Introduction

The cardiovascular system consists of the heart and blood vessels.[1] There is a wide array of problems that may arise within the cardiovascular system, for example, endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, abnormalities in the conduction system, among others, cardiovascular disease (CVD) or heart disease refer to the following 4 entities that are the focus of this article[2]:

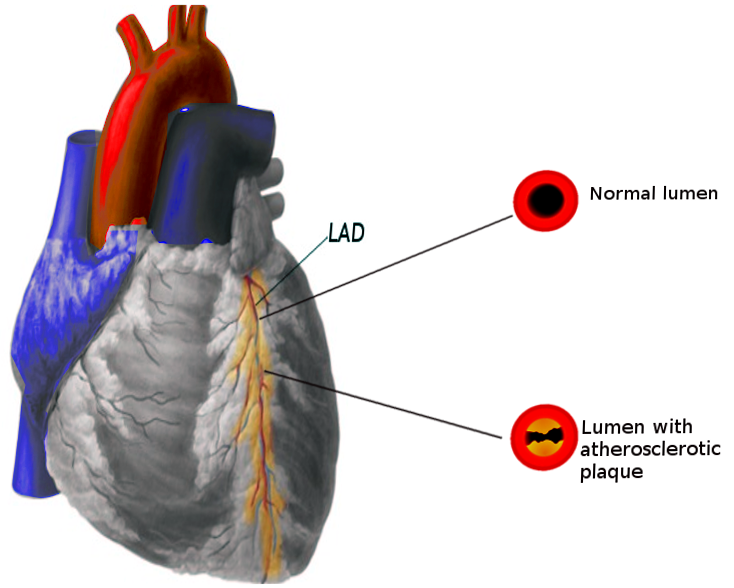

- Coronary artery disease (CAD): Sometimes referred to as Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), results from decreased myocardial perfusion that causes angina, myocardial infarction (MI), and/or heart failure. It accounts for one-third to one-half of the cases of CVD.

- Cerebrovascular disease (CVD): Including stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD): Particularly arterial disease involving the limbs that may result in claudication

- Aortic atherosclerosis: Including thoracic and abdominal aneurysms

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Although CVD may directly arise from different etiologies such as emboli in a patient with atrial fibrillation resulting in ischemic stroke, rheumatic fever causing valvular heart disease, among others, addressing risks factors associated to the development of atherosclerosis is most important because it is a common denominator in the pathophysiology of CVD.

The industrialization of the economy with a resultant shift from physically demanding to sedentary jobs, along with the current consumerism and technology-driven culture that is related to longer work hours, longer commutes, and less leisure time for recreational activities, may explain the significant and steady increase in the rates of CVD during the last few decades. Specifically, physical inactivity, intake of a high-calorie diet, saturated fats, and sugars are associated with the development of atherosclerosis and other metabolic disturbances like metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension that are highly prevalent in people with CVD.[3][2][4][5]

According to the INTERHEART study that included subjects from 52 countries, including high, middle, and low-income countries, 9 modifiable risks factors accounted for 90% of the risk of having a first MI: smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, psychosocial factors, consumption of fruits and vegetables, regular alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity. It is important to mention that in this study 36% of the population-attributable risk of MI was accounted to smoking.[6]

Other large cohort studies like the Framingham Heart Study[7] and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III)[5] have also found a strong association and predictive value of dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, smoking, and glucose intolerance. Sixty percent to 90% of CHD events occurred in subjects with at least one risk factor.

These findings have been translated into health promotion programs by the American Heart Association with emphasis on seven recommendations to decrease the risk of CVD: avoiding smoking, being physically active, eating healthy, and keeping normal blood pressure, body weight, glucose, and cholesterol levels.[8][9]

On the other hand, non-modifiable factors as family history, age, and gender have different implications.[4][7] Family history, particularly premature atherosclerotic disease defined as CVD or death from CVD in a first-degree relative before 55 years (in males) or 65 years (in females) is considered an independent risk factor.[10] There is also suggestive evidence that the presence of CVD risk factors may differently influence gender.[4][7] For instance, diabetes and smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day had increased CVD risk in women compared to men.[11] Prevalence of CVD increases significantly with each decade of life.[12]

The presence of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus),[13] history of mediastinal or chest wall radiation,[14] microalbuminuria,[15], increased inflammatory markers[16][17] have also been associated with an increased rate and incidence of CVD.

Pointing out specific diet factors like meat consumption, fiber, and coffee and their relation to CVD remains controversial due to significant bias and residual confounding encountered in epidemiological studies.[18][19]

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain among the 2 leading causes of death in the United States since 1975 with 633,842 deaths or 1 in every 4 deaths, heart disease occupied the leading cause of death in 2015 followed by 595,930 deaths related to cancer.[2] CVD is also the number 1 cause of death globally with an estimated 17.7 million deaths in 2015, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The burden of CVD further extends as it is considered the most costly disease even ahead of Alzheimer disease and diabetes with calculated indirect costs of $237 billion dollars per year and a projected increased to $368 billion by 2035.[20]

Although the age-adjusted rate and acute mortality from MI have been declining over time, reflecting the progress in diagnosis and treatment during the last couple of decades, the risk of heart disease remains high with a calculated 50% risk by age 45 in the general population.[7][21] The incidence significantly increases with age with some variations between genders as the incidence is higher in men at younger ages.[2] The difference in incidence narrows progressively in the post-menopausal state.[2]

Pathophysiology

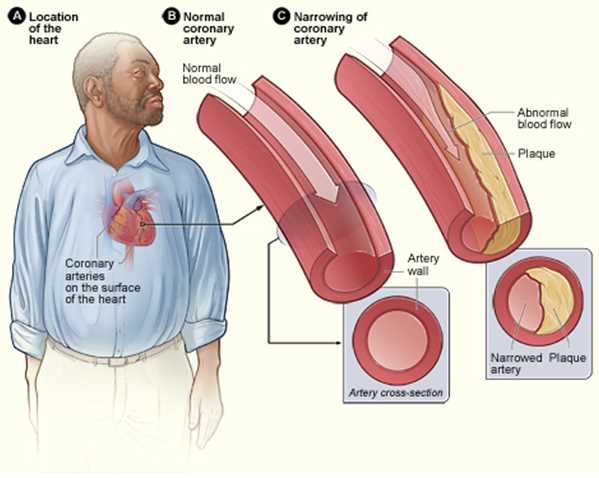

Atherosclerosis is the pathogenic process in the arteries and the aorta that can potentially cause disease as a consequence of decreased or absent blood flow from stenosis of the blood vessels.[22]

It involves multiple factors dyslipidemia, immunologic phenomena, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. These factors are believed to trigger the formation of fatty streak, which is the hallmark in the development of the atherosclerotic plaque[23]; a progressive process that may occur as early as in the childhood.[24] This process comprises intimal thickening with subsequent accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) and extracellular matrix, followed by aggregation and proliferation of smooth muscle cells constituting the formation of the atheroma plaque.[25] As this lesions continue to expand, apoptosis of the deep layers can occur, precipitating further macrophage recruitment that can become calcified and transition to atherosclerotic plaques.[26]

Other mechanisms like arterial remodeling and intra-plaque hemorrhage play an important role in the delay and accelerated the progression of atherosclerotic CVD but are beyond the purpose of this article.[27]

History and Physical

The clinical presentation of cardiovascular diseases can range from asymptomatic (e.g., silent ischemia, angiographic evidence of coronary artery disease without symptoms, among others) to classic presentations as when patients present with typical anginal chest pain consistent of myocardial infarction and/or those suffering from acute CVA presenting with focal neurological deficits of sudden onset.[28][29][28]

Historically, coronary artery disease typically presents with angina that is a pain of substernal location, described as a crushing or pressure in nature, that may radiate to the medial aspect of the left upper extremity, to the neck or the jaw and that can be associated with nausea, vomiting, palpitations, diaphoresis, syncope or even sudden death.[30] Physicians and other health care providers should be aware of possible variations in symptom presentation for these patients and maintain a high index of suspicion despite an atypical presentation, for example, dizziness and nausea as the only presenting symptoms in patients having an acute MI[31]), particularly in people with a known history of CAD/MI and for those with the presence of CVD risk factors.[32][33][34][33][32] Additional chest pain features suggestive of ischemic etiology are the exacerbation with exercise and or activity and resolution with rest or nitroglycerin.[35]

Neurologic deficits are the hallmark of cerebrovascular disease including TIA and stroke where the key differentiating factor is the resolution of symptoms within 24 hours for patients with TIA.[36] Although the specific symptoms depend on the affected area of the brain, the sudden onset of extremity weakness, dysarthria, and facial droop are among the most commonly reported symptoms that raise concern for a diagnosis of a stroke.[37][38] Ataxia, nystagmus and other subtle symptoms as dizziness, headache, syncope, nausea or vomiting are among the most reported symptoms with people with posterior circulation strokes challenging to correlate and that require highly suspicion in patients with risks factors.[39]

Patients with PAD may present with claudication of the limbs, described as a cramp-like muscle pain precipitated by increased blood flow demand during exercise that typically subsides with rest.[40] Severe PAD might present with color changes of the skin and changes in temperature.[41]

Most patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm will be asymptomatic, but symptoms can develop as it progresses from subtle symptoms from compression to surrounding tissues causing cough, shortness of breath or dysphonia, to the acute presentation of sudden crushing chest or back pain due to acute rupture.[42] The same is true for abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) that cause no symptoms in early stages to the acute presentation of sudden onset of abdominal pain or syncope from acute rupture.[43]

A thorough physical examination is paramount for the diagnosis of CVD. Starting with a general inspection to look for signs of distress as in patients with angina or with decompensated heart failure, or chronic skin changes from PAD. Carotid examination with the patient on supine position and the back at 30 degrees for the palpation and auscultation of carotid pulses, bruits and to evaluate for jugular venous pulsations on the neck is essential. Precordial examination starting with inspection, followed by palpation looking for chest wall tenderness, thrills, and identification of the point of maximal impulse should then be performed before auscultating the precordium. Heart sounds auscultation starts in the aortic area with the identification of the S1 and S2 sounds followed by characterization of murmurs if present. Paying attention to changes with inspirations and maneuvers to correctly characterize heart murmurs is encouraged. Palpating peripheral pulses with bilateral examination and comparison when applicable is an integral part of the CVD examination.[44]

Evaluation

Thorough clinical history and physical exam directed but not limited to the cardiovascular system are the hallmarks for the diagnosis of CVD. Specifically, a history compatible with obesity, angina, decreased exercise tolerance, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, syncope or presyncope, and claudication should prompt the clinician to obtain a more detailed history and physical exam and, if pertinent, obtain ancillary diagnostic test according to the clinical scenario (e.g., electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes for patients presenting with chest pain).

Besides a diagnosis prompted by clinical suspicion, most of the efforts should be oriented for primary prevention by targeting people with the presence of risk factors and treat modifiable risk factors by all available means. All patient starting at age 20 should be engaged in the discussion of CVD risk factors and lipid measurement.[9] Several calculators that use LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol levels and the presence of other risk factors calculate a 10-year or 30-year CVD score to determine if additional therapies like the use of statins and aspirin are indicated for primary prevention, generally indicated if such risk is more than ten percent.[10] Like other risk assessment tools, the use of this calculators have some limitations, and it is recommended to exert precaution when assessing patients with diabetes and familial hypercholesterolemia as their risk can be underestimated. Another limitation to their use is that people older than 79 were usually excluded from the cohorts where these calculators were formulated, and individualized approach for these populations is recommended by discussing risk and benefits of adjunctive therapies and particular consideration of life expectancy. Some experts recommend a reassessment of CVD risk every 4 to 6 years.[9]

Preventative measures like following healthy food habits, avoiding overweight and following an active lifestyle are pertinent in all patients, particularly for people with non-modifiable risk factors such as family history of premature CHD or post-menopause.[9][8]

The use of inflammatory markers and other risk assessment methods as coronary artery calcification score (CAC) are under research and have limited applications that their use should not replace the identification of people with known risk factors, nonetheless these resources remain as promising tools in the future of primary prevention by detecting people with subclinical atherosclerosis at risk for CVD.[45]

Treatment / Management

Management of CVD is very extensive depending on the clinical situation (catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke, angioplasty for peripheral vascular disease, coronary stenting for CHD); however, patients with known CVD should be strongly educated on the need for secondary prevention by risk factor and lifestyle modification.[9][46](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute pericarditis

- Angina pectoris

- Artherosclerosis

- Coronary artery vasospasm

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Giant cell arteritis

- Hypertension

- Hypertensive heart disease

- Kawasaki disease

- Myocarditis

Prognosis

The prognosis and burden of CVD have been discussed in other sections.

Complications

The most feared complication from CVD is death and, as explained above, despite multiple discoveries in the last decades CVD remains in the top leading causes of death all over the world owing to the alarming prevalence of CVD in the population.[2] Other complications as the need for longer hospitalizations, physical disability and increased costs of care are significant and are the focus for health-care policymakers as it is believed they will continue to increase in the coming decades.[20]

For people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFreEF) of less than 35%, as the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias is exceedingly high in these patients, current guidelines recommend the implantation of an implantable-cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for those with symptoms equivalent to a New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II-IV despite maximal tolerated medical therapy.[47]

Strokes can leave people with severe disabling sequelae like dysarthria or aphasia, dysphagia, focal or generalized muscle weakness or paresis that can be temporal or cause permanent physical disability that may lead to a complete bedbound state due to hemiplegia with added complications secondary to immobility as is the higher risk of developing urinary tract infections and/or risk for thromboembolic events.[48][49]

There is an increased risk of all-cause death for people with PAD compared to those without evidence of peripheral disease.[50] Chronic wounds, physical limitation, and limb ischemia are among other complications from PAD.[51]

Consultations

An interprofessional approach that involves primary care doctors, nurses, dietitians, cardiologists, neurologists, and other specialists is likely to improve outcomes. This has been shown to be beneficial in patients with heart failure,[52] coronary disease,[53] and current investigations to assess the impact on other forms of CVD are under planning and promise encouraging results.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Efforts should be directed toward primary prevention by leading a healthy lifestyle, and an appropriate diet starting as early as possible with the goal of delay or avoid the initiation of atherosclerosis as it relates to the future risk of CVD. The AHA developed the concept of "ideal cardiovascular health" defined by the presence of[8]:

- Ideal health behaviors: Nonsmoking, body mass index less than 25 kg/m2, physical activity at goal levels, and the pursuit of a diet consistent with current guideline recommendations

- Ideal health factors: Untreated total cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL, untreated blood pressure less than 120/80 mm Hg, and fasting blood glucose less than 100 mg/dL) with the goal to improve the health of all Americans with an expected decrease in deaths from CVD by 20%

Specific attention should be made to people at higher risk for CVD as are people with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smokers, and obese patients. Risk factors modification by controlling their medical conditions, avoiding smoking, taking appropriate measures to lose weight and maintaining an active lifestyle is of extreme importance.[8][9][10] The recommendations on the use of statins and low-dose aspirin for primary and secondary prevention has been discussed in other sections.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cardiovascular disease generally refers to 4 general entities: CAD, CVD, PVD, and aortic atherosclerosis.

CVD is the main cause of death globally.

Measures aimed to prevent the progression of atherosclerosis are the hallmark for primary prevention of CVD.

Risk factor and lifestyle modification are paramount in the prevention of CVD.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional and patient-oriented approach can help to improve outcomes for people with cardiovascular disease as shown in patients with heart failure (HF) who had better outcomes when the interprofessional involvement of nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, and other health professionals was used (Class 1A).[52]

Similarly, positive results were obtained in people in an intervention group who were followed by an interprofessional team comprised of pharmacists, nurses and a team of different physicians. This group had a reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD by 76% compared to the control group.[53] Healthcare workers should educate the public on lifestyle changes and reduce the modifiable risk factors for heart disease to a minimum.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Farley A, McLafferty E, Hendry C. The cardiovascular system. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2012 Oct 31-Nov 6:27(9):35-9 [PubMed PMID: 23240514]

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 Mar 20:137(12):e67-e492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. Epub 2018 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 29386200]

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB. Risk Assessment for Cardiovascular Disease With Nontraditional Risk Factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 Jul 17:320(3):272-280. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8359. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29998297]

Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, Levy D, Meigs JB, D'Agostino RB Sr, Wilson PW, Savage PJ. Trends in cardiovascular complications of diabetes. JAMA. 2004 Nov 24:292(20):2495-9 [PubMed PMID: 15562129]

Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Wilson PW, Sempos CT, Sundström J, Kannel WB, Levy D, D'Agostino RB. Relative importance of borderline and elevated levels of coronary heart disease risk factors. Annals of internal medicine. 2005 Mar 15:142(6):393-402 [PubMed PMID: 15767617]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L, INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet (London, England). 2004 Sep 11-17:364(9438):937-52 [PubMed PMID: 15364185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFox CS, Pencina MJ, Wilson PW, Paynter NP, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB Sr. Lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease among individuals with and without diabetes stratified by obesity status in the Framingham heart study. Diabetes care. 2008 Aug:31(8):1582-4. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0025. Epub 2008 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 18458146]

Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD, American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010 Feb 2:121(4):586-613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. Epub 2010 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 20089546]

Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, Benjamin EJ, Budoff MJ, Fayad ZA, Foster E, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Kushner FG, Lauer MS, Shaw LJ, Smith SC Jr, Taylor AJ, Weintraub WS, Wenger NK, Jacobs AK, Smith SC Jr, Anderson JL, Albert N, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Halperin JL, Hochman JS, Kushner FG, Nishimura R, Ohman EM, Page RL, Stevenson WG, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010 Dec 14:56(25):e50-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21144964]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGoff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC Jr, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PW, Jordan HS, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC Jr, Tomaselli GF, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24:129(25 Suppl 2):S49-73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. Epub 2013 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 24222018]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNjølstad I, Arnesen E, Lund-Larsen PG. Smoking, serum lipids, blood pressure, and sex differences in myocardial infarction. A 12-year follow-up of the Finnmark Study. Circulation. 1996 Feb 1:93(3):450-6 [PubMed PMID: 8565161]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSavji N, Rockman CB, Skolnick AH, Guo Y, Adelman MA, Riles T, Berger JS. Association between advanced age and vascular disease in different arterial territories: a population database of over 3.6 million subjects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Apr 23:61(16):1736-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.054. Epub 2013 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 23500290]

Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Burtcel B, Maa JF, Hodder S. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2003 Aug 1:33(4):506-12 [PubMed PMID: 12869840]

Khouri MG, Douglas PS, Mackey JR, Martin M, Scott JM, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Jones LW. Cancer therapy-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer: addressing the unresolved issues. Circulation. 2012 Dec 4:126(23):2749-63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.100560. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23212997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Hallé JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, Nawaz S, Yusuf S, HOPE Study Investigators. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001 Jul 25:286(4):421-6 [PubMed PMID: 11466120]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEmerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, Pepys MB, Thompson SG, Collins R, Danesh J. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England). 2010 Jan 9:375(9709):132-40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7. Epub 2009 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 20031199]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003 Jan 28:107(3):499-511 [PubMed PMID: 12551878]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTrepanowski JF,Ioannidis JPA, Perspective: Limiting Dependence on Nonrandomized Studies and Improving Randomized Trials in Human Nutrition Research: Why and How. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 2018 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 30032218]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIoannidis JP. Implausible results in human nutrition research. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2013 Nov 14:347():f6698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6698. Epub 2013 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 24231028]

Dunbar SB, Khavjou OA, Bakas T, Hunt G, Kirch RA, Leib AR, Morrison RS, Poehler DC, Roger VL, Whitsel LP, American Heart Association. Projected Costs of Informal Caregiving for Cardiovascular Disease: 2015 to 2035: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 May 8:137(19):e558-e577. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000570. Epub 2018 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 29632217]

Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Beiser A, Levy D. Lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease. Lancet (London, England). 1999 Jan 9:353(9147):89-92 [PubMed PMID: 10023892]

Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011 May 19:473(7347):317-25. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21593864]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavies MJ, Woolf N, Rowles PM, Pepper J. Morphology of the endothelium over atherosclerotic plaques in human coronary arteries. British heart journal. 1988 Dec:60(6):459-64 [PubMed PMID: 3066389]

McGill HC Jr, McMahan CA, Zieske AW, Tracy RE, Malcom GT, Herderick EE, Strong JP. Association of Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors with microscopic qualities of coronary atherosclerosis in youth. Circulation. 2000 Jul 25:102(4):374-9 [PubMed PMID: 10908207]

Sata M, Saiura A, Kunisato A, Tojo A, Okada S, Tokuhisa T, Hirai H, Makuuchi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nature medicine. 2002 Apr:8(4):403-9 [PubMed PMID: 11927948]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995 Sep 1:92(5):1355-74 [PubMed PMID: 7648691]

Schoenhagen P, Ziada KM, Vince DG, Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM. Arterial remodeling and coronary artery disease: the concept of "dilated" versus "obstructive" coronary atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001 Aug:38(2):297-306 [PubMed PMID: 11499716]

Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Erikssen G, Jorgensen L, Cohn PF. Initial clinical presentation of cardiac disease in asymptomatic men with silent myocardial ischemia and angiographically documented coronary artery disease (the Oslo Ischemia Study). The American journal of cardiology. 1993 Sep 15:72(9):629-33 [PubMed PMID: 8249835]

Yew KS, Cheng E. Acute stroke diagnosis. American family physician. 2009 Jul 1:80(1):33-40 [PubMed PMID: 19621844]

Kreatsoulas C, Shannon HS, Giacomini M, Velianou JL, Anand SS. Reconstructing angina: cardiac symptoms are the same in women and men. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 May 13:173(9):829-31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.229. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23567974]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKirchberger I, Meisinger C, Heier M, Kling B, Wende R, Greschik C, von Scheidt W, Kuch B. Patient-reported symptoms in acute myocardial infarction: differences related to ST-segment elevation: the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry. Journal of internal medicine. 2011 Jul:270(1):58-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02365.x. Epub 2011 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 21338424]

Khafaji HA, Suwaidi JM. Atypical presentation of acute and chronic coronary artery disease in diabetics. World journal of cardiology. 2014 Aug 26:6(8):802-13. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i8.802. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25228959]

Robson J, Ayerbe L, Mathur R, Addo J, Wragg A. Clinical value of chest pain presentation and prodromes on the assessment of cardiovascular disease: a cohort study. BMJ open. 2015 Apr 15:5(4):e007251. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007251. Epub 2015 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 25877275]

Kannel WB, Abbott RD. Incidence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction. An update on the Framingham study. The New England journal of medicine. 1984 Nov 1:311(18):1144-7 [PubMed PMID: 6482932]

Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2005 Nov 23:294(20):2623-9 [PubMed PMID: 16304077]

Siket MS, Edlow J. Transient ischemic attack: an evidence-based update. Emergency medicine practice. 2013 Jan:15(1):1-26 [PubMed PMID: 23257070]

Hand PJ, Haisma JA, Kwan J, Lindley RI, Lamont B, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Interobserver agreement for the bedside clinical assessment of suspected stroke. Stroke. 2006 Mar:37(3):776-80 [PubMed PMID: 16484609]

Goldstein LB, Simel DL. Is this patient having a stroke? JAMA. 2005 May 18:293(19):2391-402 [PubMed PMID: 15900010]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSearls DE, Pazdera L, Korbel E, Vysata O, Caplan LR. Symptoms and signs of posterior circulation ischemia in the new England medical center posterior circulation registry. Archives of neurology. 2012 Mar:69(3):346-51. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2083. Epub 2011 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 22083796]

Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, Krook SH, Hunninghake DB, Comerota AJ, Walsh ME, McDermott MM, Hiatt WR. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001 Sep 19:286(11):1317-24 [PubMed PMID: 11560536]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSontheimer DL. Peripheral vascular disease: diagnosis and treatment. American family physician. 2006 Jun 1:73(11):1971-6 [PubMed PMID: 16770929]

Harris C, Croce B, Cao C. Thoracic aortic aneurysm. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2016 Jul:5(4):407. doi: 10.21037/acs.2016.07.05. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27563557]

Aggarwal S, Qamar A, Sharma V, Sharma A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review. Experimental and clinical cardiology. 2011 Spring:16(1):11-5 [PubMed PMID: 21523201]

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, Felner JM. An Overview of the Cardiovascular System. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250234]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBudoff MJ, Achenbach S, Blumenthal RS, Carr JJ, Goldin JG, Greenland P, Guerci AD, Lima JA, Rader DJ, Rubin GD, Shaw LJ, Wiegers SE, American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, American Heart Association Committee on Cardiac Imaging, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Assessment of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Committee on Cardiac Imaging, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2006 Oct 17:114(16):1761-91 [PubMed PMID: 17015792]

Kavousi M, Leening MJ, Nanchen D, Greenland P, Graham IM, Steyerberg EW, Ikram MA, Stricker BH, Hofman A, Franco OH. Comparison of application of the ACC/AHA guidelines, Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines, and European Society of Cardiology guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in a European cohort. JAMA. 2014 Apr 9:311(14):1416-23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2632. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24681960]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017 Aug 8:136(6):e137-e161. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28455343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarvalho-Pinto BP, Faria CD. Health, function and disability in stroke patients in the community. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2016 Jul-Aug:20(4):355-66. doi: 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0171. Epub 2016 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 27556392]

Bovim MR, Askim T, Lydersen S, Fjærtoft H, Indredavik B. Complications in the first week after stroke: a 10-year comparison. BMC neurology. 2016 Aug 11:16(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0654-8. Epub 2016 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 27515730]

Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, Browner D. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. The New England journal of medicine. 1992 Feb 6:326(6):381-6 [PubMed PMID: 1729621]

Aronow WS. Peripheral arterial disease of the lower extremities. Archives of medical science : AMS. 2012 May 9:8(2):375-88. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28568. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22662015]

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Authors/Task Force Members, Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European journal of heart failure. 2016 Aug:18(8):891-975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. Epub 2016 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 27207191]

Sandhoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. The Permanente journal. 2008 Summer:12(3):4-11 [PubMed PMID: 21331203]