Introduction

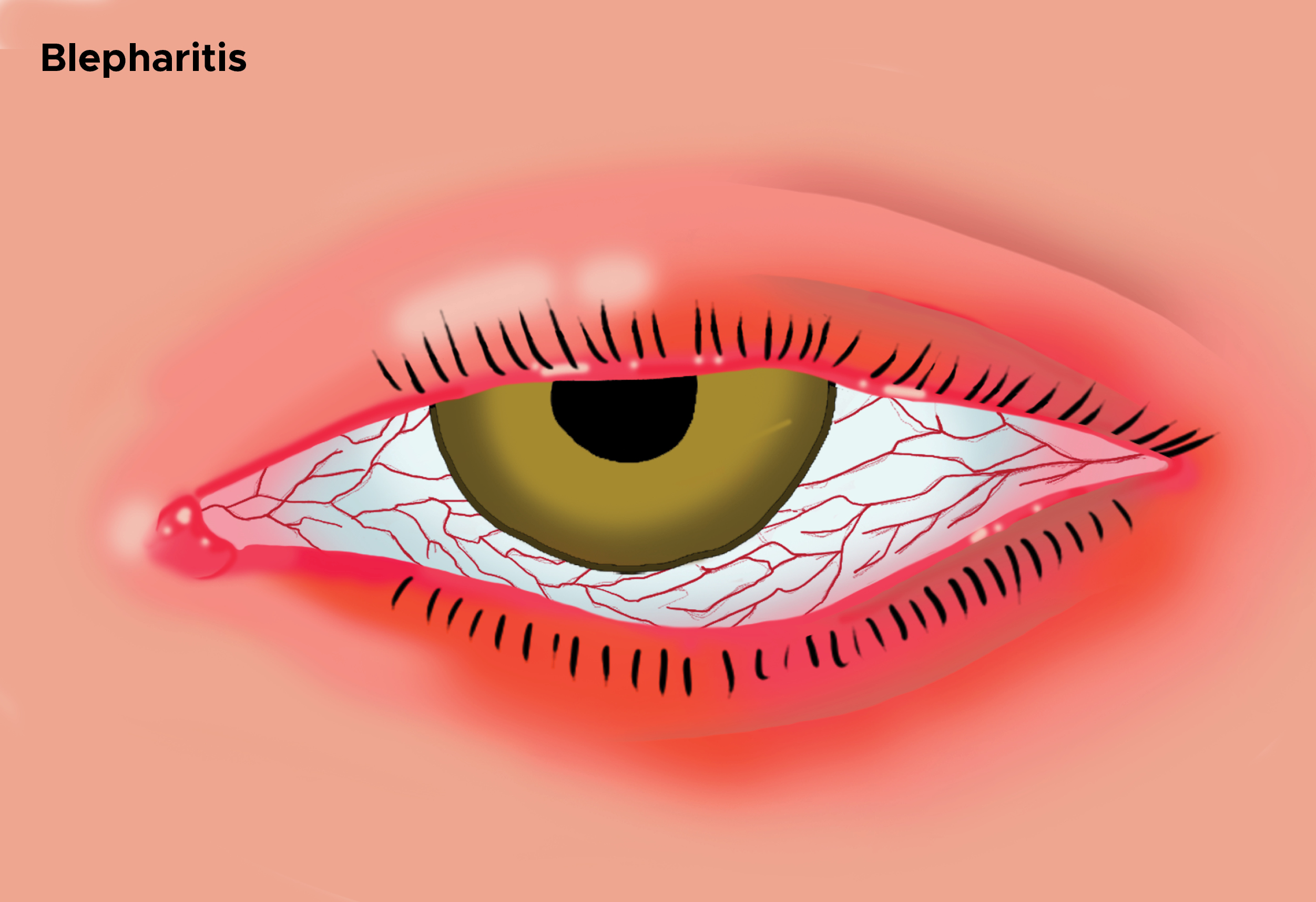

Blepharitis is an ophthalmologic condition characterized by an inflammation of the eyelid margins. It can be acute or chronic, with chronic being the more common form (see Image. Illustration of Blepharitis, Swollen Eye). It can further be defined by the location of the problem, anterior versus posterior. It usually presents with recurrent symptoms that may vary over time and involve both eyes. Blepharitis is a clinical diagnosis based on irritation of the lid margins with flaking and crusting of the lashes. The main treatment for blepharitis is good eyelid hygiene and elimination of triggers that exacerbate symptoms. Topical antibiotics may be prescribed. Patients refractory to these measures require referral to an ophthalmologist. The goal of treatment is to alleviate symptoms. Because most blepharitis is chronic, patients must maintain a good hygiene regimen to prevent recurrences. While there is no definitive cure, the prognosis for blepharitis is good. Blepharitis is a more symptomatic condition than a true health threat.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Causes of blepharitis differ depending on whether it is an acute or chronic process and, in the case of chronic, the location of the problem. Acute blepharitis may be ulcerative or nonulcerative. An infection causes ulcerative blepharitis. This is usually bacterial and, most commonly, staphylococcal. A viral etiology such as infection with Herpes simplex and Varicella zoster is also possible. Nonulcerative is usually an allergic reaction such as atopic or seasonal. Its location best classifies the chronic form of blepharitis. An infection, usually staphylococcal or seborrheic disease process, is involved in anterior blepharitis. Individuals frequently have seborrheic dermatitis of the face and scalp. Also, anterior blepharitis may be associated with rosacea. Meibomian gland dysfunction causes posterior blepharitis. The glands over-secrete an oily substance, becoming clogged and engorged. Commonly, this is associated with acne rosacea, and hormonal causes are suspected. Both anterior (Demodex folliculorum) and posterior (Demodex brevis) blepharitis may be caused by a Demodex mite. Their role is not well-established since asymptomatic individuals have also been found to harbor the mites at approximately the same prevalence.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

Blepharitis is not specific to any group of people. It affects people of all ages, ethnicities, and gender. It is more common in individuals older than the age of 50. The total number of cases in the US at any 1 time is unknown. In a 2009 US survey, 37% of patients seen by an ophthalmologist and 47% of patients seen by an optometrist had signs of blepharitis. A recent study carried out over 10 years (2004 through 2013) in South Korea determined the overall incidence to be 1.1 per 100 person-years. This increased with time and was higher in female patients. The overall prevalence for patients over 40 years of age was 8.8%.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of blepharitis is not known. The cause is most likely multifactorial. Causative factors include chronic low-grade bacterial infections of the ocular surface, inflammatory skin conditions such as atopy and seborrhea, and parasitic infestations with Demodex mites.

History and Physical

Patients with blepharitis typically describe itching, burning, and crusting of the eyelids. They may experience tearing, blurred vision, and foreign body sensations. In general, symptoms tend to worsen in the morning, with crusting of the lashes being most prominent upon waking. The symptoms tend to affect both eyes and can be intermittent. The physical exam is best performed using a slit lamp. In anterior blepharitis, slit lamp exam reveals erythema and edema of the eyelid margin. Telangiectasia may be present on the outer portion of the eyelid. Scaling can be seen at the base of the eyelashes, forming "collarettes." Also, loss of lashes (madarosis), depigmentation of lashes (poliosis), and misdirection of lashes (trichiasis) may be seen. In posterior blepharitis, the meibomian glands are dilated, obstructed, and may be capped with oil. Secretions from these glands may appear thick, and lid scarring may be present in the area around the glands. The tear film may show signs of rapid evaporation in all types of blepharitis. This is best evaluated by measuring the tear break-up time. A slit lamp exam is performed, and fluorescein dye is placed in the eye. The patient is asked to blink fully and maintain an open eye for 10 seconds. The tear film is examined for breaks or dry spots under cobalt blue light. Generally, a tear break-up time of less than 10 seconds is considered abnormal.

Evaluation

Blepharitis is a clinical diagnosis. No specific diagnostic testing beyond the history and physical exam is required. Individuals who fail treatment for chronic blepharitis should undergo a lid biopsy to exclude carcinoma, especially in cases of eyelash loss.

Treatment / Management

Eyelid hygiene remains the mainstay of treatment and is effective in treating most cases of blepharitis. Warm, wet compresses are applied to the eye for 5 to 10 minutes to soften eyelid debris and oils and dilate meibomian glands. Immediately following this, the eyelid margins should be washed gently with a cotton applicator soaked in diluted baby shampoo to remove scale and debris. Care should be taken not to use too much soap since it can result in dry eyes. Individuals with posterior blepharitis benefit from a gentle massage of the eyelid margins to express oils from the meibomian glands. A cotton applicator or finger massage the lid margins in small circular patterns. During symptomatic blepharitis exacerbations, eyelid hygiene must be performed 2 to 4 times daily. In patients with chronic blepharitis, a lid-hygiene regimen needs to be maintained daily for life, or irritating symptoms recur. In addition, eye makeup needs to be limited and all triggers removed. Underlying conditions should be treated.[8][9][10][11]

Topical antibiotics should be used in all acute and anterior blepharitis cases. They are useful in symptomatic relief and eradicating bacteria from the lid margin. Topical antibiotic creams like bacitracin or erythromycin can be applied to the lid margin for 2 to 8 weeks. Oral tetracyclines and macrolide antibiotics may be used to treat posterior blepharitis that is not responsive to eyelid hygiene or is associated with rosacea. These oral antibiotics are used for their anti-inflammatory and lipid-regulating properties. Short courses of topical steroids are beneficial in patients with ocular inflammation. Recent trials have shown that antibiotics and corticosteroids can significantly improve symptoms. These often are prescribed as a combination topical treatment in patients who have failed eyelid hygiene treatment. In patients who are felt to have significant Demodex infestations, tea tree oil eyelid, and shampoo scrubs can be beneficial for a minimum of 6 weeks.

Recent new therapies have become available for the treatment of blepharitis. Thermal pulsation therapy (LipiFlow device) applies heat to anterior and posterior surfaces. Pulsations gently remove debris and crustings from the meibomian glands. MiBoFlo is a thermal therapy that is applied to the eyelids outside. BlephEx is a rotating light burr used to remove debris from meibomian gland orifices. This allows a better flow of oils and an improved response to heat therapies. The Maskin probe is a stainless steel probe applied to an anesthetized meibomian gland orifice. A light electrical current is applied to the gland to facilitate oil secretion. While some small trials have shown promise, further clinical trials are needed to establish the efficacy of these treatments.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for blepharitis include the following:

- Bacterial conjunctivitis

- Bacterial keratitis

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Chalazion

- Contact lens complications

- Dry eye disease

- Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis

- Hordeolum

- Ocular rosacea

- Trichiasis

Pearls and Other Issues

While rarely sight-threatening, blepharitis can result in eyelid scarring, excessive tearing, hordeolum and chalazion formation, and chronic conjunctivitis. The development of keratitis and corneal ulcers can result in vision loss. Blepharitis is a chronic condition characterized by exacerbations and remissions. While symptoms may be improved, there is rarely a cure.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Blepharitis is managed by an interprofessional team that consists of a nurse practitioner, primary care provider, ophthalmologist, and internist. Blepharitis is characterized by an inflammation of the eyelid margins, which can be acute or chronic. The main treatment for blepharitis is good eyelid hygiene and elimination of triggers that exacerbate symptoms. Topical antibiotics may be prescribed. Patients refractory to these measures require referral to an ophthalmologist. The goal of treatment is to alleviate symptoms. Because most blepharitis is chronic, patients must maintain a good hygiene regimen to prevent recurrences. While there is no definitive cure, the prognosis for blepharitis is good. Blepharitis is a more symptomatic condition than a true health threat. Most patients do respond to treatment, but exacerbations and remissions characterize the condition.[12]

Media

References

Huggins AB, Carrasco JR, Eagle RC Jr. MEN 2B masquerading as chronic blepharitis and euryblepharon. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Dec:38(6):514-518. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2019.1567800. Epub 2019 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 30688132]

Rodriguez-Garcia A, Loya-Garcia D, Hernandez-Quintela E, Navas A. Risk factors for ocular surface damage in Mexican patients with dry eye disease: a population-based study. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():53-62. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S190803. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30613133]

Choi FD, Juhasz MLW, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Topical ketoconazole: a systematic review of current dermatological applications and future developments. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2019 Dec:30(8):760-771. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1573309. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30668185]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOzkan J, Willcox MD. The Ocular Microbiome: Molecular Characterisation of a Unique and Low Microbial Environment. Current eye research. 2019 Jul:44(7):685-694. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2019.1570526. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30640553]

Khoo P, Ooi KG, Watson S. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions for meibomian gland dysfunction: An evidence-based review of clinical trials. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2019 Jul:47(5):658-668. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13460. Epub 2019 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 30561146]

Soh Qin R, Tong Hak Tien L. Healthcare delivery in meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis. The ocular surface. 2019 Apr:17(2):176-178. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.11.007. Epub 2018 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30458245]

Fromstein SR, Harthan JS, Patel J, Opitz DL. Demodex blepharitis: clinical perspectives. Clinical optometry. 2018:10():57-63. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S142708. Epub 2018 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 30214343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePflugfelder SC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. The ocular surface. 2014 Oct:12(4):273-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.05.005. Epub 2014 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 25284773]

Kanda Y, Kayama T, Okamoto S, Hashimoto M, Ishida C, Yanai T, Fukumoto M, Kunihiro E. Post-marketing surveillance of levofloxacin 0.5% ophthalmic solution for external ocular infections. Drugs in R&D. 2012 Dec 1:12(4):177-85. doi: 10.2165/11636020-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23075336]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 1345157]

Veldman P, Colby K. Current evidence for topical azithromycin 1% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of blepharitis and blepharitis-associated ocular dryness. International ophthalmology clinics. 2011 Fall:51(4):43-52. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31822d6af1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21897139]

Hosseini K, Bourque LB, Hays RD. Development and evaluation of a measure of patient-reported symptoms of Blepharitis. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2018 Jan 11:16(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0839-5. Epub 2018 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 29325546]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence