Introduction

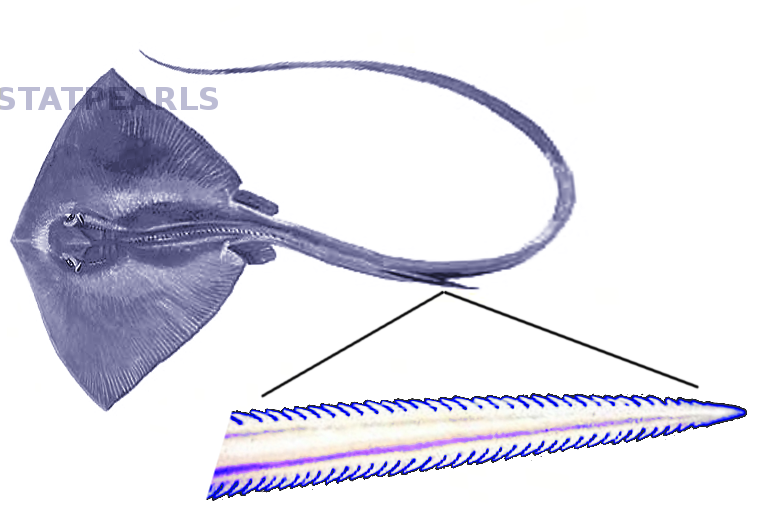

Stingrays are a subset of the cartilaginous fish commonly known as rays. Rays are members of the Chondrichthyes class, which also includes sharks and skates. All rays share a flat body with enlarged pectoral fins that permanently fuse to their heads. The mouth of a stingray is on the ventral side of the animal. The most dangerous aspect of the stingray is the tail due to the spinal blade, also known as its stinger or barb. Rays with longer spines located more distally on their tail represent the greatest danger for sting injuries.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Stingrays can have between one and three spinal blades. The stinger is covered with rows of sharp spines made of vasodentin, a cartilaginous material that can easily cut through the skin. The stingray is unique from other venomous animals in that the venom storage is not in a gland. The venom is stored inside its own secretory cells within the grooves on the undersides of the spine. Freshwater stingrays have more secretory cells that cover a larger area along the blade. Because of this fact, freshwater stingrays have a venom that is more toxic than that of their saltwater relatives. The venom of the stingray has been relatively unstudied but is known to be heat-labile and cardiotoxic.[1][2]

Epidemiology

Stingrays are very common throughout tropical marine waters and freshwaters. There are over 150 species of stingray worldwide, ranging in size from inches to 6.5 feet and in the larger species weighing as much as 800 pounds. Stingrays often feed in or near coral reefs, causing frequent human injuries. In the United States, there are approximately 750 to 2000 stingray injuries reported annually.[3] There are estimated thousands of cases per year in tropical regions with freshwater stingrays that occupy inland rivers.[3] In one retrospective review of 119 cases seen in a California emergency department over 8 years, 80% of stingray victims were male, with an average age of 28 years (range 9 to 68 years old).[4] In a prospective study of freshwater stingray injuries in Brazil, 80% to 90% of the injuries were in men.[5] The most common site of injury is the lower extremities, followed by the upper extremities.[4][5] The majority of stingray injuries have low morbidity, with higher rates of serious injuries and complications in freshwater stings compared to marine stings. In the United States and Indo-Pacific nations, fatalities related to stingray injuries occur one to two times a year, compared to fatality rates up to 8 per year in South American nations related to Amazonian stingrays.[3]

Pathophysiology

Stingrays are not known to be aggressive, nor are they known to act defensively. In fact, the primary defensive action of the stingray is simply to swim away from the area. However, when attacked by a predator or stepped on, the ray will use its tail to puncture and envenomate its potential attacker. Human injuries are most common on the extremities of swimmers and divers and those who accidentally step on a stingray. One way to prevent this is to slide or shuffle through the sand instead of walking.

The mechanism of stingray stings includes both mechanical and venomous injury. First, the barbs pierce through the skin, causing a laceration or puncture wound. In most cases, these wounds are minor, but there are reports of arterial or spinal cord injury related to stingray wounds. The sheath of the barb can also remain in the patient's skin, which may require debridement for removal. The most common venomous effect is severe pain, but the venom can also cause headaches, diaphoresis, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, syncope, muscle cramps, fasciculations, dyspnea, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, and seizures.[4][6]

History and Physical

Patients will present with a puncture wound or laceration and report pain out of proportion to the wound. They will often have a known exposure to a stingray or may have a wound on their foot and report that they stepped on something in the ocean. The onset of severe pain is usually immediate. It reaches maximum intensity within 30 to 90 minutes and can last for up to 48 hours.[6] The site of the wound may have evidence of edema and discoloration. In delayed presentations, there may be evidence of local necrosis. Patients may also report systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, lightheadedness, syncope, shortness of breath, headache, abdominal pain, vertigo, or seizures.[3]

Evaluation

The wound should be evaluated using standard procedures, including irrigation of the wound. Plain films may be obtained to evaluate for foreign bodies at the discretion of the provider. Stingray barbs are radioopaque and are visible on plain films. There is not currently a recommended standard for obtaining radiographs in stingray injuries. However, in one retrospective review, 57% of patients had radiographic imaging. Foreign body identification was found in only 2 cases of 119 (and only definitively in one case; there was a possible barb in the other case).[4]

If the patient presents with an injury to the chest or abdomen or severe systemic symptoms, consider an electrocardiogram (EKG), cardiac monitoring, lab work, and chest radiography. If there is a concern for severe systemic illness, including cardiogenic shock, the patient should be transferred to a facility with ICU capabilities, and a medical toxicology consult may be obtained.

Treatment / Management

The standard treatment for stingray injuries is hot water immersion.[4][6][7] Stingray venom is heat-labile and can be inactivated by heat. Water should be heated to a temperature that will not result in burns, and the temperature should be tested on a non-affected extremity, as the patient may have impaired sensation on the injured extremity. Hot water immersion should be initiated as soon as possible, ideally in the field by lifeguards or paramedics. A small prospective study found that hot water immersion alone resulted in statistically significant pain reduction.[7] Another retrospective study found that hot water immersion alone provided effective pain relief in 9 out of 10 patients. Oral NSAIDs or opioids were used concurrently with hot water immersion in the other 10% of patients. Only 2% of patients required additional pain control at discharge.[4] In patients with freshwater stings in Brazil, hot water immersion was found to help reduce pain but did not decrease rates of skin necrosis.[5](B3)

In addition to hot water immersion, standard wound care techniques should be applied. Irrigate the wound. If there is suspicion for a retained foreign body, obtain radiographs, explore the injury and remove any foreign bodies as they may result in delayed healing and wound necrosis. If the wound is small, it should be left to close by secondary intention or delayed primary closure, due to the risks of infection. Tetanus status should be inquired about and tetanus immunizations updated as necessary. If there is evidence of necrosis, the wound should be debrided.[3] (B3)

There is not a clear consensus on whether antibiotic prophylaxis should be given with some experts arguing that most injuries are minor and prophylaxis should only be given for deep penetrating wounds, wounds complicated by a foreign body, or patients who are immunocompromised. However, in a retrospective review, 70% of patients were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on initial presentation, and only one patient returned with possible early wound infection. Of the 30% of patients not prescribed antimicrobial prophylaxis, 17% returned with signs of wound infection.[4] Antibiotic prophylaxis, therefore, seems prudent, and coverage should include gram-negative species, including Vibrio, as well as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

- Laceration

- Cellulitis

- Necrotizing fasciitis

- Sea urchin

- Lionfish

- Jellyfish

- Coral

- Sea anemone

- Shark bite

- Octopus bite

- Alligator or crocodile attack

- Ciguatera

- Scombroid

- Pufferfish tetrodotoxin

- Shellfish toxin

Prognosis

Stingray injuries, whether through puncture, laceration, or envenomation, usually have a good prognosis. It is important to instruct patients to look for signs of infection after discharge. While it is possible to develop further complications such as infection, most patients will have a significantly decreased amount of pain in one to two days after the incident. Necrosis following marine envenomations was rarely reported in the United States but reported at high rates after freshwater stings in Brazil. A study of 84 freshwater stings in Brazil reported a rate of ulcers and necrosis in 90.4% of cases. The ulcers lasted approximately 3 months and often resulted in scars.[5]

Systemic toxicity or death related to stingray stings is rare and associated with stings resulting in penetrating trauma to the abdomen, chest, or neck resulting in a cardiac laceration, cardiac tamponade, pneumothorax, airway compromise, or hemorrhagic shock. There are cases of delayed fatality secondary to septic shock, osteomyelitis, gangrene, and wound botulism from an infected wound.[3]

Complications

The most common complication of stingray sting is wound infection or necrosis. There are significantly higher rates of skin necrosis associated with freshwater stingray injuries.[5] There are case reports of necrotizing fasciitis following stingray injury.[8]

Consultations

For patients with severe toxic effects, including systemic illness, cardiogenic shock, syncope, shortness of breath, or seizures, a medical toxicology consult may be obtained. The local Poison Control Center may also be a useful consult for these patients.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Stingrays are generally docile animals and are not known for actively attacking humans unless threatened. Stingray injuries can be prevented by encouraging swimmers, divers, and beach-goers to avoid provoking stingrays. Most injuries occur due to accidentally stepping on a ray. This can be prevented by shuffling through the sand without lifting the feet or using a stick or pole to poke the sand ahead of placing the feet. Divers should avoid swimming too close to the seafloor. A fisher who accidentally catches a stingray should not attempt to disentangle it from a net or line.[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach to managing stingray injuries includes proper training of local medics and lifeguards. Many patients with minor stingray injuries do not present to healthcare facilities and may be managed in the field setting by these first responders. In a review of 153 stingray cases reported to Texas poison centers, 61% were not managed in healthcare facilities.[9] First-responders should be trained to immerse stingray wounds in hot water. They should also require training to transfer the patient to a medical facility for wounds with ongoing bleeding, deep penetration, evidence of systemic toxicity, ongoing pain, or patients with comorbid medical conditions. Within the emergency department setting, nurses and technicians are integral in ensuring that the patient has continuous hot water immersion for 30 to 90 minutes. Emergency clinicians should promptly manage any severe effects of the toxin or wound. Medical toxicology may be consulted for severe effects as well.

Media

References

O'Connell C, Myatt T, Clark RF, Coffey C, Nguyen BJ. Stingray Envenomation. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Feb:56(2):230-231. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.11.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30738566]

Sachett JAG, Sampaio VS, Silva IM, Shibuya A, Vale FF, Costa FP, Pardal PPO, Lacerda MVG, Monteiro WM. Delayed healthcare and secondary infections following freshwater stingray injuries: risk factors for a poorly understood health issue in the Amazon. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2018 Sep-Oct:51(5):651-659. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0356-2017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30304272]

Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. Journal of travel medicine. 2008 Mar-Apr:15(2):102-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00177.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18346243]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, Ly BT, Davis DP. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2007 Jul:33(1):33-7 [PubMed PMID: 17630073]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHaddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, de Luna Marques FP, Barbaro KC. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinic and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2004 Mar 1:43(3):287-94 [PubMed PMID: 15033327]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeyer PK. Stingray injuries. Wilderness & environmental medicine. 1997 Feb:8(1):24-8 [PubMed PMID: 11990133]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMyatt T, Nguyen BJ, Clark RF, Coffey CH, O'Connell CW. A Prospective Study of Stingray Injury and Envenomation Outcomes. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Aug:55(2):213-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.04.035. Epub 2018 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 29803633]

Ho PL, Tang WM, Lo KS, Yuen KY. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Vibrio alginolyticus following an injury inflicted by a stingray. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 1998:30(2):192-3 [PubMed PMID: 9730311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceForrester MB. Pattern of stingray injuries reported to Texas poison centers from 1998 to 2004. Human & experimental toxicology. 2005 Dec:24(12):639-42 [PubMed PMID: 16408617]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence