Introduction

Blepharochalasis syndrome (BS) is an uncommon condition characterized by recurrent episodes of periocular edema in young patients. The first report of this syndrome was by the Austrian ophthalmologist Joseph Beer in 1807. However, Ernst Fuchs was the first to use the term "blepharochalasis" (from Greek "eyelid slackening") in 1896.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Several theories and triggering factors have been proposed concerning BS, but the ultimate etiology of this entity remains uncertain. Although the majority of cases are limited to the eyelid, there are reports of blepharochalasis associated with other systemic abnormalities. Some authors have, therefore, suggested that blepharochalasis might be part of a more complex systemic disorder.[3][4][5]

The different etiological theories that have been proposed include involvement of hormone influences, allergies, localized forms of cutis laxa, and idiopathic angioedema. However, most recent histopathological studies suggest that immunoglobulin (Ig) A deposits might play a role in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.[2][6][7]

Epidemiology

Accurate epidemiological data are not available due to the rarity of this syndrome. The available information is mainly based on case reports or small case series. BS usually has an onset in childhood or puberty. The episodes repeat every 3 to 4 months over a few years, becoming less frequent as the patient ages. Eventually, the inflammatory attacks cease, and the disease enters a quiescent stage. The largest review of blepharochalasis by Koursh et al. reported on 45 female and 22 male patients. The average age of onset was 11.4 years.[2]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of BS is controversial, and the ultimate mechanisms causing the disease have not been elucidated. The histopathological studies reported in a few cases recently provide new insights into the mechanisms behind this condition. The acute inflammatory episodes have been compared to localized angioedema in which an unknown trigger leads to a vascular impairment causing liquid extravasation and the swelling attack.

Repeated episodes of skin stretching would lead to the fragmentation, and eventually loss of the elastic fibers and tissue atrophy. However, the presence of Ig A deposits within the dermis and perivascular inflammatory cells infiltrates, described in several studies, suggest a possible immune reaction as an alternative. Moreover, Kaneoya et al. performed reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to analyze mRNA expression of elastin in the skin of a patient affected with BS. They found that the elastin mRNA expression was not different in the patient's cultured fibroblast comparing with healthy controls, suggesting that environmental factors or other matrix components of elastic fibers may be involved in the loss of elastic fibers. Blood tests, including cell counts, circulating Ig, C-reactive protein, C3, C4, and C1 - esterase inhibitor, have been reported as normal in these patients.[8][9][10]

Histopathology

Histopathological studies of skin biopsies have contributed to our understanding of blepharochalasis pathogenesis. The common finding in these specimens is the loss of elastic fibers of the dermis. The initial step is probably an IgA immune-mediated reaction directed against these fibers, as several recent studies have demonstrated IgA antibody deposits using immunofluorescence. Positive immunohistochemical staining for metalloproteinases MMP-3 and MMP-9 has also been reported in BS. This is also seen in other elastolytic diseases and suggests that these metalloproteinases may be involved in the pathogenesis of this condition. Other findings include atrophy affecting different structures of the dermis, increasing number and diameter of the skin capillaries, perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, and pigmentation in the papillary and upper reticular dermis.[2][6][8]

History and Physical

BS is characterized by recurrent episodes of, usually bilateral, upper lid swelling. As mentioned above, the attacks begin during childhood or puberty and repeat 3 - 4 times per year. Menstruation, fatigue, upper respiratory infection, lymphocytic leukemia, fever, physical or emotional trauma, bee sting, wind exposure, or exercise, have been proposed as possible trigger factors.

The acute stage lasts hours to days (average 2 days). During this phase, there is painless non-pitting edema. Skin erythema is also frequent. The patient may complain of a red eye and tearing. Repeated episodes of eyelid swelling lead to a very characteristic appearance of the eyelids and periocular area, with upper lid ptosis, wrinkled, discolored, and atrophic skin with dilated visible subcutaneous vessels. In the late stages of the disease, it is possible to see disinsertion of the ligamentous structures of the lateral canthus, causing a rounded lateral angle and even a shortening of the horizontal palpebral aperture (known as acquired blepharophimosis). As the levator aponeurosis dehiscence progresses, the upper lid ptosis becomes more evident, especially in the medial area, and the weakening of the orbital septum facilitates the prolapse of the orbital fat and lacrimal gland in some patients. There are also a few mentions of proptosis in unilateral cases, suggesting a possible orbital involvement.[2][11]

Collin attempted to classify this condition based on his observation of a series of 30 patients. He mentions an active/early phase, when the swelling episodes occur, and a quiescent/late stage when there are at least 2 years without attacks.[11]

Blepharochalasis might also present as part of systemic disease. In these cases, an examination of other anatomical areas is needed. The most frequent association is with the Ascher syndrome (blepharochalasis, double lip, and non-toxic thyroid enlargement), or acquired cutis laxa (redundant skin, skeletal anomalies, and multi organic impairment).[5][12]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of BS is based on the typical natural history and examination during the acute and quiescent stages. It is important to rule out other conditions by forming a comprehensive differential diagnosis. Although in some cases, blood tests and imaging might be performed, they are mostly to rule out other conditions, because the results of the complementary tests in BS are normal. Skin biopsy is usually not needed to make a diagnosis, although it may help by showing the typical loss of the dermis elastic fibers.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of BS should be aimed to reduce the swelling during the acute episodes and to correct the sequelae in the quiescent stage.

There are no well-defined protocols to treat inflammatory attacks. Several authors report good results with the use of steroids, both systemic and topical. However, there are only a few reports based on case series and suggest only some improvement. Considering the potential side effects of steroids, especially if administered systematically, this treatment is not accepted as a general rule for treating the BS, although it could be considered in certain cases. Other immunosuppressant agents have been tried topically, such as tacrolimus.[13]

Karakonji et al. reported improvement in the acute stage of two patients with BS using oral doxycycline, based on its properties as a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor.[14] Finally, oral acetazolamide has been reported in two case series with good outcomes. The rationale for using this diuretic is based upon the suggestion that BS is a localized eyelid form of angioedema.[15][16](B2)

Apart from these different attempts with discreet outcomes for treating the acute inflammatory attacks, the treatment of BS is mostly based on surgery to correct the complications. Surgery is reserved for patients in the quiescent phase after the disease has been quiet for 6 - 12 months. Otherwise, the risk of treatment failure increases significantly. As mentioned above, the most common sequelae in BS include dermatochalasis with either fat prolapse or fat atrophy, upper lid ptosis, lacrimal gland prolapse, and lateral canthus and lower eyelid malposition.

All these conditions need to be addressed with a wide armamentarium of surgical techniques that should be combined according to the case. Blepharoplasty, ptosis surgery, and canthal surgery in these patients are more challenging than in other cases, due to the particular changes seen in the periocular tissues of BS patients.[1][2][11][17][18] Tissue repositioning and fat grafting are used in addition to the reconstructive techniques aimed at tendons, the aponeurosis, and the lacrimal gland.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Different entities can resemble BS. In the acute phase, the differential diagnosis might be challenging, especially when inflammatory episodes begin, as all the various causes of acute and acute on chronic eyelid swelling must be considered:

- Allergic reactions

- Local eyelid infection/inflammation (stye, chalazion, etc.)

- Orbital inflammation

- Skin conditions

- Angioedema

- Melkerson-Rosenthal Syndrome

In the quiescent phase:

- Dermatochalasis

- Floppy eyelid syndrome

- Upper lid ptosis

- Acquired cutis laxa

- Eyelid/orbital masses

A comprehensive history and examination should be sufficient to differentiate BS from these conditions, especially when the swelling attacks recur.

Prognosis

The natural history of BS is well-established, although a wide variety of presentations in terms of the number of swelling attacks, and duration of the early stage, has been described. Depending on this, the number and severity of complications may be different in each patient. The impact of surgery on the possibility of recurrences is also unknown.[2]

Complications

BS is a non-sight-threatening disease, and its complications affect mainly the periocular anatomy. The recurrent episodes of eyelid swelling can lead to:

- Dermatochalasis with periocular fat atrophy in some cases, and fat prolapse in others

- Thin, wrinkled, atrophic, and discolored skin

- Upper lid ptosis, with normal levator function (suggesting ptosis secondary to aponeurotic dehiscence)

- Lateral (and occasionally medial) canthal disinsertion, with rounded deformity of the canthal angle and shortening of the horizontal palpebral fissure (acquired blepharophimosis)

- Pseudoepicanthal fold

- Lacrimal gland prolapse

- Lower lid laxity and malposition

- Secondary ocular surface irritation

Deterrence and Patient Education

BS is a rare disease with unknown etiology and no universally recognized curable treatment at present. However, it has no severe consequences for the patient's sight. It is important to know the disease to avoid a delay in making the diagnosis, which can result in patient anxiety. Once the diagnosis is made, it is important to inform the patients about the condition, the possible triggers, and some local measures that can be tried during the swelling episodes, such as the application of local cold. It is also important to warn patients about other diseases that can resemble BS and advise them to seek care when the swelling attacks occur, to confirm the diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

BS frequently poses a diagnostic dilemma because of the rarity of the condition, and the wide differential diagnosis. While the ophthalmologist is the main professional involved in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients, it is important to manage these cases with an interprofessional team. Other specialties, such as primary care, rheumatology, and dermatology, are important to rule out systemic associations of this syndrome. Radiologists may also help if neuroimaging is performed during the diagnostic evaluation, and pathologists are crucial if skin biopsy is done. Nurses are also an important member of the team, as they can help to assist with patient and family education about the disease.[2] [Level 5]

Media

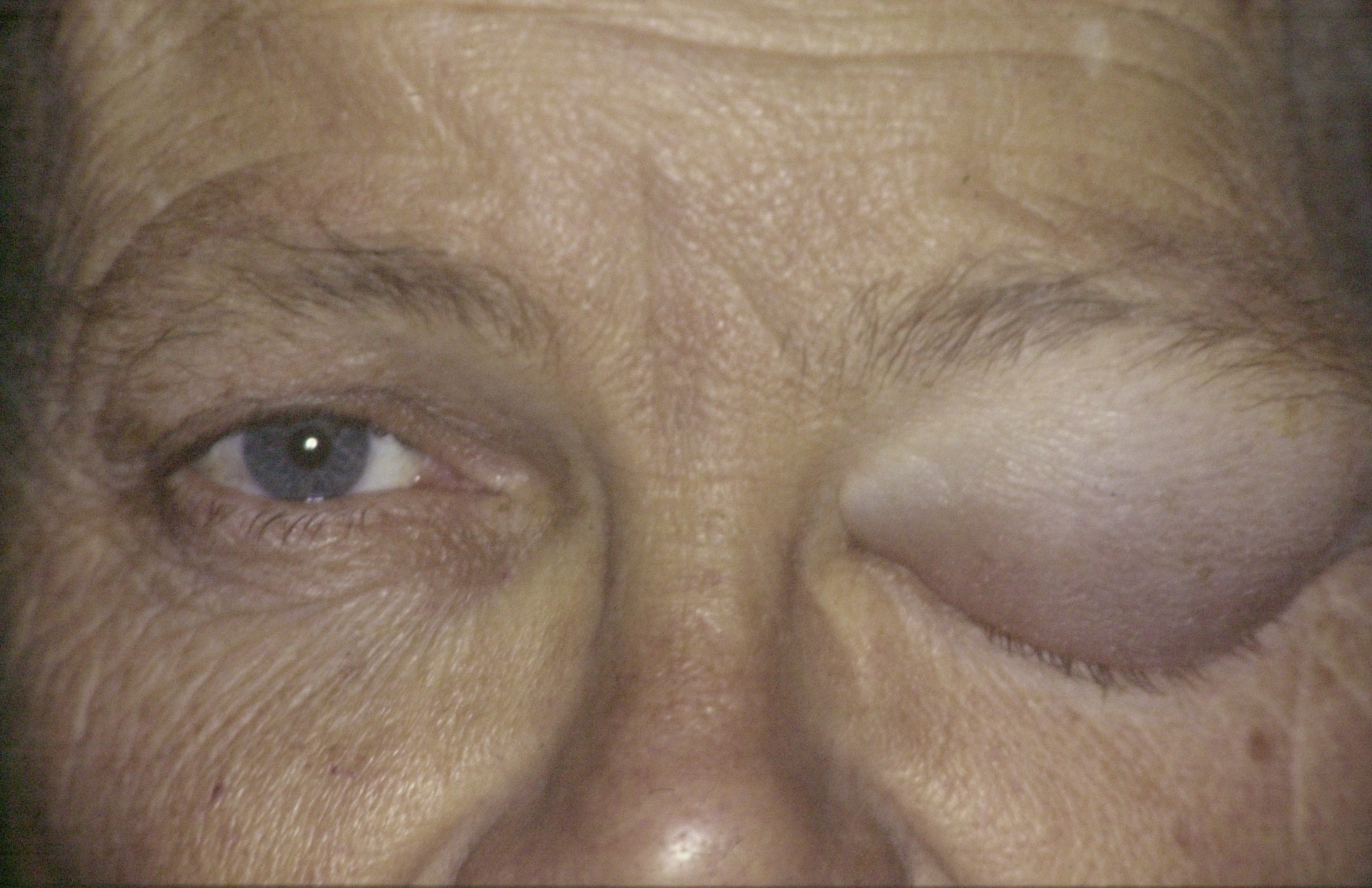

(Click Image to Enlarge)

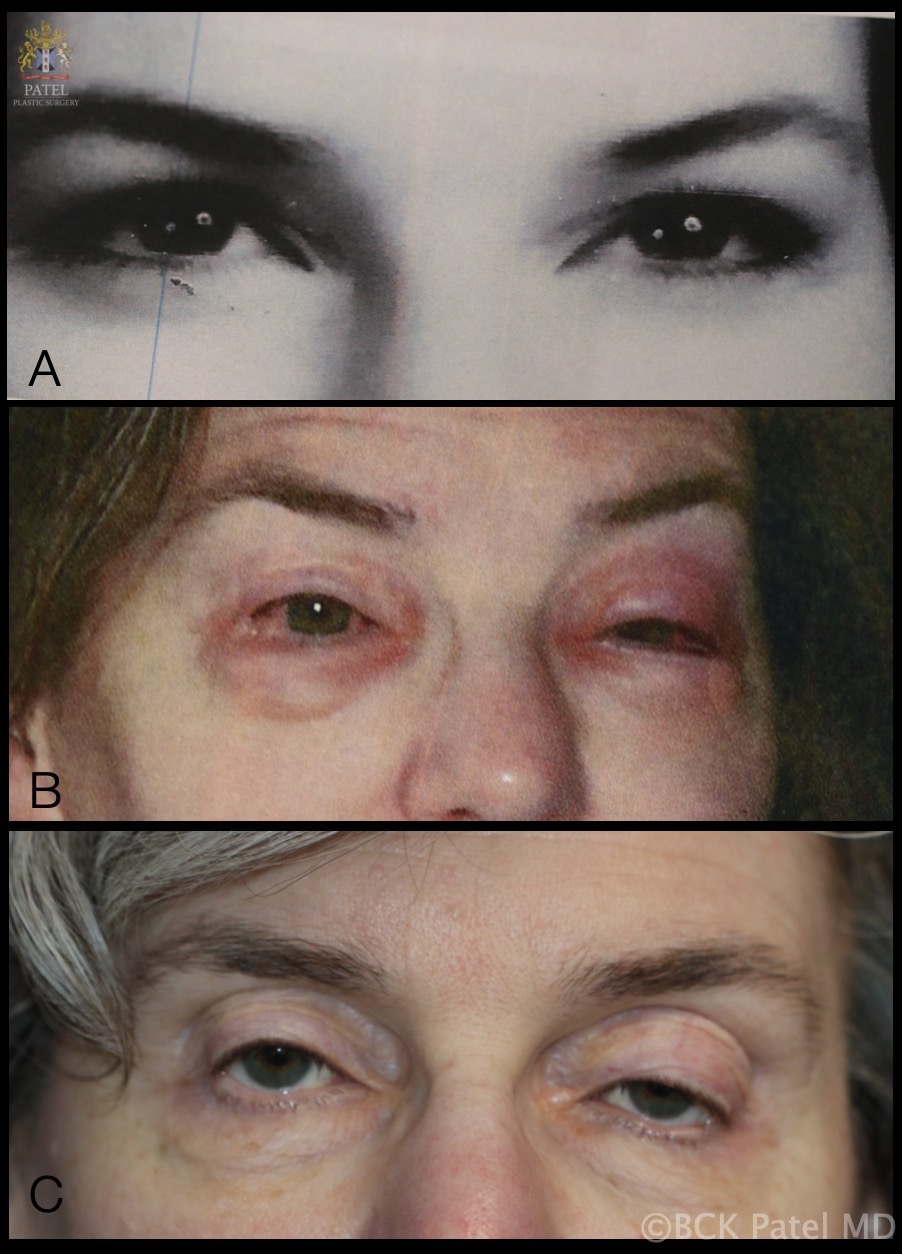

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Blepharochalasis: A 36-year-old female with her fifth episode of left-sided upper eyelid swelling. There is no pain or tenderness, no double vision and no limitation of ocular movements. The swelling settled in four days without any active treatment Contributed by Professor Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Blepharochalasis: A. Photograph that patient brought which was taken at the age of 18 years. B. One of multiple episodes of bilateral periorbital swelling which lasted "a few days each time". C. Appearance at age 54 years after having had attacks of blepharochalasis lasting a few days each time over several years. Patient now has periorbital tissue atrophy with levator disinsertion ptosis, loss of upper eyelid and brow fat and thinning of the eyelid skin Contributed by Professor Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Bergin DJ, McCord CD, Berger T, Friedberg H, Waterhouse W. Blepharochalasis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1988 Nov:72(11):863-7 [PubMed PMID: 3207663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoursh DM, Modjtahedi SP, Selva D, Leibovitch I. The blepharochalasis syndrome. Survey of ophthalmology. 2009 Mar-Apr:54(2):235-44. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19298902]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhose S, Kalra BR, Dayal Y. Blepharochalasis with multiple system involvement. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1984 Aug:68(8):529-32 [PubMed PMID: 6743619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrowning RJ, Sanchez AT, Mullins S, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Blepharochalasis: something to cry about. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2017 Mar:44(3):279-282. doi: 10.1111/cup.12841. Epub 2016 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 27718529]

Zhao ZL, Wang SM, Shao CY, Fu Y. Ascher syndrome: a rare case of blepharochalasis combined with double lip and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. International journal of ophthalmology. 2019:12(6):1044-1046. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2019.06.26. Epub 2019 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 31236366]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMotegi S, Uchiyama A, Yamada K, Ogino S, Takeuchi Y, Ishikawa O. Blepharochalasis: possibly associated with matrix metalloproteinases. The Journal of dermatology. 2014 Jun:41(6):536-8. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12503. Epub 2014 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 24815765]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaul M, Geller L, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Blepharochalasis: A rare cause of eye swelling. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2017 Nov:119(5):402-407. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.07.036. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29150067]

Grassegger A, Romani N, Fritsch P, Smolle J, Hintner H. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) deposits in lesional skin of a patient with blepharochalasis. The British journal of dermatology. 1996 Nov:135(5):791-5 [PubMed PMID: 8977684]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJordan DR. Blepharochalasis syndrome: a proposed pathophysiologic mechanism. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 1992 Feb:27(1):10-5 [PubMed PMID: 1555128]

Kaneoya K, Momota Y, Hatamochi A, Matsumoto F, Arima Y, Miyachi Y, Shinkai H, Utani A. Elastin gene expression in blepharochalasis. The Journal of dermatology. 2005 Jan:32(1):26-9 [PubMed PMID: 15841657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCollin JR. Blepharochalasis. A review of 30 cases. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1991:7(3):153-7 [PubMed PMID: 1911519]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDantas SG, Trope BM, de Magalhães TC, Azulay DR, Quintella DC, Ramos-E-Silva M. Blepharochalasis: A rare presentation of cutis laxa. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2019 May:110(4):327-329. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.04.006. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30722931]

Razmi T M, Takkar A, Chatterjee D, De D. Blepharochalasis: 'drooping eyelids that raised our eyebrows'. Postgraduate medical journal. 2018 Nov:94(1117):666-667. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-135706. Epub 2018 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 29936417]

Karaconji T, Skippen B, Di Girolamo N, Taylor SF, Francis IC, Coroneo MT. Doxycycline for treatment of blepharochalasis via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 May-Jun:28(3):e76-8. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31822ddf6e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21946773]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDrummond SR, Kemp EG. Successful medical treatment of blepharochalasis: a case series. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2009:28(5):313-6. doi: 10.3109/01676830903071190. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19874128]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLazaridou MN, Sandinha T, Kemp EG. Oral acetazolamide: A treatment option for blepharochalasis? Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2007 Sep:1(3):331-3 [PubMed PMID: 19668490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoka K, Patel BC. Ptosis Correction. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969650]

Hundal KS, Mearza AA, Joshi N. Lacrimal gland prolapse in blepharochalasis. Eye (London, England). 2004 Apr:18(4):429-30 [PubMed PMID: 15069442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence