Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common and treatable disease characterized by progressive airflow limitation and tissue destruction. It is associated with structural lung changes due to chronic inflammation from prolonged exposure to noxious particles or gases most commonly cigarette smoke. Chronic inflammation causes airway narrowing and decreased lung recoil. The disease often presents with symptoms of cough, dyspnea, and sputum production. Symptoms can range from being asymptomatic to respiratory failure. [1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

COPD is caused by prolonged exposure to harmful particles or gases. Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of COPD worldwide. Other causes may include second-hand smoke, environmental and occupational exposures, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). [1]

Epidemiology

COPD is primarily present in smokers and those greater than age 40. Prevalence increases with age and it is currently the third most common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2015, the prevalence of COPD was 174 million and there were approximately 3.2 million deaths due to COPD worldwide. However, the prevalence is likely to be underestimated due to the underdiagnosis of COPD. [1][2]

Pathophysiology

COPD is an inflammatory condition involving the airways, lung parenchyma, and pulmonary vasculature. The process is thought to involve oxidative stress and protease-antiprotease imbalances. Emphysema describes one of the structural changes seen in COPD where there is destruction of the alveolar air sacs (gas-exchanging surfaces of the lungs) leading to obstructive physiology. In emphysema, an irritant (e.g., smoking) causes an inflammatory response. Neutrophils and macrophages are recruited and release multiple inflammatory mediators. Oxidants and excess proteases leading to the destruction of the air sacs. The protease-mediated destruction of elastin leads to a loss of elastic recoil and results in airway collapse during exhalation. [1][3]

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a rare cause of emphysema which involves a lack of antiproteases and the imbalance leaves the lung parenchyma at risk for protease-mediated damage. AATD is caused by misfolding of the mutated protein which can accumulate in the liver. AATD should be suspected in COPD patients who present with liver damage. As opposed to smoking-related emphysema, AATD primarily involves the lower lobes. [1]

The inflammatory response and obstruction of the airways cause a decrease in the forced expiratory volume (FEV1) and tissue destruction leads to airflow limitation and impaired gas exchange. Hyperinflation of the lungs is often seen on imaging studies and occurs due to air trapping from airway collapse during exhalation. The inability to fully exhale also causes elevations in carbon dioxide (CO2) levels. As the disease progresses, impairment of gas exchange is often seen. The reduction in ventilation or increase in physiologic dead space leads to CO2 retention. Pulmonary hypertension may occur due to diffuse vasoconstriction from hypoxemia. [1][3]

Acute exacerbations of COPD are common and usually occur due to a trigger (e.g., bacterial or viral pneumonia, environmental irritants). There is an increase in inflammation and air trapping often requiring corticosteroid and bronchodilator treatment. [1][4]

History and Physical

COPD will typically present in adulthood and often during the winter months. Patients usually present with complaints of chronic and progressive dyspnea, cough, and sputum production. Patients may also have wheezing and chest tightness. While a smoking history is present in most cases, there are many without such history. They should be questioned on exposure to second-hand smoke, occupational and environmental exposures, and family history. Those with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD should be asked about previous exacerbations, nighttime awakenings, inhaler usage, and the impact of the disease on activity level. Patients should be questioned on their past medical history for other diseases such as asthma, allergies, and childhood respiratory infections. Those with liver disease, basilar emphysema, and a family history of emphysema should raise suspicion for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Acute exacerbations of COPD usually present with increased dyspnea, productive cough, and wheezing.

Patients with COPD may have multiple physical findings as follows:

General [1]

- Significant respiratory distress in acute exacerbations

- Muscle wasting

Lungs [5]

- Accessory respiratory muscle use

- Prolonged expiration

- Wheezing

- Pursed-lip breathing

Chest [5]

- Increased anterior-posterior chest wall diameter (barrel chest)

Skin [6]

- Central cyanosis when arterial oxygenation is low

Extremities [1]

- Digital clubbing

- Lower extremity edema in right heart failure

Evaluation

COPD is often evaluated in patients with relevant symptoms and risk factors. The diagnosis is confirmed by spirometry. Other tests may include a 6-minute walk test, laboratory testing, and radiographic imaging. [1]

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is essential in the diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of COPD. Spirometry is performed before and after administering an inhaled bronchodilator. Inhaled bronchodilators may be a short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA), short-acting anticholinergic, or a combination of both. A ratio of the forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) less than 0.7 confirms the diagnosis of COPD. Patients with a significantly reduced FEV1 and signs of dyspnea should be evaluated for oxygenation with pulse oximetry or arterial blood gas analysis. [7][8]

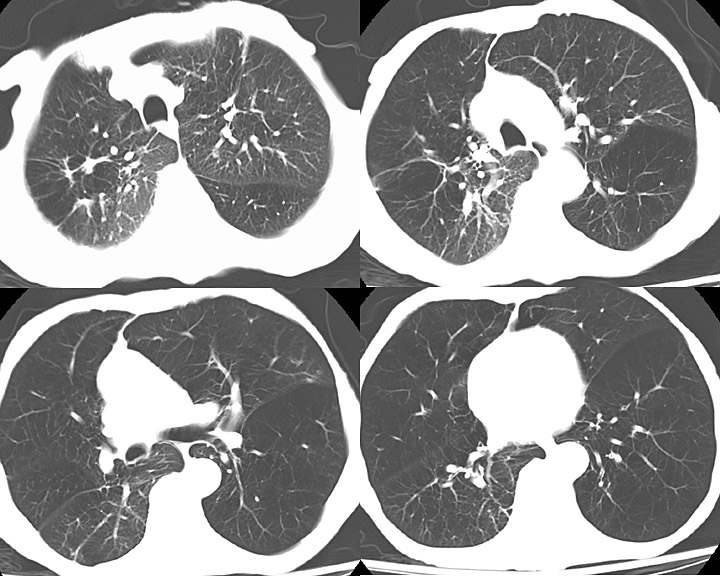

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) is a program initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The program is recognized worldwide for providing updated and detailed reports on the recommendations for the diagnosis and management of COPD. The GOLD recommendations are often used to assess disease severity and choice of therapy. [1]

The 2019 GOLD report outlines a simplified method of evaluating and choosing the initial treatment for patients with COPD. The refined ABCD assessment tool guides healthcare providers to determine the severity of disease and the GOLD group classification. Once the diagnosis of COPD is confirmed by spirometry (FEV1/FVC <0.7), the FEV1 is used to determine the severity (GOLD classification 1-4). The GOLD group (A-D) is then determined by the severity of symptoms and the history of exacerbations. The assessment of COPD is summarized in Figure 1. [1]

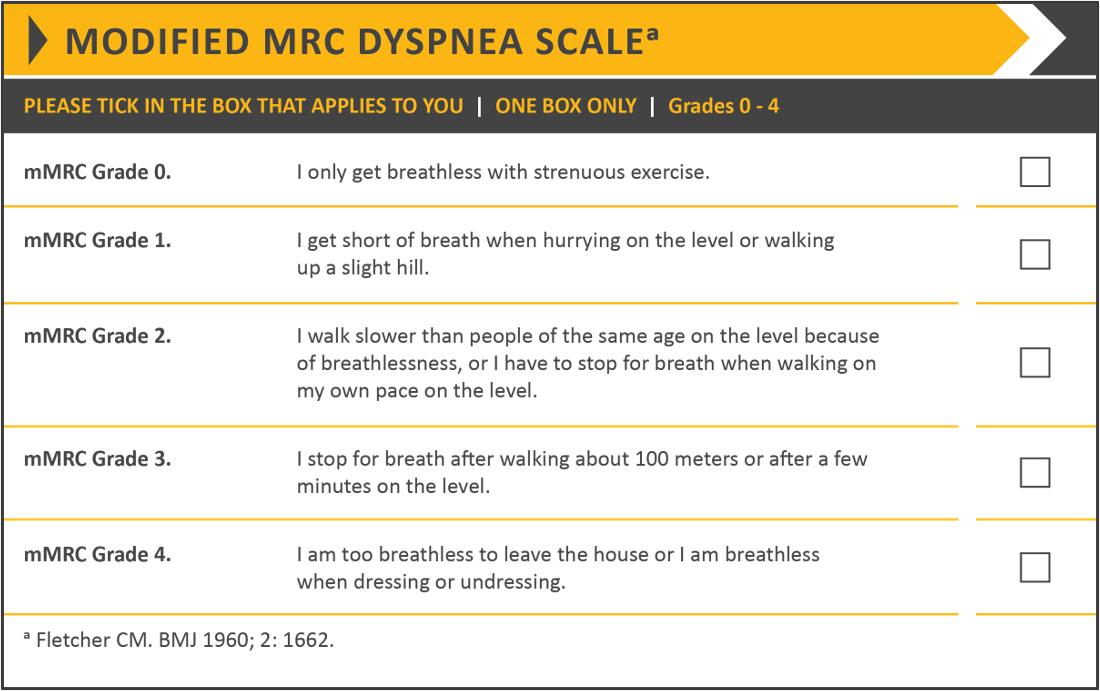

Symptom severity is evaluated using the modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire (Table 1) and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) (Table 2). The mMRC questionnaire assesses the degree of breathlessness on a scale of 0-4 with 4 being the most severe. The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) provides a score on eight functional parameters to measure the impact of the disease on a patient’s daily life. [1][9]

A 6-minute walk test is commonly performed to assess the submaximal functional capacity of a patient. This test is performed indoors on a flat and straight surface. The length of the hallway is usually 100 feet and the test measures the distance the patient walks over a period of 6 minutes. [10]

Laboratory testing often requires a complete blood count to assess for infection, anemia, and polycythemia. Alpha-1 antitrypsin levels should be checked for other causes of COPD.

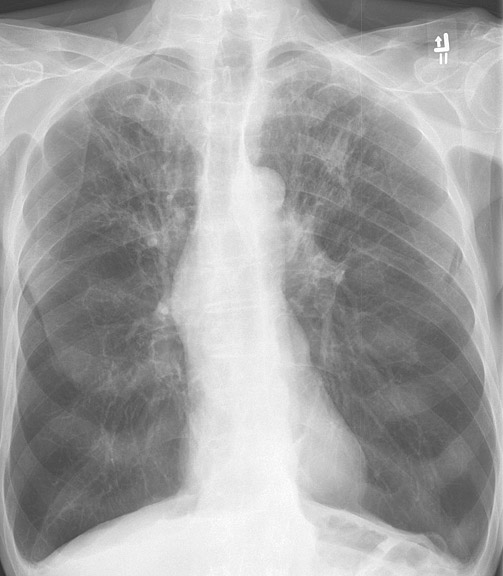

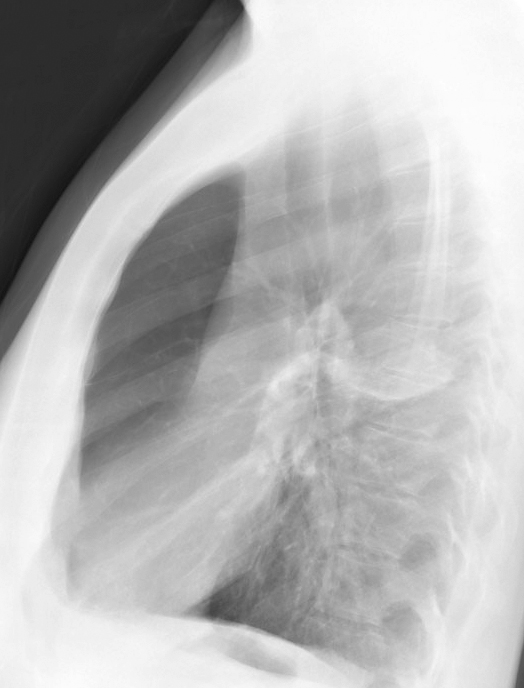

Radiographic imaging includes a chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT). Chest x-rays may show hyperinflation, flattening of the diaphragm, and increased anterior-posterior diameter. In cases of chronic bronchitis, bronchial wall thickening may be present. CT imaging may be useful in patients with bronchiectasis, malignancy, or if planning surgical procedures. CT of the chest in patients with COPD will be significant for centrilobular emphysema. Bullae may be present in the subpleural regions. [11]

A biopsy is not required for the diagnosis of COPD. Histopathologic findings include an increase in inflammatory cells, structural changes, and lymphoid follicles.

Acute exacerbation of COPD is an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms. Assessing severity is often based on the model developed by Anthonisen and colleagues which classifies severity by the presence of worsening dyspnea, sputum volume, and purulence. Mild exacerbations are defined by the presence of 1 of these symptoms in addition to one of the following: increased wheezing, increased cough, fever without another cause, upper respiratory infection within 5 days, or an increase in heart rate or respiratory rate from the patient's baseline. Moderate and severe exacerbations are defined by the presence of 2 or all 3 of the symptoms respectively. Patients may have acute respiratory failure and physical findings of hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Arterial blood gas analysis, chest imaging, and pulse oximetry are indicated. [1][8][12]

Treatment / Management

The primary goals of treatment are to control symptoms, improve the quality of life, and reduce exacerbations and mortality. The non-pharmacological approach includes smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation.

Annual influenza vaccination is recommended in all patients with COPD. Patients aged 65 and over should receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) at least one year apart. The PPSV23 is recommended for those aged 64 and younger with significant comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease). [1]

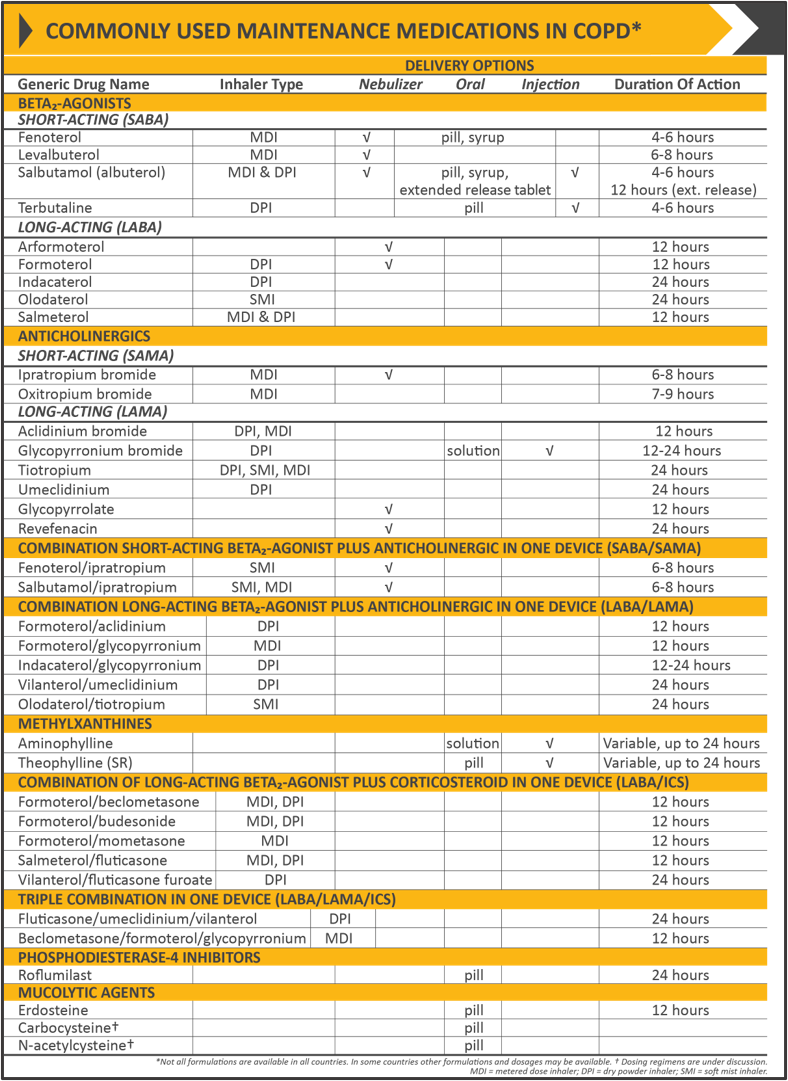

The classes of commonly used medications in COPD include bronchodilators (beta2-agonists, antimuscarinics, methylxanthines), inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), systemic glucocorticoids, phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors, and antibiotics.

Beta2-agonists work by relaxing the smooth muscle in the airways. SABAs and long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA) are commonly used in treatment. SABAs are used as needed to provide immediate relief. LABAs are typically used for maintenance therapy.

Antimuscarinics work by blocking the M3 muscarinic receptors in the smooth muscle and therefore preventing bronchoconstriction. Short-acting antimuscarinic agents (SAMA) like SABAs provide a rapid onset of action and are used on an as-needed basis. Long-acting antimuscarinic agents (LAMA), like LABAs, are used as maintenance therapy. [13]

Methylxanthines are also used in maintenance therapy, usually after LABA or LAMA treatment as additional relief. Methylxanthines work by relaxing the smooth muscle in the airways causing mild bronchodilation. The mechanism of action is unknown, however, it may be due to the inhibition of phosphodiesterase (PDE) III and IV. Theophylline is a commonly used methylxanthine and when used in combination with salmeterol has shown to provide significantly greater improvement in FEV1 compared to salmeterol alone. [14][15](A1)

Inhaled corticosteroids are often used in combination with LABAs and LAMAs to decrease inflammation. A combination of ICS and LABA has been shown to be more beneficial than either of the drugs when used alone. Physicians and patients should be aware of an increased risk of developing pneumonia when treated with an ICS. Oral glucocorticoids are not indicated for long-term use and can have multiple side effects. These should instead be reserved for the management of acute exacerbations. [16][17](A1)

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors work by inhibiting the breakdown of intracellular cyclic AMP and thus reduce inflammation. Roflumilast is a PDE4 inhibitor used for patients with severe disease and has been shown to decrease the number of exacerbations in this population. [18][19](A1)

Recent studies have shown that the use of azithromycin may reduce the number of exacerbations in patients with COPD. Azithromycin is typically prescribed as 250mg/day or 500mg three times weekly for one year. Physicians should use caution as this practice may promote bacterial resistance. Patients should also be monitored for QTc prolongation and impaired hearing. [20][21](A1)

Acute exacerbations of COPD can be managed in an outpatient or inpatient setting depending on the severity. The assessment of severity is discussed in the previous section. Mild cases can be treated in the outpatient setting with bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and antibiotics. For moderate and severe cases, inpatient management is indicated. Hospitalized patients often require oxygen and bronchodilator therapy in the form of a SABA with or without a SAMA. Long-acting bronchodilators are typically used when the patient becomes stable and ready for discharge. Oral corticosteroids may be used, however, intravenous corticosteroids have not shown to be more efficacious compared to oral and instead may cause increased side effects. Intravenous corticosteroids may be considered if patients have a contraindication to oral intake (e.g., aspiration risk or continuous BiPAP therapy). Antibiotics should be considered if there is suspicion for a bacterial infection. Oxygen therapy can range from a nasal cannula to mechanical ventilation depending on the severity of the exacerbation. [1][8][22](A1)

For long-term therapy, the choice of treatment varies and should be tailored to each patient. Management is largely based on the severity of the disease and symptoms as outlined by GOLD. See Figure 1 and Table 4 for initial and commonly used medications in the treatment of COPD. [1]

Severe cases may require surgical intervention including bullectomy, lung volume reduction surgery, or lung transplantation. Surgical intervention is indicated in severe conditions where symptoms are not controlled with medical therapy alone and may improve quality of life.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is indicated in all stages of COPD. It is a comprehensive plan that is tailored to patients and may involve therapies such as exercise training, education, and behavioral changes. Its purpose is to improve a patient's physical function and psychological condition. [23](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Asthma

- Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome

- Interstitial lung disease

- Bronchiolitis obliterans

- Diffuse panbronchiolitis

- Heart failure

- Thromboembolic disease

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Tuberculosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchiectasis

- Malignancy

Prognosis

The prognosis of COPD is variable based on adherence to treatment including smoking cessation and avoidance of other harmful gases. Patients with other comorbidities (e.g., pulmonary hypertension, cardiovascular disease, lung cancer) typically have a poorer prognosis. The airflow limitation and dyspnea are usually progressive.

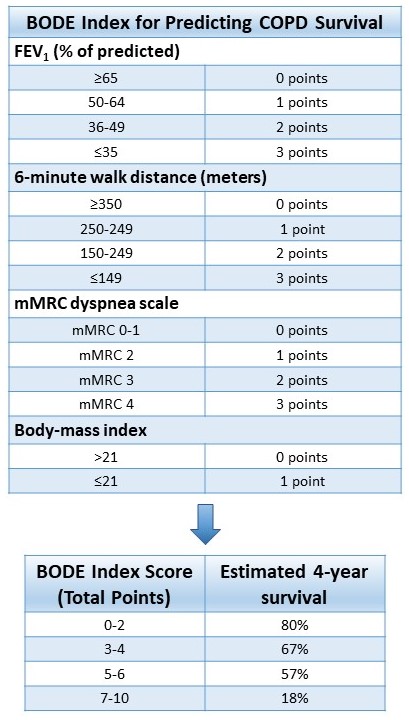

The BODE (Body-mass index (BMI), airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise capacity) index is a tool used to determine the risk of mortality in COPD. The BODE index is scored on a point scale of 1-10 based on the following criteria: FEV1 % of predicted, 6-minute walk distance, mMRC scale, and BMI. The cumulative score is then correlated with 4-year survival. The BODE index is illustrated in Table 4. [24]

Complications

- Acute exacerbation of COPD

- Acute and/or chronic respiratory failure

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Cor pulmonale

- Weight loss

- Bacterial infections

- Adverse reactions to glucocorticoids

Consultations

Management of patients with COPD requires a diverse team of health professionals that may include:

- Pulmonologist

- Thoracic surgeon if surgery is indicated

- Intensivist

- Respiratory therapist

- Palliative care

Deterrence and Patient Education

To prevent or to slow the progression of COPD, patients should be educated on the following [1]:

- Smoking cessation

- Avoid second-hand smoke exposure

- Reduce exposure to other harmful agents

- Common occupational/environmental exposures are listed below

- Inorganic substances - asbestos, beryllium, carbon dust, silica, chromium

- Organic substances - thermophilic fungi, avian droppings, bacterial species

- Unvented coal stoves

- Common occupational/environmental exposures are listed below

- Education on inhaler use technique

- Education and reinforcement on the importance of inhaler use

- Compliance with follow-up

- Adherence to the treatment plan

- Detection of worsening symptoms

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pearls and Other Issues

- COPD is a chronic inflammatory lung disease causing tissue destruction and irreversible airflow limitation

- Smoking is the most common risk factor worldwide

- Patients should be screened for AATD

- COPD most commonly affects adults >40 years old

- Diagnosis is made by spirometry with a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7

- Patients should avoid smoking and other harmful exposures

- Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all patients with COPD

- PCV13 and PPSV23 at least 1 year apart is recommended for patients aged 65 or greater

- PPSV23 is recommended in COPD patients under age 65 with significant comorbid conditions

- Pharmacologic treatment typically involves the use of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids

- Complications commonly include acute exacerbations, pulmonary hypertension, and bacterial pneumonia

- Patients with a smoking history who meet screening criteria should be monitored for lung cancer

- Criteria for lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography [25]

- Age 55-80

- 30+ pack-year smoking history

- Current smoker or quit within the past 15 years

- Criteria for lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography [25]

- Lung transplantation may improve functional capacity but not prolong survival

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimizing healthcare outcomes in patients with COPD involves collaboration between healthcare professionals and implementing comprehensive patient-tailored treatment plans. Healthcare professionals include primary care physicians, consultants, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and rehabilitation specialists. Patients should be educated regularly on smoking cessation and encouraged to adhere to treatment plans. Pulmonary rehabilitation plays a large role in improving outcomes. Rehabilitation has been shown to improve the quality of life, dyspnea, and exercise capacity in patients with COPD. [23] [Level 2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Frith P, Halpin DMG, Han M, López Varela MV, Martinez F, Montes de Oca M, Papi A, Pavord ID, Roche N, Sin DD, Stockley R, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Vogelmeier C. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. The European respiratory journal. 2019 May:53(5):. pii: 1900164. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00164-2019. Epub 2019 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 30846476]

GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2017 Sep:5(9):691-706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. Epub 2017 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 28822787]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStockley RA. Neutrophils and protease/antiprotease imbalance. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999 Nov:160(5 Pt 2):S49-52 [PubMed PMID: 10556170]

Parker CM, Voduc N, Aaron SD, Webb KA, O'Donnell DE. Physiological changes during symptom recovery from moderate exacerbations of COPD. The European respiratory journal. 2005 Sep:26(3):420-8 [PubMed PMID: 16135722]

Mattos WL, Signori LG, Borges FK, Bergamin JA, Machado V. Accuracy of clinical examination findings in the diagnosis of COPD. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia. 2009 May:35(5):404-8 [PubMed PMID: 19547847]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChangizi M, Rio K. Harnessing color vision for visual oximetry in central cyanosis. Medical hypotheses. 2010 Jan:74(1):87-91. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.045. Epub 2009 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 19699589]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, Hanania NA, Criner G, van der Molen T, Marciniuk DD, Denberg T, Schünemann H, Wedzicha W, MacDonald R, Shekelle P, American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Aug 2:155(3):179-91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21810710]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDecramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet (London, England). 2012 Apr 7:379(9823):1341-51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. Epub 2012 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 22314182]

FLETCHER CM, ELMES PC, FAIRBAIRN AS, WOOD CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. British medical journal. 1959 Aug 29:2(5147):257-66 [PubMed PMID: 13823475]

ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002 Jul 1:166(1):111-7 [PubMed PMID: 12091180]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShaker SB, Dirksen A, Bach KS, Mortensen J. Imaging in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2007 Jun:4(2):143-61 [PubMed PMID: 17530508]

Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GK, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of internal medicine. 1987 Feb:106(2):196-204 [PubMed PMID: 3492164]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMelani AS. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists. Expert review of clinical pharmacology. 2015:8(4):479-501. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1058154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26109098]

Ram FS, Jones PW, Castro AA, De Brito JA, Atallah AN, Lacasse Y, Mazzini R, Goldstein R, Cendon S. Oral theophylline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2002:2002(4):CD003902 [PubMed PMID: 12519617]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZuWallack RL, Mahler DA, Reilly D, Church N, Emmett A, Rickard K, Knobil K. Salmeterol plus theophylline combination therapy in the treatment of COPD. Chest. 2001 Jun:119(6):1661-70 [PubMed PMID: 11399688]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Sep 12:2012(9):CD006829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006829.pub2. Epub 2012 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 22972099]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNannini LJ, Poole P, Milan SJ, Kesterton A. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus inhaled corticosteroids alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Aug 30:2013(8):CD006826. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006826.pub2. Epub 2013 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 23990350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRabe KF. Update on roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. British journal of pharmacology. 2011 May:163(1):53-67. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01218.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21232047]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCalverley PM, Rabe KF, Goehring UM, Kristiansen S, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, M2-124 and M2-125 study groups. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. Lancet (London, England). 2009 Aug 29:374(9691):685-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61255-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19716960]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUzun S, Djamin RS, Kluytmans JA, Mulder PG, van't Veer NE, Ermens AA, Pelle AJ, Hoogsteden HC, Aerts JG, van der Eerden MM. Azithromycin maintenance treatment in patients with frequent exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COLUMBUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2014 May:2(5):361-8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70019-0. Epub 2014 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 24746000]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAlbert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, Casaburi R, Cooper JA Jr, Criner GJ, Curtis JL, Dransfield MT, Han MK, Lazarus SC, Make B, Marchetti N, Martinez FJ, Madinger NE, McEvoy C, Niewoehner DE, Porsasz J, Price CS, Reilly J, Scanlon PD, Sciurba FC, Scharf SM, Washko GR, Woodruff PG, Anthonisen NR, COPD Clinical Research Network. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Aug 25:365(8):689-98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104623. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21864166]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Jong YP, Uil SM, Grotjohan HP, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA, van den Berg JW. Oral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: a randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Chest. 2007 Dec:132(6):1741-7 [PubMed PMID: 17646228]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Feb 23:2015(2):CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. Epub 2015 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 25705944]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCelli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Mar 4:350(10):1005-12 [PubMed PMID: 14999112]

Tanoue LT, Tanner NT, Gould MK, Silvestri GA. Lung cancer screening. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015 Jan 1:191(1):19-33. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1777CI. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25369325]