Introduction

Groove pancreatitis is a unique clinical condition. It is defined as chronic segmental pancreatitis involving the duodenum and pancreas.[1] The inflammation is seen in the anatomical area between the head of the pancreas, the medial wall of the second part of the duodenum, and the common bile duct.[2] The term cystic dystrophy of the heterotopic pancreas or duodenal dystrophy was first reported by French authors Potet and Duclert in 1970.[3] The term 'Rinnenpankreatitis' was described in 1973 by a German physician, Becker. However, in 1982, Stole et al described groove pancreatitis.[4] It has been used as a broad term and includes para-duodenal pancreatitis, cystic dystrophy of the heterotopic pancreas, periampullary duodenal wall cyst, and pancreatic hamartoma of the duodenum.[5][6] Pathogenesis involves fibrosis in the anatomical region in the para-duodenal tunnel, leading to altered pancreatic secretions and pancreatitis.[7] Stole et al classified grove pancreatitis into 2 forms: pure and segmental.[4] The inflammation in the pure form involves the groove area only. In contrast, in the segmental form, the inflammation involves the groove area with extensive extension into the head of the pancreas.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Alcohol misuse is a significant risk factor for groove pancreatitis.[8] Chronic alcohol use decreases the volume of the pancreas and increases the viscosity of the pancreatic secretions.[9] Alcohol has also been found to reduce the citrate concentration in the pancreatic secretions, causing crystallization in the main pancreatic duct (duct of Wirsung). This acts as a nidus for pancreatic stone formation. Alcohol ingestion also leads to Brunner's gland hyperplasia in the second part of the duodenum. In addition, pancreatic ductal stones can obstruct the dorsal accessory duct (Santorini duct) as it emerges into the minor papilla.[10] Another mechanism in chronic alcoholics is the formation of proteinaceous plugs short of stone formation within the pancreatic ducts. Other anatomical and functional conditions lead to altered pancreatic secretions. The anatomical conditions involve pancreatic divisum, annular pancreas, and ectopic pancreas, and the functional pathologies include duodenal wall thickening.[11] In addition, Solte et al postulated peptic ulcers as a potential causative agent for groove pancreatitis.[12] Other factors include gastric sections, cysts of the pancreatic head, and prior biliary tract pathologies.

Epidemiology

The prevalence has been reported at about 8.9% for the pure form of groove pancreatitis and about 15.5%, for the segmental form of groove pancreatitis, in a study of 123 patients by Stole et al.[4] Groove pancreatitis has been associated with alcohol use disorder.[13] The prevalence is high in males in the fifth decade. It can be seen in females, but the prevalence is low.[14]

Pathophysiology

Groove Pancreatitis is caused by altered pancreatic secretions leading to retained secretions in the pancreatic head, causing inflammation around and involving the duodenum. The dorsal duct (the duct of Santorini) opens at the minor papilla. Due to the inflammation, changes in the duodenum lead to blockage or obstruction of the minor papilla. This leads to secretions being diverted to the main pancreatic duct (the duct of Wirsung) at an acute angle.[15] This diversion leads to incomplete drainage and retention of the secretions in the head of the pancreas. The retention of secretions within the pancreas causes increased intraductal pressure, which leads to the formation of pancreatic fluid collection and leakage of pancreatic secretions into the duodenal groove, leading to an acute inflammatory response.[16] Other factors, such as Brunner's gland hyperplasia, lead to the blockage of pancreatic ductal drainage and potential obstruction with increased inflammation.[17]

Histopathology

Macroscopic Appearance

The inspection of the area around the minor papilla is essential for diagnosis.[7] There is thickening and scarring of the duodenal wall along with trabecular arrangement, often associated with cysts formation.[18] There are 2 pathological subtypes of groove pancreatitis: cystic and solid. The cystic type is characterized by multiple cysts emerging from the mucosa, ranging in size from 1 to 10 cm, leading to para-duodenal wall cysts that simulate intestinal duplication.[7] The solid type is identified by significant thickening of the duodenal wall and smaller cysts, less than 1 cm. Other macroscopic findings include thickened mucosal folds, ulceration, retraction of the duodenal mucosa, and lymph node enlargement in the pancreatic head.[11]

Microscopic Appearance

The duodenal wall shows myeloid cell proliferation in the submucosal muscles of the minor papilla.[18] Other findings include heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the submucosal or muscular layer of the duodenum.[19] The dilated ducts in the myeloid cell proliferation are covered with columnar epithelium, which can erode and become hyper-cellular fibroblast-like tissue resembling a pseudocyst.[20] In addition, the extravasation of mucopurulent material from the ducts can present as giant cell infiltration along with eosinophils. Other common findings are Brunner's gland hyperplasia and neural inflammation into the proliferating islets causing pseudo infiltration.[21]

History and Physical

The most common clinical presentation involves abdominal pain, localized in the upper abdomen, weight loss, postprandial vomiting secondary to duodenal stenosis, and diarrhea.[22] In addition, jaundice is present if the inflammation affects the common bile duct.[23] Kager et al did a study of 335 patients; abdominal pain was reported in 308/335 (92%), vomiting in 105/335 (31%), weight loss in 215/277(78%), jaundice in 32/261 (12%), cholestasis in 73/264 (28%) and steatorrhea in 48/179 (27%).[24]

Evaluation

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory testing and biochemical markers are often nonspecific. Serum pancreatic enzymes (lipase, amylase, and elastase) are mildly elevated, and hepatic enzyme levels are sometimes elevated.[15] A mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase and GGT is also seen, which reflects cholestasis. The bilirubin may be slightly elevated in patients with common bile duct structures. The tumor markers, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen (CA-19-9) levels are usually normal, unlike in patients with pancreatic carcinoma.[25]

Imaging

Abdominal Ultrasound

Ultrasonography usually demonstrates a hyperechoic mass along with duodenal wall thickening.[26] A study by Wronski et al; stated that different findings were observed on the ultrasound depending upon the stage of evolution of pancreatitis.[21] Inflammation is more prominent in the initial stages of the disease. However, as the disease progresses, fibrosis is predominant over inflammation. During the early stages of the disease process, the inflammation causes a hypoechoic bandlike thickening in the pancreaticoduodenal groove, moderate duodenal wall thickening, and heterogenicity of the pancreatic head (see Image. Computed Tomography, Abdomen). In the later stages, hyperechoic thickening of the duodenum is seen. During the later stages, myeloid cell proliferation and fibrosis lead to the characteristic finding of the hyperechoic pancreatic head with anechoic ductal structures.[21]

CT Scan of the Abdomen

CT scan of the abdomen is helpful in the diagnosis and correlates with the histological features of the disease.[27] In the pure subtype, a hypodense laminar mass is seen between the duodenum, near the minor papilla and pancreatic head, corresponding to the scar tissue.[28] There is also delayed contrast uptake due to reduced blood flow in the fibrotic tissue. The scan also shows cysts of varying sizes in the groove or wall of the duodenum or even a multilocular cystic mass.[29] The main pancreatic duct is usually normal.[1] In the segmental form, a hypodense lesion may be observed in the pancreatic head near the wall of the duodenum.[29] In addition, the dilation of the main pancreatic duct is noted in the body and tail of the pancreas.[30] The common bile duct may also narrow in the distal part, with dilation upstream in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree.[2]

ERCP

ERCP is challenging and potentially risky to perform due to the inability to pass the scope secondary to duodenal stenosis.[16] However, if successful, it shows smooth stricturing of the distal common bile duct without any abnormality in the main pancreatic duct or mild pancreatic ductal dilation may be seen.[26] Another finding on the ERCP is an obstruction or irregular stenosis of the duct of Santorini and its branches.[17]

EUS

According to studies, EUS can help determine the disease's exact location and extent. EUS shows the thickening of the second part of the duodenum along with duodenal stenosis, smooth stricturing of the common bile duct, and cysts in the duodenal wall.[22] Other findings include heterogeneous hyperechoic lesions invading the wall of the duodenum, enlargement of the pancreatic head, and pancreatic calcifications or pseudocysts of the duodenal wall.[29] In the segmental form, the main pancreatic duct dilation might be seen.[27]

EUS with Biopsy

If the sampled area shows extensive spindle cells, giant cells, or hyperplasia of Brunner's gland, it can mimic malignancy.[31][32] However, this can be misleading as the findings of giant cells and Brunner's gland hyperplasia are characteristic of groove pancreatitis. In contrast, the fibrotic area does not rule out malignancy as it could be a reaction secondary to inflammatory changes associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.[2]

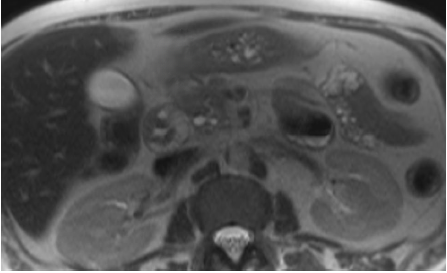

MRI

Multiple studies have shown MRI to be the preferred diagnostic method.[33] MRI shows the presence of a sheet-like mass in the area between the duodenum and the pancreas. The mass is hypo-intense compared to the pancreatic parenchyma on T1-weighted images and is hyperintense on T2-weighted images.[34] Grooves are seen as hypointense areas on T1-weighted imaging, whereas cysts in the duodenum are more appreciated on T2-weighted imaging (see Image. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Abdomen).[2] In the early stages, it is hyperintense secondary to edema, whereas, in later stages, it is hypointense due to fibrotic changes.[35] Cystic lesions are identified in the groove and are more prominent and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.[36] See Image. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Abdomen With Cystic Changes. Also seen are increased thickening and stenosis of the duodenal wall.[34] In the segmental form, the whole pancreas is seen as hypointense on T1 weighted imaging, along with pancreatic atrophy and ductal dilation, corresponding to the loss of cellular components and replacement by fibrotic tissue.[36]

Although several radiological modalities are available, differentiating groove pancreatitis from pancreatic head adenocarcinoma is often challenging. CT and MRI are unreliable due to a large amount of scarring and fibrosis.[37] In 2020, Ishigami et al hypothesized the portal venous phase in CT and MRI might help differentiate groove pancreatitis from pancreatic head carcinoma.[38] The study found more frequent irregular focal enhancement in the portal phase in groove pancreatitis compared with pancreatic head cancer. The study by Kalb et al in 2013 reported a diagnostic accuracy of 87.2% for diagnosing groove pancreatitis utilizing MRI.[39] The study described 3 criteria: focal thickening of the second part of the duodenum, abnormally increased enhancement of the second part of the duodenum, and cystic changes in the area of the dorsal pancreatic duct. According to the report, pancreatic head carcinoma can be ruled out with a negative predictive value of 92.9% if all 3 criteria are present.

Treatment / Management

There are multiple therapeutic options for the management of groove pancreatitis. These include conservative medical management, endoscopic therapy, and surgical interventions. Conservative management includes a healthy, balanced diet, analgesics, pancreatic rest, and abstinence from alcohol and smoking.[2] These could provide short-term relief, but the benefits are not long-lasting.[40] Somatostatin analogs such as octreotide have been used and have shown some positive results.[41] Enteral nutrition is challenging secondary to gastric outlet obstruction or duodenal stenosis, while some patients may require parenteral nutrition.[42] Endoscopic treatment options include dilation of the duodenal and pancreatic ductal stenosis and drainage of the pancreatic duct and symptomatic pseudocysts.[43] Endoscopic interventions are feasible during the early stages of the disease. Still, they might not be helpful in the later stages as scarring leads to duodenal stenosis, which precludes duodenal intubation and access to both the major and the minor papillae. In 2012, Levenick et al reported the placement of a stent in the minor papilla to facilitate pancreatic secretions and provide symptomatic relief from the pain.[44] (B2)

Isayama reported endoscopic treatment of groove pancreatitis by stenting the minor papilla, but the long-term course was unclear.[45] Casetti et al reported poor outcomes from endoscopic therapy.[46] Endoscopic cystoduodenostomy to drain pancreatic fluid collections has been an effective therapy in patients with symptomatic collections.[47] Arvanitakis et al reported a stepwise approach for the treatment of groove pancreatitis. Complete clinical response was achieved in around 80% of the cases using medical and endoscopic treatments.[43] The disadvantage of endoscopic therapy involves failure in about 20% of patients and complications after endoscopic treatment, such as stent migration or stent occlusion.[46] Surgery is the preferred therapeutic option for symptomatic patients refractory to conservative therapy and in patients with a doubtful clinical diagnosis with lesions that are highly suspicious of being malignant. The treatment of choice is pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). Casetti et al reported complete resolution of pain in 76% of the patients.[46] Pancreaticoduodenectomy has effectively managed the main symptoms of groove pancreatitis, pain, and weight loss. In 2007, Rahman et al reported an increase in body weight and relief of chronic abdominal pain in all patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy.[48] Pancreatectomy with duodenal preservation (pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure) has been performed in some instances with satisfactory results.[49][6][5] However, preserving the pylorus and duodenum is not always achievable because of the extensive fibrosis around the duodenal region.[50] Another technique used is duodenal resection with preservation of the pancreas.[49] This has been used in patients with significant duodenal stenosis or who are not candidates for pancreatectomy.[22](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for groove pancreatitis includes the following:

- Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- Duodenal adenocarcinoma

- Periampullary cancers

- Pancreatic groove neuroendocrine tumor

- Cystic dystrophy of the duodenum

- Conventional edematous pancreatitis with involvement of the groove

- Acute pancreatitis

Prognosis

The management is usually conservative, with medical and endoscopic therapy in the initial stages. Conservative management options are a healthy, balanced diet, pain management, pancreatic rest, and abstinence from alcohol and smoking. Usually, these measures provide short-term relief, and occasionally they do provide long-term benefits. Endoscopic therapies are beneficial but could involve a therapeutic failure in about 10 to 20% of patients. The usual definitive therapy is surgery (Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy) in most cases that are refractory to conservative therapy or in which the diagnosis is inconclusive.

Complications

The inflammation associated with groove pancreatitis can lead to several complications. These complications include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, perforation leading to peritonitis, chronic debilitating abdominal pain, duodenal stenosis, distal biliary strictures, chronic pancreatitis, and the potential risk of malignant transformation in the pancreas.[48]

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of groove pancreatitis. They should be made aware of various clinical presentations such as upper quadrant pain, weight loss, postprandial vomiting secondary to duodenal stenosis, and diarrhea. The patients should be counseled to quit drinking alcohol. They should be told to watch their weight and to follow up with their primary physician if they have accompanying abdominal pain and vomiting. Specific education should be provided about the features of jaundice, the inability to tolerate oral intake, and decreased appetite. The treatment options, medical, endoscopic, and surgical therapies, should be discussed with the patients, along with the risks, benefits, and alternatives of all available therapeutic options.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The patients usually present with the symptoms of weight loss, decrease in appetite, and early satiety to the outpatient clinic and with abdominal pain to the emergency. The management involves a multidisciplinary and interprofessional team approach involving primary care providers, specialists, dieticians, psychologists, pain management specialists, radiologists, gastroenterologists, surgeons, and nursing staff. The coordination of care between interprofessional team members leads to improved patient outcomes. The patients might need multiple imaging studies involving CT and MRI scans before establishing the diagnosis. Endoscopic management might include EUS with or without biopsy and ERCP with or without stenting. Surgery is usually the last resort and is useful in refractory cases.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hernandez-Jover D, Pernas JC, Gonzalez-Ceballos S, Lupu I, Monill JM, Pérez C. Pancreatoduodenal junction: review of anatomy and pathologic conditions. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2011 Jul:15(7):1269-81. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1443-8. Epub 2011 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 21312068]

Triantopoulou C, Dervenis C, Giannakou N, Papailiou J, Prassopoulos P. Groove pancreatitis: a diagnostic challenge. European radiology. 2009 Jul:19(7):1736-43. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1332-7. Epub 2009 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 19238393]

Potet F, Duclert N. [Cystic dystrophy on aberrant pancreas of the duodenal wall]. Archives francaises des maladies de l'appareil digestif. 1970 Apr-Mar:59(4):223-38 [PubMed PMID: 5419209]

Stolte M, Weiss W, Volkholz H, Rösch W. A special form of segmental pancreatitis: "groove pancreatitis". Hepato-gastroenterology. 1982 Oct:29(5):198-208 [PubMed PMID: 7173808]

Tezuka K, Makino T, Hirai I, Kimura W. Groove pancreatitis. Digestive surgery. 2010:27(2):149-52. doi: 10.1159/000289099. Epub 2010 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 20551662]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGerman V, Ekmektzoglou KA, Kyriakos N, Patouras P, Kikilas A. Pancreatitis of the gastroduodenal groove: a case report. Case reports in medicine. 2010:2010():329587. doi: 10.1155/2010/329587. Epub 2010 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 20976128]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying "cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas", "para-duodenal wall cyst", and "groove pancreatitis". Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2004 Nov:21(4):247-54 [PubMed PMID: 16273943]

DeSouza K, Nodit L. Groove pancreatitis: a brief review of a diagnostic challenge. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2015 Mar:139(3):417-21. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0597-RS. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25724040]

Arora A, Bansal K, Sureka B. Groove pancreatitis or Paraduodenal pancreatitis: what's in a name? Clinical imaging. 2015 Jul-Aug:39(4):729. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.03.008. Epub 2015 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 25863874]

Shin LK, Jeffrey RB, Pai RK, Raman SP, Fishman EK, Olcott EW. Multidetector CT imaging of the pancreatic groove: differentiating carcinomas from paraduodenal pancreatitis. Clinical imaging. 2016 Nov-Dec:40(6):1246-1252. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.08.004. Epub 2016 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 27636383]

Zamboni G, Capelli P, Scarpa A, Bogina G, Pesci A, Brunello E, Klöppel G. Nonneoplastic mimickers of pancreatic neoplasms. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2009 Mar:133(3):439-53 [PubMed PMID: 19260749]

Ohta T, Nagakawa T, Kobayashi H, Kayahara M, Ueno K, Konishi I, Miyazaki I. Histomorphological study on the minor duodenal papilla. Gastroenterologia Japonica. 1991 Jun:26(3):356-62 [PubMed PMID: 1716233]

Ferreira A, Ramalho M, Herédia V, de Campos R, Marques P. Groove pancreatitis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of radiology case reports. 2010:4(11):9-17. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i11.588. Epub 2010 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 22470697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOza VM, Skeans JM, Muscarella P, Walker JP, Sklaw BC, Cronley KM, El-Dika S, Swanson B, Hinton A, Conwell DL, Krishna SG. Groove Pancreatitis, a Masquerading Yet Distinct Clinicopathological Entity: Analysis of Risk Factors and Differentiation. Pancreas. 2015 Aug:44(6):901-8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25899649]

Shudo R, Obara T, Tanno S, Fujii T, Nishino N, Sagawa M, Ura H, Kohgo Y. Segmental groove pancreatitis accompanied by protein plugs in Santorini's duct. Journal of gastroenterology. 1998 Apr:33(2):289-94 [PubMed PMID: 9605965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMalde DJ, Oliveira-Cunha M, Smith AM. Pancreatic carcinoma masquerading as groove pancreatitis: case report and review of literature. JOP : Journal of the pancreas. 2011 Nov 9:12(6):598-602 [PubMed PMID: 22072250]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSanada Y, Yoshida K, Itoh H, Kunita S, Jinushi K, Matsuura H. Groove pancreatitis associated with true pancreatic cyst. Journal of hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery. 2007:14(4):401-9 [PubMed PMID: 17653641]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlöppel G. Chronic pancreatitis, pseudotumors and other tumor-like lesions. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2007 Feb:20 Suppl 1():S113-31 [PubMed PMID: 17486047]

Shudo R, Yazaki Y, Sakurai S, Uenishi H, Yamada H, Sugawara K, Okamura M, Yamaguchi K, Terayama H, Yamamoto Y. Groove pancreatitis: report of a case and review of the clinical and radiologic features of groove pancreatitis reported in Japan. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2002 Jul:41(7):537-42 [PubMed PMID: 12132521]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAddeo G, Beccani D, Cozzi D, Ferrari R, Lanzetta MM, Paolantonio P, Pradella S, Miele V. Groove pancreatitis: a challenging imaging diagnosis. Gland surgery. 2019 Sep:8(Suppl 3):S178-S187. doi: 10.21037/gs.2019.04.06. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31559185]

Wronski M, Karkocha D, Slodkowski M, Cebulski W, Krasnodebski IW. Sonographic findings in groove pancreatitis. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2011 Jan:30(1):111-5 [PubMed PMID: 21193712]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRebours V, Lévy P, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, Aubert A, Palazzo L, Sauvanet A, Hammel P, Maire F, Ponsot P, Ruszniewski P. Clinical and morphological features of duodenal cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007 Apr:102(4):871-9 [PubMed PMID: 17324133]

Kim JD, Han YS, Choi DL. Characteristic clinical and pathologic features for preoperative diagnosed groove pancreatitis. Journal of the Korean Surgical Society. 2011 May:80(5):342-7. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.80.5.342. Epub 2011 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 22066058]

Kager LM, Lekkerkerker SJ, Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Fockens P, Boermeester MA, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG. Outcomes After Conservative, Endoscopic, and Surgical Treatment of Groove Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2017 Sep:51(8):749-754. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000746. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27875360]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYamaguchi K, Tanaka M. Groove pancreatitis masquerading as pancreatic carcinoma. American journal of surgery. 1992 Mar:163(3):312-6; discussion 317-8 [PubMed PMID: 1539765]

Manzelli A, Petrou A, Lazzaro A, Brennan N, Soonawalla Z, Friend P. Groove pancreatitis. A mini-series report and review of the literature. JOP : Journal of the pancreas. 2011 May 6:12(3):230-3 [PubMed PMID: 21546697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArora A, Rajesh S, Mukund A, Patidar Y, Thapar S, Arora A, Bhatia V. Clinicoradiological appraisal of 'paraduodenal pancreatitis': Pancreatitis outside the pancreas! The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2015 Jul-Sep:25(3):303-14. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.161467. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26288527]

Shanbhogue AK, Fasih N, Surabhi VR, Doherty GP, Shanbhogue DK, Sethi SK. A clinical and radiologic review of uncommon types and causes of pancreatitis. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2009 Jul-Aug:29(4):1003-26. doi: 10.1148/rg.294085748. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19605653]

Dekeyzer S, Traen S, Smeets P. CT features of groove pancreatitis subtypes. JBR-BTR : organe de la Societe royale belge de radiologie (SRBR) = orgaan van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Radiologie (KBVR). 2013 Nov-Dec:96(6):365-8 [PubMed PMID: 24617180]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZaheer A, Haider M, Kawamoto S, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Dual-phase CT findings of groove pancreatitis. European journal of radiology. 2014 Aug:83(8):1337-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.05.019. Epub 2014 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 24935140]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChute DJ, Stelow EB. Fine-needle aspiration features of paraduodenal pancreatitis (groove pancreatitis): a report of three cases. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2012 Dec:40(12):1116-21 [PubMed PMID: 21548125]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrosens LA, Leguit RJ, Vleggaar FP, Veldhuis WB, van Leeuwen MS, Offerhaus GJ. EUS-guided FNA cytology diagnosis of paraduodenal pancreatitis (groove pancreatitis) with numerous giant cells: conservative management allowed by cytological and radiological correlation. Cytopathology : official journal of the British Society for Clinical Cytology. 2015 Apr:26(2):122-5. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12140. Epub 2014 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 24650015]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCastell-Monsalve FJ, Sousa-Martin JM, Carranza-Carranza A. Groove pancreatitis: MRI and pathologic findings. Abdominal imaging. 2008 May-Jun:33(3):342-8 [PubMed PMID: 17624569]

Irie H, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, Hanada K, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, Jimi M, Yamaguchi K, Masuda K. MRI of groove pancreatitis. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1998 Jul-Aug:22(4):651-5 [PubMed PMID: 9676462]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePerez-Johnston R, Sainani NI, Sahani DV. Imaging of chronic pancreatitis (including groove and autoimmune pancreatitis). Radiologic clinics of North America. 2012 May:50(3):447-66. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.03.005. Epub 2012 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 22560691]

Blasbalg R, Baroni RH, Costa DN, Machado MC. MRI features of groove pancreatitis. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2007 Jul:189(1):73-80 [PubMed PMID: 17579155]

Gabata T, Kadoya M, Terayama N, Sanada J, Kobayashi S, Matsui O. Groove pancreatic carcinomas: radiological and pathological findings. European radiology. 2003 Jul:13(7):1679-84 [PubMed PMID: 12835985]

Ishigami K, Tajima T, Nishie A, Kakihara D, Fujita N, Asayama Y, Ushijima Y, Irie H, Nakamura M, Takahata S, Ito T, Honda H. Differential diagnosis of groove pancreatic carcinomas vs. groove pancreatitis: usefulness of the portal venous phase. European journal of radiology. 2010 Jun:74(3):e95-e100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.026. Epub 2009 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 19450943]

Kalb B, Martin DR, Sarmiento JM, Erickson SH, Gober D, Tapper EB, Chen Z, Adsay NV. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: clinical performance of MR imaging in distinguishing from carcinoma. Radiology. 2013 Nov:269(2):475-81 [PubMed PMID: 23847255]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLevenick JM, Gordon SR, Sutton JE, Suriawinata A, Gardner TB. A comprehensive, case-based review of groove pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009 Aug:38(6):e169-75. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ac73f1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19629001]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Parades V, Roulot D, Palazzo L, Chaussade S, Mingaud P, Rautureau J, Coste T. [Treatment with octreotide of stenosing cystic dystrophy on heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall]. Gastroenterologie clinique et biologique. 1996:20(6-7):601-4 [PubMed PMID: 8881576]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePezzilli R, Santini D, Calculli L, Casadei R, Morselli-Labate AM, Imbrogno A, Fabbri D, Taffurelli G, Ricci C, Corinaldesi R. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall is not always associated with chronic pancreatitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2011 Oct 21:17(39):4349-64. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i39.4349. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22110260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArvanitakis M, Rigaux J, Toussaint E, Eisendrath P, Bali MA, Matos C, Demetter P, Loi P, Closset J, Deviere J, Delhaye M. Endotherapy for paraduodenal pancreatitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2014 Jul:46(7):580-7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365719. Epub 2014 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 24839187]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLevenick JM, Sutton JE, Smith KD, Gordon SR, Suriawinata A, Gardner TB. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for the treatment of groove pancreatitis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012 Jul:57(7):1954-8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2214-4. Epub 2012 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 22610883]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIsayama H, Kawabe T, Komatsu Y, Sasahira N, Toda N, Tada M, Nakai Y, Yamamoto N, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Yoshida H, Omata M. Successful treatment for groove pancreatitis by endoscopic drainage via the minor papilla. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2005 Jan:61(1):175-8 [PubMed PMID: 15672084]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCasetti L, Bassi C, Salvia R, Butturini G, Graziani R, Falconi M, Frulloni L, Crippa S, Zamboni G, Pederzoli P. "Paraduodenal" pancreatitis: results of surgery on 58 consecutives patients from a single institution. World journal of surgery. 2009 Dec:33(12):2664-9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0238-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19809849]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePatriti A, Castellani D, Partenzi A, Carlani M, Casciola L. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in paraduodenal pancreatitis: a note of caution for conservative treatments. Updates in surgery. 2012 Dec:64(4):307-9. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0106-3. Epub 2011 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 21866417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRahman SH, Verbeke CS, Gomez D, McMahon MJ, Menon KV. Pancreatico-duodenectomy for complicated groove pancreatitis. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2007:9(3):229-34. doi: 10.1080/13651820701216430. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18333228]

Egorov VI, Vankovich AN, Petrov RV, Starostina NS, Butkevich ATs, Sazhin AV, Stepanova EA. Pancreas-preserving approach to "paraduodenal pancreatitis" treatment: why, when, and how? Experience of treatment of 62 patients with duodenal dystrophy. BioMed research international. 2014:2014():185265. doi: 10.1155/2014/185265. Epub 2014 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 24995273]

Raman SP, Salaria SN, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Groove pancreatitis: spectrum of imaging findings and radiology-pathology correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Jul:201(1):W29-39. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9956. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23789694]