Introduction

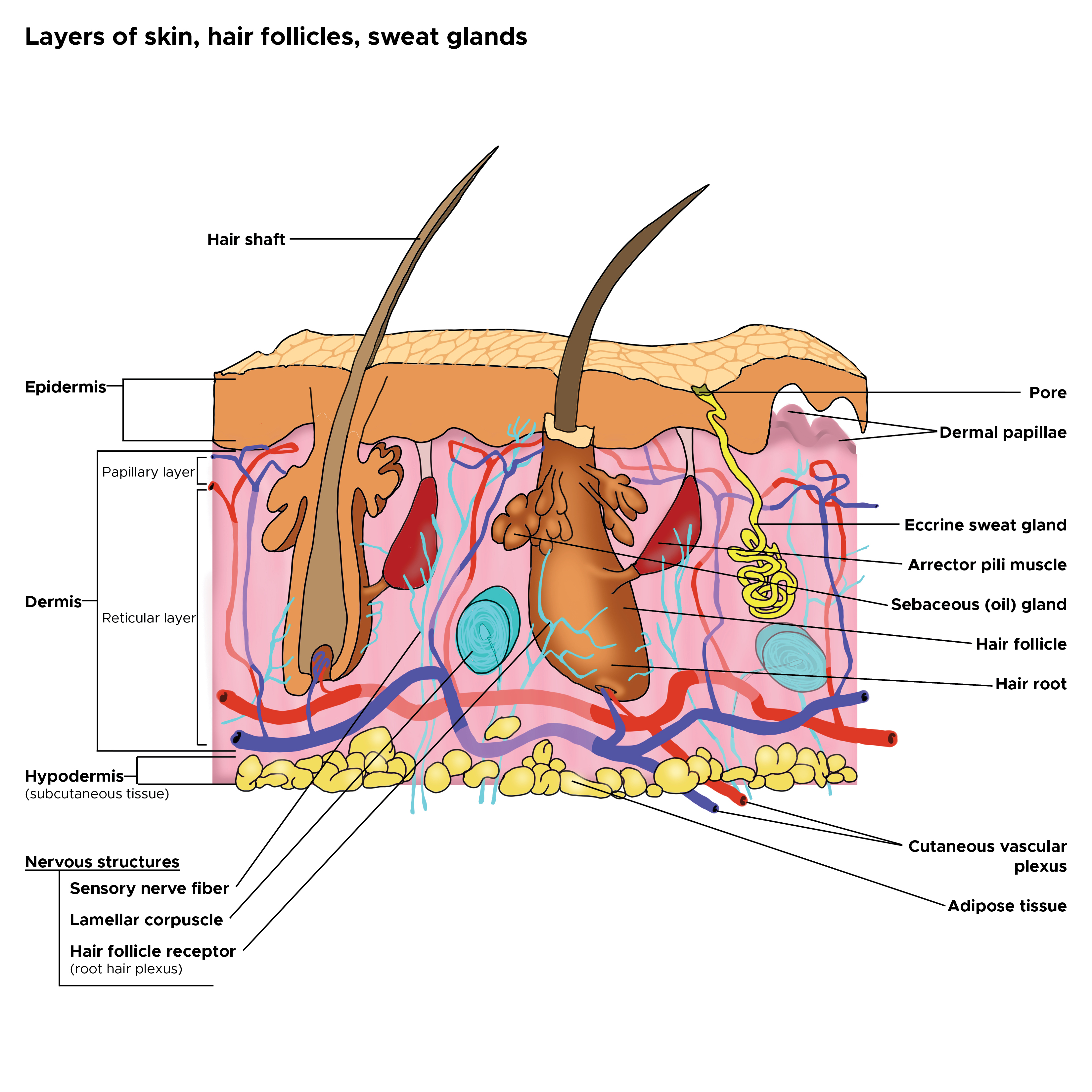

Sweat glands are appendages of the integument. There are eccrine and apocrine sweat glands. They differ in embryology, distribution, and function. Eccrine sweat glands are simple, coiled, tubular glands present throughout the body, most numerously on the soles of the feet. Thin skin covers most of the body and contains sweat glands, hair follicles, hair arrector muscles, and sebaceous glands. Exceptions are the vermillion border of the lips, external ear canal, nail beds, glans penis, clitoris, and labia minora, which do not contain sweat glands. The thick skin covering the palms of hands and soles of feet lacks all skin appendages except sweat glands (see Image. Cross Section, Layers of the Skin).

Apocrine sweat glands, or odoriferous sweat glands, are known for producing malodorous perspiration. They are large, branched glands, mostly confined to the axillary and perineal regions, including the perianal region, labia majora in women, and the scrotum and prepuce in men. Apocrine sweat glands are also present in the nipples and areolar tissue surrounding the nipples.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Eccrine sweat glands serve a thermoregulatory function via evaporative heat loss. When the body's internal temperature rises, sweat glands release water to the skin's surface. There, it quickly evaporates, subsequently cooling the skin and blood beneath.; this is the most effective means of thermoregulation in humans. Eccrine sweat glands also participate in ion and nitrogenous waste excretion. In response to emotional or thermal stimuli, sweat glands can produce at least 500 mL to 750 mL daily.[4][5][6]

Apocrine sweat glands start to function at puberty by stimulating sex hormones. They are associated with hair follicles in the groin and axillary region. The viscous, protein-rich product is initially odorless but may develop an odor after exposure to bacteria. Modified apocrine sweat glands include the wax-producing ceruminous glands of the external auditory meatus, the Moll glands found at the free margins of the eyelids, and the mammary glands of the breast.

Sweat glands play a regenerative role in skin damage. In second-degree cutaneous burns extending into the reticular dermis, regeneration of the epithelium occurs via skin appendages, including hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. The epithelial cells surrounding these appendages produce more epithelial cells that progress to form a new epithelium, a process that can take 1 to 3 weeks.[7]

Embryology

Both eccrine and apocrine sweat glands originate from the epidermis. Eccrine glands begin as epithelial cellular buds that grow into the underlying mesenchyme. The glandular secretory components then form by elongating the gland and coiling the ends. Epithelial attachments of the developing gland create primordial sweat ducts. Finally, the central cells degenerate to form the lumen of the sweat duct. Cells on the periphery of the gland differentiate into secretory and myoepithelial cells. Eccrine sweat glands first appear on the palms and soles during the fourth month of gestation; they become functional soon after birth.

On the other hand, apocrine sweat glands do not function until hormonal stimulation during puberty. Their ducts do not open onto the skin surface because these glands originate from the stratum germinativum of the epidermis. Therefore, down-growth does not produce a duct open to the skin surface. Instead, the ducts open into hair follicles, and sweat is released through the hair opening in the skin. The canals of these apocrine sweat gland ducts enter the hair follicle, which is superficial to the sebaceous gland, resulting in a protein-rich sweat rather than the watery sweat associated with eccrine sweat glands.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Sweat glands and all other skin appendages receive blood supply from cutaneous perforators of underlying source vessels. The perforators may branch directly from the source as septocutaneous or fasciocutaneous perforators or from muscular branches as musculocutaneous perforators. Once these perforators reach the skin, they form extensive dermal and subdermal plexuses networks. Interconnections between these plexuses form via connecting vessels that run perpendicular to the skin's surface, creating a continuous vascular plexus in the skin.

Lymphatic drainage parallels the blood supply, starting with blind-ended lymphatic capillaries in the dermal papillae. These drain into dermal and deep dermal plexuses that eventually coalesce to form larger lymphatic vessels.

Nerves

Eccrine sweat glands receive sympathetic innervation via cholinergic fibers that send impulses in response to changes in core body temperature. The thermoregulatory center of the hypothalamus mediates sympathetic innervation to the sweat glands. A short preganglionic cholinergic fiber originates from the thoracolumbar region of the spinal cord and synapses with the postganglionic neuron via nicotinic acetylcholine. The postganglionic fiber releases acetylcholine, which differs from all other sympathetic postganglionic fibers that release norepinephrine. Cholinergic stimulation of muscarinic receptors induces sweating. Apocrine sweat glands receive adrenergic sympathetic innervation. Because apocrine sweat glands respond to norepinephrine, they are involved in emotional sweating due to stress, fear, pain, and sexual stimulation.

Muscles

Myoepithelial cells are thin, spindle-shaped cells that show epithelium and smooth muscle features. These cells are found in the outer layer of eccrine sweat glands and contract to help expel sweat from the glands.[8]

Clinical Significance

Given the role of sweat glands in thermoregulation, both eccrine and apocrine glands have correlations with various diseases ranging from mild and discomforting to life-threatening. Disorders of sweating can have emotional, social, and professional implications.[9][10][11]

Hyperhidrosis is the excessive excretion of sweat above the quantity needed for thermoregulation. It can be idiopathic or due to other endocrine, neurologic, cardiovascular, neoplastic, infectious disorders, or secondary to intake of medication. Treatment options include topical medications, oral medications, surgical procedures, or botulinum toxin injections. Bromhidrosis is a similar disorder that presents with excessive malodorous perspiration. It can involve either apocrine or eccrine sweat glands; apocrine bromhidrosis tends to develop after puberty, while eccrine bromhidrosis may develop at any age. It is caused by excessive perspiration that secondarily becomes malodorous by the bacterial breakdown. Because poor hygiene most often aggravates bromhidrosis, an effective treatment strategy includes improving personal hygiene. Surgical approaches, antibacterial agents, and antiperspirants are treatment options as well.[12][13][14]

The sweat glands of patients with cystic fibrosis are ineffective at reabsorbing salt, which has significant implications. Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive congenital disease in which the defective cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) normally inhabits the apical membrane of epithelial cells. CFTR is a transmembrane protein that functions as part of a cAMP-regulated chloride ion channel; in normal sweat glands, the ductal epithelium reabsorbs sodium and chloride ions in response to aldosterone so that sweat is hypotonic. In CF patients, the sweat glands fail to reabsorb chloride, affecting sodium reabsorption, resulting in salty sweat and sweat glands' inability to regulate ions. Disruption of the same membrane proteins in the respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelium results in accumulations of thick mucus.[15]

Another autosomal recessive congenital disorder that affects sweat glands is lamellar ichthyosis. Infants with this condition present with persistent scaling skin and impaired hair growth are possible. Impairment of sweat gland development often causes infants to suffer in severely hot weather as they cannot maintain thermoregulation through sweating. General defectiveness of the skin barrier function can also lead to dehydration and increased susceptibility to infections.[16]

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic, inflammatory disease affecting the hair follicles. It is a multifactorial disease where environmental factors and genetics play a significant role. This ailment has classically been associated with the apocrine sweat glands as it manifests after puberty in the apocrine-gland concentrated areas of the body. However, the pathophysiology involves follicular occlusion rather than an apocrine disorder, as previously thought. Patients often present with tender, suppurative subcutaneous nodules and abscesses in the axillae and groin. The lesions can form sinus tracts and extensive scarring.[17]

Hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia is a disease characterized by hypotrichosis (decreased growth of scalp and body hair), hypodontia (congenital absence of teeth), and hypohidrosis. This disease is inherited through an X-linked recessive inheritance mode normally seen in males. The term "hypohidrotic" indicates impairment in the ability to perspire. Patients born with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia have difficulty regulating body temperature and, therefore, must learn to modify their environment to control exposure to heat.[18]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cross Section, Layers of the Skin. This is a cross-section view of the hair follicles, hair roots and shafts, sweat glands, pores, epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The papillary and reticular layers are also included. The eccrine sweat gland is located in the arrector pili muscles, and the sebaceous oil glands are located in the reticular layer.

Contributed by C Rowe

References

Agarwal S, Krishnamurthy K. Histology, Skin. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30726010]

Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: A comprehensive review: Etiology and clinical work-up. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Sep:81(3):657-666. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.071. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30710604]

Fulton EH, Kaley JR, Gardner JM. Skin Adnexal Tumors in Plain Language: A Practical Approach for the General Surgical Pathologist. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2019 Jul:143(7):832-851. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0189-RA. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30638401]

Grubbs H, Nassereddin A, Morrison M. Embryology, Hair. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521215]

Urso B, Lu KB, Khachemoune A. Axillary manifestations of dermatologic diseases: a focused review. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2018 Dec:27(4):185-191 [PubMed PMID: 30564831]

Kabashima K, Honda T, Ginhoux F, Egawa G. The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2019 Jan:19(1):19-30. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0084-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30429578]

Rittié L, Sachs DL, Orringer JS, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Eccrine sweat glands are major contributors to reepithelialization of human wounds. The American journal of pathology. 2013 Jan:182(1):163-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.09.019. Epub 2012 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 23159944]

Balachander N, Masthan KM, Babu NA, Anbazhagan V. Myoepithelial cells in pathology. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2015 Apr:7(Suppl 1):S190-3. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.155898. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26015706]

Gagnon D, Crandall CG. Sweating as a heat loss thermoeffector. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:156():211-232. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63912-7.00013-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30454591]

Murota H, Yamaga K, Ono E, Katayama I. Sweat in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2018 Oct:67(4):455-459. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30082151]

Benzecry V, Grancini A, Guanziroli E, Nazzaro G, Barbareschi M, Marzano AV, Muratori S, Veraldi S. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: a prospective bacteriological study and review of the literature. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2020 Aug:155(4):459-463. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.05875-3. Epub 2018 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 29683279]

Wadhawa S, Agrawal S, Chaudhary M, Sharma S. Hyperhidrosis Prevalence: A Disease Underreported by Patients and Underdiagnosed by Physicians. Indian dermatology online journal. 2019 Nov-Dec:10(6):676-681. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_55_19. Epub 2019 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 31807447]

Wang Y, Sun P, Leng X, Dong Z, Bi M, Chen Z. A new type of surgery for the treatment of bromhidrosis. Medicine. 2019 May:98(22):e15865. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015865. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31145340]

Perera E, Sinclair R. Hyperhidrosis and bromhidrosis -- a guide to assessment and management. Australian family physician. 2013 May:42(5):266-9 [PubMed PMID: 23781522]

Reddy MM, Stutts MJ. Status of fluid and electrolyte absorption in cystic fibrosis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2013 Jan 1:3(1):a009555. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009555. Epub 2013 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 23284077]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChao K, Aleshin M, Goldstein Z, Worswick S, Hogeling M. Lamellar ichthyosis in a female neonate without a collodion membrane. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Feb 15:24(2):. pii: 13030/qt24g7w9t8. Epub 2018 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 29630152]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNapolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, Patruno C, Balato N, Fabbrocini G, Monfrecola G. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2017:10():105-115. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S111019. Epub 2017 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 28458570]

Paramkusam G, Meduri V, Nadendla LK, Shetty N. Hereditary hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: report of a rare case. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2013 Sep:7(9):2074-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5757.3409. Epub 2013 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 24179947]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence