Introduction

Biliary colic is a common presentation of a stone in the cystic duct or common bile duct of the biliary tree. Colic refers to the type of pain that "comes and goes," typically after eating a large, fatty meal which causes contraction of the gallbladder. However, the pain is usually constant and not colicky. Treatment of this disease is primarily surgical, involving removal of the gallbladder, typically using a laparoscopic technique. This medical condition does not typically require hospital admission.[1][2] Biliary colic generally refers to the pain that occurs from a temporary obstruction of the biliary tree which resolves on its own. Prolonged obstruction of the biliary tree or complete impaction of a stone within the biliary tree will eventually lead to cholecystitis or cholangitis, at which pain the pain will constant and increasing.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Gallstones are formed within the gallbladder and may be composed of either cholesterol or bilirubin. These stones may stay in the gallbladder and remain asymptomatic or may enter the cystic duct or common bile duct where they may become lodged and cause pain when the gallbladder contracts. The pain typically arises after fatty meals, when the gallbladder contracts to release bile into the duodenum to aid in digestion by emulsifying fats. Stones commonly exist within the gallbladder without symptoms, referred to as asymptomatic cholelithiasis. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis typically requires no medical or surgical treatment and may be managed expectantly and does not require further follow up. However, if pain, nausea, or vomiting do present, most commonly as right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain, the patient may be diagnosed with symptomatic cholelithiasis and will require surgical evaluation.[3][4] If the pain resolves on its own, typically by the stone either passing through the common bile duct and into the duodenum or by falling back into the gallbladder after obstructing the cystic duct, then it is termed biliary colic.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that somewhere between 10% to 20% of adults have gallstones, of which 1% to 3% of patients are symptomatic. In the United States, approximately 500,000 people require cholecystectomy due to all types of biliary disease. Biliary colic has a female predominance due to the influence of estrogen on the formation of gallstones. Obesity and elevated cholesterol are also strongly correlated to biliary colic and gallbladder disease because in the United States most gallstones are cholesterol-based.[5][6] In the developing world, the so-called pigmented stones derived from bilirubin are more common and are associated with hematologic disorders as well as biliary tree infections. Any type of stone may cause biliary colic, potentially progressing to cholecystitis or cholangitis, if it obstructs the cystic duct or the common bile duct.

Pathophysiology

Gallstones are formed in the gallbladder and can be composed of cholesterol or bilirubin. Fatty meals cause the release of cholecystokinin (CCK) from the duodenum, which subsequently causes contraction of the gallbladder. This contraction can expel stones from the gallbladder into the cystic duct or common bile duct. Less commonly, stones may also be formed within the common bile duct (CBD) and are referred to as primary CBD stones. These stones irritate the lining of the ducts, causing pain, which notably is present during times of gallbladder and duct contraction.[7][8] The stones may also become impacted in the cystic duct or common bile duct, with pain resulting when the gallbladder contracts against the obstruction.

History and Physical

Patients typically present with postprandial pain that "comes and goes," hence the term colic. The pain is usually in the RUQ of the abdomen and may have radiation into the back. With uncomplicated biliary colic, patients will likely present only with pain. However, some may also report nausea and/or vomiting. These symptoms are accentuated after meals.

Biliary colic patients are afebrile and will commonly have no abnormal vitals in contrast to acute cholecystitis or cholangitis, which may present with fevers, tachycardia, or even hypotension if they progress to septic shock.

Patients with biliary colic will generally only have right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric tenderness on physical exam. Abdominal distension and rebound tenderness are less common. Jaundice is not seen with blockage of the cystic duct; however, it is common with blockage of the common bile duct due to an elevation of direct bilirubin. This finding would suggest a more serious obstruction of the biliary tree and should raise suspicion for potential cholangitis rather than biliary colic.

Risk factors to ascertain for biliary colic:

- Elderly patient

- Pregnancy

- North European descent

- Recent weight loss

- Obesity

- Liver transplant

Evaluation

Laboratory tests to be ordered include a complete blood count (CBC) and a metabolic panel with liver function tests. It is important to have these tests to rule out more serious gallbladder pathology such as acute cholecystitis or cholangitis. With an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, the suspicion of acute cholecystitis or cholangitis rises. Elevated liver enzymes such as direct bilirubin, AST, ALT, ALP, and GGT suggest a stone or blockage in the common bile duct. Stones within the gallbladder or cystic duct typically do not produce any laboratory abnormalities unless it has progressed from biliary colic to cholecystitis in which case leukocytosis may be seen.[2][9]

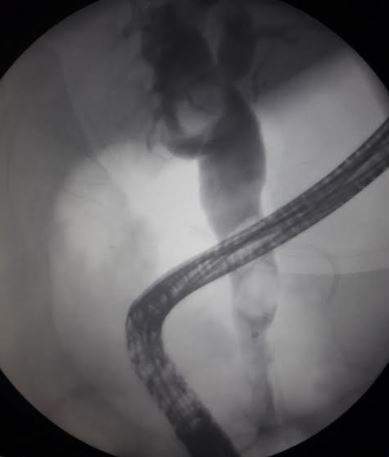

RUQ abdominal ultrasound is the first radiologic test to evaluate suspected biliary pathology. HIDA scans are useful in evaluating acute or chronic cholecystitis and biliary dyskinesia. Abdominal CT is less sensitive than ultrasound at evaluating stones within the gallbladder. However, CT scans are a common modality used by emergency room physicians for nonspecific severe abdominal pain, which may find gallstones present. MRCP may be used for better visualization of the biliary tree, especially when evaluating for choledocholithiasis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can be used to evaluate for common bile duct stones if all other imaging is equivocal. ERCP is also a therapeutic intervention for choledocholithiasis.

Classic findings on RUQ ultrasound for biliary colic include stones (size may vary) or stone shadow. Findings of pericholecystic fluid, thickened wall (greater than 0.4 cm), and distended gallbladder are more indicative of acute cholecystitis.

Treatment / Management

Management of biliary colic is primarily surgical. Medical management of biliary colic involves strict maintenance of a low-fat diet and supportive management with antiemetics and pain control, however since patients typically have multiple stones the risk for recurrence of their biliary colic is high. There is no role for antibiotics in biliary colic as there is no infectious etiology, such as in acute cholecystitis or cholangitis. Oral ursodeoxycholic acid has also been used to help dissolve gallstones. Surgical intervention with laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains the gold standard. In patients who are poor surgical candidates, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy may be considered, but there is a considerable chance of stone recurrence. Open cholecystectomy is a less common approach, used in patients who are not candidates for laparoscopic surgery.[10][11](B2)

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is both diagnostic and therapeutic for common bile duct stones. Sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater can assist in removing stones after ERCP and prevent future stones from becoming lodged in the common bile duct.

Patients with biliary colic do not necessarily require hospital admission. They may be treated symptomatically with a low-fat diet, pain control, and anti-emetics, and follow up for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy as an outpatient within a reasonable time-frame. However, if the patient has severe or intractable abdominal pain, hospital admission, and more urgent surgical management are warranted for symptomatic relief. Other considerations for possible admission include large gallstones. Stones greater than 1 cm in size have a greater propensity to obstruct the cystic duct and may predispose to acute cholecystitis, so they should be treated with surgical management more urgently. If the patient is unable to tolerate anything by mouth (even liquid), admission should be considered.

Differential Diagnosis

- Hepatitis

- Cholangitis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Pancreatitis

- Renal calculi

- Viral or bacterial gastroenteritis

- Biliary dyskinesia

Complications

- Pancreatitis

- Cholangitis

- Gallbladder perforation

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Cholecystectomy for biliary colic is an elective procedure and thus has a very favorable postoperative course. Since biliary colic by definition precedes the more serious inflammation that accompanies cholecystitis the dissection and removal of the gallbladder is typically much easier. Patients can often be discharged the same day or after a single day in the hospital provided they can tolerate appropriate oral intake of hydration and nutrition and their pain is well controlled.

Consultations

Biliary colic can be handled by a general surgery service without consultation of other services. However, if there is a concern for potential gallstones in the common bile duct then gastroenterology may be contacted for possible ERCP.

Deterrence and Patient Education

If a patient with biliary colic chooses nonoperative management of their condition then it is imperative to educate them on the warning signs of cholecystitis. They should be told to present to the hospital promptly if their abdominal pain persists longer than a few hours, becomes much greater than usual, or if they develop an accompanying fever. These patients should be made aware they are at high risk for developing an impacted stone which can lead to dangerous infectious processes such as cholecystitis or cholangitis. They should also be educated that fatty meals cause gallbladder contraction and can precipitate their symptoms.

Pearls and Other Issues

Aside from symptomatic cholelithiasis, complications of gallstones include acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis depending on the location of the stone in the biliary tree. These diseases are more serious and do require hospital admission and medical management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with biliary colic often present to the emergency department with vague complaints. Besides blood work, imaging studies are necessary. The diagnosis and management of this disorder require an interprofessional team, including emergency department personnel, gastroenterologists, specialty care nurses, and dieticians. While the treatment of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis is established, there is also some evidence indicating that the condition can be prevented by changing diet and lifestyle. Anecdotal reports indicate that lowering the amount of fat in the diet may reduce biliary colic. Reducing body weight gradually has also been shown to lower the risk of biliary colic- hence the patient should be educated on the importance of a low-fat diet and regular exercise. These patients should be educated on the signs and symptoms of acute cholecystitis and when to seek medical help. For patients treated with surgery, the majority have an excellent outcome.[12][13] [Level 5]

Media

References

Baiu I, Hawn MT. Gallstones and Biliary Colic. JAMA. 2018 Oct 16:320(15):1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11868. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30326127]

Naim H, Hasan SA, Khalid S, Abbass A, DSouza J. Clinical Cholecystitis in the Absence of the Gallbladder. Cureus. 2017 Nov 10:9(11):e1834. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1834. Epub 2017 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 29340256]

Saurabh S, Green B. Is hyperkinetic gallbladder an indication for cholecystectomy? Surgical endoscopy. 2019 May:33(5):1613-1617. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6435-2. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30209609]

Wilkins T, Agabin E, Varghese J, Talukder A. Gallbladder Dysfunction: Cholecystitis, Choledocholithiasis, Cholangitis, and Biliary Dyskinesia. Primary care. 2017 Dec:44(4):575-597. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.002. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 29132521]

Hedström J, Nilsson J, Andersson R, Andersson B. Changing management of gallstone-related disease in pregnancy - a retrospective cohort analysis. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Sep:52(9):1016-1021. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1333627. Epub 2017 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 28599581]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCervellin G, Mora R, Ticinesi A, Meschi T, Comelli I, Catena F, Lippi G. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute abdominal pain in a large urban Emergency Department: retrospective analysis of 5,340 cases. Annals of translational medicine. 2016 Oct:4(19):362 [PubMed PMID: 27826565]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsai TJ, Chan HH, Lai KH, Shih CA, Kao SS, Sun WC, Wang EM, Tsai WL, Lin KH, Yu HC, Chen WC, Wang HM, Tsay FW, Lin HS, Cheng JS, Hsu PI. Gallbladder function predicts subsequent biliary complications in patients with common bile duct stones after endoscopic treatment? BMC gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 27:18(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0762-6. Epub 2018 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 29486713]

Wybourn CA, Kitsis RM, Baker TA, Degner B, Sarker S, Luchette FA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia: Which patients have long term benefit? Surgery. 2013 Oct:154(4):761-7; discussion 767-8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.044. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24074413]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeğerli V, Korkmaz T, Mollamehmetoğlu H, Ertan C. The importance of routine bedside biliary ultrasonography in the management of patients admitted to the emergency department with isolated acute epigastric pain. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2017 Aug 23:47(4):1137-1143. doi: 10.3906/sag-1603-12. Epub 2017 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 29156853]

Demehri FR, Alam HB. Evidence-Based Management of Common Gallstone-Related Emergencies. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2016 Jan:31(1):3-13. doi: 10.1177/0885066614554192. Epub 2014 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 25320159]

Bani Hani MN. Laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic cholelithiasis during pregnancy. Surgical laparoscopy, endoscopy & percutaneous techniques. 2007 Dec:17(6):482-6 [PubMed PMID: 18097304]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAltieri MS, Yang J, Zhu C, Sbayi S, Spaniolas K, Talamini M, Pryor A. What happens to biliary colic patients in New York State? 10-year follow-up from emergency department visits. Surgical endoscopy. 2018 Apr:32(4):2058-2066. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5902-5. Epub 2017 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 29063306]

Santucci NR, Hyman PE, Harmon CM, Schiavo JH, Hussain SZ. Biliary Dyskinesia in Children: A Systematic Review. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2017 Feb:64(2):186-193. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001357. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27472474]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence