Introduction

Dysuria is the sensation of pain and/or burning, stinging, or itching of the urethra or urethral meatus associated with urination. It is a prevalent urinary symptom experienced by most people at least once in their lifetime. Dysuria typically occurs when urine comes in contact with the inflamed or irritated urethral mucosal lining. This is exacerbated by and associated with detrusor muscle contraction and urethral peristalsis, which stimulates the submucosal pain receptors, resulting in pain or a burning sensation during urination.[1]

True dysuria requires differentiation from other symptoms, which can also occur due to pelvic discomfort from various bladder conditions such as interstitial cystitis, prostatitis, and suprapubic or retropubic pain.[1] This distressing condition can be caused by multiple underlying factors, including urinary tract infections (UTIs), bladder inflammation, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), or even more serious conditions like kidney stones. Understanding dysuria's broad differential is critical in further management. Clinicians should recognize that further evaluation is warranted when dysuria is present. This will lead to improved recognition of potential abnormalities, which, in turn, will dictate treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of dysuria can be divided broadly into 2 categories: infectious and noninfectious. Infectious causes include UTIs, urethritis, pyelonephritis, prostatitis, vaginitis, and STIs. Noninfectious causes include skin conditions, foreign bodies or stones in the urinary tract, trauma, benign prostatic hypertrophy, and tumors. Additionally, interstitial cystitis, certain medications, specific anatomic abnormalities, menopause, reactive arthritis (Reiter syndrome), and atrophic vaginitis can all cause dysuria.[2]

One of the most common causes of dysuria is a UTI, which occurs in both males and females. Due to anatomical considerations, UTIs are much more common in females than males. In females, bacteria can reach the bladder more easily due to a shorter and straighter urethra than in males, as the bacteria have far less distance to travel to reach the bladder from the urethral meatus. Females who use the wrong wiping technique, from back to front instead of the preferred front to back, take baths instead of showers, or do not use washcloths to clean their vaginal area first when bathing, can predispose themselves to more frequent UTIs due to repeated contamination of the urethral meatus with perirectal and other bacteria.

Females also tend to experience dysuria more frequently than males due to their higher likelihood of recurrent UTIs. Most UTIs are uncomplicated and relatively simple to treat. However, persistent dysuria may be associated with complicated UTIs, which are found in men with UTIs, incompletely treated simple UTIs, prostatitis, pregnancy, immunocompromised status, catheters, nephrolithiasis, renal failure, dialysis, neurogenic bladder, anatomical or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract, pelvic floor dysfunction, and overactive bladder.[3]

The most common cause of male urethritis is infectious from sexually transmitted organisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Mycoplasma genitalium. Chlamydia is the most commonly identified cause of nongonococcal urethritis (found in about 50% of cases), followed by Mycoplasma genitalium.[4][5] Other organisms, such as Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum, are less commonly found.[5][6] Refractory cases should have testing for Trichomonas vaginalis. When testing patients suspected or at risk for STIs, consider screening for HIV and syphilis.

Gonorrhea is found in about 22% of symptomatic men, with an overall incidence of 213 cases per 100,000 males in 2018. And the incidence is increasing. Rates are significantly higher in non-Hispanic African Americans compared with the general population. Rates are also higher in the geographic South than in other US regions. Other parts of the world have even higher rates, such as a reported 62% incidence of gonorrhea in symptomatic men in South Africa.[7]

Urethritis associated with bacterial prostatitis is often caused by gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli (E coli). Chlamydia trachomatis most often causes dysuria and epididymitis in men younger than 35 years and by E coli, Pseudomonas, and other gram-negative coliforms in older men.

Dysuria associated with frequency and suprapubic pain without objective evidence of infection, inflammation, or any other identifiable cause is sometimes called urethral pain syndrome (formerly urethral syndrome). This is similar to mild interstitial cystitis, possibly just a different variation of the same disorder. Both lack positive urine findings of infection.

Urethral syndrome has more continuous but milder dysuria, usually described as a constant irritation. It is possibly related to urethral stenosis and/or hormonal imbalances, although the exact cause remains unknown. Painful spasms of the pelvic musculature are common. Suprapubic discomfort and urinary frequency may be present but are usually not the primary urinary symptoms and are generally less severe than interstitial cystitis. Urinary frequency is much more severe during the daytime, often requiring voiding every 30 to 60 minutes with little or no nocturia. Urethral syndrome patients are typically females ranging from 13 to 70 years of age.

Interstitial cystitis typically has more bladder discomfort, frequency, urgency, and pain when the bladder is full, somewhat relieved upon voiding.

Various foods can increase bladder and urethral irritation, of which caffeine is the most prevalent. High-potassium and hot, spicy foods also irritate the bladder and urethra. A complete, detailed list is available at: http://my.clevelandclinic.org/disorders.overactive_bladder/hic_bladder_irritating_foods.aspx.[2]

Uncommon causes of dysuria include endometriosis, atrophic vaginitis, urethral strictures, diverticula, inflammation or infection of the paraurethral/Skene's glands, syphilis, mycobacterium, herpes genitalis, and infected urachal cysts.[8] Other causes include a double-J urinary stent, recent urethral instrumentation or Foley catheterization, bladder calculi, prostatitis, traumatic sexual intercourse, pelvic floor dysfunction, herpes zoster, and lichen sclerosis.

Topically applied products, such as douches, bubble baths, and contraceptive gels, can also irritate the urethra. A clinical trial of avoiding all topical agents is reasonably warranted.

Overactive bladder will present with urgency and frequency as the primary symptoms. There may also be intermittent suprapubic pain or discomfort.

Epidemiology

Dysuria typically affects approximately 3% of all adults over 40 years of age at any given time, making it the most common urinary symptom.[2] Acute cystitis is the most common cause of dysuria. It accounts for about 7 million outpatient visits yearly in the United States, with one-fifth occurring in emergency departments.[2]

Pathophysiology

Dysuria typically occurs when urine comes in contact with the inflamed or irritated urethral mucosal lining. This is exacerbated by and associated with detrusor muscle contractions and urethral peristalsis, which stimulates the submucosal pain and sensory receptors, resulting in pain, itching, or a burning sensation during urination. Various inflammatory or neuropathic processes can increase the sensitivity of these receptors. Occasionally, inflammation from surrounding organs, such as the colon, can result in dysuria.

Noninfectious causes of dysuria, such as urinary calculi, tumors, trauma, strictures or foreign bodies, and atrophic vaginitis, can result from irritation of the urethral or bladder mucosa. Decreased capacity and elasticity of the detrusor muscle can cause urinary urgency or incontinence as well as dysuria.[9]

History and Physical

When someone presents with dysuria, it is essential to take a detailed history. The clinician must try to determine the timing, severity, duration, and persistence of the symptoms. For example, pain at the beginning of urination suggests a urethral problem such as urethritis. Pain at the end of urination may be from the bladder or prostate.

Initial history should include features of a possible local cause that may be causing dysuria, such as vaginal or urethral irritation. Any history regarding risk factors like pregnancy, the possibility of a kidney stone, trauma, tumor, recent urologic procedures, and possible urologic obstruction merits consideration. Patient history should include information regarding associated symptoms like fever, chills, flank pain, low back pain, nausea, vomiting, joint pains, hematuria, nocturia, urgency, frequency, and incontinence.

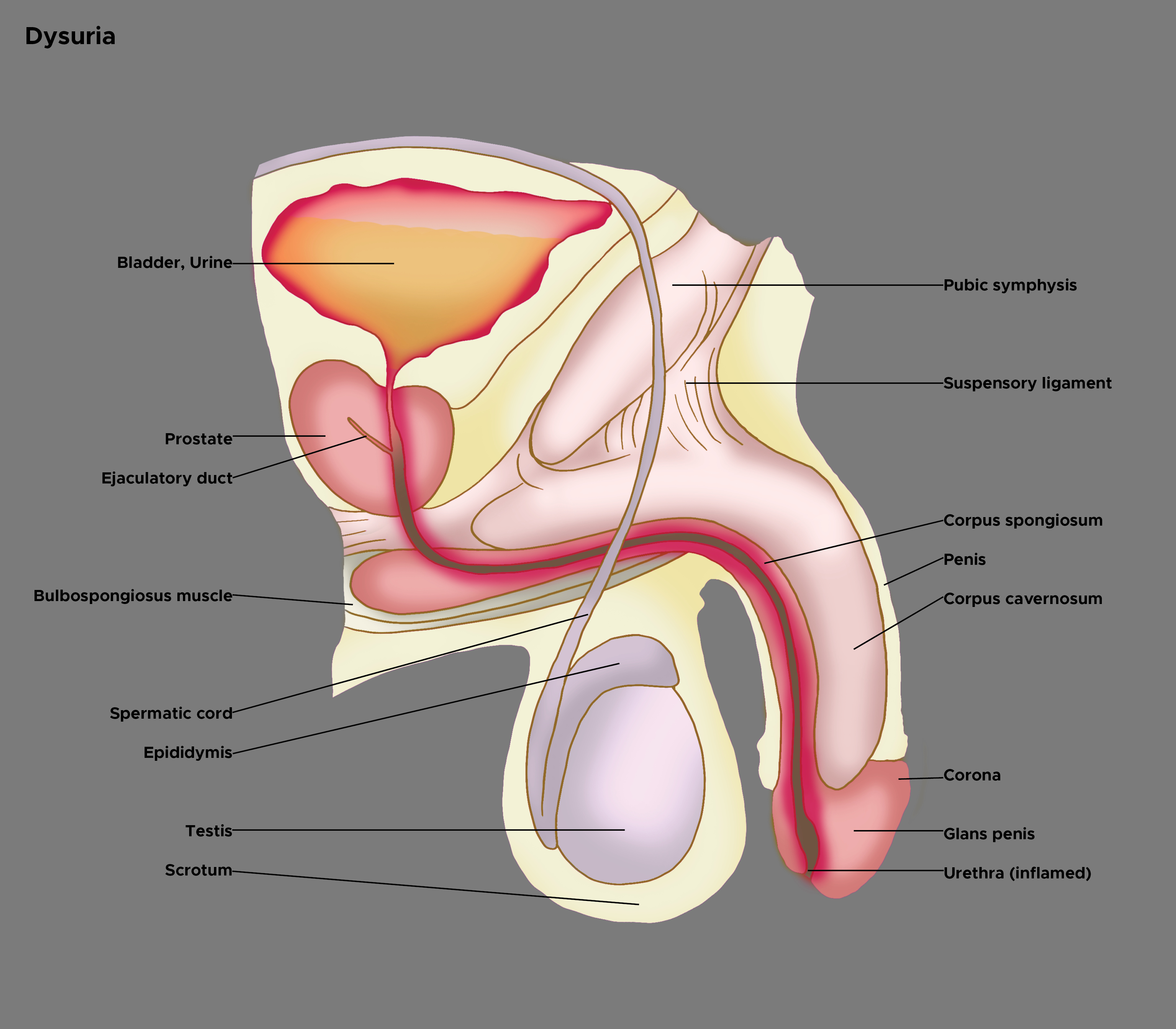

History regarding recent sexual activity is crucial. Attention must be given to gender-specific details. In women, it is essential to note menstrual history, complaints of vaginal discharge, and whether the patient is using contraception.[2][10] Males can present with different symptoms than females. Symptoms may highlight the anatomical site of pathology (see Image. Illustration of Dysuria). Males may experience perineal pain or obstructive urinary symptoms and dysuria, which could be caused by prostatitis.[11]

Male patients require inspection for a urethral discharge, and the urethral meatus should be checked for redness, crusting, and exudate. The inside lining of the underwear should also be checked for signs of discharge. If urethritis or a discharge is suspected, the urethra can be milked to elicit a specimen for testing. This is done by placing a gloved finger at the base of the penis on the ventral surface and pressing inwards. Then, slowly move the entire hand forward towards the glans. Any discharge produced should be collected for culture.

In older patients, a history regarding changes in mental status is necessary, as often, the most common symptom of a UTI in older adults is confusion. Obtaining a history regarding the recurrence of symptoms is also necessary.

A thorough physical examination should be performed. A purulent urethral discharge is suggestive of gonorrhea. Isolated dysuria without other symptoms is most likely from chlamydia. Dysuria with genital ulcers suggests possible herpes simplex virus, and balanoposthitis is sometimes associated with Mycobacterium genitalium.[12]

The clinician should also look for physical findings of fever, rash, direct tenderness over the bladder area, and joint pain. Physical findings of increased temperature, rapid pulse, or low blood pressure in the presence of dysuria can indicate systemic infection. Regional lymph nodes should be palpated. Urological obstruction due to a stone or tumor can result in findings of flank pain, hematuria, decreased urination, and bladder spasms. All these physical findings should be investigated carefully.

Evaluation

Evaluation of dysuria starts with taking a detailed history and performing a thorough physical examination. Associated signs and symptoms of hematuria, suprapubic tenderness, urinary frequency, urgency, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, low back pain, flank pain, joint pain, rash, etc, require close follow-up.

Urinalysis is the most useful test to start the workup in a patient with dysuria. Urinalyses positive for nitrites carry a high predictive value of a positive urine culture (75%-95%). Positive leukocytes (anything more than a trace positive) are also highly predictive but slightly less than nitrites (65%-85%). The presence of both positive nitrites and leukocytes on a dipstick is highly predictive.[13] Dysuria in a patient with only positive leukocyte esterase or pyuria in the urine suggests urethritis.[14]

Gram stain microscopy showing Gram-negative diplococci is diagnostic for gonorrhea. Typically, microscopic examination of urethral secretions demonstrating 5 white blood cells (WBCs) or more per oil immersion microscopic field is diagnostic for urethritis; however, some have suggested this cutoff be lowered to just 2 WBCs.[15][16] The most sensitive test for male gonorrhea or chlamydia is urinary nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). The sample should be obtained at least 20 minutes after the most recent void and optimally at least 1 hour afterward.[17]

Patients who do not respond to initial treatment and those with risk factors for a possible complicated UTI should have a full urine culture and sensitivity analysis performed. If a systemic infection is suspected, it is important to check a complete blood count and a metabolic panel, including serum creatinine, especially if the patient has nausea, vomiting, fever, or chills. Blood cultures must be performed if there is a suspicion of systemic spread of infection. In severe cases, hospitalization should be considered.[18]

If STIs are suspected, such as in younger, sexually active patients, a urethral or cervical/vaginal probe should be performed. Samples should be obtained to diagnose Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.[19] Women with vaginal symptoms should have a wet mount examination or a vaginal DNA probe. In male patients with suspected chronic prostatitis, gentle prostatic massage can help obtain a sample of the expressed prostatic secretions for a urine culture.[20]

If the patient has suspected hematuria and bladder cancer or has a significant (>10 pack-years) smoking history, then urine cytology can be helpful in addition to cystoscopy.[21] Imaging tests like ultrasonography or CT scan may be in order in cases of dysuria where patients show signs of having a complicated UTI, obstruction, unexplained fevers, flank pain, hydronephrosis, abscess, stones, or tumors.[22] However, imaging is not necessary in most cases of simple dysuria. In selected cases, cystoscopy can be performed to evaluate symptoms of chronic or intractable dysuria resistant to standard therapies, which can be associated with bladder cancer, vesicle stones, prostatitis, or hematuria.[23][24]

Urethral Pain Syndrome

Formerly urethral syndrome, this syndrome typically presents with dysuria as a key symptom. Other symptoms include urinary frequency and suprapubic discomfort.[25] The bladder pain is relieved somewhat by voiding. There may also be hesitancy, slowing of the urinary stream, and a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying. Urine cultures are typically negative, and the urinary symptoms are usually worse during the day than nighttime.

The original description of urethral syndrome was urinary frequency and dysuria without evidence of infection. It was thought to be primarily due to urethral stenosis treatable with serial urethral dilations. It is now believed that urethral dilations are only appropriate in a small minority of patients. Urethral pain syndrome is found predominantly in women aged 30 to 50 years. In this group of women, vaginal pathology (vaginal infections, atrophic vaginitis, and similar pathology) should be carefully excluded. It is thought that up to one-quarter of all patients, especially women, with lower urinary tract symptoms without a documented infection might have urethral pain syndrome.

The diagnosis is primarily one of exclusion. There is an overlap between urethral pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis, as there is a definite lack of consensus on specific criteria between these disorders, and they may not be mutually exclusive. The exact cause of urethral pain syndrome is unknown.

Reactive Arthritis

Formerly called Reiter syndrome, reactive arthritis was historically used to describe the combination of urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis. Arthritis is usually a postinfectious autoimmune response. Reiter syndrome reflects only a portion of all patients with reactive arthritis. It is defined as arthritis, which follows an infection that cannot be cultured from the affected joint.

When triggered by a sexually transmitted organism, the condition is called sexually acquired reactive arthritis. It usually presents in younger adults, with gastrointestinal and genitourinary infections being the most common triggering events. The most common causative genitourinary organism is Chlamydia trachomatis, followed by Chlamydia pneumoniae, E. coli, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Mycoplasma genitalium. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an immunotherapy for bladder cancer, has also been identified as a rare cause, affecting about 1% to 2% of treated patients.[26]

Recently, reactive arthritis cases have been reported following COVID-19 infections.[27][28][29] The arthritis produced is usually acute, nonsymmetrical, and typically affects the lower extremities (predominantly knees), although it may occur in almost any joint. This arthritis typically follows the original infection by 1 to 4 weeks.[30] Ocular effects are present in about 20% of all cases of reactive arthritis.[31] The diagnosis is made by clinical suspicion where there is a history of urethritis preceding arthritis and the lack of any evidence for other types of arthritis.

Urinary NAAT can help identify chlamydia and gonorrhea in suspected cases. Human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) testing will be positive in 30% to 50% of patients with reactive arthritis, but a negative test does not rule it out.

Appropriate antibiotic treatment is usually recommended for chlamydia-based reactive arthritis if an active infection is present.[32] Antibiotics for chronic infection-related arthritis are more controversial as most randomized trials of long-term antibiotic therapy show little or no improvement.[33][34] Treatment of arthritis includes NSAIDs, intra-articular and systemic glucocorticoids, and other disease-modifying agents such as sulfasalazine and methotrexate. The prognosis is usually good as reactive arthritis typically lasts only 3 to 5 months, and most patients enjoy a complete remission.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of dysuria depends on the underlying etiology whenever possible. The most common cause of dysuria is a UTI. Empiric antibiotic therapy based on a patient's history and symptoms is usually the most cost-effective treatment. No further evaluation is necessary in those cases where dysuria from uncomplicated UTI is suspected.[35] When the clinician suspects a complicated UTI, as in the presence of associated symptoms like nausea, vomiting, fever, or chills, then along with starting antibiotics, additional testing like blood cultures, a metabolic panel, or a complete blood count are all viable options. Imaging with ultrasonography or a CT scan can diagnose suspected pyelonephritis, stones, or urinary obstruction.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotic therapy for urethritis depends on the underlying organism, which is most likely sexually transmitted.[36]

Gonorrhea

- Treated with ceftriaxone, cefixime, ceftizoxime, cefoxitin, or azithromycin.[37]

- Quinolones are no longer recommended due to increasing resistance.

Nongonococcal urethritis

- Usually treated with single-dose azithromycin (1 gram) or doxycycline (100 mg BID for 7 days).[37]

- These regimens generally have about an 80% overall cure rate.[38] (A1)

Chlamydia

Mycoplasma

- A relatively common cause of persistent urethritis, mycoplasma demonstrates resistance to standard therapy with doxycycline, which now has a high failure rate.[40]

- Azithromycin appears more effective than doxycycline and is currently recommended for Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum.[37][41]

- An extended azithromycin regimen, which tends to avoid induced macrolide resistance, is also available (500 mg orally to start, then 250 mg daily for the next 4 days).[42] This is appropriate for those who fail initial doxycycline therapy.

- Ten days of moxifloxacin 400 mg daily is recommended if this azithromycin regimen fails.[43]

- Prolonged erythromycin therapy does not appear to be effective and is not recommended.

- Recurrent symptoms tend to be related to noncompliance, repeat exposure, chronic prostatitis, or infections with Trichomonas vaginalis or Mycoplasma genitalium. (A1)

Trichomonas

- Trichomonas is present in only about 2.5% of male urethritis cases.[44]

- When present, treatment is metronidazole 2 g for the patient and his or her partner. (B2)

Infrequent causes of urethritis include Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and Haemophilus influenza, which can be transmitted during oral sex.[45]

Physicians should be mindful of the possibility of antimicrobial resistance, and optimal antibiotics should be started based on likely pathogens, local resistance patterns, and costs (or insurance coverage) associated with the treatment.[46] When dysuria occurs due to chronic prostatitis in males, appropriate oral antibiotics are recommended after obtaining a urine culture.[47]

If the cause of dysuria is renal stones, various treatment options can be considered depending on the size and location of the calculi. Stones smaller than 5 mm typically pass on their own. Patients should be asked to hydrate themselves and strain the urine to document the evidence of a passed stone. Stones larger than 5 mm are treatable through various modalities, including extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and rarely open surgery.[48][49][50](B3)

When the patient presents with dysuria and a suspected perinephric abscess, an imaging study like ultrasonography or a CT scan should be performed. Once it is confirmed to be an abscess, the patient should be hospitalized and intravenous antibiotics should be initiated, followed by open surgical or percutaneous catheter drainage, or both.[51] (B3)

If the cause of dysuria is benign prostatic hypertrophy, medical treatment with alpha-blockers or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors should be considered. If the patient has no symptomatic improvement after trying the medical therapy, the surgical option of transurethral resection of the prostate should be considered, but this is typically reserved for other urinary symptoms rather than isolated dysuria.[52](B3)

Pudendal neuralgia and/or pelvic floor dysfunction may also cause dysuria in some patients and should be considered when standard dysuria treatments have failed.[53]

Historically, female urethral dilation has been used for many urological complaints in women, including dysuria, but this practice is rarely used today. Nevertheless, there may be the occasional female patient with urethral stenosis who would benefit from dilation.

There will inevitably be cases where no specific cause of dysuria can be found. In such cases, treatment tends to be symptomatic or holistic. Various generic dysuria treatments include the following:

Dietary Modification

- This approach can help many patients with isolated dysuria.

- Various foods and beverages have been reported to exacerbate dysuria symptoms, including:

- Alcoholic beverages

- Chilies

- Condiments

- Fruit juices, including cranberry juice

- High-potassium fruits like bananas, lemons, raisins, and tomatoes

- Highly acidic and spicy foods

- Hot sauces

- Ketchup

- Peppers

- Salad dressings

- Tomato sauces

- A more complete list is available on the Cleveland Clinic website.[2]

Phenazopyridine

- This medication can often temporarily relieve the irritation and stinging of dysuria and sometimes the urinary frequency accompanying it.

- For best results, it must be taken 3 times a day.

- It has an intense orange color when it passes into the urine and will permanently stain anything it touches, so it is imperative to warn patients of this.

- The most common side effects are dizziness, headache, and nausea.

- It is not an antibiotic but a topical analgesic.

- Since it only provides symptomatic relief and can build up in the body, it is not usually recommended for more than 3 consecutive days.

- Phenazopyridine should not be used in patients with known glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency as it can lead to hemolysis.[54]

Calcium Glycerophosphate

- This over-the-counter medication purports to reduce urinary acidity to help relieve dysuria.

- Although it appears to help with dysuria in at least some patients, there are no published randomized studies on its efficacy; therefore, evidence on the product is purely anecdotal.

- It is officially classified as a "medical food" and was initially designed to treat interstitial cystitis.

- It can be sprinkled over food or taken as a tablet at mealtime.

- The dietary recommendations are essentially the same as for interstitial cystitis.

Hydration

- Many patients with dysuria tend to drink less, so they will have to void less often; however, this tends to increase urinary concentrations, leading to worse burning.

- The optimal 24-hour urinary volume should be at least 2000 mL.

- Patients should be encouraged to drink more, not less.

Doxycycline

- Doxycycline is a tetracycline-based antibiotic with a unique spectrum of activity that includes many unusual and uncommon organisms.

- A trial of doxycycline can be used if it has not previously been used.

- A clinical trial of this antibiotic may cure some patients of otherwise intractable dysuria from an unusual organism.[55]

Azithromycin

- A trial of azithromycin can be used as Mycoplasma genitalium is a common cause of persistent or intractable urethritis.[43]

Estrogen Cream

- A clinical trial of estrogen cream in postmenopausal women is a reasonable therapy, as at least some patients will benefit.[56]

Other

- Other dysuria treatments include:[57]

- Acupuncture

- Alpha-blockers

- Behavioral therapy

- Biofeedback

- Botox injections

- Hypnosis

- Intravesical instillation of anti-inflammatory cocktails, more frequently used in interstitial cystitis (may include antibiotics, dimethyl sulfoxide, heparin, lidocaine, sodium bicarbonate, and steroids)

- Meditation

- Muscle relaxants

- Neuropathic pain medication (gabapentin)

- Topical anesthetics

- Tricyclic antidepressants (eg, amitriptyline)

- Urothelial barrier protection enhancement drugs (eg, pentosan polysulfate and intravesical heparin installations)

- Intravesical gentamicin plus betamethasone has also been reported to benefit some dysuria patients.[58]

- Tolterodine can act as both a bladder antispasmodic and anesthetic.

- An oral combination of atropine, hyoscyamine, methenamine, methylene blue, phenyl salicylate, and benzoic acid is another option.

- It has mildly anesthetic and antispasmodic effects.

- It also will inhibit bacterial growth.

- It gives the urine a blue-green color.

(A1)

There is generally no specific surgical treatment for dysuria, but Nd:YAG laser ablation has shown some promise in carefully selected female patients with symptoms refractory to medical therapy. Laser ablation of squamous metaplasia of the trigone and bladder neck areas has demonstrated success in some patients with trigonitis.[59] The initial necrotic tissue coagulation immediately after laser ablation is followed by the regrowth of normal urothelium.[59](A1)

Summary of Dysuria Treatments

- Alpha-blockers and overactive bladder medications (mirabegron, oxybutynin, trospium, etc)

- Amitriptyline

- Antibiotics as appropriate for UTIs, urethritis, and/or prostatitis

- Dietary therapy (avoidance of alcohol, caffeine, hot spices, processed and high-potassium foods)

- Female urethral dilation

- Gabapentin

- Intravesical instillations

- Pentosan polysulfate

- Second-line antibiotics (doxycycline, azithromycin)

- Sertraline

- Symptomatic therapy (phenazopyridine, calcium glycerophosphate, and similar)

- Third-line antibiotics (moxifloxacin)

- Vaginal estrogen for atrophic vaginitis

- Vaginitis therapy (metronidazole, miconazole, fluconazole, etc)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses are broadly divided into 2 categories: inflammatory and noninflammatory.[2][60]

Inflammatory

- Infectious causes: Cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis, STIs

- In females, vulvovaginitis and cervicitis can be causes of dysuria; in males, dysuria can result from prostatitis and epididymo-orchitis.

- Dermatologic causes: Contact dermatitis, psoriasis, Behcet syndrome, lichen sclerosis, lichen planus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- Noninfectious causes: Stone, a urethral or ureteral stent, pudendal neuralgia

Noninflammatory

- Trauma: Foreign body, surgery, urinary tract instrumentation, pelvic radiation

- Endocrine: Atrophic vaginitis, endometriosis

- Drugs: Cyclophosphamide, ketamine

- Anatomic: Benign prostatic hypertrophy, urethral stricture

- Neoplastic: Renal cell cancer, bladder cancer, lymphoma, vaginal cancer, vulvar cancer, prostate cancer, penile cancer, metastatic cancer

- Idiopathic: Interstitial cystitis, urethral pain syndrome

Prognosis

The prognosis for dysuria depends on its cause. Most of the etiologies of dysuria, including inflammatory and noninflammatory, demonstrate an excellent long-term prognosis, but early detection and treatment of the underlying causes of the dysuria are essential.

- Sepsis due to UTIs can lead to higher morbidity and mortality than systemic infections of other organs or systems, although urosepsis still has a better overall prognosis.[61]

- Long-term complications can occur due to stones, chronic infections, or benign prostatic hypertrophy, potentially leading to renal failure and, in severe cases, end-stage renal disease.

- During pregnancy, both maternal and fetal complications can arise if UTIs do not receive treatment timely and adequately.[9]

- The prognosis for dysuria occurring from neoplastic causes like renal or bladder cancers depends on the stage and type of cancer when diagnosed.

- Early diagnosis and quick follow-up with adequate treatment yield a good prognosis, whereas a delayed diagnosis is associated with higher recurrence and a poor prognosis.[62]

Complications

Depending on the cause of dysuria, short-term complications can include acute renal failure, development of systemic infection and sepsis, acute anemia from hematuria, urethral strictures with urinary retention, and emergent hospitalizations. Long-term complications include end-stage renal disease, infertility, long-term disability from recurrent infections, strictures or urinary tract cancers, and death from severe systemic infections or advanced urinary tract cancers. Patients with complicated UTIs can develop recurrences with expanded antibiotic resistance, leading to higher rates of hospitalizations and increased morbidity and mortality.[63]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial in preventing recurrent cases of dysuria.

Recurrent UTIs or Vaginitis

- Women who have dysuria due to recurrent UTIs or vaginitis should be educated not to use douches, maintain good perineal hygiene, use correct wiping techniques, and consider using D-mannose, methenamine, or nightly low-dose nitrofurantoin for prophylaxis.[64]

- Patients with recurrent UTIs due to uncontrolled diabetes should be educated about controlling their blood sugars.

Recurrent STIs

- Patients who are experiencing recurrent STIs should be educated about safe sex practices, the use of condoms, and urinating soon after sex.

Atrophic Vaginitis

- Patients with dysuria from atrophic vaginitis can benefit from education and hormone replacement therapy.

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

- Male patients suspected of having dysuria from benign prostatic hypertrophy should be educated about routine prostate exams and taking medications to control the related urinary symptoms.

All patients should understand the importance of early detection and treatment of infections, which can present with dysuria as the earliest sign, and should be encouraged to seek proper treatment and follow-up.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing patient-centered care and improving outcomes for dysuria necessitates a multidisciplinary approach involving various healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, and others. Accurate diagnosis is paramount in dysuria management. Healthcare professionals must employ thorough assessment techniques, including physical examinations, urinalysis, medical history review, and, at times, imaging. Diagnosis and management can include specialists from several different disciplines. Nurses can serve as primary contacts for patient questions and offer counsel; pharmacists can help with medication recommendations, check for interactions, and counsel the patient on proper dosing and administration. All healthcare team members must collaborate and function as a unit.

Prompt multidisciplinary care will help discover the underlying cause, allowing earlier, proper treatment and better patient outcomes. Involving patients in decision-making regarding their care fosters a patient-centered approach. Healthcare professionals should discuss treatment options, risks, and benefits with patients, allowing them to make informed choices.

Optimizing patient care and team performance in dysuria management requires a multidisciplinary approach where the interprofessional team collaborates seamlessly. Increasing efficiency and reducing unnecessary testing is essential to meeting best practice goals. By working together and focusing on patient-centered care, the interprofessional team can improve outcomes and provide more effective support to individuals experiencing dysuria.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

. Dysuria: What You Should Know About Burning or Stinging with Urination. American family physician. 2015 Nov 1:92(9):Online [PubMed PMID: 26554482]

Michels TC, Sands JE. Dysuria: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis in Adults. American family physician. 2015 Nov 1:92(9):778-86 [PubMed PMID: 26554471]

Geerlings SE. Clinical Presentations and Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiology spectrum. 2016 Oct:4(5):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0002-2012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27780014]

Stamm WE. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: progress and problems. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1999 Mar:179 Suppl 2():S380-3 [PubMed PMID: 10081511]

Gaydos C, Maldeis NE, Hardick A, Hardick J, Quinn TC. Mycoplasma genitalium compared to chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomonas as an aetiological agent of urethritis in men attending STD clinics. Sexually transmitted infections. 2009 Oct:85(6):438-40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035477. Epub 2009 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 19383597]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHorner P, Blee K, O'Mahony C, Muir P, Evans C, Radcliffe K, Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2015 UK National Guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2016 Feb:27(2):85-96. doi: 10.1177/0956462415586675. Epub 2015 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 26002319]

Black V, Magooa P, Radebe F, Myers M, Pillay C, Lewis DA. The detection of urethritis pathogens among patients with the male urethritis syndrome, genital ulcer syndrome and HIV voluntary counselling and testing clients: should South Africa's syndromic management approach be revised? Sexually transmitted infections. 2008 Aug:84(4):254-8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.028464. Epub 2008 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 18192290]

Miklovic T, Davis P. Dysuria, Rebound Tenderness, and a Palpable Mass-A Ticking Time Bomb. Military medicine. 2023 Mar 20:188(3-4):e882-e884. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab180. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33929544]

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, Wrenn K. Dysuria, Frequency, and Urgency. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250134]

Sinnott JD, Howlett DC. Urinary frequency and dysuria in an older woman. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2016 Sep 13:354():i4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4587. Epub 2016 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 27625371]

Rees J, Abrahams M, Doble A, Cooper A, Prostatitis Expert Reference Group (PERG). Diagnosis and treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a consensus guideline. BJU international. 2015 Oct:116(4):509-25. doi: 10.1111/bju.13101. Epub 2015 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 25711488]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHorner PJ, Taylor-Robinson D. Association of Mycoplasma genitalium with balanoposthitis in men with non-gonococcal urethritis. Sexually transmitted infections. 2011 Feb:87(1):38-40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.044487. Epub 2010 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 20852310]

Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, Jones R, Warner G, Moore M, Lowes JA, Smith H, Hawke C, Leydon G, Mullee M. Validating the prediction of lower urinary tract infection in primary care: sensitivity and specificity of urinary dipsticks and clinical scores in women. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2010 Jul:60(576):495-500. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X514747. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20594439]

Bellazreg F, Abid M, Lasfar NB, Hattab Z, Hachfi W, Letaief A. Diagnostic value of dipstick test in adult symptomatic urinary tract infections: results of a cross-sectional Tunisian study. The Pan African medical journal. 2019:33():131. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.33.131.17190. Epub 2019 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 31558930]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOrellana MA, Gómez-Lus ML, Lora D. Sensitivity of Gram stain in the diagnosis of urethritis in men. Sexually transmitted infections. 2012 Jun:88(4):284-7. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050150. Epub 2012 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 22308534]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRietmeijer CA, Mettenbrink CJ. Recalibrating the Gram stain diagnosis of male urethritis in the era of nucleic acid amplification testing. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2012 Jan:39(1):18-20. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182354da3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22183839]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKwan B, Ryder N, Knight V, Kenigsberg A, McNulty A, Read P, Bourne C. Sensitivity of 20-minute voiding intervals in men testing for Chlamydia trachomatis. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2012 May:39(5):405-6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318248a563. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22504609]

Artero A, Esparcia A, Eiros JM, Madrazo M, Alberola J, Nogueira JM. Effect of Bacteremia in Elderly Patients With Urinary Tract Infection. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2016 Sep:352(3):267-71. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.05.031. Epub 2016 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 27650231]

Wagenlehner FM, Brockmeyer NH, Discher T, Friese K, Wichelhaus TA. The Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2016 Jan 11:113(1-02):11-22. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26931526]

Ateya A, Fayez A, Hani R, Zohdy W, Gabbar MA, Shamloul R. Evaluation of prostatic massage in treatment of chronic prostatitis. Urology. 2006 Apr:67(4):674-8 [PubMed PMID: 16566972]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceComploj E, Trenti E, Palermo S, Pycha A, Mian C. Urinary cytology in bladder cancer: why is it still relevant? Urologia. 2015 Oct-Dec:82(4):203-5. doi: 10.5301/uro.5000129. Epub 2015 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 26219472]

Brisbane W, Bailey MR, Sorensen MD. An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques. Nature reviews. Urology. 2016 Nov:13(11):654-662. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.154. Epub 2016 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 27578040]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeGeorge KC, Holt HR, Hodges SC. Bladder Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2017 Oct 15:96(8):507-514 [PubMed PMID: 29094888]

Bremnor JD, Sadovsky R. Evaluation of dysuria in adults. American family physician. 2002 Apr 15:65(8):1589-96 [PubMed PMID: 11989635]

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, Van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A, Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003 Jan:61(1):37-49 [PubMed PMID: 12559262]

Taniguchi Y, Nishikawa H, Karashima T, Yoshinaga Y, Fujimoto S, Terada Y. Frequency of reactive arthritis, uveitis, and conjunctivitis in Japanese patients with bladder cancer following intravesical BCG therapy: A 20-year, two-centre retrospective study. Joint bone spine. 2017 Oct:84(5):637-638. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.09.014. Epub 2016 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 27825571]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSaricaoglu EM, Hasanoglu I, Guner R. The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. Journal of medical virology. 2021 Jan:93(1):192-193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26296. Epub 2020 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 32652541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYokogawa N, Minematsu N, Katano H, Suzuki T. Case of acute arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2021 Jun:80(6):e101. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218281. Epub 2020 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 32591356]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOno K, Kishimoto M, Shimasaki T, Uchida H, Kurai D, Deshpande GA, Komagata Y, Kaname S. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD open. 2020 Aug:6(2):. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001350. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32763956]

Carter JD, Hudson AP. Reactive arthritis: clinical aspects and medical management. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 2009 Feb:35(1):21-44. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.03.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19480995]

Kvien TK, Gaston JS, Bardin T, Butrimiene I, Dijkmans BA, Leirisalo-Repo M, Solakov P, Altwegg M, Mowinckel P, Plan PA, Vischer T, EULAR. Three month treatment of reactive arthritis with azithromycin: a EULAR double blind, placebo controlled study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2004 Sep:63(9):1113-9 [PubMed PMID: 15308521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBardin T, Enel C, Cornelis F, Salski C, Jorgensen C, Ward R, Lathrop GM. Antibiotic treatment of venereal disease and Reiter's syndrome in a Greenland population. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1992 Feb:35(2):190-4 [PubMed PMID: 1734908]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLaasila K, Laasonen L, Leirisalo-Repo M. Antibiotic treatment and long term prognosis of reactive arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003 Jul:62(7):655-8 [PubMed PMID: 12810429]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePutschky N, Pott HG, Kuipers JG, Zeidler H, Hammer M, Wollenhaupt J. Comparing 10-day and 4-month doxycycline courses for treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis-reactive arthritis: a prospective, double-blind trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2006 Nov:65(11):1521-4 [PubMed PMID: 17038453]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBarry HC, Ebell MH, Hickner J. Evaluation of suspected urinary tract infection in ambulatory women: a cost-utility analysis of office-based strategies. The Journal of family practice. 1997 Jan:44(1):49-60 [PubMed PMID: 9010371]

Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2015 Jun 5:64(RR-03):1-137 [PubMed PMID: 26042815]

Garcia MR, Leslie SW, Wray AA. Sexually Transmitted Infections. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809643]

Manhart LE, Gillespie CW, Lowens MS, Khosropour CM, Colombara DV, Golden MR, Hakhu NR, Thomas KK, Hughes JP, Jensen NL, Totten PA. Standard treatment regimens for nongonococcal urethritis have similar but declining cure rates: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 Apr:56(7):934-42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1022. Epub 2012 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 23223595]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSeña AC, Lensing S, Rompalo A, Taylor SN, Martin DH, Lopez LM, Lee JY, Schwebke JR. Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in men with nongonococcal urethritis: predictors and persistence after therapy. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012 Aug 1:206(3):357-65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis356. Epub 2012 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 22615318]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWikström A, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: a common cause of persistent urethritis among men treated with doxycycline. Sexually transmitted infections. 2006 Aug:82(4):276-9 [PubMed PMID: 16877573]

Mena LA, Mroczkowski TF, Nsuami M, Martin DH. A randomized comparison of azithromycin and doxycycline for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium-positive urethritis in men. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009 Jun 15:48(12):1649-54. doi: 10.1086/599033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19438399]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWeinstein SA, Stiles BG. Recent perspectives in the diagnosis and evidence-based treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2012 Apr:10(4):487-99. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22512757]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceManhart LE, Broad JM, Golden MR. Mycoplasma genitalium: should we treat and how? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Dec:53 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S129-42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir702. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22080266]

Wetmore CM, Manhart LE, Lowens MS, Golden MR, Whittington WL, Xet-Mull AM, Astete SG, McFarland NL, McDougal SJ, Totten PA. Demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of men with nongonococcal urethritis differ by etiology: a case-comparison study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2011 Mar:38(3):180-6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182040de9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21285914]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIto S, Hatazaki K, Shimuta K, Kondo H, Mizutani K, Yasuda M, Nakane K, Tsuchiya T, Yokoi S, Nakano M, Ohinishi M, Deguchi T. Haemophilus influenzae Isolated From Men With Acute Urethritis: Its Pathogenic Roles, Responses to Antimicrobial Chemotherapies, and Antimicrobial Susceptibilities. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017 Apr:44(4):205-210. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000573. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28282645]

Bader MS, Hawboldt J, Brooks A. Management of complicated urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Postgraduate medicine. 2010 Nov:122(6):7-15. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.11.2217. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21084776]

Coker TJ, Dierfeldt DM. Acute Bacterial Prostatitis: Diagnosis and Management. American family physician. 2016 Jan 15:93(2):114-20 [PubMed PMID: 26926407]

Shafi H, Moazzami B, Pourghasem M, Kasaeian A. An overview of treatment options for urinary stones. Caspian journal of internal medicine. 2016 Winter:7(1):1-6 [PubMed PMID: 26958325]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeslie SW, Sajjad H, Murphy PB. Renal Calculi, Nephrolithiasis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723043]

Patti L, Leslie SW. Acute Renal Colic. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613743]

Edelstein H, McCabe RE. Perinephric abscess. Modern diagnosis and treatment in 47 cases. Medicine. 1988 Mar:67(2):118-31 [PubMed PMID: 3352513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTanguay S, Awde M, Brock G, Casey R, Kozak J, Lee J, Nickel JC, Saad F. Diagnosis and management of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2009 Jun:3(3 Suppl 2):S92-S100 [PubMed PMID: 19543429]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeslie SW, Antolak S, Feloney MP, Soon-Sutton TL. Pudendal Neuralgia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965917]

Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of G6PD deficiency. American family physician. 2005 Oct 1:72(7):1277-82 [PubMed PMID: 16225031]

Phillip H, Okewole I, Chilaka V. Enigma of urethral pain syndrome: why are there so many ascribed etiologies and therapeutic approaches? International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2014 Jun:21(6):544-8. doi: 10.1111/iju.12396. Epub 2014 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 24447292]

YOUNGBLOOD VH, TOMLIN EM, WILLIAMS JO. Senile urethritis in women. Gynaecologia. International monthly review of obstetrics and gynecology. Revue internationale mensuelle d'obstetrique et de gynecologie. Monatsschrift fur Geburtshilfe und Gynakologie. 1960:149(Suppl):76-9 [PubMed PMID: 13846661]

Cakici ÖU, Hamidi N, Ürer E, Okulu E, Kayigil O. Efficacy of sertraline and gabapentin in the treatment of urethral pain syndrome: retrospective results of a single institutional cohort. Central European journal of urology. 2018:71(1):78-83. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2018.1574. Epub 2017 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 29732211]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePalleschi G, Carbone A, Ripoli A, Silvestri L, Petrozza V, Zanello PP, Pastore AL. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of Cistiquer in improving lower urinary tract symptoms in females with urethral syndrome. Minerva urologica e nefrologica = The Italian journal of urology and nephrology. 2014 Dec:66(4):225-32 [PubMed PMID: 25034330]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCostantini E, Zucchi A, Del Zingaro M, Mearini L. Treatment of urethral syndrome: a prospective randomized study with Nd:YAG laser. Urologia internationalis. 2006:76(2):134-8 [PubMed PMID: 16493214]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFERGUSON JD. The differential diagnosis of dysuria. The Practitioner. 1952 Oct:169(1012):458-61 [PubMed PMID: 13003775]

Qiang XH, Yu TO, Li YN, Zhou LX. Prognosis Risk of Urosepsis in Critical Care Medicine: A Prospective Observational Study. BioMed research international. 2016:2016():9028924. doi: 10.1155/2016/9028924. Epub 2016 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 26955639]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYaxley JP. Urinary tract cancers: An overview for general practice. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2016 Jul-Sep:5(3):533-538. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.197258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28217578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBleidorn J, Hummers-Pradier E, Schmiemann G, Wiese B, Gágyor I. Recurrent urinary tract infections and complications after symptomatic versus antibiotic treatment: follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. German medical science : GMS e-journal. 2016:14():Doc01. doi: 10.3205/000228. Epub 2016 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 26909012]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAggarwal N, Leslie SW, Lotfollahzadeh S. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491411]