Introduction

The esophagus, historically also spelled oesophagus, is a tubular, elongated organ of the digestive system which connects the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is the organ that food travels through to reach the stomach for further digestion. It follows a path that travels behind the trachea and heart, in front of the spinal column, and through the diaphragm before entering the stomach.[1][2]

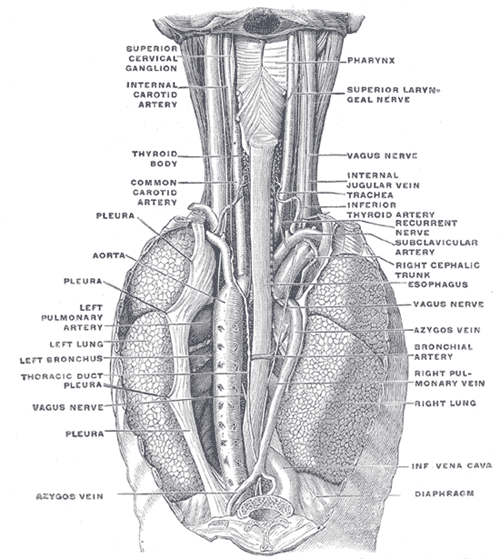

The esophagus is subdivided into three anatomical segments: cervical, thoracic, and abdominal. The cervical segment begins at the cricopharyngeus and terminates at the suprasternal notch. This segment lies just behind the trachea, to which it is joined via loose connective tissues. Posteriorly, prevertebral fascia connects the esophagus to the bodies of sixth through eighth cervical vertebra. The thoracic duct can be found on the left side of the sixth cervical vertebra. The carotid sheath and the lower poles of the lateral thyroid gland can be found lateral to the esophagus in the lower part of the neck. The thoracic segment lies between the vertebral column and the trachea in the superior mediastinum, extending from the suprasternal notch to the diaphragm. As the esophagus is followed distally, it passes behind the aortic arch at the level of the T4 through T5 intervertebral discs and enters the posterior mediastinum. The final segment, the abdominal segment, runs from the diaphragm to the fundus of the stomach. This segment descends and passes through the right crus of the diaphragm at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra and into the cardia of the stomach at the eleventh thoracic vertebra level.

The organ is typically about nine to ten inches (23 to 25 cm) long in fully grown adults, with sphincters located at each of its proximal and distal extremities, a mucosa-lined lumen and connective tissue, and smooth muscle outer composition. The sphincter located anteriorly, the upper esophageal sphincter, allows for the single direction passage of food into the esophagus, and anteriorly, the lower esophageal sphincter allows for the single direction passage of food into the stomach. [3][4][5]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The primary function of the esophagus is to transport food entering the mouth through the throat and into the stomach. This function begins at the very beginning of the esophagus, following some taste buds located on the organ, at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). The UES, also termed the pharyngoesophageal sphincter, is a circular bundle of muscle tissue which normally remains closed in a contracted position. During swallowing, the muscles relax temporarily and allow the passage of materials or bolus in the form of food, drink, mucus, and saliva into the esophagus. Next, the bolus travels into the esophageal body. Peristaltic movement propels the bolus down the esophagus via primary and secondary peristalsis. During the pharyngeal stage of swallowing, the muscular walls of the pharynx contract providing a strong initial peristaltic motion of the bolus and sending the bolus through the UES with kinetic energy. This peristaltic wave continues into the esophagus and constitutes the primary peristalsis. If the primary peristalsis is not sufficient to carry the bolus to the stomach, realized by the body as continued distention of the esophagus following primary peristalsis, secondary peristalsis initiates and continues until the bolus is successfully moved to the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), also termed the cardiac sphincter and cardioesophageal sphincter, is located slightly more than an inch (about 3 cm) proximally from where the esophagus meets the stomach. Similar to the UES, the LES is normally contracted and closed, primarily preventing stomach contents from entering the esophagus body. The LES is controlled involuntarily and is triggered to open during esophageal peristalsis, thereby allowing the propelled bolus to enter the stomach and completing the primary function of the esophagus. While the primary function of the esophagus is to allow for the passage of material from the mouth and throat to the stomach, it is also a means by which material may be expelled from the body from the stomach and out the mouth in cases of vomiting, eructation, and at times when the gag reflex is initiated. However, this function is typically not desirable as food being expelled via this route may result in malnutrition and possible damage to the esophagus from gastric acid.

Embryology

During the fourth week of human development, the embryo elongates and the yolk sac is divided into intra-embryonic and extraembryonic regions. The origin of the digestive tube occurs in the intra-embryonic region, with the regression and disappearance of the extraembryonic portion occurring around week 12, at which time the digestive system divides into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The continued development of the foregut gives rise to the esophagus.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The esophagus has a rich supply of arterial blood coupled with venous drainage, with these being segmental. The cervical esophagus and UES are supplied with blood via branches of the inferior thyroid artery. The thoracic esophagus is supplied by the aortic esophageal arteries which are at the terminal branches of the bronchial arteries. The abdominal segment and LES are supplied with blood via the left gastric artery and a left phrenic artery branch. These arteries flow into the submucosa of the esophagus as a dense network. Venous blood then flows into the superior vena cava from the aforementioned submucosal plexus. The azygos system provides drainage for the proximal and distal segments of the esophagus while the midsection of the esophagus receives drainage via auxiliaries of the left gastric vein which branches from the portal vein.[6]

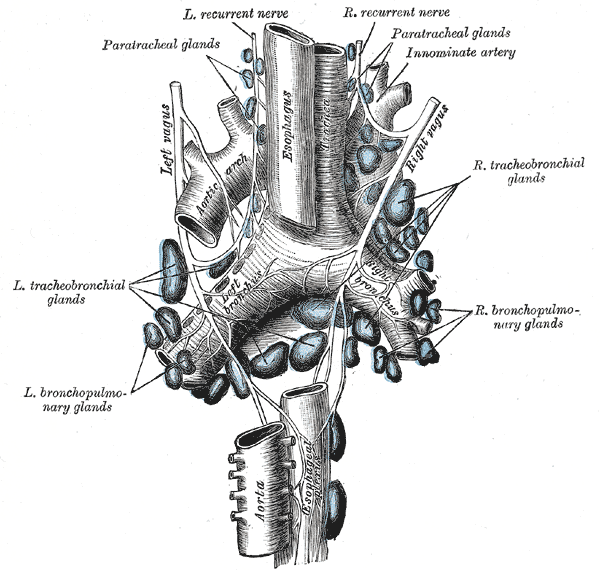

Lymph channels and lymph nodes together provide the esophagus with lymphatic drainage. The channels begin endothelial or as blind sacculations which are also endothelial. They then collect into larger lymph channels running the length of the esophagus (orthogonally to the transverse plane). Flow direction is dictated by paired semilunar valves in these channels. These channels then combine in different areas to enter into respective regional lymph nodes. Drainage occurs in three sections of the esophagus, broken into thirds, with significant interconnections existing between each segment. Drainage into the thoracic duct from the deep cervical lymph nodes is achieved by the drainage of the proximal third segment of the esophagus. Drainage into the superior and posterior mediastinal node is achieved by the lymphatics of the third middle section of the esophagus. Finally, the lymphatics of the distal third-most section of the esophagus ultimately drain into the gastric and celiac lymph nodes.

Nerves

The innervation of the esophagus involves the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, with primary innervation being sourced from the vagus nerve and spinal nerves (from segments T1 to T10) via the thoracic and cervical sympathetic trunk. The vagus nerve is primarily responsible for the parasympathetic motor functions of the esophageal muscles and glands. The thoracic and cervical chain nerves primarily constitute the sympathetic innervation and serve to assist in the constriction of blood vessels, contractions of the UES and LES, muscle wall relaxation, along with gland and peristaltic activity increases. Both nerves allow for sensation, with the vagus nerve detecting pressure which can translate to pain and the sympathetic trunk more directly sensing pain.

Muscles

Approximately the proximal third of the esophagus is primarily composed of skeletal muscle while the distal two-thirds are smooth muscle. The muscle fibers of the esophagus are bi-directional, with the external layer running longitudinally and the internal layer comprising of circular fibers. The internal muscle layer allows for the peristaltic contractions that move boluses down the esophagus and is thicker than the external layer. The thickening and overlapping of the internal muscles at the point of the esophagus below the diaphragm before the stomach comprise the form and function of the LES. Proximally, the cricopharyngeus, thyropharyngeus, and craniocervical muscles comprise the form and function of the UES with the opposing orientations of their respective muscle fibers.

Physiologic Variants

There are not many natural physiological variations amongst esophagus. Variations which are most common are related to size and length. However, there does exist a variety of congenital abnormalities of the esophagus including the following:

- Tracheoesophageal fistula and atresia

- Esophageal stenosis

- Esophageal duplication and duplication cyst

- Esophageal rings

- Esophageal webs

Surgical Considerations

Certain conditions of the esophagus may warrant surgery. Amongst these issues are esophageal cancer, achalasia, tearing, and esophageal varices. Where applicable and possible, laparoscopic surgery is recommended to allow for a minimally invasive approach to the esophagus and faster patient recovery. [7][8]

Clinical Significance

Understanding the esophagus and treating diseases related to the esophagus is of great clinical significance. Most issues of the esophagus, when detected early, can be treated to prevent further damage and even death of the patient. The esophagus is a primary delivery route of food to the stomach, and issues related to this route may affect the nutrition of a patient by not allowing him or her to receive these vital nutrients via this route.

Heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease are very common issues of the esophagus which can affect patients and is highly independent of many factors such as sex, race, and age to name a few. Understanding the function and role the LES has on this issue is of great clinical significance for this reason. These simple, yet common, issues may lead to further esophageal issues such as esophagitis, esophageal cancer, esophageal ulcers, achalasia, and tears of the esophagus.[9]

Media

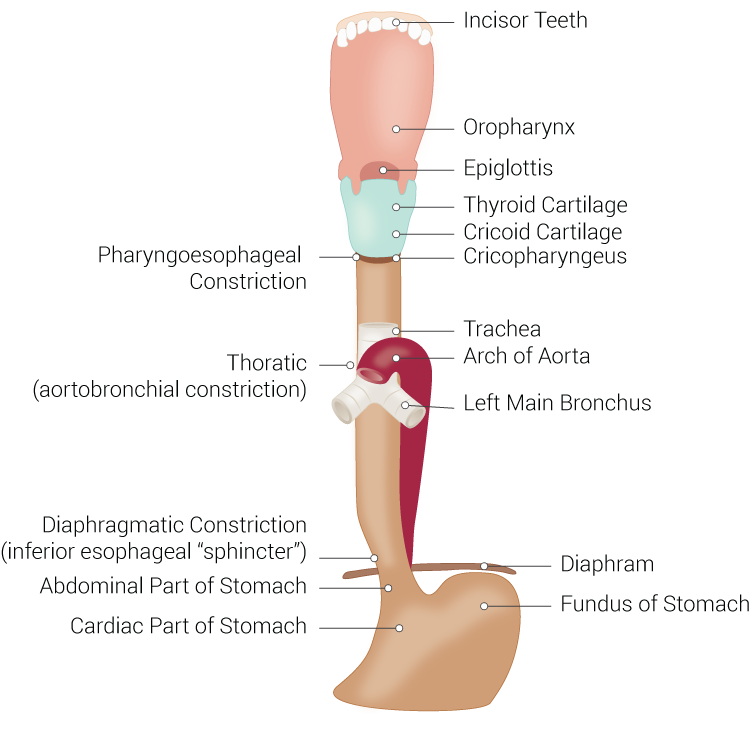

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Digestive and Respiratory Anatomical Structures Connected to the Esophagus. Structures include the esophagus, incisor teeth, oropharynx, epiglottis, thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, cricopharyngeus, trachea, arch of aorta, left main bronchus, diaphragm, fundus of stomach, cardiac part of stomach, abdominal part of stomach, diaphragmatic constriction, inferior esophageal sphincter, thoracic, aortobronchial constriction, and pharyngoesophageal constriction.

Illustration by B Palmer

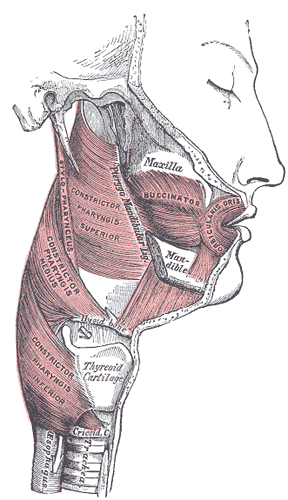

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Muscles of the Cheek and Pharynx. This lateral-view image shows the buccinator, orbicularis oris, and constrictor pharyngis superior, medius, and inferior. The thyroid cartilage, trachea, upper esophagus, stylopharyngeus, maxilla, and mandible are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rizvi S, Wehrle CJ, Law MA. Anatomy, Thorax, Mediastinum Superior and Great Vessels. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137860]

Bains KNS, Kashyap S, Lappin SL. Anatomy, Thorax, Diaphragm. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30137842]

Mahabadi N, Goizueta AA, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Thorax, Lung Pleura And Mediastinum. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085590]

Bardo DME, Biyyam DR, Patel MC, Wong K, van Tassel D, Robison RK. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pediatric mediastinum. Pediatric radiology. 2018 Aug:48(9):1209-1222. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4112-1. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30078043]

Ilahi M, St Lucia K, Ilahi TB. Anatomy, Thorax, Thoracic Duct. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020599]

Fischer NJ, Morreau J, Sugunesegran R, Taghavi K, Mirjalili SA. A reappraisal of pediatric thoracic surface anatomy. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2017 Sep:30(6):788-794. doi: 10.1002/ca.22913. Epub 2017 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 28514496]

Bradley PJ. Symptoms and Signs, Staging and Co-Morbidity of Hypopharyngeal Cancer. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology. 2019:83():15-26. doi: 10.1159/000492304. Epub 2019 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 30943511]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSanghi V, Thota PN. Barrett's esophagus: novel strategies for screening and surveillance. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease. 2019:10():2040622319837851. doi: 10.1177/2040622319837851. Epub 2019 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 30937155]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGonzalez Ayerbe JI, Hauser B, Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Infants and Children: from Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition. 2019 Mar:22(2):107-121. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2019.22.2.107. Epub 2019 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 30899687]