Introduction

A variety of factors guide the evaluation and management of burns. First is the type of burn, such as thermal, chemical, electrical, or radiation. Second is the extent of the burn, usually expressed as the percentage of total body surface area (%TBSA) involved. Next is the depth of the burn described as superficial (first degree), partial (second degree) or full thickness (third degree). Finally, other factors include specific patient characteristics like the age of the patient (< 10 or > 50 years old), other medical or health problems, if there are specialized locations of the burn (face, eyes, ears, nose, hands, feet, and perineum); and if there are any associated injuries, particularly smoke inhalation and other traumatic injuries.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Burns may be caused by:

- Abuse

- Chemicals such as strong acids, lye, paint thinner, or gasoline

- Electric currents

- Fire

- Hot liquid

- Hot metal, glass, or other objects

- Steam

- Radiation from X-rays

- Sunlight or ultraviolet light

Epidemiology

Approximately 86% of burns are caused by thermal injury, while about 4% are electrical and 3% are chemical. Flame and scald burns are the leading cause of burns in children and adults. More adults are injured with flame burns, while children younger than five years old are more often injured with scald burns. Burn injuries more commonly affect people of low and middle income and people in low-income countries.

Pathophysiology

Burns are injuries of the skin involving the two main layers - the thin outer epidermis and the thicker, deeper dermis. There are various types of burns. Chemical burns are divided into acid or alkali burns. Alkali burns tend to be more severe, causing more penetration deeper into the skin by liquefying the skin (liquefaction necrosis). Acid burns penetrate less because they cause a coagulation injury (coagulation necrosis). Electrical burns can be deceiving with small entry and exit wounds, however, there may be extensive internal organ injury or associated traumatic injuries. Thermal burns are the most common type of burn. Most burns are small and superficial, causing only local injuries. However, burns can be larger and deeper, and patients can also have a systemic response to severe burns.[5][6]

History and Physical

Because most burns are small and classified as minor, the history and physical can proceed as usual. If the patient appears to have burns classified as severe, then the approach should be like that of a major trauma patient (see Burns, Resuscitation, and Management chapter). Key factors in the history include the type of burn, possible inhalation injury, and possible associated traumatic injuries. If possible, ask prehospital emergency services providers if the patient had prolonged smoke exposure (consider carbon monoxide poisoning, cyanide poisoning, lung injury) or might have other injuries from explosions, falls, or jumping to safety. Examination of the burn can be done in the patient's secondary survey. The patient's clothing should be removed, and the patient should be examined from head to toe in a warm room.

Evaluation

The major factors to consider when evaluating the burned skin are the extent of the burns (usually calculated by the percentage of total body surface area (% TBSA) burned) and the estimated depth of the burns (superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness).[7][8][9][10][11]

Extent of the Burn

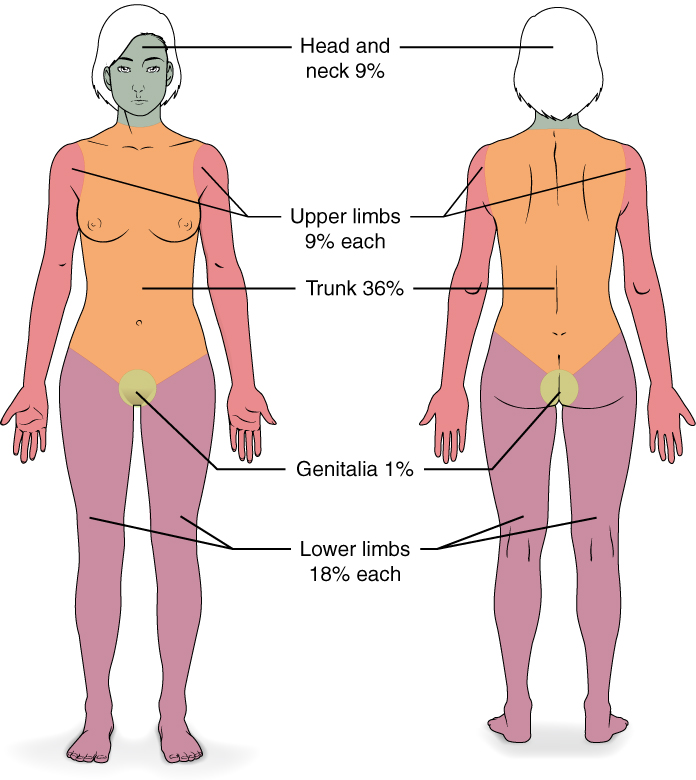

Several methods are available to estimate the percentage of total body surface area burned.

- Rule of Nines - The head represents 9%, each arm is 9%, the anterior chest and abdomen are 18%, the posterior chest and back are 18%, each leg is 18%, and the perineum is 1%. For children, the head is 18%, and the legs are 13.5% each.

- Lund and Browder Chart—This is a more accurate method, especially in children, where each arm is 10%, the anterior and posterior trunks are each 13%, and the percentage calculated for the head and legs varies based on the patient's age.

- Palmar Surface - For small burns, the patient's palm surface (excluding the fingers) represents approximately 0.5% of their body surface area, and the hand surface (including the palm and fingers) represents about 1% of their body surface area.

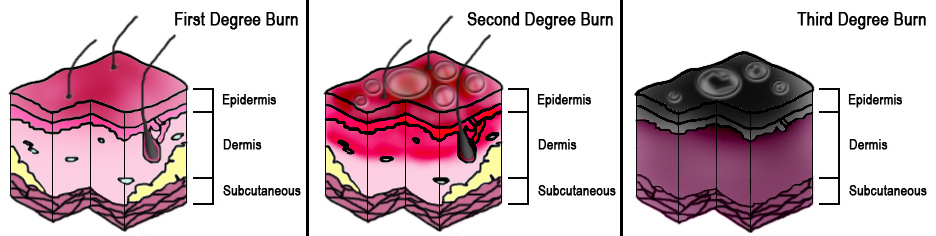

Depth of the Burn

Burn depth is classified into one of three types based on how deeply into the epidermis or dermis the injury might extend.

- Superficial burns (first degree) involve only the epidermis and are warm, painful, red, soft, and blanch when touched. Usually, there is no blistering. A typical example is a sunburn.

- Partial-thickness burns (second-degree) extend through the epidermis and into the dermis. The depth into the dermis can vary (superficial or deep dermis). These burns are typically very painful, red, blistered, moist, soft, and blanch when touched. Examples include burns from hot surfaces, hot liquids, or flames.

- Full-thickness burns (third-degree) extend through both the epidermis and dermis and into the subcutaneous fat or deeper. These burns have little or no pain, can be white, brown, or charred, and feel firm and leathery to palpation with no blanching. These occur from a flame, hot liquids, or superheated gasses.

When calculating the extent of burns, only partial-thickness and full-thickness burns are considered, and superficial burns are excluded.

Treatment / Management

The American Burn Association recommends burn center referrals for patients with:

- partial thickness burns greater than 10% total body surface area

- full-thickness burns

- burns of the face, hands, feet, genitalia, or major joints

- chemical burns, electrical, or lighting strike injuries

- significant inhalation injuries

- burns in patients with multiple medical disorders

- burns in patients with associated traumatic injuries

Patients transferred to burn centers do not need extensive debridement or topical antibiotics before transfer. Whether transferring or referring to a burn center, you should contact them before beginning extensive local burn care treatments.[12][13](B3)

Minor burns that one plans to treat can be approached using the “C” of burn care:

- Cooling - Small areas of burn can be cooled with tap water or saline solution to prevent progression of burning and to reduce pain.

- Cleaning – Mild soap and water or mild antibacterial wash. Debate continues over the best treatment for blisters. However, large blisters are debrided, while small blisters and blisters involving the palms or soles are left intact.

- Covering – Topical antibiotic ointments or creams with absorbent or specialized burn dressing materials are commonly used.

- Comfort – Over-the-counter pain medications or prescription pain medications when needed. Splints can also provide support and comfort for certain burned areas.

For burns classified as severe (> 20% TBSA), fluid resuscitation should be initiated to maintain urine output > 0.5 mL/kg/hour. One commonly used fluid resuscitation formula is the Parkland formula. The total amount of fluid to be given during the initial 24 hours = 4 ml of LR × patient’s weight (kg) × % TBSA. Half the calculated amount is administered during the first eight hours, beginning when the patient is initially burned. For example, if a 70 kg patient has a 30% TBSA partial thickness burn, they will need 8400 mL Lactated Ringer solution in the first 24 hours with 4200 mL of that total in the first 8 hours [(4 mL) × (70 kg) × (30% TBSA) = 8,400 mL LR]. Remember that the fluid resuscitation formula for burns is only an estimate, and the patient may need more or less fluid based on vital signs, urine output, other injuries, or other medical conditions (see Burns, Resuscitation, and Management for discussion of the management of severely burned patients).

In patients with moderate to severe flame burns and with suspicion for inhalation injury, carboxyhemoglobin levels should be checked, and patients should be placed on high-flow oxygen until carbon monoxide poisoning is ruled out. If carbon monoxide poisoning is confirmed, continue treatment with high-flow oxygen and consider hyperbaric oxygen in select cases (see Hyperbaric, Carbon Monoxide Toxicity chapter). Cyanide poisoning can also occur from smoke inhalation and can be treated with hydroxocobalamin (see Inhalation Injury chapter).

Differential Diagnosis

There are two main differential diagnoses of thermal burn injuries, and these should always be ruled out. These are:

- Cellulitis

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of burn patients is with an interprofessional team that consists of a surgeon, intensivist, burn specialist, dietitian, physical therapist, nurses, wound care specialists, pulmonologist, and plastic surgeon. Burn patients are best looked after by a burn team in a specialized center. The key is to prevent complications and restore functionality. The outcomes of burn patients depend on the degree and extent of the burn. Most second and third-degree burns require prolonged admission, and recovery is slow. Because cosmesis is significantly altered in burn patients, a mental health consult should be made prior to discharge.[14][15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mehta M, Tudor GJ. Parkland Formula. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725875]

Sahin C, Kaplan P, Ozturk S, Alpar S, Karagoz H. Treatment of partial-thickness burns with a tulle-gras dressing and a hydrophilic polyurethane membrane: a comparative study. Journal of wound care. 2019 Jan 2:28(1):24-28. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2019.28.1.24. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30625045]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEyvaz K, Kement M, Balin S, Acar H, Kündeş F, Karaoz A, Civil O, Eser M, Kaptanoglu L, Vural S, Bildik N. Clinical evaluation of negative-pressure wound therapy in the management of electrical burns. Ulusal travma ve acil cerrahi dergisi = Turkish journal of trauma & emergency surgery : TJTES. 2018 Sep:24(5):456-461. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2018.80439. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30394501]

Wu YT, Chen KH, Ban SL, Tung KY, Chen LR. Evaluation of leap motion control for hand rehabilitation in burn patients: An experience in the dust explosion disaster in Formosa Fun Coast. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2019 Feb:45(1):157-164. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.08.001. Epub 2018 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30322737]

Stiles K. Emergency management of burns: part 2. Emergency nurse : the journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association. 2018 Jul:26(2):36-41 [PubMed PMID: 30095874]

Stiles K. Emergency management of burns: part 2. Emergency nurse : the journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association. 2018 Jul 3:():. doi: 10.7748/en.2018.e1815. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 29969203]

Grammatikopoulou MG, Theodoridis X, Gkiouras K, Stamouli EM, Mavrantoni ME, Dardavessis T, Bogdanos DP. AGREEing on Guidelines for Nutrition Management of Adult Severe Burn Patients. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2019 May:43(4):490-496. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1452. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30320409]

Watson C, Troynikov O, Lingard H. Design considerations for low-level risk personal protective clothing: a review. Industrial health. 2019 Jun 4:57(3):306-325. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2018-0040. Epub 2018 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30089764]

Johnson SP, Chung KC. Outcomes Assessment After Hand Burns. Hand clinics. 2017 May:33(2):389-397. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2016.12.011. Epub 2017 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 28363303]

Beltran SL, Vilela RAG, de Almeida IM. Challenging the immediate causes: A work accident investigation in an oil refinery using organizational analysis. Work (Reading, Mass.). 2018:59(4):617-636. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182702. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29733046]

Devinck F, Deveaux C, Bennis Y, Deken-Delannoy V, Jeanne M, Martinot-Duquennoy V, Guerreschi P, Pasquesoone L. [Deep alkali burns: Evaluation of a two-step surgical strategy]. Annales de chirurgie plastique et esthetique. 2018 Jun:63(3):191-196. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2018.03.008. Epub 2018 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 29653673]

Regan A, Hotwagner DT. Burn Fluid Management. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30480960]

Burn and Trauma Branch of Chinese Geriatrics Society, Ming J, Lei P, Duan JL, Tan JH, Lou HP, Di DY, Wang DY. [National experts consensus on tracheotomy and intubation for burn patients (2018 version)]. Zhonghua shao shang za zhi = Zhonghua shaoshang zazhi = Chinese journal of burns. 2018 Nov 9:34(11):E006. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-2587.2018.11.E006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30440148]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMason SA, Nathens AB, Byrne JP, Ellis J, Fowler RA, Gonzalez A, Karanicolas PJ, Moineddin R, Jeschke MG. Association Between Burn Injury and Mental Illness among Burn Survivors: A Population-Based, Self-Matched, Longitudinal Cohort Study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2017 Oct:225(4):516-524. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.06.004. Epub 2017 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 28774550]

Passaretti D, Billmire DA. Management of pediatric burns. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2003 Sep:14(5):713-8 [PubMed PMID: 14501335]