Introduction

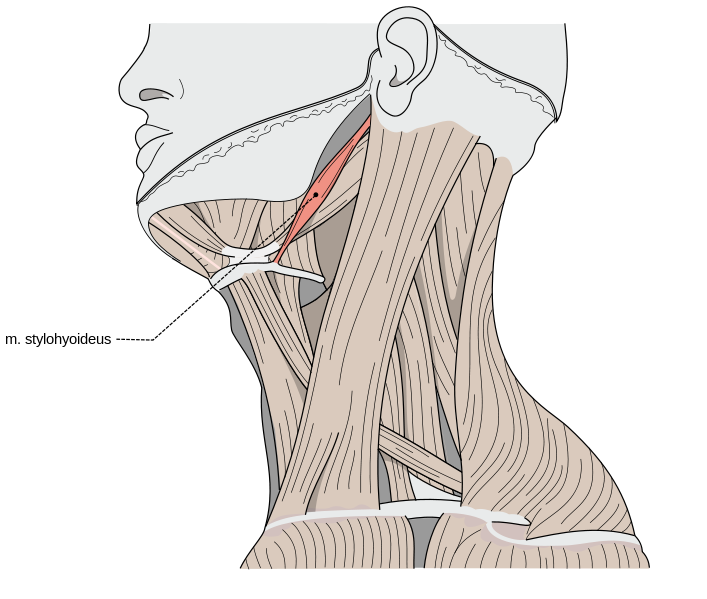

The styloid process is a cylindrical, slender, needle-like projection of varying lengths averaging 2 to 3 cm (see Image. Medial Aspect of Jaw Anatomy). The styloid process projects from the inferior part of the petrous temporal bone and offers attachment to the stylohyoid ligament and the stylohyoid, stylopharyngeus, and styloglossus muscles (see Image. Stylohyoid Muscle). Through these structures, the styloid process facilitates the movement of the tongue, pharynx, larynx, hyoid bone, and mandible. Significant vessels and nerves surround the styloid process. The internal jugular vein, internal carotid artery, glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), vagus nerve (CN X), and accessory nerve (CN XI) lie medial to the styloid process. The occipital artery and hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) run along its lateral side. Originating as a part of Reichert's cartilage forming from the second pharyngeal arch, it undergoes endochondral ossification in the late stages of pregnancy through the first decade of life. The structure shows variations in length, angulation, and other morphological features between individuals. Although these physiological differences are often found incidentally, some patients might develop a constellation of symptoms known as Eagle syndrome. The symptomatology of Eagle syndrome occurs secondary to irritation or compression of surrounding structures from an abnormal styloid process.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

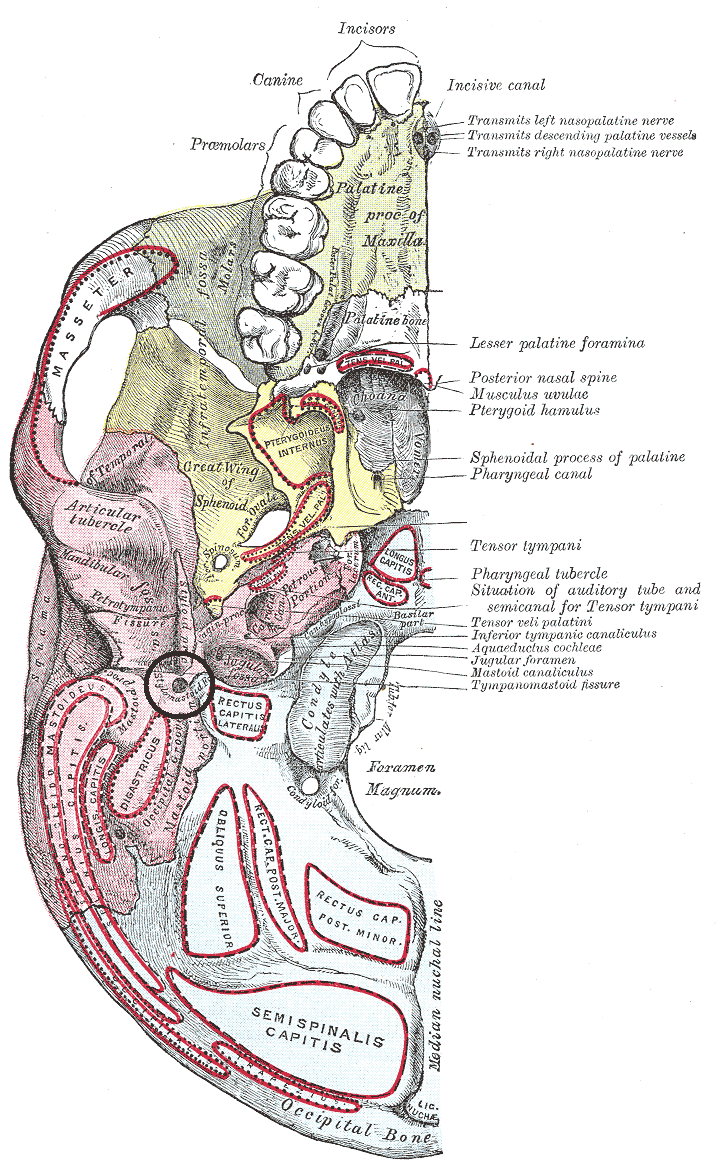

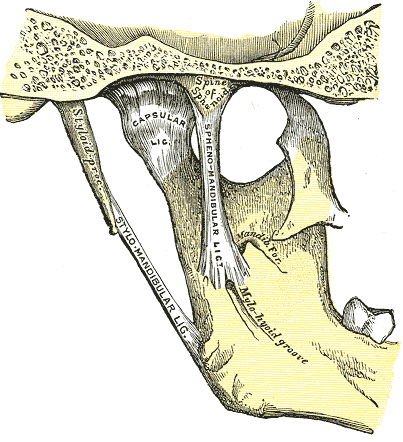

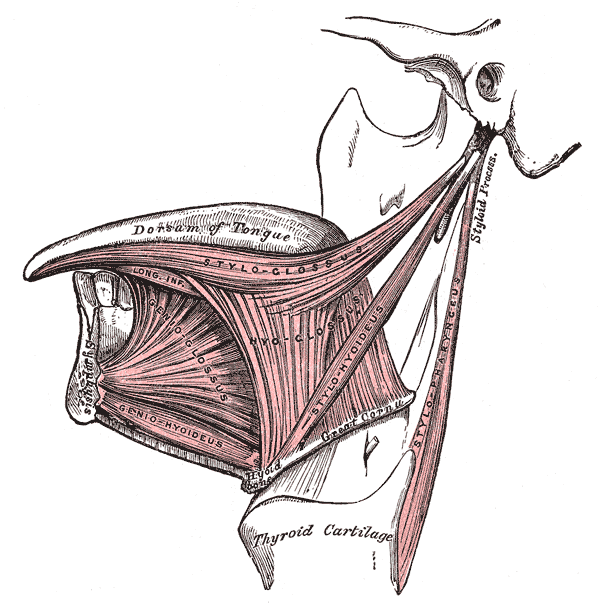

The cylindrical and needle-like structure has a thickness that gradually tapers, forming the apex of the styloid process. The process length varies between individuals, with an average length of 2 to 3 cm.[1] Although the process most commonly follows straight projection, it can vary and is curved.[2] The styloid process projects from the inferior portion of the petrous temporal bone, lying inferior and anterior to the external auditory meatus, anteromedial to the mastoid process, and anterior to the stylomastoid foramen (see Image. Stylomastoid Foramen). It comprises 2 segments: a proximal component and a distal component. The proximal portion consists of the base of the process, which is contained within the vaginal process of the tympanic portion of the temporal bone. The distal component consists of the shaft and is the origin of 3 muscles: the stylohyoid, stylopharyngeus, and styloglossus (see Image. The Mouth, Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue). The styloid process apex is also the origin of 2 ligaments: the stylohyoid ligament, which attaches to the lesser cornu of the hyoid, and the stylomandibular ligament, which attaches to the ramus of the mandible. Both ligaments facilitate the movement of the tongue, pharynx, larynx, hyoid bone, and mandible.[3][4]

Embryology

The styloid process originates as a part of Reichert's cartilage, which forms from the second pharyngeal arch during embryological development [5]. Reichert's cartilage is divided into 4 parts: the tympanohyal part, the stylohyal part, the ceratohyal part, and the hypohyal part. The tympanohyal part develops antenatally, attaches to the petrous portion of the temporal bone, and gives rise to the base of the styloid process, which is ensheathed by the vaginal process of the tympanic part. The stylohyal part appears post-natally, giving rise to the shaft of the styloid process and the proximal portion of the stylohyoid ligament. The stylohyal part might unite with the tympanohyal after puberty; sometimes, they never do. The ceratohyal and its fibrous sheath regress, giving rise to the stylohyoid ligament. The hypohyal part gives rise to the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone.[4][6] The styloid process undergoes endochondral ossification that begins at the final stages of pregnancy and is carried on over the first 8 years of life. However, the pattern of ossification and time to completely ossify has been shown to vary greatly.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Several important vessels lie in the vicinity of the styloid process. Vessels on the medial aspect of the styloid process are the internal jugular vein and the external carotid artery, its branches, the lingual artery, the facial artery, the superficial temporal artery, and the maxillary artery. Along the lateral border of the styloid process, the external carotid artery and 1 of its branches, the occipital artery, are found.[3][4]

Nerves

Various nerves surround the styloid process. On the medial aspect, particularly surrounding the internal jugular vein, the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), the vagus nerve (CN X), and the accessory nerve (CN XI) are located. Lateral to the styloid process are the facial nerve (CN VII) and the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII). The facial nerve exits the skull from the stylomastoid foramen, which is directly posterior to the styloid process; however, it passes lateral to the process as it pierces through the parotid gland before splitting into its subsequent branches (See Image. The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, Posterior).[3][4]

Muscles

The styloid process originates from 3 muscles: the styloglossus, stylohyoid, and stylopharyngeus. The styloglossus receives innervation from CN XII, attaches to the apex of the tongue, and draws up the sides of the tongue to form a conduit that facilitates swallowing.[7] Innervation of the stylohyoid is by CN VII; it attaches to the greater cornu of the hyoid bone with its distal tendon perforated by the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle and elevates the hyoid bone during swallowing. CN IX supplies the stylopharyngeus muscle, attaches to the thyroid cartilage, and elevates the larynx and elevation and dilation of the pharynx during swallowing.[8][9] Moreover, the superior constrictor muscle and the pharyngobasilar fascia neighbor the tonsillar fossa on the medial aspect of the styloid process.

Physiologic Variants

The length of the styloid process is inconsistent across all individuals, with studies reporting average lengths anywhere from 1.52 cm to 8 cm.[10][11] The length of the left and right styloid processes might also differ within the same individual.[12] Although the length of the styloid process might vary from person to person, a length of more than 3 cm is considered elongated.[6] The prevalence of an elongated styloid process is estimated at around 4% of the general population. However, variances between populations, such as rural Indian populations, show a much higher prevalence. An elongated styloid process is more commonly seen in women than men.[4] The ossification and fusion of the styloid process also show variance. As mentioned, the stylohyal part might unite with the tympanohyal after puberty. If the stylohyal part successfully fuses with the tympanohyal part and the stylohyal aspect ossifies, it results in a long styloid process. However, if the stylohyal part fails to ossify, it produces a short styloid process.

Multiple theories have been proposed, such as the etiology responsible for the variance in ossification and elongation of the styloid process. The first theory is the "theory of reactive hyperplasia," which proposes that the styloid process reacts and proliferates after pharyngeal trauma, causing elongation. The second theory is the "theory of reactive metaplasia," which is similar to the first theory in trauma being the triggering factor. However, the second theory suggests that the stylohyoid ligament is the structure responsible for abnormal ossification as it undergoes metaplasia and partial ossification. The third theory is the "theory of anatomic variance," which suggests that the ossification of the styloid process and the stylohyoid ligament is a normal process representing an anatomical variation resulting in the elongation of the styloid process. An additional and fourth theory is that the elongated styloid process is due to retained embryologic tissue from Reichert's cartilage.[13] Although these theories explain the differences in the styloid process, a consensus has not been established.[14][15]

Surgical Considerations

The styloid process serves an essential function as an anatomical divider of the parapharyngeal space (PPS). The tensor-vascular-styloid fascia provides the division into distinct compartments.[16] This fascia runs from the styloid process to the tensor veli palatini muscle. The PPS is divided into the prestyloid (anterolateral) and retrostyloid (posteromedial) compartments to facilitate the differential diagnoses of PPS lesions. The prestyloid compartment contains fat, a portion of the retromandibular parotid gland, and lymph nodes. The retrostyloid region contains the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, CN IX-XII, a segment of the sympathetic chain, and lymph nodes.[16] However, This PPS compartmentalization method has been proposed not to offer the best surgical approach.[17]

Clinical Significance

Clinical Presentation

As mentioned, approximately 4% of the general population has an elongated styloid process. Although the majority of these individuals are asymptomatic, a small percentage of those with an elongated styloid process show symptoms and can present with 1 of 2 types of Eagle syndrome.[18][13][18] The first type, classic Eagle syndrome or stylohyoid syndrome, presents as a sharp pain in the neck or the ear that extends to the maxilla, face, and oral cavity. The pain might appear exaggerated with the head rotation, chewing, swallowing, tongue extension, or yawning. It might also be associated with a foreign body sensation in the pharynx, tinnitus, or vertigo. Additionally, a mass might be palpable in the tonsillar fossa. Symptoms of classic Eagle syndrome are usually unilateral but could rarely present bilaterally.[19] These symptoms occur due to the irritation or possible entrapment of the nearby cranial nerves (CN V, VII, IX, or X). It has been commonly observed that classic Eagle syndrome presents post-tonsillectomy or other pharyngeal surgery. The irritation or entrapment that occurs may be secondary to the formation of local granular cells.[4][20]

The second type of Eagle syndrome is stylocarotid artery syndrome, when the styloid process impinges upon the internal or external carotid artery and the nerve plexus accompanying them. It presents as pharyngeal pain, eye pain, or parietal cephalgia, resembling a migraine or a cluster headache. Internal carotid artery compression might present with internal carotid vascular insufficiency symptoms, such as weakness, visual changes, or syncope exacerbated with head movement. The elongated styloid process might also pose the risk of carotid artery dissection, leading to a transient ischemic attack or stroke.[4][19][21]

Studies analyzing the possible correlation between styloid process length and symptom severity have been inconclusive.[22] However, correlations have been proposed between the angulation, length of the styloid process, and overall development of Eagle syndrome. If the styloid process deviates laterally, it can impinge upon the external carotid artery and its branches. If the styloid process deviates posteriorly, it may impinge upon CN IX, CN X, CN XI, and CN XII between it and the transverse process of the atlas. Moreover, if the styloid process deviates medially or anteriorly, it may irritate the tonsillar fossa and its important structures.[23]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Eagle syndrome depends on the patient's clinical presentation, radiological investigation, and lidocaine infiltration test.[4] The clinical image of Eagle syndrome is not specific and may mimic several other diagnoses. A palpable mass in the tonsillar fossa might allow the clinician to narrow their differential; however, it is not always present in symptomatic Eagle syndrome.[24] For radiological investigations, lateral head and neck X-rays can identify the elongated styloid process, but bilateral processes may overlap and obfuscate the diagnosis. A Towne radiograph, which is an anterior-posterior skull axis view, can be utilized to assess the styloid process's medial or lateral deviation. Computed tomography (CT) allows for the evaluation of length and angulation of the styloid process. A 3D-CT is considered the gold standard of radiological diagnosis and provides the best supplement to a plain X-ray. CT angiography is recommended in stylocarotid syndrome to assess blood flow dynamics.[25][26] The lidocaine infiltration test can be confirmatory for symptomatic patients. After administering 1 ml of 2% lidocaine to the area surrounding the palpable styloid process, if the patient's symptoms are relieved by the anesthetic, the test is considered positive and establishes the diagnosis of Eagle syndrome.[27]

Management

Management of Eagle syndrome can be conservative or surgical, depending on severity. However, initial conservative management is recommended.[28] Conservative management consists of steroid or long-acting anesthetic injections at the inferior portion of the tonsillar fossa or the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone for symptomatic relief.[4] Surgical management can be through an extra-oral transcervical or intra-oral transpharyngeal approach.[29] The extra-oral transcervical approach allows for better visualization but is considered a more complex and time-consuming approach that leaves a visible scar and possible transient weakness in the marginal mandibular nerve.[30] The intra-oral approach provides a shorter operative time with the possibility of using a local anesthetic; however, poorer visualization poses a risk to the major vessels of the neck with an increased risk of bacterial contamination.[29] External manipulation and fracturing of the elongated styloid process under local anesthetic has been proposed but has shown unsatisfactory long-term results.[31]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Jaw Anatomy, Medial Aspect. Jaw anatomy includes the mandible, capsular ligament, spine of the sphenoid, styloid process, stylomandibular ligament, mandible foramen, and mylohyoid groove.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth, Extrinsic Muscles of the Tongue. Left side, dorsum of tongue, styloglossus, hyoglossus, genioglossus, geniohyoideus, stylopharyngeus, and thyroid cartilage.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

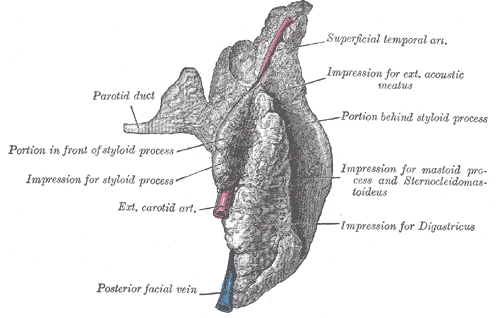

The Mouth, Right Parotid Gland, Posterior. Posterior and deep aspects, parotid duct, styloid process, exterior carotid artery, facial vein, and superficial temporal artery.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Glogoff MR, Baum SM, Cheifetz I. Diagnosis and treatment of Eagle's syndrome. Journal of oral surgery (American Dental Association : 1965). 1981 Dec:39(12):941-4 [PubMed PMID: 6948095]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDas S, Suhaimi FH, Othman F, Latiff AA. Anomalous styloid process and its clinical implications. Bratislavske lekarske listy. 2008:109(1):31-3 [PubMed PMID: 18447260]

Vadgaonkar R, Murlimanju BV, Prabhu LV, Rai R, Pai MM, Tonse M, Jiji PJ. Morphological study of styloid process of the temporal bone and its clinical implications. Anatomy & cell biology. 2015 Sep:48(3):195-200. doi: 10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.195. Epub 2015 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 26417479]

Piagkou M, Anagnostopoulou S, Kouladouros K, Piagkos G. Eagle's syndrome: a review of the literature. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2009 Jul:22(5):545-58. doi: 10.1002/ca.20804. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19418452]

Lavine MH, Stoopack JC, Jerrold TL. Calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1968 Jan:25(1):55-8 [PubMed PMID: 5235657]

Patil S, Ghosh S, Vasudeva N. Morphometric study of the styloid process of temporal bone. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2014 Sep:8(9):AC04-6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9419.4867. Epub 2014 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 25386413]

Dotiwala AK, Samra NS. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Tongue. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939559]

Laccourreye O, Orosco RK, Rubin F, Holsinger FC. Styloglossus muscle: a critical landmark in head and neck oncology. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Dec:135(6):421-425. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2017.11.012. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30341015]

Prades JM, Gavid M, Asanau A, Timoshenko AP, Richard C, Martin CH. Surgical anatomy of the styloid muscles and the extracranial glossopharyngeal nerve. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2014 Mar:36(2):141-6. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1162-9. Epub 2013 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 23835628]

Gözil R, Yener N, Calgüner E, Araç M, Tunç E, Bahcelioğlu M. Morphological characteristics of styloid process evaluated by computerized axial tomography. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2001 Nov:183(6):527-35 [PubMed PMID: 11766524]

Yavuz H, Caylakli F, Yildirim T, Ozluoglu LN. Angulation of the styloid process in Eagle's syndrome. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2008 Nov:265(11):1393-6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0686-9. Epub 2008 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 18427825]

Custodio AL, Silva MR, Abreu MH, Araújo LR, de Oliveira LJ. Styloid Process of the Temporal Bone: Morphometric Analysis and Clinical Implications. BioMed research international. 2016:2016():8792725 [PubMed PMID: 27703982]

Badhey A, Jategaonkar A, Anglin Kovacs AJ, Kadakia S, De Deyn PP, Ducic Y, Schantz S, Shin E. Eagle syndrome: A comprehensive review. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2017 Aug:159():34-38. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.04.021. Epub 2017 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 28527976]

Steinmann EP. Styloid syndrome in absence of an elongated process. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1968 Oct:66(4):347-56 [PubMed PMID: 5734501]

Steinmann EP. A new light on the pathogenesis of the styloid syndrome. Archives of otolaryngology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1970 Feb:91(2):171-4 [PubMed PMID: 4983008]

López F, Suárez C, Vander Poorten V, Mäkitie A, Nixon IJ, Strojan P, Hanna EY, Rodrigo JP, de Bree R, Quer M, Takes RP, Bradford CR, Shaha AR, Sanabria A, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Contemporary management of primary parapharyngeal space tumors. Head & neck. 2019 Feb:41(2):522-535. doi: 10.1002/hed.25439. Epub 2018 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 30549361]

Prasad SC, Piccirillo E, Chovanec M, La Melia C, De Donato G, Sanna M. Lateral skull base approaches in the management of benign parapharyngeal space tumors. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2015 Jun:42(3):189-98. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2014.09.002. Epub 2014 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 25270862]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoon CS, Lee BS, Kwon YD, Choi BJ, Lee JW, Lee HW, Yun SU, Ohe JY. Eagle's syndrome: a case report. Journal of the Korean Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2014 Feb:40(1):43-7. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2014.40.1.43. Epub 2014 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 24627843]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKamal A, Nazir R, Usman M, Salam BU, Sana F. Eagle syndrome; radiological evaluation and management. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2014 Nov:64(11):1315-7 [PubMed PMID: 25831655]

AlJulaih GH, Menezes RG. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Hyoid Bone. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969548]

Chuang WC, Short JH, McKinney AM, Anker L, Knoll B, McKinney ZJ. Reversible left hemispheric ischemia secondary to carotid compression in Eagle syndrome: surgical and CT angiographic correlation. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2007 Jan:28(1):143-5 [PubMed PMID: 17213444]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIlgüy M, Ilgüy D, Güler N, Bayirli G. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. The Journal of international medical research. 2005 Jan-Feb:33(1):96-102 [PubMed PMID: 15651721]

Ghosh LM, Dubey SP. The syndrome of elongated styloid process. Auris, nasus, larynx. 1999 Apr:26(2):169-75 [PubMed PMID: 10214896]

Casale M, Rinaldi V, Quattrocchi C, Bressi F, Vincenzi B, Santini D, Tonini G, Salvinelli F. Atypical chronic head and neck pain: don't forget Eagle's syndrome. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2008 Mar-Apr:12(2):131-3 [PubMed PMID: 18575165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNayak DR, Pujary K, Aggarwal M, Punnoose SE, Chaly VA. Role of three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction in the management of elongated styloid process: a preliminary study. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2007 Apr:121(4):349-53 [PubMed PMID: 17201986]

Petrović B, Radak D, Kostić V, Covicković-Sternić N. [Styloid syndrome: a review of literature]. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo. 2008 Nov-Dec:136(11-12):667-74 [PubMed PMID: 19177834]

Prasad KC, Kamath MP, Reddy KJ, Raju K, Agarwal S. Elongated styloid process (Eagle's syndrome): a clinical study. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2002 Feb:60(2):171-5 [PubMed PMID: 11815916]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEttinger RL, Hanson JG. The styloid or "Eagle" syndrome: an unexpected consequence. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1975 Sep:40(3):336-40 [PubMed PMID: 1058420]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJalisi S, Jamal BT, Grillone GA. Surgical Management of Long-standing Eagle's Syndrome. Annals of maxillofacial surgery. 2017 Jul-Dec:7(2):232-236. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_53_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29264291]

Bokhari MR, Graham C, Mohseni M. Eagle Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613540]

Murthy PS, Hazarika P, Mathai M, Kumar A, Kamath MP. Elongated styloid process: an overview. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 1990 Aug:19(4):230-1 [PubMed PMID: 2120364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence