Introduction

Rubeola, also known as measles, is a type of infectious disease. It is caused by a virus that is transmitted via person-to-person contact as well as airborne spread. Due to its mode of transmission and its ability to remain airborne for a prolonged period, individuals become easily infected.[1] Its high contagiousness and its inherent infective efficiency result in continued yearly multiple outbreaks worldwide, especially in the unvaccinated.[1] When exposed to measles, the individual not only develops clinical manifestations but is at risk for various complications. It continues to be a leading cause of death in children younger than 5 worldwide, and survivors are at risk of neurologic, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal complications.[1][2]

There is no specific antiviral therapy in the treatment of this condition, only supportive care.[1] Thus, the clinician needs to understand their role in prevention. This includes appreciating the nature of this disease, recognizing its presence, understanding its pathophysiology, providing immunizations to vaccine-eligible individuals, and being able to initiate early evaluation and treatment to not only treat the patient they are faced with but reduce the risk of spreading this disease. The following activity will provide an overview of the etiology, clinical features, evaluation, preventative strategies, and approach to the management of a patient with measles.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Measles is a helical symmetry virus with non-segmented negative polarity ribonucleic acid (RNA), a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and the morbillivirus genus. It contains approximately 15,894 nucleotides, encoding e8 viral proteins within 6 genes (nucleoprotein [H], phosphoprotein [P], matrix [M], the fusion protein [F], hemagglutinin [H], and the polymerase [L]) as well as having an RNA-bound RNA polymerase. The HN glycoprotein has neuraminidase and hemagglutinating activities in different places of the same molecule, which explains the absorption and lysis of the host receptors. The fusion glycoprotein is responsible for viral penetration into the host cell, as it stimulates the fusion of viral and cellular membranes. The matrix forms the basis of the lipid coat. The gene P encodes the messenger RNAs for the C and V proteins, and these proteins have involvement in the regulation of host cell immune response.[3][4]

Epidemiology

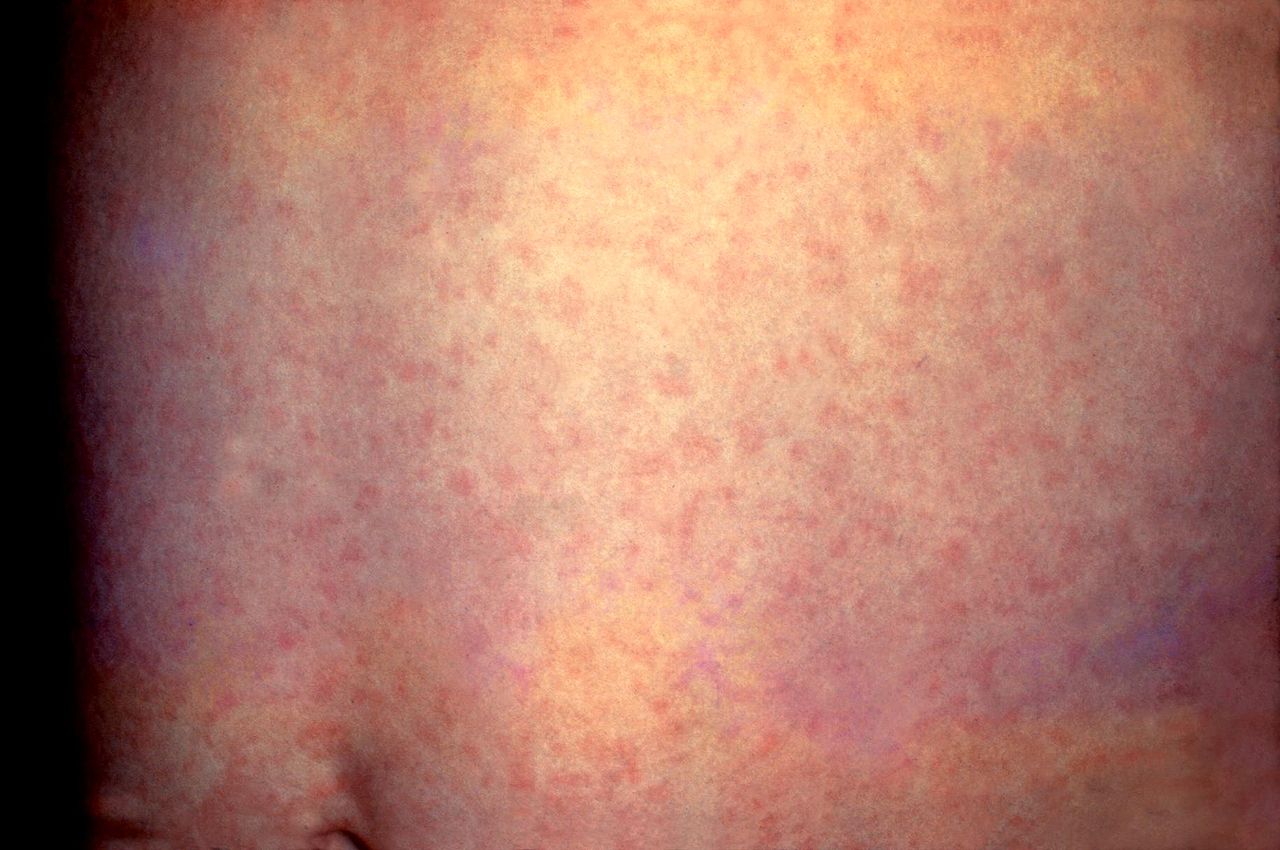

Measles is an acute and extremely contagious viral disease that has caused approximately 2.6 million deaths before the introduction of the vaccine. The intensification of vaccination activities has had a decisive influence on the 75% reduction in measles deaths. In countries where measles has been virtually eliminated, cases imported from other countries remain an important source of infection. The vast majority of cases around the world occur in countries with poor health systems. In 2012, a Global Strategic Plan against Rubeola (measles) and Rubella was presented for the period 2012 to 2020, which sets out the following objectives: (1) reduce global measles mortality by at least 95% by the end of 2015 and (2) achieve the elimination of measles and rubella in at least 5 World Health Organization regions by 2020. See Image. German Measles, Rubella.

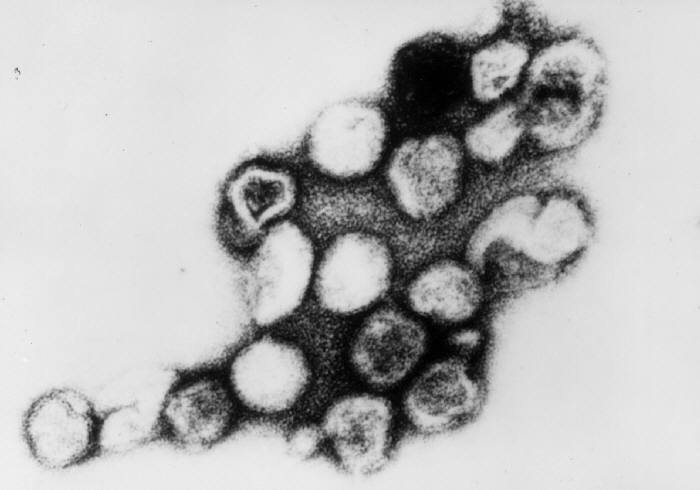

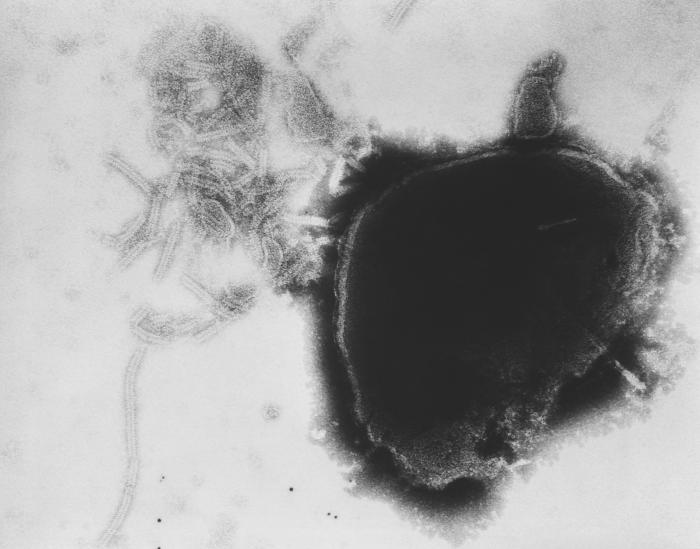

Measles is an exclusively human disease caused by a virus that belongs to the Paramyxovirus family, genus Morbillivirus, which infiltrates and grows within the epithelial cells of the pharynx and lungs. Its mode of transmission is mainly from person to person, by dissemination of droplets of flügge through the air (see Image. Paramyxovirus Virion Under Transmission, Electron Microscope). When the virus is in the air or on an infected surface, it remains active and contagious for periods of up to 2 hours. The virus can then be transmitted by an individual infected from 4 days before to 4 days after the appearance of the rash (see Image. Rubella Virus, Transmission Electron Micrograph). The measles virus incubation period varies from 7 to 18 days from exposure to the onset of fever and about 14 days until the rash appears (see Image. Measles, Day 4 Rash). The measles virus seems to be antigenically stable, and there is no evidence that viral antigens have changed much over time.

In temperate climates, outbreaks usually occur in late winter and early spring; however, in tropical climates, the transmission occurs after the rainy season. Measles most often affects preschoolers between 4 and 5 of age. It can take a more devastating course in certain special populations. For example, children living in developing countries are at risk for malnutrition and weaker healthcare systems; pregnant women (which increases the risk of complications including abortion, preterm labor, and low birth weight); and immunosuppressed patients with alterations of either cellular or humoral immunity.[1][5][4][6]

Pathophysiology

Once the virus penetrates the organism through the nasopharyngeal or conjunctival mucosa, it utilizes the H glycoprotein to bind and attach to host cells. The first area it reaches is the regional lymph nodes, where it infects lymphocytes, multiplies, and starts to spread systematically. The virus then reaches the lymphoreticular cells of the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and other organs. In these sites, it continues to multiply and spreads through the bloodstream, generating secondary viremia. This secondary viremia initiates the prodromal period of the disease, 6 to 7 days before the appearance of the rash. When the virus reaches the cells of any tissue, it produces a mononuclear reaction, with inflammatory foci distributed throughout the body. Within these foci, multicellular giant cells are formed that include intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies.

The infection begins after the binding of hemagglutinin to its cellular receptor. The virus spreads from cell to cell utilizing the fusion glycoprotein protein, which induces viral fusion with the cell membrane, releasing its ribonucleoprotein complex to the cytoplasm so that, after transcription and replication, new viral particles are generated that germinate outside the cell. The immune response is suppressed by the measles virus utilization of viral proteins V and C that suppress host interferon production and facilitate its replication.[3][4][5][7]

History and Physical

The clinical picture of measles can be divided into 3 stages: prodromal, eruptive, and convalescent, and should be suspected in patients with the classic triad of the three “Cs”: cough, conjunctivitis, and coryza.

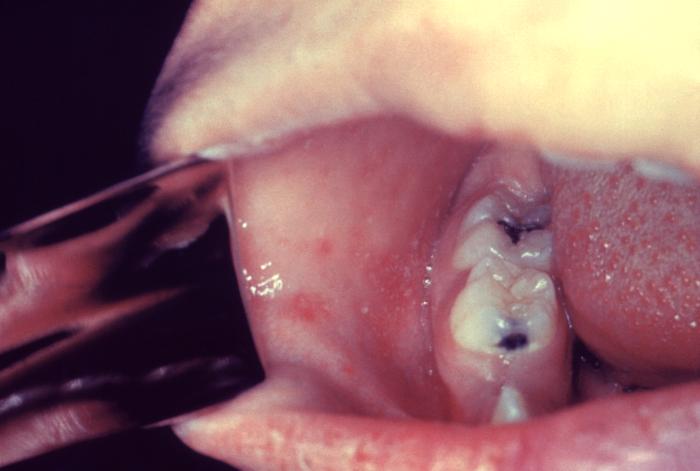

- The primary or prodromal phase lasts 4 to 6 days and is characterized by the presence of high fever, malaise, coryza, conjunctivitis, palpebral edema, and dry cough. Most cases show the characteristic Koplik spots of the disease, located in the buccal mucosa at the height of the second molar, and appear 2 to 3 days before the rash and disappear on the third day (see Image. Koplik Spots, Measles).

- The second phase, the eruptive, is characterized by the appearance of a maculopapular rash, initially fine, then subsequently becomes confluent. The rash begins behind the auricle and along the hair implantation line and extends downward to the face, trunk, and extremities.

- The third phase, or convalescence, occurs after 3 to 4 days when the rash begins to disappear in the same order in which it appeared, leaving brown spots and producing a thin peeling of the skin. The fever disappears 2 to 3 days after the rash begins, as does the general malaise. In atypical measles, the onset is acute, with high fever, headache, abdominal pain, and myalgia. The rash may be minimal in children with measles modified by the vaccine. In addition, they may not have 1 or more of the classic triad—cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. Unusual manifestations of measles include pneumonia, otitis media, myocarditis, pericarditis, and encephalitis.[1][3][5]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of measles is based on three elements: clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and laboratory testing. Serological tests with specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) measurements, molecular biologic techniques with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction application, and viral isolation are available for diagnostic confirmation. The measles-specific IgM antibody in primary infection, which is confirmatory of disease, is detected from the third day of the rash and remains positive for 30 to 60 days. For the evaluation of IgG, there is more than a four-fold increase in antibodies between the acute and convalescence phases of the disease. Measles RNA can be detected by a polymerase chain reaction from pharyngeal or nasopharyngeal swabs or urine samples. This test confirms the disease and allows the genotyping of the agent.[3][7]

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of measles treatment is prevention via routine immunization, which is highly effective in the prevention of measles.[8] For children, vaccination begins with the first dose between the ages of 12 to 15 months, followed by a second dose at 4 to 6 years, though it can be administered as early as 28 days after the first dose if the patient is above 12 months of age.[1] For children residing in or traveling to areas with a measles outbreak or the potential for a measles outbreak when traveling outside of the United States, early measles vaccination (one dose) is recommended for children greater than 6 months but less than 12 months of age (with the continued routine administration of the two-dose regimen after 12 months).[1]

In patients without evidence of immunity and who are exposed to measles, the following is recommended based on the patient’s clinical circumstances:

- Pediatric:

- For infants 0 to 5 months of age, it is recommended that they receive immune globulin within 6 days of exposure.

- For infants 6 to 11 months of age, it is recommended that they receive either a measles vaccination within 72 hours of exposure or immune globulin within 6 days of exposure.

- For children greater than 12 months of age who are unvaccinated, it is recommended that they receive measles vaccination within 72 hours of exposure (preferred over immune globulin). If the exposure occurred more than 72 hours but within 6 days, the patient should receive immune globulin if they have not received at least 1 dose of the measles vaccine (unless the child is severely immunocompromised; see below).

- Pregnant women without evidence of immunity:

- It is recommended that they receive immune globulin.

- Measles vaccination, in conjunction with mumps and rubella, is contraindicated.

- For immunocompromised:

- Immune globulin should be administered regardless of immunologic or vaccination status.

- Healthcare workers:

- Two doses of measles vaccine at routine intervals should be administered for unvaccinated healthcare personnel regardless of the birth year who lack laboratory evidence of measles immunity or laboratory confirmation of disease.

- Healthcare workers who lack evidence of immunity and who were exposed to a patient with measles should be excluded from the workplace from day 5 through day 21 after exposure.[8][9]

(A1)

Note: Individuals without evidence of immunity with measles exposure who received immune globulin should subsequently receive a measles vaccine no earlier than 6 months after immune globulin administration unless measles vaccination is contraindicated.[8] When presented with a potential case of measles, airborne transmission precautions should be initiated and maintained for four days after the rash presentation in otherwise healthy individuals and the duration of illness for immunocompromised patients.[1][10]

There is no specific treatment for measles except supportive care to relieve common symptoms associated with this condition. Supportive measures include antipyretics for fevers, hydration, and adequate nutritional support, including the encouragement of breastfeeding.[1] The World Health Organization recommends the administration of vitamin A for all children with measles, but particularly for children who reside in areas where the case fatality rate is more than 1%, areas with known vitamin A deficiency, and in severe cases of complicated measles. In normal circumstances, vitamin A maintains epithelial tissue and is crucial for immunological function. During a measles infection, vitamin A stores are depleted, resulting in an inability to resist the current and secondary infections associated with measles.[11](A1)

If indicated, the first dose should be provided immediately upon diagnosis and a second dose the following day. For infants less than 6 months of age, the doses are 50,000 IU; for children between 6 and 12 months, 100,000 IU; and for children aged 12 months and older, 200,000 IU.[11] A Cochrane review article illustrated a reduced risk of overall mortality as well as pneumonia-specific mortality with the two consecutive day dosing of 200,000 IU. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vitamin A administration for all children with severe measles.[7][11] The measles virus is susceptible to the medication ribavirin in vitro, but due to a lack of clinical data, its routine use is not recommended.[12] It may be considered for use in certain high-risk groups.[13](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Measles should be distinguished from similar presenting exanthemic diseases of childhood, autoimmune processes, and adverse drug reactions. Rubella causes a rash similar to measles with head-caudal distribution, mild respiratory symptoms, and the absence of conjunctivitis. Still, it is accompanied by the presence of adenopathies—which is characteristic of this disease. Roseola is characterized by an illness beginning with a high fever, which subsides after a few days, accompanied by the appearance of a rash in the central part of the body, without the presence of Koplik points. Mononucleosis is a febrile viral disease, a characteristic course with few symptoms during childhood, contrary to what happens in more advanced ages. Mononucleosis manifests itself by pharyngeal compromise, polyadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, and the rash can have different forms of presentation. In Kawasaki disease, there is an ocular compromise with the presence of conjunctivitis without exudate, and the respiratory compromise is not part of this pathology. Group A Streptococcus (particularly scarlet fever) may present with a similar rash (a coarse, sandpaper-like, blanching, erythematous) to measles in association with pharyngitis.[5][14]

Prognosis

Most patients recover from this disease without significant morbidities. In developing countries, however, children who are malnourished, immunocompromised, and pregnant women have a case fatality rate reported as high as 12%. This is attributed to complications from measles, including respiratory failure and encephalitis.[15][16] Pregnant women who are infected are at risk of premature birth, spontaneous abortion, and intrauterine death.[16]

Complications

Pregnant women, young infants, and immunocompromised patients are at the greatest risk of complications. These complications include diarrhea, laryngotracheobronchitis, pneumonia, otitis media, encephalitis, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Pulmonary involvement with the measles virus is common and can be due to the measles virus itself or later in the course of illness because of bacterial superinfection (ie, pneumonia associated with common bacterial pathogens). Otitis media is often a bacterial otitis media that is a superinfection following the initial measles infection. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis occurs in measles as a result of persistent infection in the central nervous system that occurs several years after the initial infection. Demyelination of white matter is an early finding with an insidious onset that progresses to abnormal behaviors, myoclonic movements, seizures, dementia, coma, and death. Death from subacute sclerosing panencephalitis is inevitable within 1 to 3 years after diagnosis. Death from measles is often caused by viral pneumonia, secondary bacterial pneumonia, and postviral encephalitis.[5][7][17][18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and parents of vaccine-eligible children should be counseled on the high infectivity of measles and the benefits of vaccination.[1] Patients and parents should also be counseled that measles vaccination is associated with adverse events, including fever, rashes, and lymphadenopathy, but serious adverse events are rare (ie, anaphylaxis, febrile seizures, thrombocytopenic purpura, and measles inclusion-body encephalitis).[1] The possibility or risk of autism may be inquired when a measles vaccination is recommended, particularly by parents of vaccine-eligible children. In these cases, the parents should be advised that the initial studies that demonstrated an association between measles vaccination and autism were falsified, and subsequent studies have not supported such an association with this condition.[1]

Pearls and Other Issues

Preventive measures are based on the timely vaccination of the susceptible population and public health actions before the appearance of suspicious cases within the first 72 hours. While balancing the need for preventive immunization, the healthcare provider must maintain communication and achieve the trust of the population to achieve a high likelihood of vaccination acceptance. There are several measles vaccines made with live attenuated viruses—these can be in the form of single-antigen vaccines or combination with rubella or mumps and rubella vaccines. The measles vaccine is usually given by subcutaneous injection, but intramuscular administration is also effective. World Health Organization guidelines state that 2 doses of measles vaccination should be applied, with variations in the timing of the first dose depending on endemic situations and settings. The first dose of the vaccine is usually at nine months of age in endemic settings, but from 6 months of age in some circumstances, including during outbreaks, for displaced populations and refugees, for children infected and exposed to human immunodeficiency virus, and for children at high risk of contracting measles. There is also some flexibility, according to local epidemiology. Administering the first dose of the vaccine at 12 to 15 months results in a higher proportion of protected children but can only be done in settings where the risk is low. The second dose of the vaccine is given at four to five years of life.[1][7][19][6][20]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Measles has been and is currently responsible for a large number of deaths worldwide, mainly in children younger than 5 in countries that do not apply the measles vaccine. Therefore, the best way to prevent measles and ultimately achieve its worldwide eradication is through vaccination.[21] This is why it is important to keep the population informed about the safety and efficaciousness that vaccinations offer against this disease. Also, maintaining active epidemiological surveillance of all suspected measles cases of any age is a fundamental axis in the control of this disease. The diagnosis and management of measles require an interprofessional approach to avoid complications from the underrecognition of measles and avoid the person-to-person spread of this virus. This requires collaboration with bedside nursing, infection control, and infectious disease specialists to initiate and maintain airborne precautions.[1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Koplik Spots, Measles. This patient presented on the third pre-eruptive day with “Koplik spots” indicative of the beginning onset of measles. In the prodromal or beginning stages, one of the signs of the onset of measles is the eruption of “Koplik spots” on the mucosa of the cheeks and tongue. These spots appear as irregularly shaped, bright red spots, often with a bluish-white central dot.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

German Measles, Rubella. This patient presented with a generalized rash on the abdomen caused by German measles (rubella). The rash usually lasts about three days and may be accompanied by a low-grade fever. Rubella is caused by a different virus from the one that causes regular measles (rubeola). Immunity to rubella does not protect a person from measles or vice versa.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Rubella Virus, Transmission Electron Micrograph. The virus can be transmitted by an individual infected from 4 days before to 4 days after the appearance of the rash.

Erskine Palmer, MD, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Measles, Day 4 Rash. This child shows a classic day 4 rash with measles.

Barbara Rice, NP, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Paramyxovirus Virion Under Transmission, Electron Microscope. The image displays the viral nucleocapsid of a paramyxovirus virion as visualized under a transmission electron microscope.

Fred Murphy, MD, Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Strebel PM, Orenstein WA. Measles. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 Jul 25:381(4):349-357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1905181. Epub 2019 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 31184814]

Stein CE, Birmingham M, Kurian M, Duclos P, Strebel P. The global burden of measles in the year 2000--a model that uses country-specific indicators. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003 May 15:187 Suppl 1():S8-14 [PubMed PMID: 12721886]

Leung AK, Hon KL, Leong KF, Sergi CM. Measles: a disease often forgotten but not gone. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2018 Oct:24(5):512-520. doi: 10.12809/hkmj187470. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30245481]

Guseva S, Milles S, Blackledge M, Ruigrok RWH. The Nucleoprotein and Phosphoprotein of Measles Virus. Frontiers in microbiology. 2019:10():1832. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01832. Epub 2019 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 31496998]

Porter A, Goldfarb J. Measles: A dangerous vaccine-preventable disease returns. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2019 Jun:86(6):393-398. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.19065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31204978]

Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Dec 2:390(10111):2490-2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31463-0. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28673424]

Khan L. Measles in Children. Pediatric annals. 2018 Sep 1:47(9):e340-e344. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20180801-01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30208191]

McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2013 Jun 14:62(RR-04):1-34 [PubMed PMID: 23760231]

. Immunization of health-care workers: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 1997 Dec 26:46(RR-18):1-42 [PubMed PMID: 9427216]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFiebelkorn AP, Redd SB, Kuhar DT. Measles in Healthcare Facilities in the United States During the Postelimination Era, 2001-2014. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Aug 15:61(4):615-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ387. Epub 2015 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 25979309]

Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M. Vitamin A for treating measles in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2005 Oct 19:2005(4):CD001479 [PubMed PMID: 16235283]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePal G. Effects of ribavirin on measles. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 2011 Sep:109(9):666-7 [PubMed PMID: 22480102]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBichon A, Aubry C, Benarous L, Drouet H, Zandotti C, Parola P, Lagier JC. Case report: Ribavirin and vitamin A in a severe case of measles. Medicine. 2017 Dec:96(50):e9154. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29390321]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasetti S, Hodgson J, Rawson TM, Majeed A. Scarlet fever: a guide for general practitioners. London journal of primary care. 2017 Sep:9(5):77-79. doi: 10.1080/17571472.2017.1365677. Epub 2017 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 29081840]

Nandy R, Handzel T, Zaneidou M, Biey J, Coddy RZ, Perry R, Strebel P, Cairns L. Case-fatality rate during a measles outbreak in eastern Niger in 2003. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Feb 1:42(3):322-8 [PubMed PMID: 16392075]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOgbuanu IU, Zeko S, Chu SY, Muroua C, Gerber S, De Wee R, Kretsinger K, Wannemuehler K, Gerndt K, Allies M, Sandhu HS, Goodson JL. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes associated with measles during pregnancy: Namibia, 2009-2010. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014 Apr:58(8):1086-92. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu037. Epub 2014 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 24457343]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGarg RK, Mahadevan A, Malhotra HS, Rizvi I, Kumar N, Uniyal R. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Reviews in medical virology. 2019 Sep:29(5):e2058. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2058. Epub 2019 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 31237061]

Caseris M, Burdet C, Lepeule R, Houhou N, Yeni P, Yazdanpanah Y, Joly V. [An update on measles]. La Revue de medecine interne. 2015 May:36(5):339-45. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2014.10.362. Epub 2015 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 25579464]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRussell CJ, Simões EAF, Hurwitz JL. Vaccines for the Paramyxoviruses and Pneumoviruses: Successes, Candidates, and Hurdles. Viral immunology. 2018 Mar:31(2):133-141. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0137. Epub 2018 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 29323621]

Chen HL, Tang RB. Measles re-emerges and recommendation of vaccination. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association : JCMA. 2020 Jan:83(1):5-7. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000210. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31569091]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Global measles mortality, 2000-2008. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2009 Dec 4:58(47):1321-6 [PubMed PMID: 19959985]