Introduction

Uterine fibroids or leiomyomata are the most common benign tumor affecting women. An early 2003 study by Baird et al. showed that the estimated incidence of fibroids in women by age 50 was 70% for white women and reached over 80% black women.[1] Fibroids originate from uterine smooth muscle cells (myometrium) whose growth is primarily dependent on the levels of circulating estrogen. Further information regarding the pathogenesis of fibroids is poorly understood. Fibroids can either present as an asymptomatic incidental finding on imaging, or symptomatically. Common symptoms include abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, disruption of surrounding pelvic structures(bowel and bladder), and back pain. Uterine fibroids typically are seen in three significant locations: subserosal (outside the uterus), intramural (inside the myometrium), and submucosal (Inside the uterine cavity). They can further be broken down to pedunculated or not. Fibroids are classically diagnosed by physical exam and ultrasound imaging, which carries a high sensitivity for this pathology. Fibroids continue to be the leading indication for hysterectomy. According to De La Cruz et al., leiomyomata account for 39% of all hysterectomies annually.[2] This pathology places a financial burden on health care costs in the US. According to Cardozo et al., in 2013, the estimated cost for the US due to uterine fibroids was between $5.9 to $34.4 billion annually.[3] The expectation is that this number will continue to grow in the coming years.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact pathophysiology behind the development of uterine fibroids is unclear.[4] Research suggests that the starting event for fibroid development begins with a single uterine smooth muscle cell(myometrium), which is then followed by deviations from the normal signaling pathways of cellular division.[5] Fibroids are considered to be estrogen-dependent tumors, and there is evidence showing that leiomyomas overexpress certain estrogen and progesterone receptors when compared to normal surrounding myometrium.[6]

Epidemiology

Fibroids are rare before puberty; an article from Kim et al., states that there are no cases of fibroids before puberty.[7] Their likelihood increases as women age and, as mentioned above, can reach as high as 80% in some women before menopause.

Due to the pathology of fibroids, the majority of major risk factors include those that increase the exposure to higher levels of endogenous estrogen. Certain risk factors include early menarche, nulliparity, obesity, and late entry into menopause, and a positive family history of uterine fibroids. The most significant non-modifiable risk factor is African descent, which leads to earlier diagnosis and more severe symptoms. There is a decreased risk for uterine fibroids with increased parity, late menarche, smoking, and use of oral contraceptives.[8][9][2]

Pathophysiology

Fibroids are a result of the inappropriate growth of uterine smooth muscle tissue or myometrium. Their growth is dependent on estrogen and progesterone levels. The underlying pathophysiology is uncertain.

History and Physical

History and physical exam include a thorough menstrual history to determine the timing, quantity, and any potential aggravating factors for the abnormal bleeding. Common presenting symptoms include metrorrhagia, menorrhagia, or a combination of the two. Less common presenting symptoms include dyspareunia, pelvic pain, bowel problems, urinary symptoms, or signs and symptoms related to anemia. Most of the less frequent symptoms are a reflection of the mass effect produced by leiomyomas on surrounding structures. Patients may also be completely asymptomatic with an incidental finding of fibroids on imaging.

A speculum exam with a bimanual exam should be performed to rule out any vaginal or cervical pathology, as well as assess the size, and shape of the female reproductive organs. A large asymmetric uterus felt upon the exam is indicative of fibroids. Finally, consider evaluating for conjunctival pallor and thyroid pathology to identify potential secondary symptoms or causes of abnormal bleeding.

Evaluation

Laboratory studies

The initial evaluation should include a beta-human chorionic gonadotropin test to rule out pregnancy, CBC, TSH, and a prolactin level to evaluate for the non-structural causes in the differential(see below).

Include an endometrial biopsy for women over 35.

Radiologic studies

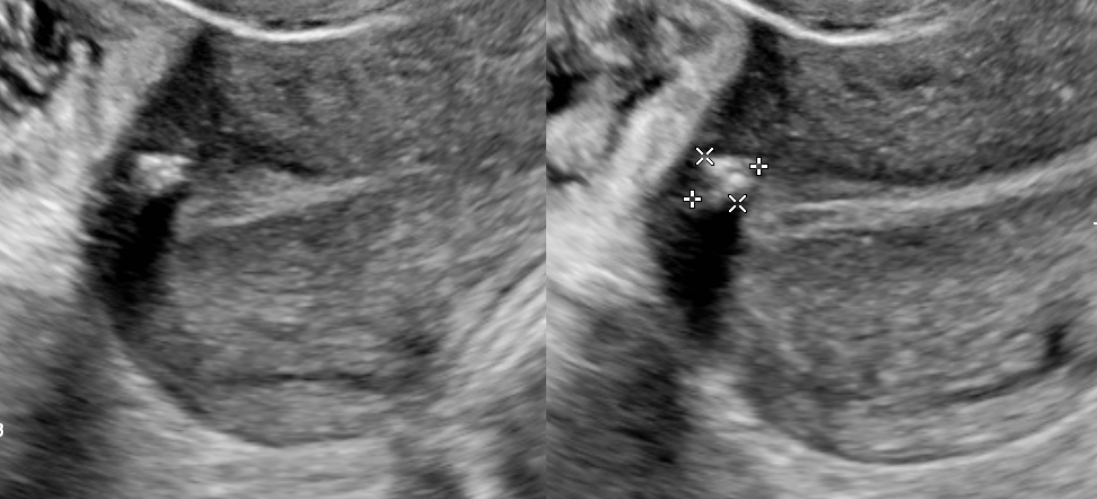

Transvaginal ultrasound is the gold standard for imaging uterine fibroids. It has a sensitivity of around 90 to 99% for the detection of uterine fibroids. Ultrasound can improve with the use of saline-infused sonography, which helps increase the sensitivity for the detection of subserosal and intramural fibromas.[2][10] Fibroid appearance is as a firm, well-circumscribed, hypoechoic mass. On ultrasound, tend to have a variable amount of shadowing, and calcifications or necrosis may distort the echogenicity.[11]

Hysteroscopy is where the physician uses a hysteroscope to visualize the inside of the uterus. This imaging modality allows for better visualization of fibroids inside the uterine cavity. This method allows for the direct removal of intrauterine growths during the procedure.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging MRI has the benefit of providing a better picture of the number, size, vascular supply, and boundaries of the fibroids as they relate to the pelvis. Nevertheless, it is unnecessary for a routine diagnosis when fibroids are suspected. It has not been shown to differentiate leiomyosarcoma from leiomyoma.[10]

Treatment / Management

While deciding on treatment options for uterine fibroids, the patient's age, presenting symptoms, and desire for fertility preservation all merit consideration. The locations and size of the fibroids will both determine the available treatment options.[2] Management options can be broken down into three categories starting at surveillance with progression to medical management or surgical therapy with increasing severity of symptoms.

Surveillance: This is the preferred method in women with asymptomatic fibroids. The current recommendations do not require serial imaging when following these patients.[2]

Medical Management: Primarily revolves around decreasing the severity of bleeding and pain symptoms.

- Hormonal contraceptives: This treatment group includes oral contraceptive pills (OCP) and the levonorgestrel intrauterine device(IUD). OCPs are common options in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding related to symptomatic fibroids. However, there is only limited data showing their effectiveness in uterine fibroids, and larger randomized controlled trials are necessary.[12][13][2] The levonorgestrel IUD is currently the recommended hormonal therapy for symptomatic fibroids due to the lack of systemic effects and low side effect profile.[14] Caution should is necessary when treating fibroids that distort the intrauterine cavity as they can lead to a higher rate of expulsion.

- GnRH Agonist (leuprolide): This method works by acting on the pituitary gland to decrease gonadal hormone production, thus decreasing the hormone-stimulated growth of the fibroid. A study by Friedman et al. showed a decrease in uterine size by 45% at 24 weeks of treatment on a GnRH agonist with a return to pretreatment size 24 weeks after cessation.[15] Long-term therapy with a GnRH agonist has also been shown to result in statistically significant bone loss. Because of this and its relatively short-term effect, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has recommended that it's use be limited to 6 months or less.[14][16][17] Leuprolide is most effective when used as a pre-surgical therapy for symptomatic fibroids.[13]

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Anti-inflammatories have been shown to decrease prostaglandin levels, which are elevated in women with heavy menstrual bleeding and are responsible for the painful cramping experienced in menstruation. They have not been shown to decrease the size of the fibroids.[18] (A1)

Other potential medical therapies include aromatase inhibitors, and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), such as raloxifene or tamoxifen. There is little evidence supporting the use of these medications in the treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroids.[13] Tranexamic acid has been approved for the treatment of abnormal and heavy uterine bleeding but has not been approved or shown to decrease the disease burden in uterine fibroids.[13][19]

Surgical Therapy:

- Endometrial Ablation. It offers an alternative to surgery in patients whose primary complaint is heavy or abnormal bleeding. There is a larger risk of a failed procedure with submucosal fibroids because they cause disruption of the uterine cavity and can prevent proper cauterization of the entire endometrium.

- Uterine Artery Embolization. A minimally invasive approach for those who wish to preserve fertility. This technique works by decreasing the total blood supply to the uterus, thereby decreasing the flow to the fibroids and minimizing bleeding symptoms. The procedure has been shown effective in controlling menorrhagia. However, according to De La Cruz et al., only limited studies show the effects on fertility preservation with this technique. [2]

- Myomectomy. An invasive surgical option for those who desire fertility preservation. There is no large randomized controlled trial showing that myomectomy can improve fertility for patients.[2][10] Furthermore, the outcome is highly dependent on the location and size of the fibroid.[8][20] Nevertheless, it can be an effective treatment option in those wishing to avoid hysterectomy.

- MRI guided focused ultrasound surgery. This treatment option utilizes MRI and ultrasound waves to focus on the fibroid, resulting in cauterization. As a relatively new treatment, there is not enough clinical evidence to support its long term effectiveness at this time.

- Hysterectomy. Remains the definitive treatment for fibroids.

Differential Diagnosis

Many other disease processes share the signs and symptoms of uterine leiomyomas, most of which are common etiologies of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) and pelvic pain. According to the Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the differential can be broken down into the classification system PALM-COEIN.[21][22] The mnemonic is grouped by structural and non-structural causes of AUB, which includes the following:

Polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy, coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial, iatrogenic, not yet classified.

Adenomyosis, in particular, has been shown to have a high rate of coexistence with uterine fibroids.[23] Unlike fibroids, adenomyosis tends to be more oval-shaped with indistinct margins on ultrasound. They do not typically display a mass effect.

It is essential to realize that leiomyosarcomas can present similar to leiomyomas. Brohl et al. concluded that sarcomas are diagnosed in presumed fibroids after surgery in 1 in 340 women. That number increases to 1 in 98 in women 75 to 79 years of age.[24] Although there is no reliable way to differentiate the two without biopsy, a few studies have identified factors that are associated with sarcoma which include but are not limited to postmenopausal status, a predominantly subserosal mass, solitary fibroid, rapid growth, and a T2-weighted signal heterogeneity on magnetic resonance imaging.[2][25]

Prognosis

Fibroids can be a complicated diagnosis to manage for any patient who desires pregnancy, may have limited access to healthcare or has one of the non-modifiable risk factors associated with the disease. While hormone and anti-inflammatory therapy can help to slow the progression of fibroids, the emphasis has been on improving outcomes with minimally invasive and fertility-preserving procedures.[10]

Complications

Although the exact impact of fibroids on fertility is unknown, there is an apparent correlation between fibroids and infertility that is dependent on the location and size of the fibroid. Research by Pritts et al. showed that submucosal fibroids resulted in decreased rates of implantation and pregnancy as well as increased rates of spontaneous miscarriage due to their distortion of the endometrium. But more recently, Purohit and Vigneswaran stated that this research showed no evidence to suggest subserosal fibroids had any effect on fertility.[26][8] Other complications include anemia, chronic pelvic pain, and sexual dysfunction.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients need to understand that the majority of the time fibroids are a benign pathology. Words, such as neoplasm, while describing fibroids can have a potentially harmful impact on the mental well-being of the patient. Furthermore, fibroids can carry a heavy burden of disease, which is implemented in its impact on future fertility and on the overall quality of life. Discussion and management of modifiable risk factors are important in the care of these patients. Although ideal minimally invasive therapies for the treatment of symptomatic fibroids theoretically exist, there is little evidence from large randomized controlled trials supporting positive long term outcomes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Prevention of fibroids may revolve around the identification and management of the modifiable risk factors. These include exercise, obesity, and diet.[27]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although fibroids are considered a benign diagnosis, they can exert a negative impact on the patient's mental and physical health. Emphasis should be placed on proper patient education while keeping in mind how the patient perceives the disease. In describing fibroids, words such as tumor or neoplasm should be used with caution by all members of the healthcare team to ensure the patient has a good understanding of the disease.

It is essential to identify or rule out more serious causes of abnormal uterine bleeding during the diagnostic workup for fibroids.

Treatment for patients should primarily begin with trials of NSAIDs and hormonal therapy only escalating when symptoms are refractory, or unmanageable by medication. Minimally invasive treatment options performed by gynecologists or interventional radiologists should be an option with the understanding there is promising, but few high-quality randomized controlled trials exist showing the effectiveness and long term outcomes. In cases where the treating clinician attempts medical management, they should consult a pharmacist to discuss agent selection, verify dosing, and avoid drug-drug interactions. Nursing staff can followup with the patient, assess therapy progress, check for medication adverse effects, and provide patient counseling, informing the rest of the team of any concerns.

Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment for leiomyomas and should be on reserve for patients with high severity of symptoms, who desire infertility. Specialized surgical nurses will be crucial in these cases, helping to prepare the patient, assisting during the procedure, and providing post-operative care and evaluation, as well as medication administration. Every member of the interprofessional healthcare team plays a role in the proper education for patients about the risks and outcomes of this major procedure.

Emphasizing interprofessional cooperation and effective communication in all members of the healthcare team will provide the best outcomes for patients with uterine fibroids. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jan:188(1):100-7 [PubMed PMID: 12548202]

De La Cruz MS, Buchanan EM. Uterine Fibroids: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2017 Jan 15:95(2):100-107 [PubMed PMID: 28084714]

Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Mar:206(3):211.e1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.002. Epub 2011 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 22244472]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOkolo S. Incidence, aetiology and epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2008 Aug:22(4):571-88. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.04.002. Epub 2008 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 18534913]

Townsend DE, Sparkes RS, Baluda MC, McClelland G. Unicellular histogenesis of uterine leiomyomas as determined by electrophoresis by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1970 Aug 15:107(8):1168-73 [PubMed PMID: 5458572]

Benassayag C, Leroy MJ, Rigourd V, Robert B, Honoré JC, Mignot TM, Vacher-Lavenu MC, Chapron C, Ferré F. Estrogen receptors (ERalpha/ERbeta) in normal and pathological growth of the human myometrium: pregnancy and leiomyoma. The American journal of physiology. 1999 Jun:276(6):E1112-8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.6.E1112. Epub [PubMed PMID: 10362625]

Kim JJ, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Progesterone action in endometrial cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and breast cancer. Endocrine reviews. 2013 Feb:34(1):130-62. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1043. Epub 2013 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 23303565]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePurohit P, Vigneswaran K. Fibroids and Infertility. Current obstetrics and gynecology reports. 2016:5():81-88 [PubMed PMID: 27217980]

Sabry M, Halder SK, Allah AS, Roshdy E, Rajaratnam V, Al-Hendy A. Serum vitamin D3 level inversely correlates with uterine fibroid volume in different ethnic groups: a cross-sectional observational study. International journal of women's health. 2013:5():93-100. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S38800. Epub 2013 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 23467803]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDonnez J, Dolmans MM. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Human reproduction update. 2016 Nov:22(6):665-686 [PubMed PMID: 27466209]

Woźniak A, Woźniak S. Ultrasonography of uterine leiomyomas. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2017 Dec:16(4):113-117. doi: 10.5114/pm.2017.72754. Epub 2017 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 29483851]

Venkatachalam S, Bagratee JS, Moodley J. Medical management of uterine fibroids with medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo Provera): a pilot study. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004 Oct:24(7):798-800 [PubMed PMID: 15763792]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLewis TD, Malik M, Britten J, San Pablo AM, Catherino WH. A Comprehensive Review of the Pharmacologic Management of Uterine Leiomyoma. BioMed research international. 2018:2018():2414609. doi: 10.1155/2018/2414609. Epub 2018 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 29780819]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Aug:112(2 Pt 1):387-400. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318183fbab. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18669742]

Friedman AJ, Hoffman DI, Comite F, Browneller RW, Miller JD. Treatment of leiomyomata uteri with leuprolide acetate depot: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. The Leuprolide Study Group. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1991 May:77(5):720-5 [PubMed PMID: 1901638]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSurrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 May:99(5 Pt 1):709-19 [PubMed PMID: 11978277]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGonzalez-Barcena D, Alvarez RB, Ochoa EP, Cornejo IC, Comaru-Schally AM, Schally AV, Engel J, Reissmann T, Riethmüller-Winzen H. Treatment of uterine leiomyomas with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist Cetrorelix. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 1997 Sep:12(9):2028-35 [PubMed PMID: 9363724]

Lethaby A, Duckitt K, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Jan 31:(1):CD000400. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000400.pub3. Epub 2013 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 23440779]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWellington K, Wagstaff AJ. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the management of menorrhagia. Drugs. 2003:63(13):1417-33 [PubMed PMID: 12825966]

Ezzati M, Norian JM, Segars JH. Management of uterine fibroids in the patient pursuing assisted reproductive technologies. Women's health (London, England). 2009 Jul:5(4):413-21. doi: 10.2217/whe.09.29. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19586433]

Marnach ML, Laughlin-Tommaso SK. Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019 Feb:94(2):326-335. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.12.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30711128]

Benetti-Pinto CL, Rosa-E-Silva ACJS, Yela DA, Soares Júnior JM. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2017 Jul:39(7):358-368. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603807. Epub 2017 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 28605821]

Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA. Adenomyosis: A Clinical Review of a Challenging Gynecologic Condition. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2016 Feb 1:23(2):164-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.09.018. Epub 2015 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26427702]

Brohl AS, Li L, Andikyan V, Običan SG, Cioffi A, Hao K, Dudley JT, Ascher-Walsh C, Kasarskis A, Maki RG. Age-stratified risk of unexpected uterine sarcoma following surgery for presumed benign leiomyoma. The oncologist. 2015 Apr:20(4):433-9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0361. Epub 2015 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 25765878]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen I, Firth B, Hopkins L, Bougie O, Xie RH, Singh S. Clinical Characteristics Differentiating Uterine Sarcoma and Fibroids. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2018 Jan-Mar:22(1):. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2017.00066. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29398899]

Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertility and sterility. 2009 Apr:91(4):1215-23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.051. Epub 2008 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 18339376]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017 Sep:124(10):1501-1512. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14640. Epub 2017 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 28296146]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence