstruction or stenosis. Anterior rhinoscopy should be performed, although persistent rhinorrhoea can make assessing the posterior nasal cavity challenging. Examination is essential to rule out other conditions that can mimic choanal atresia, including severe septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, nasal polyposis, and nasal tumors. Placing a dental mirror beneath each nostril to check for fogging during exhalation can be particularly helpful, especially after using a topical nasal decongestant. Nasal endoscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, as it distinguishes between conditions mimicking choanal atresia and determines the degree of stenosis in cases with partial involvement.

Evaluation

After completing a thorough physical examination and addressing any airway problems, imaging may be used to determine the extent and composition of the atresia. Computed tomography is the preferred modality, as it effectively distinguishes between bony and soft tissue components of the atresia. Magnetic resonance imaging is generally unnecessary unless an encephalocele or another skull base defect is suspected. Routine imaging is often not required for unilateral atresia, though this decision is typically based on the surgeon's preference.[39]

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment for choanal atresia is surgery, focusing on restoring choanal patency, preserving craniofacial development, minimizing invasiveness, and preventing recurrence. Surgical intervention is less urgent for unilateral choanal atresia than for bilateral cases and may be delayed until school age when the anatomy more closely resembles that of adults.[40] Whenever feasible, surgery is ideally postponed until at least 6 months of age, though severe bilateral cases may require earlier intervention. A nasal saline spray can help with nasal toileting while awaiting definitive surgery.

Acute care for infants with bilateral choanal atresia and respiratory distress involves placing an oral airway device, such as a Guedel or other oropharyngeal airway. Alternatively, a McGovern nipple with the end cut off may be used to keep the mouth open. This measure is temporary, as definitive endotracheal intubation is required to stabilize the airway in preparation for urgent surgical repair. Historically, 5 surgical approaches have been described: transpalatal, transeptal, sublabial, transantral, and transnasal.[41](B3)

The transpalatal approach was the most frequently used method until the development of the endoscopic endonasal approach, which is now the standard of care for nearly all cases.[42] Endoscopic techniques offer improved outcomes with fewer complications compared to traditional open procedures. This approach allows direct visualization of the atretic segment, which is then perforated with rigid instruments or drilled out if bone is present. The overlying mucosa is redraped to ensure the patency of the neochoana. Septal mucosal flaps may be used similarly to maintain this patency.[43](B2)

The use of choanal stenting and mitomycin C as adjuncts to prevent restenosis remains controversial due to a lack of strong supporting evidence.[44] More recently, balloon dilatation combined with long-term stenting has been used for membranous atresia, but its long-term effectiveness compared to formal surgical repair is still uncertain.[45]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of choanal atresia includes the following:

- Antrochoanal polyp

- Chordoma

- Deviated nasal septum

- Dislocated nasal septum

- Hematoma

- Isolated piriform aperture stenosis

- Nasal dermoid

- Nasolacrimal duct cyst

- Turbinate hypertrophy

- Tumor

- Encephalocele

A thorough evaluation of these potential conditions helps guide appropriate treatment strategies.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for choanal atresia is very good. However, bilateral cases must be recognized early and definitively treated emergently if respiratory compromise is present. The prognosis of any concurrent underlying syndrome or genetic condition primarily drives the overall outlook for patients. If none are present, normal life expectancy and development are expected.[46]

Complications

Recurrence is the primary complication of choanal stenosis, with 20% to 30% of cases requiring a second surgical intervention at some point. Risk factors for recurrence include bilateral involvement, age younger than 1 year at first repair, and the presence of an underlying syndrome.[47][48] Additional complications common after transnasal endoscopic surgery of any kind include orbital injury, skull base injury, bleeding, and infection.[49] Open transpalatal procedures carry similar risks, with the added potential for oronasal fistula and disruption of maxillary growth.[50]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative pain is managed with oral analgesics. Nasal saline drops are used during the first few weeks to minimize crusting and dryness. Some surgeons may also recommend a steroid-containing topical drop during the first week to reduce granulation tissue formation, especially if bone was removed.[51] Some surgeons prefer the use of postoperative stents. These stents are typically left in place for 2 to 6 weeks before being removed.[52]

Pearls and Other Issues

Choanal atresia must be included in the differential diagnosis in a child with nasal or upper airway obstruction or respiratory distress. Bilateral choanal atresia should be considered in a neonate who becomes cyanotic during feeding and improves with crying. This condition, particularly in its bilateral form, constitutes a medical-surgical emergency requiring prompt treatment. Given the high association of this malformation with various congenital conditions, most notably CHARGE syndrome, evaluating for other inborn anomalies that may complicate the clinical picture is crucial. The endoscopic endonasal technique should be considered the first choice for surgical treatment of choanal atresia, as it provides direct access to the atretic plate, minimizes intraoperative bleeding, shortens hospitalization, and reduces morbidity.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach involving nurses and clinicians is necessary for the safe management of upper airway obstruction or respiratory distress. The team must include choanal atresia in the differential diagnosis. Bilateral choanal atresia should be considered in a neonate who turns cyanotic with feeding and improves with crying. Choanal atresia, especially in its bilateral form, is a medical-surgical emergency that requires timely intervention. Neonatal nurses should alert the team if any signs of this condition are present, and coordination with neonatologists and otolaryngologists is essential. As many of these infants may have CHARGE syndrome, an interprofessional approach to the evaluation is necessary.

For stable infants, the endoscopic endonasal technique should be the first choice for surgical treatment. This approach provides direct access to the atretic plate, reduces intraoperative bleeding, shortens hospitalization, and lowers morbidity.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

FLAKE CG, FERGUSON CF. CONGENITAL CHOANAL ATRESIA IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1964 Jun:73():458-73 [PubMed PMID: 14196687]

Habibullah A, Mogharbel AM, Alghamdi A, Alhazmi A, Alkhatib T, Zawawi F. Characteristics of Choanal Atresia in Patients With Congenital Anomalies: A Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2022 Sep:14(9):e28928. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28928. Epub 2022 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 36111331]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUssher L, David C, Hansen R, Otto A, McClintick S, McIntire K, Sukpraprut-Braaten S. Unilateral Choanal Atresia in a Child With Prolonged Nasal Congestion. Cureus. 2024 Apr:16(4):e57669. doi: 10.7759/cureus.57669. Epub 2024 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 38707148]

Murray S, Luo L, Quimby A, Barrowman N, Vaccani JP, Caulley L. Immediate versus delayed surgery in congenital choanal atresia: A systematic review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Apr:119():47-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.01.001. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30665176]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMeleca JB, Anne S, Hopkins B. Reducing the need for general anesthesia in the repair of choanal atresia with steroid-eluting stents: A case series. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Mar:118():185-187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.01.004. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30639990]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChan J, Ullas G, Narapa Reddy NVS. Completely Endoscopic Approach Using a Skeeter Drill to Treat Bilateral Congenital Choanal Atresia in a 33 Week Born Pre-term Baby. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2018 Dec:70(4):608-610. doi: 10.1007/s12070-018-1406-4. Epub 2018 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 30464926]

Peart LS, Gonzalez J, Bivona S, Latchman K, Torres L, Undiagnosed Diagnosis Network, Tekin M. Bilateral choanal stenosis in auriculocondylar syndrome caused by a PLCB4 variant. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2022 Apr:188(4):1307-1310. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.62634. Epub 2022 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 34995019]

Zaidi A, Dey AC, Sabra O, James J. Bilateral congenital choanal atresia in a preterm neonate - a rare neonatal emergency: A case report and review of literature. Medical journal, Armed Forces India. 2024 Jan-Feb:80(1):115-118. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.09.011. Epub 2021 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 38261804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParekh NM, Bansal SP, Mehta V, Shirsat PM, Prasad P, Desai RS. Persistent Buccopharyngeal Membrane - A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series. The Cleft palate-craniofacial journal : official publication of the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. 2024 Sep:61(9):1509-1525. doi: 10.1177/10556656231175855. Epub 2023 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 37198932]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKwong KM. Current Updates on Choanal Atresia. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2015:3():52. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00052. Epub 2015 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 26106591]

Houssin NS, Bharathan NK, Turner SD, Dickinson AJ. Role of JNK during buccopharyngeal membrane perforation, the last step of embryonic mouth formation. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2017 Feb:246(2):100-115. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24470. Epub 2016 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 28032936]

Ramsden JD, Campisi P, Forte V. Choanal atresia and choanal stenosis. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2009 Apr:42(2):339-52, x. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19328897]

Urbančič J, Vozel D, Battelino S, Boršoš I, Bregant L, Glavan M, Iglič Č, Jenko K, Lanišnik B, Soklič Košak T. Management of Choanal Atresia: National Recommendations with a Comprehensive Literature Review. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Jan 2:10(1):. doi: 10.3390/children10010091. Epub 2023 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 36670642]

Dunham ME, Miller RP. Bilateral choanal atresia associated with malformation of the anterior skull base: embryogenesis and clinical implications. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1992 Nov:101(11):916-9 [PubMed PMID: 1444099]

Teissier N, Kaguelidou F, Couloigner V, François M, Van Den Abbeele T. Predictive factors for success after transnasal endoscopic treatment of choanal atresia. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2008 Jan:134(1):57-61. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18209138]

Samadi DS, Shah UK, Handler SD. Choanal atresia: a twenty-year review of medical comorbidities and surgical outcomes. The Laryngoscope. 2003 Feb:113(2):254-8 [PubMed PMID: 12567078]

Rizzoti K, Lovell-Badge R. SOX3 activity during pharyngeal segmentation is required for craniofacial morphogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England). 2007 Oct:134(19):3437-48 [PubMed PMID: 17728342]

Cordero DR, Brugmann S, Chu Y, Bajpai R, Jame M, Helms JA. Cranial neural crest cells on the move: their roles in craniofacial development. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2011 Feb:155A(2):270-9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33702. Epub 2010 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 21271641]

Rajan R, Tunkel DE. Choanal Atresia and Other Neonatal Nasal Anomalies. Clinics in perinatology. 2018 Dec:45(4):751-767. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.011. Epub 2018 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 30396416]

Kurosaka H. Choanal atresia and stenosis: Development and diseases of the nasal cavity. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Developmental biology. 2019 Jan:8(1):e336. doi: 10.1002/wdev.336. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30320458]

Nemechek AJ, Amedee RG. Choanal atresia. The Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society : official organ of the Louisiana State Medical Society. 1994 Aug:146(8):337-40 [PubMed PMID: 7930863]

Bajin MD, Önay Ö, Günaydın RÖ, Ünal ÖF, Yücel ÖT, Akyol U, Aydın C. Endonasal choanal atresia repair; evaluating the surgical results of 58 cases. The Turkish journal of pediatrics. 2021:63(1):136-140. doi: 10.24953/turkjped.2021.01.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33686836]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlake KD, Davenport SL, Hall BD, Hefner MA, Pagon RA, Williams MS, Lin AE, Graham JM Jr. CHARGE association: an update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clinical pediatrics. 1998 Mar:37(3):159-73 [PubMed PMID: 9545604]

Harris J, Robert E, Källén B. Epidemiology of choanal atresia with special reference to the CHARGE association. Pediatrics. 1997 Mar:99(3):363-7 [PubMed PMID: 9041289]

Freng A. Congenital choanal atresia. Etiology, morphology and diagnosis in 82 cases. Scandinavian journal of plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1978:12(3):261-5 [PubMed PMID: 741215]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBergeson PS, Shaw JC. Are infants really obligatory nasal breathers? Clinical pediatrics. 2001 Oct:40(10):567-9 [PubMed PMID: 11681824]

Trabalon M, Schaal B. It takes a mouth to eat and a nose to breathe: abnormal oral respiration affects neonates' oral competence and systemic adaptation. International journal of pediatrics. 2012:2012():207605. doi: 10.1155/2012/207605. Epub 2012 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 22811731]

Warren DW, Hairfield WM, Seaton D, Morr KE, Smith LR. The relationship between nasal airway size and nasal-oral breathing. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 1988 Apr:93(4):289-93 [PubMed PMID: 3162637]

Hsu P, Ma A, Wilson M, Williams G, Curotta J, Munns CF, Mehr S. CHARGE syndrome: a review. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2014 Jul:50(7):504-11. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12497. Epub 2014 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 24548020]

Azoury SC, Reddy S, Shukla V, Deng CX. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (FGFR2) Mutation Related Syndromic Craniosynostosis. International journal of biological sciences. 2017:13(12):1479-1488. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.22373. Epub 2017 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 29230096]

Bassett AS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Devriendt K, Digilio MC, Goldenberg P, Habel A, Marino B, Oskarsdottir S, Philip N, Sullivan K, Swillen A, Vorstman J, International 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome Consortium. Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011 Aug:159(2):332-9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.039. Epub 2011 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 21570089]

Marszałek-Kruk BA, Wójcicki P, Dowgierd K, Śmigiel R. Treacher Collins Syndrome: Genetics, Clinical Features and Management. Genes. 2021 Sep 9:12(9):. doi: 10.3390/genes12091392. Epub 2021 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 34573374]

Chokdeemboon C, Mahatumarat C, Rojvachiranonda N, Tongkobpetch S, Suphapeetiporn K, Shotelersuk V. FGFR1 and FGFR2 mutations in Pfeiffer syndrome. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2013 Jan:24(1):150-2. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182646454. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23348274]

Cignini P, Giorlandino C, Padula F, Dugo N, Cafà EV, Spata A. Epidemiology and risk factors of amniotic band syndrome, or ADAM sequence. Journal of prenatal medicine. 2012 Oct:6(4):59-63 [PubMed PMID: 23272276]

Abraham ZS, Kahinga AA. Bilateral choanal atresia diagnosed in a 3-month-old female baby: a case report. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2023 Apr:85(4):1227-1230. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000484. Epub 2023 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 37113842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith MM, Ishman SL. Pediatric Nasal Obstruction. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2018 Oct:51(5):971-985. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2018.05.005. Epub 2018 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 30031550]

Zawawi F, McVey MJ, Campisi P. The Pathogenesis of Choanal Atresia. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2018 Aug 1:144(8):758-759. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1246. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29955759]

Mohan S, Fuller JC, Ford SF, Lindsay RW. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of Nasal Airway Obstruction: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2018 Sep 1:20(5):409-418. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0279. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29801120]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceŠebová I, Vyrvová I, Barkociová J. Nasal Cavity CT Imaging Contribution to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Choanal Atresia. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2021 Jan 21:57(2):. doi: 10.3390/medicina57020093. Epub 2021 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 33494264]

Newman JR, Harmon P, Shirley WP, Hill JS, Woolley AL, Wiatrak BJ. Operative management of choanal atresia: a 15-year experience. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2013 Jan:139(1):71-5. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23329094]

Rossi NA, Benavidez M, Pine HS, Daram S, Szeremeta W. Surgical Management of Choanal Atresia: Two Classic Cases and Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2022 Apr:14(4):e24259. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24259. Epub 2022 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 35607544]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEladl HM, Khafagy YW. Endoscopic bilateral congenital choanal atresia repair of 112 cases, evolving concept and technical experience. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Jun:85():40-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.03.011. Epub 2016 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 27240494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang PP, Tang LX, Zhang J, Yang XJ, Zhang W, Han Y, Xiao X, Ni X, Ge WT. Combination of the endoscopic septonasal flap technique and bioabsorbable steroid-eluting stents for repair of congenital choanal atresia in neonates and infants: a retrospective study. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d'oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2021 Aug 12:50(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s40463-021-00535-9. Epub 2021 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 34384505]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBaumann I, Sommerburg O, Amrhein P, Plinkert PK, Koitschev A. [Diagnostics and management of choanal atresia]. HNO. 2018 Apr:66(4):329-338. doi: 10.1007/s00106-018-0492-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29500502]

Riepl R, Scheithauer M, Hoffmann TK, Rotter N. Transnasal endoscopic treatment of bilateral choanal atresia in newborns using balloon dilatation: own results and review of literature. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2014 Mar:78(3):459-64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.017. Epub 2013 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 24445248]

Moreddu E, Rossi ME, Nicollas R, Triglia JM. Prognostic Factors and Management of Patients with Choanal Atresia. The Journal of pediatrics. 2019 Jan:204():234-239.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.074. Epub 2018 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 30291020]

Durmaz A, Tosun F, Yldrm N, Sahan M, Kvrakdal C, Gerek M. Transnasal endoscopic repair of choanal atresia: results of 13 cases and meta-analysis. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2008 Sep:19(5):1270-4. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181843564. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18812850]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFerlito S, Maniaci A, Dragonetti AG, Cocuzza S, Lechien JR, Calvo-Henríquez C, Maza-Solano J, Locatello LG, Caruso S, Nocera F, Achena A, Mevio N, Mantini G, Ormellese G, Placentino A, La Mantia I. Endoscopic Endonasal Repair of Congenital Choanal Atresia: Predictive Factors of Surgical Stability and Healing Outcomes. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Jul 26:19(15):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159084. Epub 2022 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 35897454]

Stankiewicz JA, Lal D, Connor M, Welch K. Complications in endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a 25-year experience. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Dec:121(12):2684-701. doi: 10.1002/lary.21446. Epub 2011 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 22086769]

Chan L, Kitpornchai L, Mackay S. Causative Factors for Complications in Transpalatal Advancement. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2020 Jan:129(1):18-22. doi: 10.1177/0003489419867969. Epub 2019 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 31409097]

Maheshwaran S, Pookamala S, Vijay Pradap R, Rajavel S. Practical Tips for Surgical Management of Bilateral Choanal Atresia. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2023 Apr:75(Suppl 1):768-773. doi: 10.1007/s12070-022-03333-5. Epub 2022 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 37206801]

Alsubaie HM, Almosa WH, Al-Qahtani AS, Margalani O. Choanal Atresia Repair With Stents and Flaps: A Systematic Review Article. Allergy & rhinology (Providence, R.I.). 2021 Jan-Dec:12():21526567211058052. doi: 10.1177/21526567211058052. Epub 2021 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 35173993]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence