Continuing Education Activity

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a rare monoclonal lymphoid neoplasm characterized by the following four features: HL usually presents in young adults, commonly arises in cervical lymph nodes, involves scattered large mononuclear Hodgkin and multinucleated Reed-Sternberg cells on a background of non-neoplastic inflammatory cells, and characteristic neoplastic cells are often surrounded by T lymphocytes. Hodgkin lymphoma generally has an excellent prognosis, though this depends on several factors. HL is divided into two distinct categories that demonstrate different pathologic and clinical features: classical Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLP-HL). Classical Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for approximately 95 percent of HL and is further subdivided into four subgroups: nodular sclerosis (NSHL), lymphocyte-rich (LRHL), mixed cellularity (MCHL), and lymphocyte-depleted (LDHL). This activity illustrates the evaluation, treatment, and complications of Hodgkin lymphoma and the importance of an interprofessional team approach to its management.

Objectives:

Outline the distinguishing features of each classical type of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Review the presentation of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Explain how appropriate treatment of a case of Hodgkin lymphoma is determined.

Review the role of interprofessional team members in optimizing collaboration and communication to ensure patients with Hodgkin lymphoma receive high-quality care, which will lead to enhanced outcomes.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), formerly called Hodgkin disease, is a rare monoclonal lymphoid neoplasm with high cure rates. Biological and clinical studies have divided this disease entity into two distinct categories: classical Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLP-HL). These two disease entities show differences in the clinical picture and pathology. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for approximately 95% of all HL, and it is further subdivided into four subgroups: nodular sclerosis (NSHL), lymphocyte-rich (LRHL), mixed cellularity (MCHL), and lymphocyte-depleted (LDHL). Four features characterize Hodgkin lymphomas. They commonly arise in the cervical lymph nodes; the disease is more common in young adults; there are scattered large mononuclear Hodgkin and multinucleated cells (Reed-Sternberg) intermixed in a background of a mixture of non-neoplastic inflammatory cells; finally, T lymphocytes are often observed surrounding the characteristic neoplastic cells. Hodgkin lymphoma has an excellent overall prognosis with approximately an 80% cure rate.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The exact etiology of Hodgkin lymphoma is unknown. However, there is an increased risk of Hodgkin lymphoma in Epstein-Barr (EBV) and Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, autoimmune diseases, and immunosuppression. There is also evidence of familial predisposition in Hodgkin lymphoma. EBV has been found to be more common in the mixed cellularity and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma. Loss of immune surveillance has been proposed as the possible disease etiology in EBV-positive disease. No other viruses have been found to play a major contributing role in disease pathogenesis. Immunosuppression secondary to a solid organ or hematopoietic cell transplantation, therapy with immunosuppressive drugs, and human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection have all a higher risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma. HIV patients commonly present with a more advanced stage, unusual lymph node sites, and a poor prognosis. Studies found that there is a ten-fold increase in developing HL in same-sex siblings of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, suggesting a gene-environment interaction role in Hodgkin lymphoma predisposition.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Hodgkin lymphoma is a rare malignancy with an estimated incidence rate of 2.6 cases per 100,000 people in the United States. The disease represents 11% of all lymphomas seen in the United States. It has a bimodal distribution where most of the affected patients are between ages 20 to 40 years, and there is another peak from age 55 years and older. It affects males more than females, especially in the pediatric population, where 85% of cases occur in boys. Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in young adults, whereas mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma tends to affect older adults. The incidence of classical Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes is as follows: nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma (70%), mixed cellularity classical HL (25%), lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma (5%), and lymphocyte-depleted classical HL (less than 1%). Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) represents approximately 5% of Hodgkin lymphoma in general.

Pathophysiology

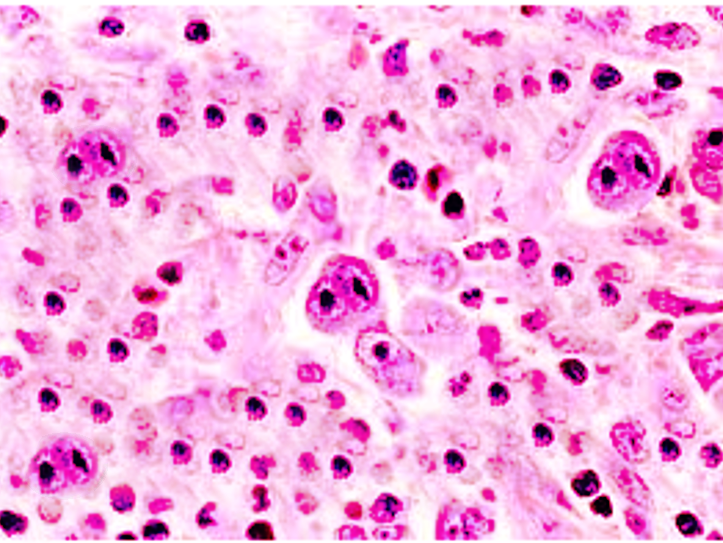

Hodgkin lymphoma has unique neoplastic cells in both the classical and NLP-HL types. Reed-Sternberg (RS) cell is a neoplastic, large multinucleated cell with two mirror-image nuclei (owl eyes) within a reactive cellular background. The RS cell is pathognomonic for classical HL. RS cells are derived from germinal center B cells with mutations of the IgH-variable region segment. The RS secrete cytokines to recruit reactive cells that include IL-5 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta). The RS cell is usually aneuploid with no consistent cytogenetic abnormality. Clonal Ig gene rearrangements have been found in the majority of isolated RS cells. Immunohistochemistry stains for RS cells are positive for CD30 and CD15 but typically negative for CD20 and CD45, which are positive only in neoplastic NLP-HL cells. In addition to CD15 and CD30, RS cells are usually positive for PAX5, CD25, HLA-DR, ICAM-1, Fascin, CD95 (apo-1/fas), TRAF1, CD40, and CD86. There are RS cell variants that include the Hodgkin cell, mummified cells, and lacunar cells. Hodgkin cells are mononuclear RS-cell variants.

Mummified cells show condensed cytoplasm and pyknotic reddish nuclei with smudgy chromatin. Lacunar cells have multilobulated nuclei, small nucleoli, and abundant, pale cytoplasm that often retracts during tissue fixation and sectioning, leaving the nucleus in what appears to be empty space (lacune-like space).

On the other hand, NLP-HL lacks the typical RS cells but has lymphocytic and histiocytic cells, which are characterized by larger cells with folded multilobulated nuclei (also known as “popcorn cells” or LP cells). The LP cells show a nucleus with multiple nucleoli that are basophilic and smaller than those seen in RS cells. LP cells show clonally rearranged immunoglobulin genes that are only detected in isolated single LP cells. The LP cells are usually positive for C020, CD45, EMA, CD79a, CD75, BCL6, BOB.1, OCT2, and J chain.

Histopathology

Morphology is used to determine Hodgkin lymphoma variants and NLP-HL. Nodular sclerosis HL shows a partially nodular growth pattern with fibrous bands and an inflammatory background. RS cells are rare. However, lacunar cells are more common. Mixed cellularity HL shows a diffuse or vaguely nodular growth pattern without sclerosis bands in an inflammatory background. Fine interstitial fibrosis may be present, and classical diagnostic Reed Sternberg cells are common.

Lymphocyte-rich HL commonly shows a nodular growth pattern in an inflammatory background that consists predominantly of lymphocytes, with rare or no eosinophils or neutrophils. RS cells and mononuclear Hodgkin cells are usually present. Lymphocyte depleted HL has a diffuse hypocellular growth pattern with increased areas of fibrosis, necrosis, and uncommon inflammatory cells. RS cells are usually present. NLPHL is characterized by overall nodular architecture with LP cells in a background of small B lymphocytes, follicular dendritic cells, and follicular T lymphocytes. In conclusion, morphology and immunophenotype of both the neoplastic cells and the background infiltrate are crucial in diagnosing HL and its different subtypes. In summary, correct morphological and immunophenotypic assessment in HL is important for the correct diagnosis of the disease entity.

History and Physical

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma frequently present with painless supra-diaphragmatic lymphadenopathy (one to two lymph node areas), B symptoms including unexplained profound weight loss, high fevers, and drenching night sweats. B symptoms are evident in up to 30% of patients and are generally more common in stages 3 to 4 of the disease, mixed cellularity, and lymphocyte depleted HL subtypes. Pain in lymph nodes may occur with alcohol consumption (paraneoplastic symptom). Chronic pruritus is another disease symptom that may be encountered. If mediastinal node enlargement is significant, the mass effect can produce chest pain and shortness of breath. If the patient has an extranodal disease, which is less common, related clinical manifestations may occur.

Each subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma has distinct clinical features. Nodular sclerosis subtype affects young adults and presents with early disease stage, while mixed cellularity HL is prevalent in both children and elderly patients and commonly presents with advanced disease stage. Lymphocyte depletion HL presents with extensive extranodal disease, affects elderly patients, and is associated with AIDS infection. Lymphocyte-rich classical HL presents with localized painless peripheral lymphadenopathy similar to NLP-HL. NLP-HL is a distinct, unique clinicopathological entity that is distinct from classical HL. It presents in males with localized painless peripheral lymphadenopathy in the neck that often spares the mediastinum. NLP-HL shows a more indolent course with a tendency for late relapses.[7][8][9]

Evaluation

Definitive diagnosis for Hodgkin lymphoma is through biopsy from a lymph node or suspected organ. It is important to note that fine-needle aspiration or core-needle biopsy frequently shows non-specific findings because of the low ratio of malignant cells and loss of architectural information. Excisional biopsy should be pursued if suspicion of Hodgkin lymphoma is high. An RS cell or LP cell needs to be identified within the biopsy specimen to establish a definitive diagnosis. Further workup is essential to determine the stage, which guides treatment and provides prognostic information.

Laboratory tests include complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel (CMP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV.

LDH levels correlate with the bulk of disease. Elevated levels of alkaline phosphatase may suggest liver or bone involvement. Testing for HIV is recommended as the treatment of the infection can improve outcomes in HIV-positive individuals.

Serum cytokines IL 6, IL 10, and soluble CD 25 correlate with systemic symptoms and prognosis.

Chest x-ray, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis, and PET/CT scans can help with staging. PET-CT scanning has now become a standard test for assessment of treatment response in HL and most lymphomas. Overall, a comprehensive workup is essential for both diagnosis and staging of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma largely depends on the histologic characteristics, the stage of the disease, and the presence or absence of prognostic factors. The goal of treatment for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma is to cure the disease with control of short and long-term complications. There are several different staging systems for Hodgkin lymphoma, and the Cotswolds modified Ann Arbor classification is commonly used. The International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin's lymphoma identified 7 variables for patients with advanced disease:

- Age older than 45 years

- Stage-IV disease

- Male gender

- WBC greater than 15,000/mL

- Lymphocyte less than 600/mL

- Albumin less than 4.0 g/dL

- Hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL

Risk stratification categorizes patients as low risk or high risk for recurrence. The response to therapy is determined by a PET scan and is used to optimize therapy. The initial treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma depends on subgroup treatment. There are three treatment subgroups: patients with early-stage disease with favorable prognostic factors, patients with limited-stage disease who have unfavorable prognostic factors, and those with advanced-stage disease. Patients who are in early-stage (stage I to IIA) with favorable prognostic features are treated with short duration of chemotherapy, typically two cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) followed by restricted involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT).

Patients who are in limited-stage disease but with unfavorable features such as bulky mediastinal disease, elevated ESR, and extra-nodal extension are treated with a longer course of chemotherapy (4 to 6 cycles) followed by a higher dose of IFRT. Patients with advanced-stage (stage IIB to IV) are risk-stratified by a different scoring system, the International Prognostic Score (IPS). Depending on IPS, different chemotherapy regimens (for example, escalated BEACOPP and Stanford V) can be used, but the standard of care is ABVD for most patients.

Radiation, in general, is not beneficial in these patients. Despite the high cure rate with initial therapy, approximately 10% of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma are refractory to initial treatment, and up to 30% of patients will relapse after achieving an initial complete remission. High-dose chemotherapy, followed by an autologous stem cell transplant, is the standard of care for the majority of patients who are refractory or relapse post-initial therapy. For patients who fail autologous transplantation, treatment options include brentuximab vedotin, PD-1 blockade, non-myeloablative allogeneic transplantation, or clinical trials. Future directions in the management of Hodgkin lymphoma will include the incorporation of frontline therapeutics that have shown efficacy in refractory/relapse disease settings, as well as other possible novel therapeutics.[10][11][12][13]

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is done in refractory or relapsed patients.

Differential Diagnosis

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Peripheral T cell lymphoma

- ALK1+ anaplastic (Ki-1) large cell lymphoma

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Staging

Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma is based on clinical staging of the disease. The modified Ann Arbor staging system is the most common. The staging system for Hodgkin lymphoma is based on the location of lymphadenopathy, the number and size of the lymph node, and whether the extranodal lymph node involvement is shown systemic. The commonly used staging system divides the disease into four stages:

- Stage I: Involvement of single lymph node regions or lymphoid structure

- Stage II: Involvement of 2 or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm; the number of anatomic sites should be indicated in a suffix (e.g., II2)

- Stage III: Involvement of lymph nodes or structures on both sides of the diaphragm

- III1: With or without splenic, hilar, celiac, or portal nodes

- III2: With paraaortic, iliac or mesenteric nodes

- Stage IV: Involvement of extranodal sites beyond those designated as E (E: single extranodal site, or contiguous or proximal to the known nodal site of disease)

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on several prognostic factors, including disease stage. Disease stage is currently only one factor in the prognostic indices used for pretreatment risk stratification and assessment. The 5-year overall survival (OS) in stage 1 or 2a is approximately 90%; on the other hand, stage 4 disease has a 5-year OS of approximately 60%.

Complications

Cardiac disease from mantle radiotherapy. This can lead to pericarditis, valvular heart disease, and coronary artery disease.

In addition, drugs like anthracyclines can cause cardiomyopathy.

Pulmonary disease can result from drugs like bleomycin and radiation therapy.

Secondary cancers are a common cause of morbidity and mortality. The most common secondary malignancy following treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma is lung cancer.

Myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia is also of major concern following alkylation therapy.

Other cancers that may develop include breast, soft tissue sarcoma, pancreatic, and thyroid.

Infertility varies but occurs in over 50% of patients.

Infectious complications do occur but can be managed with empirical antibiotic treatment.

Finally, patients may develop depression, peripheral neuropathy, family issues, and disturbed sexual functioning.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

All patients with Hodgkin lymphoma require long-term monitoring that includes:

- Annual history and physical exam

- Management of cardiac risk factors

- Vaccination in patients with splenectomy

- Stress test or echocardiogram

- Carotid ultrasound

- TSH, chemistry panel, and CBC

- Measurement of lipid levels and glucose

- Mammography in females

- Low-dose CT scan of the chest to detect lung lesions

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hodgkin lymphoma is a systemic disorder best managed by an interprofessional team for best outcomes.

The management of Hodgkin lymphoma is primarily by the oncologists. However, the patient may first present to the primary care provider or nurse practitioner with symptoms suggestive of the lymphoma. The key is prompt referral so that therapy can be initiated.

Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma largely depends on the histologic characteristics, the stage of the disease, and the presence or absence of prognostic factors. The goal of treatment for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma is to cure the disease with control of short and long-term complications.

The pharmacist has to educate the patient on the drugs, their benefits, and side effect profile. In addition, the pharmacist has to ensure that the patient has had the recommended preoperative workup before dispensing the drugs. The oncology nurse should monitor the patient for acute side effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs and educate the patient on minimizing complications.

Because many patients develop anxiety and depression, a mental health provider should provide appropriate counseling.

The dietitian should be involved in educating the patient on foods to eat and what to avoid.

The interprofessional team has to meet on a weekly basis to discuss patient care and future therapy. The communication between the members should be clear and open to ensure that the patient's treatment has not been jeopardized. Finally, if the patient is terminal, a hospice care team should be involved.

Outcomes

Prognosis depends on several prognostic factors, including disease stage. Disease stage is currently only one factor in the prognostic indices used for pretreatment risk stratification and assessment. The 5-year overall survival (OS) in stage 1 or 2a is approximately 90%; on the other hand, stage 4 disease has a 5-year OS of approximately 60%.[14][15] [Level 5]