Introduction

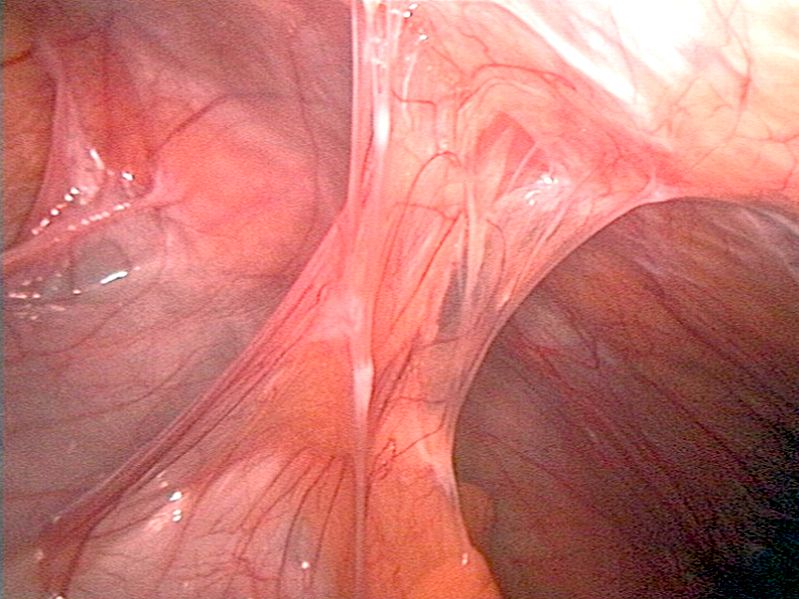

Bowel adhesions are irregular bands of scar tissue that form between 2 structures that are normally not bound together. The bands of tissue can develop when the body is healing from any disturbance of the tissue that occurs secondary to surgery, infection, trauma, or radiation. While the abdominal adhesions that form can be a normal response to the injury of the peritoneal surface, they can be the cause of significant morbidity, including adhesive small bowel obstruction, infertility in females, and chronic abdominal pain, and they can create a difficult environment for future surgeries [1]. See Image. Adhesions to the Abdominal Wall. Complications of subsequent surgery when adhesions are present may include difficult abdominal access and distorted anatomy, inability to perform laparoscopic surgery safely, inadvertent injury to other organs, increased duration of surgery, and increased blood loss.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Prior abdominal surgery is the most likely source of abdominal adhesions in the Western world. The surgeries most likely associated with adhesive small bowel obstruction are open gynecologic procedures, the formation of the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, and, lastly, open colectomy.[2] Other causes of adhesions include (but are not limited to) trauma, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, peritonitis (eg, tuberculous peritonitis), pelvic inflammatory disease, and abdominal or pelvic radiation. Congenital conditions such as malrotation may also be associated with adhesions known as Ladd's bands.[3][4]

Epidemiology

Adhesions account for approximately 1% of all general surgical admissions and 3% of all laparotomies. The United States is estimated to spend over $2 billion annually on managing adhesion-related complications.[5] Medical malpractice claims from cases involving adhesions most likely arise due to failure to warn patients during the consenting process of possible visceral injuries, failure to use specific preventative measures, and failure to diagnose or delayed diagnosis of complications.

Pathophysiology

A repair response is initiated when the peritoneal surface is injured during surgery or a traumatic event. The formation of adhesions involves a complex interaction of cytokines and growth factors secreted by cells near the area of injury. The response to injury begins immediately with hemostasis and coagulation, which release several chemical messengers. The most abundant messenger cells are the leukocytes, specifically the macrophage and mesothelial cells.[6][7] Macrophages send a signal that attracts new mesothelial cells that re-epithelialize the entire injured peritoneal surface (as opposed to traditional wound healing that heals from edge to edge). This response goes through an immediate inflammatory phase, peaking on days 4 to 5. The presence of adhesions depends mainly on the balance of fibrin deposition to degradation (fibrinolysis).[8]

A fibrin gel matrix is necessary for the formation of adhesions. Several enzyme systems work to break apart fibrin in the peritoneum that is protective against adhesions, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which can remove the fibrin gel matrix and reduce the incidence of adhesions. The extent of fibrinolysis and contact with damaged surfaces are key factors in determining adhesion formation. Incomplete fibrinolysis and poor resorption of degradation products allow connective tissue scarring and adhesions to develop, ultimately allowing the ingrowth of fibroblasts, capillaries, and nerves.[9]

History and Physical

The majority of patients who have bowel adhesions are asymptomatic. Approximately 75% of all patients presenting with symptoms related to adhesive disease have a history of prior abdominal surgery. The remaining 25% have a history of intra-abdominal or pelvic inflammatory processes, which can include malignancies.[3] Symptomatic patients typically manifest as intestinal obstruction (complete or partial)[10], chronic pain, and infertility in females.

- Adhesions are responsible for most cases of intestinal obstruction in Western countries. Any patient with prior abdominal or pelvic surgery presenting with obstruction should be suspected of having bowel adhesions. Most commonly, these patients describe nausea, vomiting, cramping, and obstipation. Periumbilical pain with cramping is typical. More focal pain may indicate peritoneal irritation. The sudden onset of severe pain may suggest acute intestinal ischemia and possible perforation. The physical exam may demonstrate a dehydrated patient with a distended abdomen and variations in bowel sounds on auscultation. These can be high-pitched tinkling or absent sounds depending on whether or not the bowel is distended with air or fluid.[10]

- Chronic abdominal pain or pelvic pain can be attributed to adhesions. While this relationship is poorly understood, there is evidence that extensive adhesions may limit the natural mobility of organs, resulting in visceral pain.

- Adhesions can be a source of infertility in females. Interference with ovum capture and transport or from tubal or intrauterine adhesions can hinder sperm transport and embryo implantation.[11]

A complete physical evaluation of the abdomen should be performed for any patient with suspicion of symptoms related to adhesions. Symptoms of obstruction and certainly of peritonitis should prompt surgical consultation.

Evaluation

An adhesion diagnosis is typically made when clinical suspicion and a detailed history indicate prior risk factors. Intra-abdominal examination in the form of laparoscopy or laparotomy is the only direct way to confirm the diagnosis of adhesions. Imaging such as plain films, ultrasound, magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and small bowel contrast study can be used; however, these are less reliable than direct visualization for identifying bowel adhesions causing obstruction but can be valuable in diagnosing obstruction.[12][13] Signs such as the "fat-bridging sign": a cord-like formation that contains mesenteric fat that forms a connection across the peritoneum; twisting or whirling of the mesentery (whirl sign); and anchoring of the omentum are specific signs of obstruction that can be seen in patients presenting with obstruction from adhesions.

The typical laboratory evaluation includes a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and lactic acid. Although these are non-specific, they may help indicate the severity of obstruction and the potential of small bowel ischemia. Arterial blood gas and blood cultures should be considered in those with systemic signs: fever, tachycardia, hypotension, and altered mental status. Metabolic alkalosis is often seen secondary to vomiting, but metabolic acidosis may also be secondary to bowel ischemia. Other laboratory studies, such as procalcitonin, can also be utilized to evaluate the level of inflammation.[14]

Treatment / Management

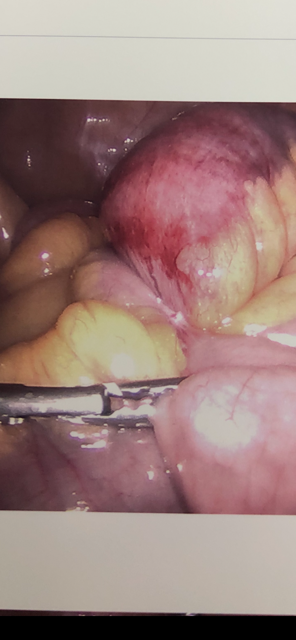

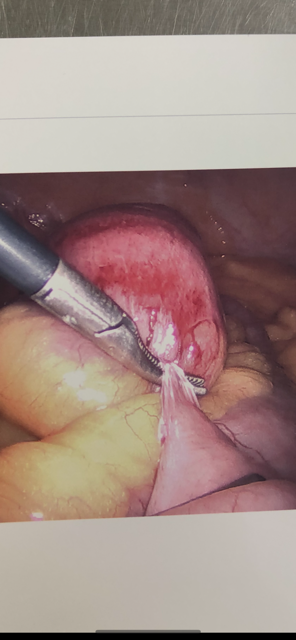

Most of the treatment of adhesive disease is centered around the manifestations of symptoms, such as bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions. The initial treatment of these patients includes intravenous fluid resuscitation and electrolyte replacement. If necessary, a surgical consult should also be obtained for possible surgery (adhesiolysis). Oral intake should be minimized in outpatient situations, and those requiring hospitalization should have nothing by mouth. Generally, imaging in plain film and/or computed tomography scans is performed to evaluate the obstruction. Any evidence of complete bowel obstruction, closed-loop obstruction, ischemia, necrosis, or perforation on imaging is an indication for immediate surgery. See Images. Closed-Loop Bowel Obstruction due to Adhesion, Closed-Loop Bowel Obstruction.

Often, nasogastric tube placement is necessary for bowel decompression and the management of nausea and vomiting.[15][16] Pain control is done with intravenous pain medications. However, unrelenting pain is often an indication to proceed with operative exploration. In addition, opiates decrease bowel function and should be used sparingly. Nonoperative management of bowel obstruction can often be successful.[17][18] Bowel rest with nasogastric tube placement for decompression can result in the resolution of obstruction. Studies have shown that administering a water-soluble contract via nasogastric tube or orally can also improve the success of nonoperative management of bowel obstructions. There are differing methods for administering contrast, but repeated plain films are generally performed in succession to ensure contrast passage into the colon. This can indicate that the obstructive process is resolving. Extensive exploration is considered if contrast does not readily pass into the colon (usually within 24 hours). (B2)

Other indications for surgical intervention include increasing abdominal pain, ongoing high output from the nasogastric tube, new instability of vital signs, or increased inflammatory markers such as lactic acid or white blood cell count. Diagnosis of these obstruction complications is based on clinical and radiological examination. If suspected, the patient should promptly be taken to the operating room for abdominal exploration.[19][20][21] Patients with peritonitis should have a prompt surgical consultation. Definitive management for bowel adhesions causing symptoms is laparoscopy or laparotomy with adhesiolysis. As mentioned, these procedures are not without risks, and full disclosure of risks vs. benefits should be undertaken with the patient/family when feasible. There is strong evidence that minimally invasive surgery with laparoscopy/robotic surgery can prevent the formation of adhesions compared to open (laparotomy) and should be attempted if possible.[22] Patients with a chronic disease process such as those with infertility suspected to be due to adhesions or inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn or ulcerative colitis) may be observed and at times, followed as an outpatient.[23](A1)

Operative Care

- Gentle tissue handling: meticulous hemostasis and gentle, minimal tissue handling are paramount. Preventing serosal injury by minimizing trauma, excess bleeding, and ischemia and keeping the surgical field moist is recommended.

- Laparotomy sponges are abrasive and should be avoided. When abdominal or pelvic packing is required, place laparotomy sponges in sterile plastic bags or drapes to minimize tissue injury and adhesion formation.

- Preventing foreign body reaction to excess suture, lint, or talc minimizes fibrin deposition. Silk sutures should be avoided as they are fibrogenic.

- Adhesion occurrence is similar regardless of the closure of the peritoneum after laparotomy.

- Minimally invasive surgery techniques minimize tissue handling and create smaller abdominal incisions, both minimizing bowel adhesions. However, this does not guarantee the prevention of adhesions; longer surgery time and higher insufflation pressure can increase the risk of adhesions.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for bowel adhesions includes:

- Acute cholangitis

- Cholecystitis and biliary colic

- Alcoholic ketoacidosis

- Constipation

- Diverticulitis

- Dysmenorrhea

- Early pregnancy loss

- Endometriosis

- Appendicitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

Prognosis

There is no known reliable method to resolve bowel adhesions without surgery. Patients who present with symptoms due to adhesions are at high risk of recurrent symptoms. The risk of recurrence of bowel obstruction increases with increasing episodes of obstruction. Most occur within 5 years of the previous episode, but a considerable risk remains 10 to 20 years later. Surgical treatment can decrease the risk of recurrent admissions due to bowel obstruction; however, the risk of new surgically treated episodes of obstruction is unchanged. Patients who have been treated for symptomatic adhesions experience more abdominal pain than the general population.[24][25]

Complications

Complications of surgery performed for intra-abdominal adhesions are similar to complications from any intra-abdominal surgery. These can include bleeding, infection, damage to surrounding structures, including enterotomies, and increased risk for the formation of adhesions in the future. Patients who undergo surgery for adhesions are also at risk for cardiopulmonary complications related to anesthesia as well as thromboembolic events.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative care for patients who have undergone surgery for bowel obstruction is focused on ensuring the resolution of obstructive symptoms and the ability of the patient to tolerate oral intake. Generally, patients are started on a clear liquid diet and advance as tolerated. The resumption of bowel function can be confirmed clinically (if the patient is passing flatus/stool) and radiographically.

Consultations

A general surgeon should evaluate patients with symptoms suspicious of complications of intra-abdominal adhesions. If there is infertility, an obstetrician should be consulted. A colorectal surgeon can also be consulted, particularly in cases related to inflammatory bowel disease.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery should be informed that adhesions are a possible consequence and can be associated with long-term complications. Patients should be educated on the signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction and told to present for evaluation if any of these are present - particularly obstipation, nausea/vomiting, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain.

Pearls and Other Issues

An area of research and a vast field for improvement includes the prevention of peritoneal adhesions. While pharmacologic methods have not been approved, the focus has been placed on barrier agents to prevent adhesions and surgical techniques. The fundamentals behind prevention include minimizing injury, creating a barrier between injured surfaces, preventing excessive coagulation of the serous exudate, removing or dissolving deposited fibrin, minimizing fibroblastic response to tissue injury, enhancing recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and novel fibrinolytic.[26]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The prevention of adhesions includes the coordination of care by the interprofessional team that includes nurses, a general surgeon, and an anesthesiologist. Prompt recognition of bowel adhesions by emergency department staff, primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and surgeons can mitigate complications. One of the causes of bowel obstruction is adhesions. While, in some cases, the bowel obstruction caused by adhesions may spontaneously resolve, some patients may require surgery to lyse the adhesions. Operating room nurses should assist surgeons using the measures described above. Emergency and anesthesia nurses provide initial and postoperative care, reporting changes in condition to the surgeon. They also assist with patient and family education. Pharmacists review medications prescribed and assess for drug-drug interactions. Unfortunately, recurrences are common, and some patients may require repeat adhesiolysis.[13]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brüggmann D, Tchartchian G, Wallwiener M, Münstedt K, Tinneberg HR, Hackethal A. Intra-abdominal adhesions: definition, origin, significance in surgical practice, and treatment options. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2010 Nov:107(44):769-75. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0769. Epub 2010 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 21116396]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKrielen P, Ten Broek RPG, van Dongen KW, Parker MC, Griffiths EA, van Goor H, Stommel MWJ. Adhesion-related readmissions after open and laparoscopic colorectal surgery in 16 524 patients. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2022 Apr:24(4):520-529. doi: 10.1111/codi.16024. Epub 2022 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 34919765]

Jang Y, Jung SM, Heo TG, Choi PW, Kim JI, Jung SW, Jun H, Shin YC, Um E. Determining the etiology of small bowel obstruction in patients without intraabdominal operative history: a retrospective study. Annals of coloproctology. 2022 Dec:38(6):423-431. doi: 10.3393/ac.2021.00710.0101. Epub 2021 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 34875819]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJena SS, Obili RCR, Das SAP, Ray S, Yadav A, Mehta NN, Nundy S. Intestinal obstruction in a tertiary care centre in India: Are the differences with the western experience becoming less? Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2021 Dec:72():103125. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.103125. Epub 2021 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 34925821]

Wilson MS. Practicalities and costs of adhesions. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2007 Oct:9 Suppl 2():60-5 [PubMed PMID: 17824972]

Junga A, Pilmane M, Ābola Z, Volrāts O. The Distribution of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Human Beta-Defensin-2 (HBD-2), and Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) in Intra-Abdominal Adhesions in Children under One Year of Age. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2018:2018():5953095. doi: 10.1155/2018/5953095. Epub 2018 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 30692872]

Giusto G, Iussich S, Tursi M, Perona G, Gandini M. Comparison of two different barbed suture materials for end-to-end jejuno-jejunal anastomosis in pigs. Acta veterinaria Scandinavica. 2019 Jan 5:61(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13028-018-0437-x. Epub 2019 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 30611301]

Hu Q, Xia X, Kang X, Song P, Liu Z, Wang M, Lu X, Guan W, Liu S. A review of physiological and cellular mechanisms underlying fibrotic postoperative adhesion. International journal of biological sciences. 2021:17(1):298-306. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.54403. Epub 2021 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 33390851]

Herrick SE, Wilm B. Post-Surgical Peritoneal Scarring and Key Molecular Mechanisms. Biomolecules. 2021 May 5:11(5):. doi: 10.3390/biom11050692. Epub 2021 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 34063089]

Aka AA, Wright JP, DeBeche-Adams T. Small Bowel Obstruction. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2021 Jul:34(4):219-226. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1725204. Epub 2021 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 34305470]

Arab W. Diagnostic laparoscopy for unexplained subfertility: a comprehensive review. JBRA assisted reproduction. 2022 Jan 17:26(1):145-152. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20210084. Epub 2022 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 34751015]

Pirotte B, Inaba K, Schellenberg M, Recinos G, Lam L, Benjamin E, Matsushima K, Demetriades D. Intraoperative Consultations to Acute Care Surgery at a Level I Trauma Center. The American surgeon. 2019 Jan 1:85(1):82-85 [PubMed PMID: 30760350]

Behman R, Nathens AB, Mason S, Byrne JP, Hong NL, Pechlivanoglou P, Karanicolas P. Association of Surgical Intervention for Adhesive Small-Bowel Obstruction With the Risk of Recurrence. JAMA surgery. 2019 May 1:154(5):413-420. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5248. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30698610]

Sahin GK, Gulen M, Acehan S, Firat BT, Isikber C, Kaya A, Segmen MS, Simsek Y, Sozutek A, Satar S. Do biomarkers have predictive value in the treatment modality of the patients diagnosed with bowel obstruction? Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992). 2022 Jan:68(1):67-72. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.20210771. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34909965]

Toto-Morales JG, Martínez-Munive Á, Quijano-Orvañanos F. Clinical and tomographic features associated with surgical management in adhesive small bowel obstruction patients. Cirugia y cirujanos. 2021:89(5):588-594. doi: 10.24875/CIRU.20000716. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34665166]

Shinohara K, Asaba Y, Ishida T, Maeta T, Suzuki M, Mizukami Y. Nonoperative management without nasogastric tube decompression for adhesive small bowel obstruction. American journal of surgery. 2022 Jun:223(6):1179-1182. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.11.029. Epub 2021 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 34872712]

Lawrence EM, Pickhardt PJ. Water-Soluble Contrast Challenge for Suspected Small-Bowel Obstruction: Technical Success Rate, Accuracy, and Clinical Outcomes. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2021 Dec:217(6):1365-1366. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.26132. Epub 2021 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 34161132]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNishie H, Shimura T, Katano T, Iwai T, Itoh K, Ebi M, Mizuno Y, Togawa S, Shibata S, Yamada T, Mizushima T, Inagaki Y, Kitagawa M, Nojiri Y, Tanaka Y, Okamoto Y, Matoya S, Nagura Y, Inagaki Y, Koguchi H, Ono S, Ozeki K, Hayashi N, Takiguchi S, Kataoka H. Long-term outcomes of nasogastric tube with Gastrografin for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2022 Jan:37(1):111-116. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15681. Epub 2021 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 34478173]

Long B, Robertson J, Koyfman A. Emergency Medicine Evaluation and Management of Small Bowel Obstruction: Evidence-Based Recommendations. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Feb:56(2):166-176. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.10.024. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30527563]

Quah GS, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for adhesional small bowel obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Surgical endoscopy. 2019 Oct:33(10):3209-3217. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6604-3. Epub 2018 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 30460502]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOzturk E, van Iersel M, Stommel MM, Schoon Y, Ten Broek RR, van Goor H. Small bowel obstruction in the elderly: a plea for comprehensive acute geriatric care. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2018:13():48. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0208-z. Epub 2018 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 30377439]

Gómez D, Cabrera LF, Pedraza M, Mendoza A, Pulido J, Villarreal R, Urrutia A, Sanchez-Ussa S, Saverio SD. Minimal invasive surgery for multiple adhesive small bowel obstruction: Results of a comparative multicenter study. Cirugia y cirujanos. 2021:89(6):710-717. doi: 10.24875/CIRU.20000895. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34851576]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSinopoulou V, Gordon M, Dovey TM, Akobeng AK. Interventions for the management of abdominal pain in ulcerative colitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021 Jul 22:7(7):CD013589. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013589.pub2. Epub 2021 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 34291816]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePodda M, Khan M, Di Saverio S. Adhesive Small Bowel Obstruction and the six w's: Who, How, Why, When, What, and Where to diagnose and operate? Scandinavian journal of surgery : SJS : official organ for the Finnish Surgical Society and the Scandinavian Surgical Society. 2021 Jun:110(2):159-169. doi: 10.1177/1457496920982763. Epub 2021 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 33511902]

Fevang BT, Fevang J, Lie SA, Søreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Long-term prognosis after operation for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Annals of surgery. 2004 Aug:240(2):193-201 [PubMed PMID: 15273540]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNakashima M, Takeuchi M, Kawakami K. Effectiveness of barrier agents for preventing postoperative bowel obstruction after laparoscopic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Surgery today. 2021 Aug:51(8):1335-1342. doi: 10.1007/s00595-021-02258-w. Epub 2021 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 33646411]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence