Introduction

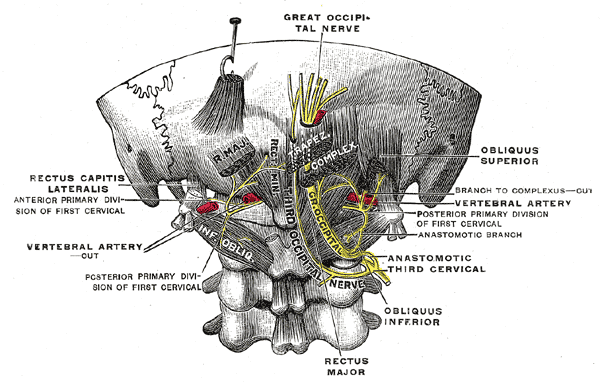

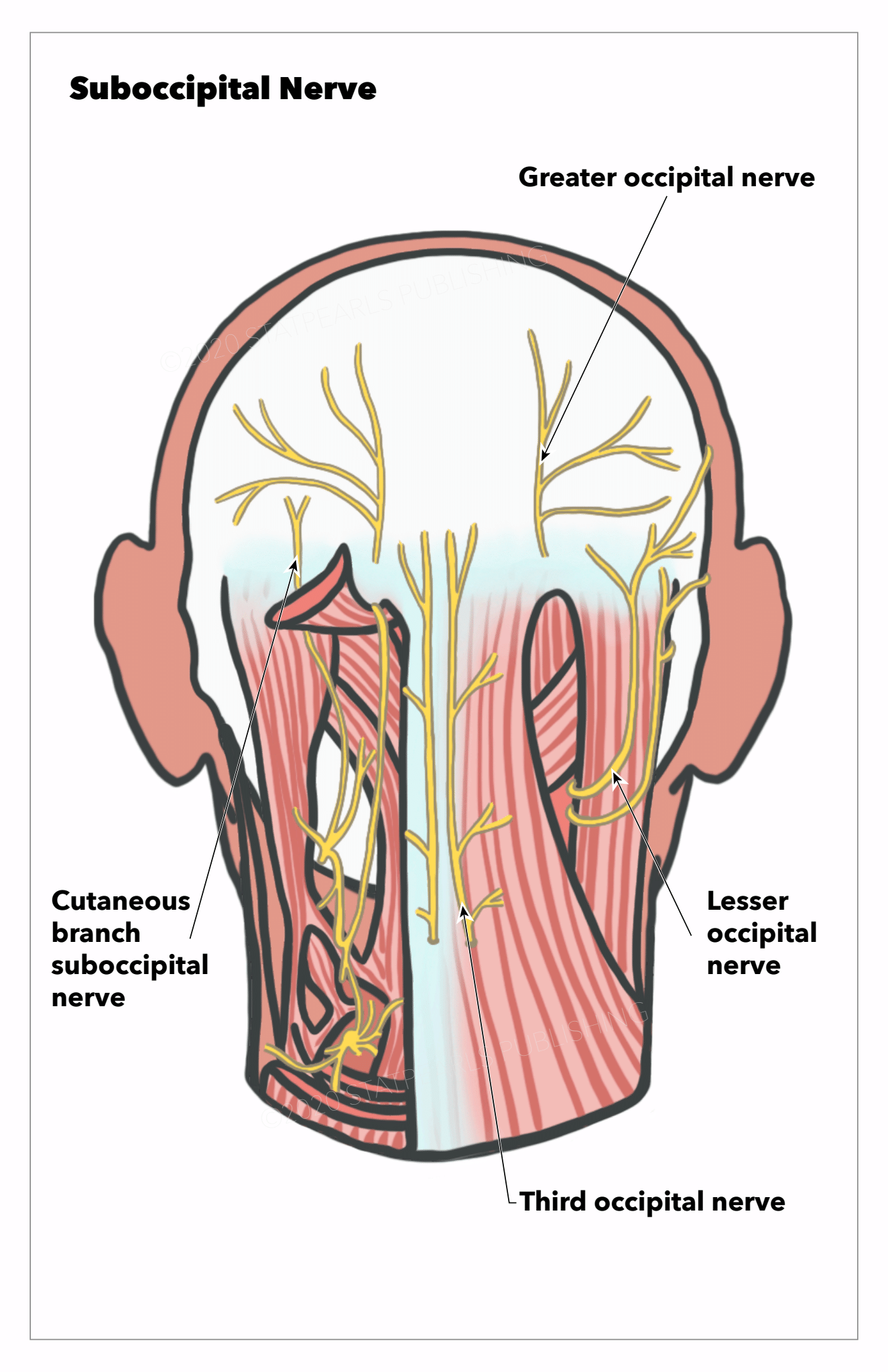

The occipital nerves are a group of nerves that arise from the C2 and C3 spinal nerves.[1][2] They innervate the posterior scalp as far as the vertex and other structures, such as the ear.[2] There are 3 major occipital nerves in the human body: the greater occipital nerve (GON), the lesser (or small) occipital nerve (LON), and the third (or least) occipital nerve (TON). See Image. The Posterior Divisions.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Greater Occipital Nerve

The GON is the biggest purely afferent nerve that arises from the medial division of the dorsal ramus of the C2 spinal nerve. It runs backward between the C1 and C2 vertebrae and traverses between the inferior capitis oblique and semispinalis capitis muscles from underneath the suboccipital triangle.[2] Rarely does the GON travel within the inferior oblique. While traveling to the subcutaneous layer, the GON is found to pierce the semispinalis capitis muscle in most cases and, in some cases, the trapezius and the inferior oblique.[1] This complex involvement with the nearby musculature may make the GON a potential source of nerve compression, entrapment, or irritation. The GON then perforates the aponeurotic fibrous layer of the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid to travel to the scalp and the superior nuchal line.[2] The GON also traverses along the occipital artery after passing through the semispinalis capitis. The GON innervates the skin of the back of the scalp up to the vertex of the skull, the ear, and the skin just above the parotid gland.[2] See Image. Nerves of the Posterior Head and Neck Region.

Lesser Occipital Nerve

The LON originates from the ventral rami of the C2 and C3 spinal nerves and goes to the occipital region along the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[2] It pierces the deep cervical fascia close to the cranium and travels upward. It penetrates the deep cervical fascia near the cranium and goes superiorly above the occiput to innervate the skin and communicate with the GON.[1] The LON has 3 branches: the auricular, mastoid, and occipital. The LON divides into medial and lateral segments between the inion and intermastoid line.[3] The LON innervates the scalp in the lateral region of the head behind the ear and the cranial surface of the ear.[1]

Third Occipital Nerve

The TON is a superficial medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the C3 spinal nerve and is thicker compared to other medial branches.[1] The dorsal ramus of the C3 spinal nerve divides into lateral and medial branches. The medial division is further divided into superficial and deep branches, the superficial division of which is named the TON. The TON travels through the dorsolateral surface of the C2-C3 facet joint.[1] Based on a study by Tubbs et al, the TON was found to send out small branches that travel across the midline and interact with the contralateral TON in 66.7% of patients.[4] The TON also perforates the splenius capitis, trapezius, and semispinalis capitis. It then communicates with the GON and innervates the skin region below the superior nuchal line after innervating the semispinalis capitis. The TON also innervates the facet joint between the C2 and C3 spinal nerves and a portion of the semispinalis capitis.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

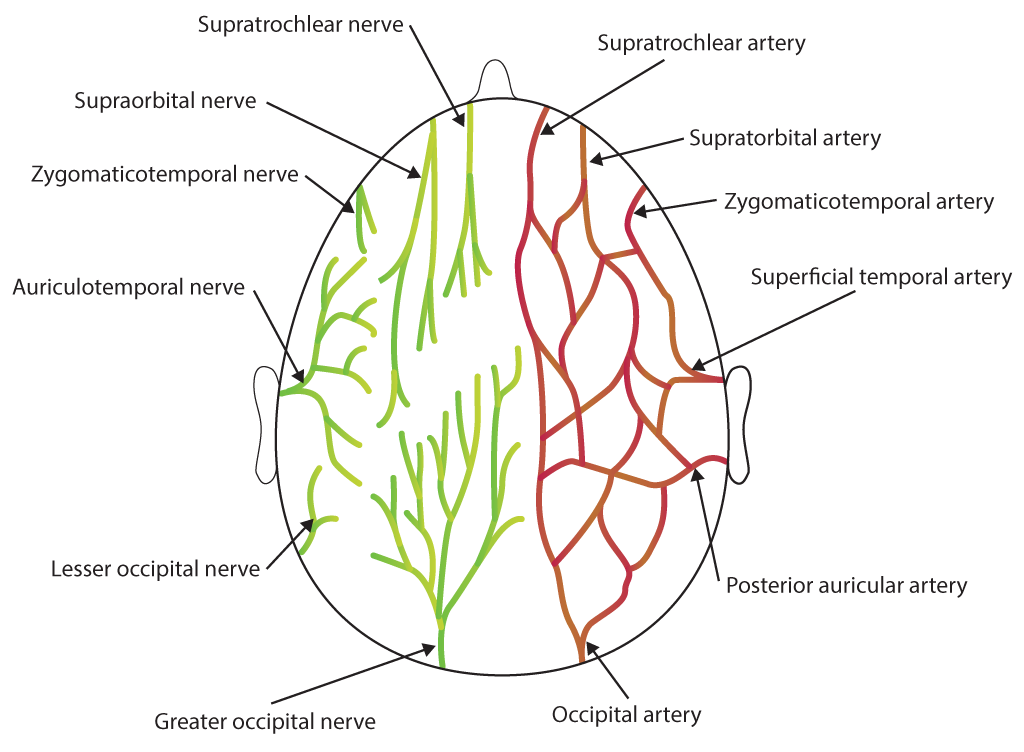

The scalp is highly vascularized and is characterized by having many arterial anastomoses. Most of the blood supply comes from the external carotid arteries.[2] Regarding the occipital region of the scalp, the vascularization is via the occipital artery and the posterior auricular arteries.[5] Within the auriculomastoid sulcus, the posterior auricular artery travels superficially and separates into 3 branches: the mastoid, auricular, and transverse nuchal arteries.[5] The LON is found to be close to the occipital artery. According to Kemp et al, the LON was found to be situated 2.5cm lateral to the occipital artery above the occiput.[2] Also, according to Lee et al, who studied the topography of the LON in 20 sides of 10 heads from fresh cadavers, branches from the occipital artery communicated with the LON in 55% of samples.[6] Among these samples, 45% had the occipital artery crossing the LON at a single location, while 10% of samples had the occipital artery communicating with the LON via a helical intertwining relationship. The researchers also found a fascial band in 20% of samples as a compression point.[6] See Image. Scalp Nerves and Arteries.

The GON is also closely associated with the occipital artery. After the GON perforates the semispinalis capitis, it travels with the medial occipital artery to the nerve.[2] The GON may have a much more intimate relationship than previously thought. According to a study conducted by Janis et al, in which the researchers analyzed the topographic relationship between the GON and occipital artery in fifty samples of 25 posterior necks and scalps from cadavers, the GON and occipital artery were found to cross each other in 54% of samples.[7] Among samples with an intersection between the GON and the occipital artery, these crossings could differ from intersecting at a single point (29.6%) to intertwining helically (70.4%). These crossings were usually discovered in the tunnel of the trapezius caudal to the occipital protuberance but were also present above the occipitalis.[7] These findings may be useful for migraine patients, as many of these patients report having pulsatile symptoms, and their headaches may contain a vascular component. Many researchers have proposed that the GON and occipital artery intersections may be responsible for these symptoms.[7] Furthermore, another study by Shimizu et al discovered the occipital artery. GON intersected in the nuchal subcutaneous layer, and the GON was always more superficial to the occipital artery at the point of intersection.[8] They postulated that the intimate relationship between the GON and the occipital artery might contribute to occipital neuralgia.[8]

Nerves

As mentioned previously, the GON arises from the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the C2 spinal nerve and innervates the skin of the back of the scalp up to the vertex of the skull, the ear, and the skin just above the parotid gland.[2] When the GON is over the occiput, it communicates with the LON and the TON laterally. The LON comes from the ventral rami of the C2 and C3 spinal nerves and provides innervation to the scalp in the lateral region of the head behind the ear.[2] The LON also transmits a branch to the GON as it goes above the occiput near the cranium.[2] It also communicates with the mastoid division of the greater auricular nerve. The TON originates from the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the C3 spinal nerve. It innervates the facet joint between the C2 and C3 spinal nerves and a portion of the semispinalis capitis.[2] Its cutaneous division also innervates the skin below the occiput. The TON also communicates with the GON and innervates the region of the skin below the superior nuchal line.[2]

Muscles

Greater Occipital Nerve

As stated previously, the GON traverses between the inferior capitis oblique and semispinalis capitis muscles from underneath the suboccipital triangle.[2] Rarely does the GON travel within the inferior oblique. While traveling to the subcutaneous layer, the GON is found to pierce the semispinalis capitis muscle in most cases and, in some cases, the trapezius and the inferior oblique.[1] For the treatment of GON entrapment neuropathy, the regions where the GON traverses between the atlas and the axis, the GON courses between the obliquus capitis inferior and semispinalis capitis, or the GON perforates the semispinalis capitis and the trapezius, which are potential areas of GON irritation and entrapment.[9] These zones could be affected by other medical issues, such as whiplash injuries and posture imbalances, and could serve as possible origins of ON.[9] However, the GON has many physiological variants discussed in the following section.

Lesser Occipital Nerve

Regarding the LON, the area where the LON traverses from behind the sternocleidomastoid, the area where the LON ascends along the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid, and the area where the LON intersects with the nuchal line have been found to serve as potential compression points.[10] This topic covers the physiological variants of the LON in the following section.

Physiologic Variants

Greater Occipital Nerve

As stated previously, for the GON, the region where it traverses between the atlas and the axis, the area where it courses between the obliquus capitis inferior and semispinalis capitis or the area where it perforates the semispinalis capitis and the trapezius are potential areas of GON irritation and entrapment and could likely lead to occipital neuralgia.[9] However, many studies had different results regarding the prevalence and descriptions of these locations. For instance, in 20 autopsy cases, Bovim et al discovered the GON perforated the trapezius in 45% of samples, the semispinalis capitis in 90% of samples, and the inferior oblique in 7.5% of samples.[11] They also stated the GON did not pass through the trapezius in all cases but appeared from an opening above the aponeurotic fibrous layer of the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid.[11] In another study by Ducic et al, among 125 individuals, the GON passed through the semispinalis capitis muscle in 98.5% of cases.[12] The remaining cases were divided by semispinalis capitis fibers or were within the trapezius. The nerves were also asymmetric on both sides in 43.9% of individuals.[12]

In another study by Tubbs et al, among samples from 12 adult cadavers, the GON perforated the trapezius in 16.7% of cases and the aponeurosis in 83.3% of cases. In another study by Junewicz et al, among 272 patients who had GON decompression surgery, the GON was discovered to perforate the semispinalis in all patients bilaterally.[3] About 7.4% of patients had multiple branches of the GON, and 3.7% of subjects had blood vessels or muscles within these branches.[3] Finally, in a study by Won et al, among 56 specimens from cadavers, 62.5% of the samples had the GON perforating the fascia between the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid. In contrast, 37.5% of the samples had the GON passing through the trapezius.[9] Physicians should note these anatomic variations to understand better the topography of the GON and the nearby vasculature.

Lesser Occipital Nerve

The LON was mainly found to be at the posterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. However, reports exist showing some anatomic variations of the LON. For instance, Madhavi et al reported a bilateral triplication of the LON in an adult cadaver.[13] One of the LONs originated from a nerve close to the trapezius that came from the supraclavicular nerve. Another LON traversed through the posterior triangle and the trapezius and innervated the scalp's neck, auricle, and posterior area.[13] The authors concluded these findings might be relevant to patients with cervicogenic headaches because some may experience pain from neck movement.[13] Previous studies also reported duplication of the LON. There are also reports of the LON passing through the occipital region of the posterior triangle, even though this phenomenon was rare.[14] Also, as mentioned previously, Lee et al reported that among samples where branches from the occipital artery contacted the LON, 45% of samples had the occipital artery crossing the LON at a single location, while 10% of samples had the occipital artery communicating with the LON via a helical intertwining relationship.[6] A fascial band also appeared as a compression point in 20% of samples.[6] Peled et al also reported similar results. However, they also noted a lot of variation regarding the branching of the LON.[10] Physicians should consider these results to ensure patients who receive surgical treatment of the LON receive maximum benefit.

Surgical Considerations

The GON, LON, and TON are commonly associated with occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic headaches, and migraine headaches.[1] Occipital neuralgia is a type of headache characterized by paroxysmal stabbing pain in the posterior area of the scalp.[1] Although there is a wide range of treatment options for occipital neuralgia, there is currently no consensus among medical practitioners about which method is superior. Occipital nerve block, pulsed or thermal radiofrequency ablation, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation are minimally invasive treatments used to treat occipital neuralgia, migraines, cluster headaches, and associated features of cervicogenic headaches.[2] Other surgical treatments used to treat this disease include dorsal rhizotomy, occipital neurectomy, and microvascular decompression.[2] A review of these treatments follows.

Occipital Nerve Block

GON blocks are frequently used to treat migraine headaches and occipital neuralgia. A small dose of local anesthetic combined with corticosteroids is injected halfway on the nuchal line between the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process and above the occipital ridge.[1] The occipital artery is the most reliable anatomical landmark because the nerve appears to align with this artery. To increase the chances that the surgery is successful, the potential areas for GON, LON, and TON entrapment and compression, as previously mentioned, must be considered.[2] For GON blocks, among 562 patients with migraines who had GON blocks, Allen et al reported 58% of patients had reduced their baseline pain scores by more than 50%, and these results were consistent regardless of age, prior treatments, or sex.[15] In another study conducted by Juskys et al, among 44 patients with occipital neuralgia who received treatment with an occipital nerve block, 95.45% of patients were comfortable with the pain for at least 6 months, and only 16.67% of patients needed analgesics to cope with the pain after 6 months.[16] Although controlled, blinded studies are limited, and there is currently no standardization of the procedure, nerve blocks, particularly GON blocks, have demonstrated effectiveness in treating migraines and ON.

Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF) or Thermal Radiofrequency Ablation (TRFA)

Regarding the GON, LON, and TON, PRF may decrease pain by generating a low-intensity electrical field around sensory nerves that hinder the operation of the A-delta and C fibers in the long run.[1] However, the reports published concerning PRF treatment of occipital neuralgia were small, observational cohort studies or case reports. For instance, Kim et al reported successful attempts at performing ultrasound-guided PRF on 2 male patients with headaches in the occipital region.[17] In another study conducted by Cohen et al, among 81 patients with occipital neuralgia who either received PRF or local anesthetic, the PRF group had, on average, a greater decrease in occipital pain within 6 weeks, which lasted through the follow-up at 6 months.[18] TRFA can render long-term analgesia but introduces several potential risks, including dysesthesia, anesthesia dolorosa, hypesthesia, and the development of a neuroma. According to a study by Hoffman et al., 50 patients with occipital neuralgia who received GON and LON TRFA reported, on average, 76.3% pain relief lasting 6.5 months.[19] More studies regarding the efficacy of PRF or TRFA should be necessary for patients with occipital neuralgia.

Occipital Nerve Stimulation/Neuromodulation

Occipital nerve stimulation has been used to relieve severe pain caused by occipital neuralgia when conservative medical treatments and block procedures are ineffective. It involves placing nerve stimulator leads obliquely or horizontally near the bottom of the skull across from the GON location.[20] Some risks of this procedure include surgical infection and movement of the lead or generator after the operation. Based on a study by Johnstone et al, among 8 patients with occipital neuralgia who received optic nerve stimulation, 7 of them were implanted with a permanent lead once they had a 50% reduction in pain.[21] This type of procedure has been used for patients with primary headaches, such as migraines and cluster headaches, and patients with secondary headaches, such as occipital neuralgia and cervicogenic headaches.[22]

Ultrasound-guided Cryoneurolysis of the GON

Cryoneurolysis of the GON has been used to manage the symptoms of patients with ON. Even though there is limited evidence of this technique's efficacy, a previous study by Kastler et al, who performed 7 cryo-neurolysis procedures of the GON in 6 patients with occipital neuralgia, demonstrated the technique helped alleviate pain for 3 months in 5 of the patients.[23]

Dorsal Rhizotomy

Another possible treatment option for occipital neuralgia is dorsal rhizotomy of the C1 to C3 spinal nerves, in which the ventrolateral margin of the C1 to C3 rootlets become separated at the entry points.[2] Although there is little risk for patients to have complications, a complete upper cervical rhizotomy leads to a loss of sensation in the scalp, and the procedure may not always relieve the pain. Also, the amount of pain that is alleviated may reduce over time.[2] According to a study by Grande et al, among 75 patients with occipital neuralgia who had dorsal rhizotomy, 35 patients reported having full relief of pain, while 11 patients had partial pain relief, and 7 patients had no pain relief at all. Twenty-one patients stated their activity levels were enhanced, while 5 had decreased activity levels after surgery.[24] In another study by Dubuisson, among 11 patients with occipital neuralgia who had 14 partial dorsal rhizotomies, pain near the GON decreased, and pain relief was regarded as good or excellent among 10 of the procedures performed.[25] More studies regarding the efficacy of dorsal rhizotomy are necessary for patients with occipital neuralgia.

Peripheral Neurectomy

Peripheral neurectomy has been suggested to be an effective surgical technique for patients with occipital neuralgia, providing effective pain relief in most patients. However, few studies have evaluated the efficacy of this treatment. Thus, more studies are required to fully assess the efficacy and possible complications of performing peripheral neurectomies among patients with ON.

Surgical Decompression

Botulinum toxin could potentially offer pain relief to patients with ON. Within presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals, the toxin attaches to high-affinity recognition sites and blocks acetylcholine delivery.[2] Surgical decompression is another option, and a previous study stated GON decompression was 62% effective in reducing pain from occipital neuralgia.[2] However, a large number of patients may be refractory to surgical intervention. Jose et al also reported that among eleven patients with refractory occipital neuralgia who had GON surgical decompression, the average number of pain episodes decreased from 17.1 to 4.1 episodes every month. The average pain intensity also decreased significantly.[26] Three patients also had complete removal of pain, and only 2 patients did not experience significant improvement.[26] For GON microsurgical decompression, in a previous study investigating the efficacy of performing the procedure among 76 patients with headache symptoms, 89.5% had their symptoms resolved. In contrast, 3.9% had a recurrence of their symptoms.[27] Even though all of the patients had GON hypoesthesia, they recuperated 1 to 6 months after the surgery. These results demonstrated microsurgical decompression might be an effective way to treat patients with occipital neuralgia.[27] In addition to the surgical considerations above, physicians should take into account any anatomic details or variations for the GON, LON, and TON that were mentioned previously to reduce the risk of undesirable postoperative outcomes and help maximize the benefits for patients who are receiving treatment with regards to these occipital nerves.

Clinical Significance

Because the GON, LON, and TON play significant roles in the innervation of the scalp, they are often associated with occipital neuralgia. Based on the International Headache Society, patients with occipital neuralgia have stabbing pain in the GON and LON dermatomes that originates from GON or LON compression and spans from the suboccipital area to the upper portion of the neck, the area behind the eyes, and the posterior region of the head.[1] Patients may also experience tenderness, hypoesthesia, or dysesthesia in the same locations. Tenderness in the affected areas and temporary pain relief with local anesthetic nerve blocks confirm the diagnosis.[1] Because occipital neuralgia is associated with cranial nerves 8, 9, and 10, patients may experience nausea, dizziness, vision impairment, and congestion in the nose.[1] However, it is common to confuse occipital neuralgia with other diseases unless physicians notice other distinguishing factors. For instance, physicians must distinguish occipital neuralgia from infections, tumors, and congenital abnormalities, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation. They may confuse occipital neuralgia with migraines, cluster headaches, tension headaches, or hemicranial continua.[1] Physicians must also distinguish occipital neuralgia from cervicogenic headaches because occipital neuralgia is defined as neuralgia in the occipital nerves. In contrast, cervicogenic headaches arise from referred pain within atlantoaxial or upper zygapophyseal joints or trigger points inside the neck muscles.[1] Anticonvulsants, massage, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and muscle relaxants are usually first-line treatments.[28] If patients do not respond clinically to these treatments or minimally invasive procedures, such as PRF, other invasive treatments, such as nerve blocks, may be considered. Some conservative treatment options consist of correcting posture and reducing muscle pain.[1] However, many studies have yielded variable results regarding the efficacy of these treatments. There is a limited number of well-designed, randomized, case-control studies regarding the efficacies of these invasive treatments.[1]

Additionally, GON blocks have been used to treat other forms of headaches, such as migraines, cluster headaches, and cervicogenic headaches.[29] GON blocks appear to alleviate pain for a variable, short period. For instance, Lambru et al reported that among 83 patients with cluster headaches, GON blocks resulted in an average pain alleviation period of 21 days.[30] In another study by Afridi et al, among 26 out of 57 nerve blocks in 54 patients with migraines, GON blocks led to an average pain alleviation period of 30 days. For patients with cluster headaches, GON blocks led to an average pain alleviation period of 21 days.[31] RFA has also been used to provide long-term relief; however, RFA may cause certain complications, such as post-denervation neuralgia.[29] For cervicogenic headaches, GON and LON nerve blocks are some conventional treatments. Patients with whiplash injuries may also suffer from third occipital headaches. Whiplash injuries are often associated with motor vehicle accidents, and patients with these injuries may have stiffness and pain in the neck, paresthesias, memory problems, and psychological pain.[32] Previous studies have demonstrated radiofrequency neurotomy may provide complete pain relief for patients with TON headaches. However, the procedure has some side effects, such as temporary ataxia, dysesthesia, and numbness.[33] Moreover, the process has to be repeated once the coagulated nerve recovers.[33]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Scalp Nerves and Arteries. Illustration includes supratrochlear nerve, supraorbital nerve, zygomaticotemporal nerve, auriculotemporal nerve, lesser occipital nerve, greater occipital nerve, supratrochlear artery, supratorbital artery, zygomaticotemporal artery, superficial temporal artery, posterior auricular artery, and occipital artery.

Contributed by Bryan Parker

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Choi I, Jeon SR. Neuralgias of the Head: Occipital Neuralgia. Journal of Korean medical science. 2016 Apr:31(4):479-88. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.4.479. Epub 2016 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 27051229]

Kemp WJ 3rd, Tubbs RS, Cohen-Gadol AA. The innervation of the scalp: A comprehensive review including anatomy, pathology, and neurosurgical correlates. Surgical neurology international. 2011:2():178. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.90699. Epub 2011 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 22276233]

Tubbs RS, Salter EG, Wellons JC, Blount JP, Oakes WJ. Landmarks for the identification of the cutaneous nerves of the occiput and nuchal regions. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2007 Apr:20(3):235-8 [PubMed PMID: 16944523]

Tubbs RS, Mortazavi MM, Loukas M, D'Antoni AV, Shoja MM, Chern JJ, Cohen-Gadol AA. Anatomical study of the third occipital nerve and its potential role in occipital headache/neck pain following midline dissections of the craniocervical junction. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2011 Jul:15(1):71-5. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.SPINE10854. Epub 2011 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 21495817]

Touré G, Méningaud JP, Vacher C. Arterial vascularization of occipital scalp: mapping of vascular cutaneous territories and surgical applications. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2010 Oct:32(8):739-43. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0673-x. Epub 2010 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 20499067]

Lee M, Brown M, Chepla K, Okada H, Gatherwright J, Totonchi A, Alleyne B, Zwiebel S, Kurlander D, Guyuron B. An anatomical study of the lesser occipital nerve and its potential compression points: implications for surgical treatment of migraine headaches. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Dec:132(6):1551-1556. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80721. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24005368]

Janis JE, Hatef DA, Reece EM, McCluskey PD, Schaub TA, Guyuron B. Neurovascular compression of the greater occipital nerve: implications for migraine headaches. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Dec:126(6):1996-2001. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8c6b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21124138]

Shimizu S, Oka H, Osawa S, Fukushima Y, Utsuki S, Tanaka R, Fujii K. Can proximity of the occipital artery to the greater occipital nerve act as a cause of idiopathic greater occipital neuralgia? An anatomical and histological evaluation of the artery-nerve relationship. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007 Jun:119(7):2029-2034. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000260588.33902.23. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17519696]

Won HJ, Ji HJ, Song JK, Kim YD, Won HS. Topographical study of the trapezius muscle, greater occipital nerve, and occipital artery for facilitating blockade of the greater occipital nerve. PloS one. 2018:13(8):e0202448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202448. Epub 2018 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 30110386]

Peled ZM, Pietramaggiori G, Scherer S. Anatomic and Compression Topography of the Lesser Occipital Nerve. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2016 Mar:4(3):e639. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000654. Epub 2016 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 27257569]

Bovim G, Bonamico L, Fredriksen TA, Lindboe CF, Stolt-Nielsen A, Sjaastad O. Topographic variations in the peripheral course of the greater occipital nerve. Autopsy study with clinical correlations. Spine. 1991 Apr:16(4):475-8 [PubMed PMID: 2047922]

Ducic I, Moriarty M, Al-Attar A. Anatomical variations of the occipital nerves: implications for the treatment of chronic headaches. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Mar:123(3):859-863. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199f080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19319048]

Madhavi C, Holla SJ. Triplication of the lesser occipital nerve. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2004 Nov:17(8):667-71 [PubMed PMID: 15495173]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRavindra S S, Sirasanagandla SR, Nayak SB, Rao Kg M, Patil J. An Anatomical Variation of the Lesser Occipital Nerve in the "Carefree part" of the Posterior Triangle. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2014 Apr:8(4):AD05-6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7423.4276. Epub 2014 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 24959430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAllen SM, Mookadam F, Cha SS, Freeman JA, Starling AJ, Mookadam M. Greater Occipital Nerve Block for Acute Treatment of Migraine Headache: A Large Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2018 Mar-Apr:31(2):211-218. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29535237]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJuškys R, Šustickas G. Effectiveness of treatment of occipital neuralgia using the nerve block technique: a prospective analysis of 44 patients. Acta medica Lituanica. 2018:25(2):53-60. doi: 10.6001/actamedica.v25i2.3757. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30210238]

Kim ED, Kim YH, Park CM, Kwak JA, Moon DE. Ultrasound-guided Pulsed Radiofrequency of the Third Occipital Nerve. The Korean journal of pain. 2013 Apr:26(2):186-90. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.186. Epub 2013 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 23614084]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen SP, Peterlin BL, Fulton L, Neely ET, Kurihara C, Gupta A, Mali J, Fu DC, Jacobs MB, Plunkett AR, Verdun AJ, Stojanovic MP, Hanling S, Constantinescu O, White RL, McLean BC, Pasquina PF, Zhao Z. Randomized, double-blind, comparative-effectiveness study comparing pulsed radiofrequency to steroid injections for occipital neuralgia or migraine with occipital nerve tenderness. Pain. 2015 Dec:156(12):2585-2594. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000373. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26447705]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHoffman LM, Abd-Elsayed A, Burroughs TJ, Sachdeva H. Treatment of Occipital Neuralgia by Thermal Radiofrequency Ablation. Ochsner journal. 2018 Fall:18(3):209-214. doi: 10.31486/toj.17.0104. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30275783]

Djavaherian DM, Guthmiller KB. Occipital Neuralgia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855865]

Johnstone CS, Sundaraj R. Occipital nerve stimulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia-eight case studies. Neuromodulation : journal of the International Neuromodulation Society. 2006 Jan:9(1):41-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2006.00041.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22151592]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLambru G, Matharu MS. Occipital nerve stimulation in primary headache syndromes. Therapeutic advances in neurological disorders. 2012 Jan:5(1):57-67. doi: 10.1177/1756285611420903. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22276076]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKastler A, Attyé A, Maindet C, Nicot B, Gay E, Kastler B, Krainik A. Greater occipital nerve cryoneurolysis in the management of intractable occipital neuralgia. Journal of neuroradiology = Journal de neuroradiologie. 2018 Oct:45(6):386-390. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2017.11.002. Epub 2017 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 29273528]

Gande AV, Chivukula S, Moossy JJ, Rothfus W, Agarwal V, Horowitz MB, Gardner PA. Long-term outcomes of intradural cervical dorsal root rhizotomy for refractory occipital neuralgia. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Jul:125(1):102-10. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.JNS142772. Epub 2015 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 26684782]

Dubuisson D. Treatment of occipital neuralgia by partial posterior rhizotomy at C1-3. Journal of neurosurgery. 1995 Apr:82(4):581-6 [PubMed PMID: 7897518]

Jose A, Nagori SA, Chattopadhyay PK, Roychoudhury A. Greater Occipital Nerve Decompression for Occipital Neuralgia. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Jul:29(5):e518-e521. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004549. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29762321]

Li F, Ma Y, Zou J, Li Y, Wang B, Huang H, Wang Q, Li L. Micro-surgical decompression for greater occipital neuralgia. Turkish neurosurgery. 2012:22(4):427-9. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.5234-11.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22843458]

Dougherty C. Occipital neuralgia. Current pain and headache reports. 2014 May:18(5):411. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0411-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24737457]

Kim DD, Sibai N. Prolongation of greater occipital neural blockade with 10% lidocaine neurolysis: a case series of a new technique. Journal of pain research. 2016:9():721-725 [PubMed PMID: 27729811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLambru G, Abu Bakar N, Stahlhut L, McCulloch S, Miller S, Shanahan P, Matharu MS. Greater occipital nerve blocks in chronic cluster headache: a prospective open-label study. European journal of neurology. 2014 Feb:21(2):338-43. doi: 10.1111/ene.12321. Epub 2013 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 24313966]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAfridi SK, Shields KG, Bhola R, Goadsby PJ. Greater occipital nerve injection in primary headache syndromes--prolonged effects from a single injection. Pain. 2006 May:122(1-2):126-9 [PubMed PMID: 16527404]

Yadla S, Ratliff JK, Harrop JS. Whiplash: diagnosis, treatment, and associated injuries. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Mar:1(1):65-8. doi: 10.1007/s12178-007-9008-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19468901]

Govind J, King W, Bailey B, Bogduk N. Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of third occipital headache. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2003 Jan:74(1):88-93 [PubMed PMID: 12486273]