Introduction

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatological condition predominantly associated with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. First described in 1996, necrolytic acral erythema is characterized by painful, erythematous, eroded, and occasionally bullous plaques primarily affecting the acral areas, such as the hands and feet.[1] Although not fully understood, the pathogenesis of this condition is believed to involve complex interactions between nutritional deficiencies, particularly zinc, and chronic liver disease. Necrolytic acral erythema is a crucial cutaneous marker for HCV infection, often presenting in patients with long-standing, untreated, or poorly managed HCV. The lesions are typically well-demarcated, erythematous, eroded plaques with superficial necrosis and crusting.[2] Necrolytic acral erythema typically follows a chronic course with recurrent episodes of exacerbation and remission.

Diagnosis involves a comprehensive evaluation to uncover underlying causes and metabolic abnormalities, emphasizing testing for HCV. Histological analysis may be required to differentiate necrolytic acral erythema from other similar skin conditions. Without appropriate management, the condition can persist and lead to significant discomfort and secondary infections due to impaired skin barrier.[3] Treatment focuses on addressing the HCV infection and the skin lesions, with oral zinc therapy showing significant effectiveness. Despite its apparent association with HCV, necrolytic acral erythema remains poorly understood and underreported, making its prevalence and incidence challenging to determine.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Necrolytic acral erythema is primarily associated with HCV infection, which is central to its pathogenesis. The exact mechanism by which HCV leads to necrolytic acral erythema is not fully elucidated but involves several key factors. The virus may induce skin changes through direct viral effects, immune-mediated mechanisms, or metabolic disturbances related to liver dysfunction.[4]

Epidemiology

Necrolytic acral erythema was initially reported among patients in areas with highly prevalent and untreated HCV infection, such as Egypt. Subsequent studies have reported cases from various regions worldwide, including the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and North America. However, the prevalence and incidence of necrolytic acral erythema remain poorly defined due to its rarity and underreporting in clinical practice.[5] Although initially considered a rare dermatosis, its association with chronic HCV infection has led to increased recognition in regions with a high prevalence of HCV. Necrolytic acral erythema predominantly affects adults, with the majority of reported cases occurring in individuals between the ages of 40 and 60, and does not appear to have a gender predilection.[6] Chronic HCV infection is considered the primary associated factor in the pathogenesis of necrolytic acral erythema. Infection is common in patients with necrolytic acral erythema; however, viral loads are not necessarily elevated.[7]

Pathophysiology

Zinc deficiency is a well-recognized factor in the development of necrolytic acral erythema.[7] Zinc is an essential cofactor in numerous enzymatic processes, including skin integrity and repair.[8] Experts have also hypothesized that HCV infection exacerbates zinc deficiency by altering zinc metabolism or through the systemic inflammatory response it provokes. In addition, the infection can lead to liver dysfunction, affecting metabolic processes and nutritional status.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica, a condition caused by zinc deficiency, provides a pertinent example of this pathophysiology. This autosomal recessive disorder is characterized by mutations in SLC39A4, which encodes a zinc transporter protein essential for zinc uptake in the intestine. The resulting impaired zinc absorption manifests as acral and periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. Both necrolytic acral erythema and acrodermatitis enteropathica highlight zinc's critical role in maintaining skin health and the systemic consequences of its deficiency. Understanding the pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in necrolytic acral erythema, including its impact on enzymatic processes and skin integrity, underscores the importance of addressing zinc levels in affected patients.[9] In addition, malabsorption of essential nutrients, including amino acids and vitamins, can contribute to skin manifestations. The resultant hypoaminoacidemia may impair protein synthesis and skin barrier function, exacerbating the symptoms of necrolytic acral erythema.[10]

Histopathology

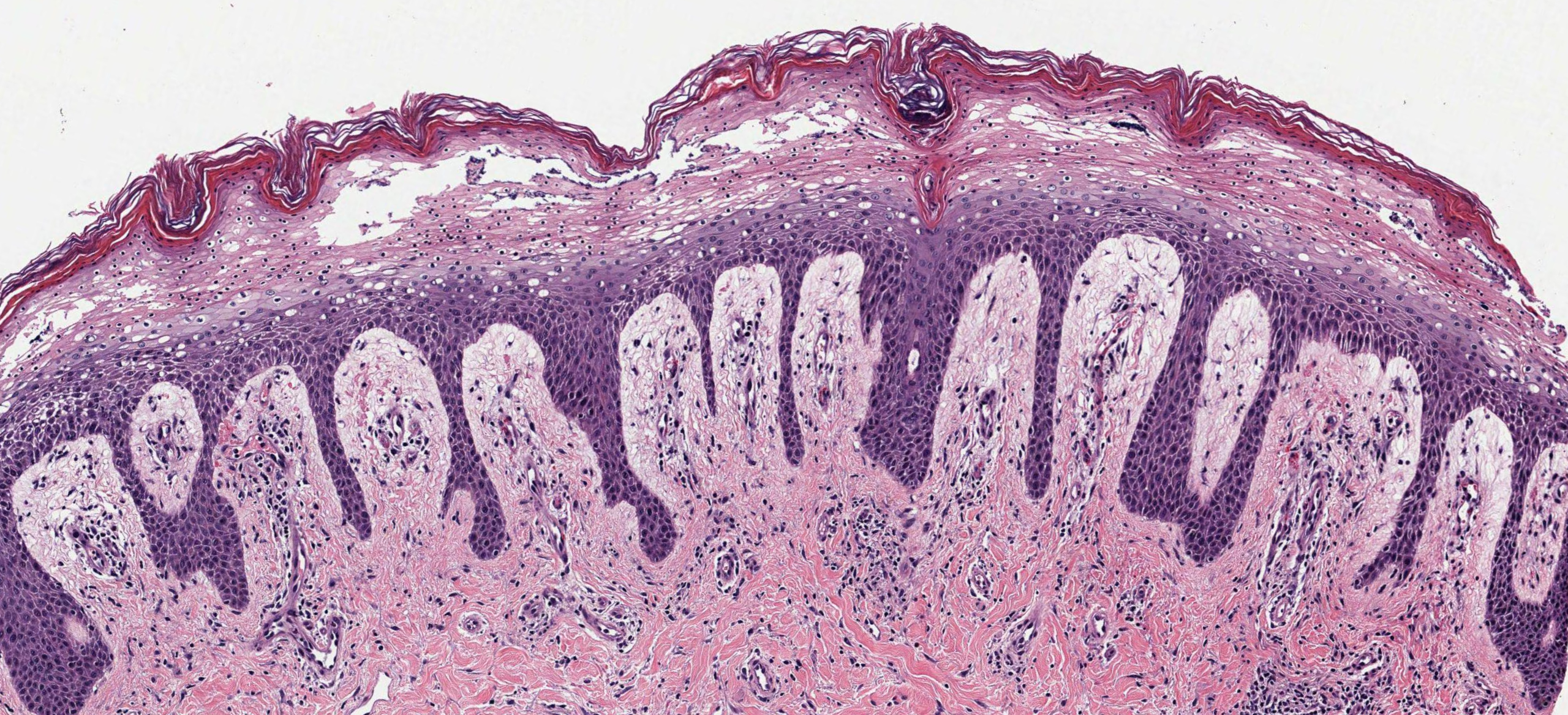

The histology of necrolytic acral erythema depends on the disease's location and stage at the time of biopsy. In the early stages, the outer layer of the epidermis exhibits necrosis, leading to blister formation as the epidermis detaches from the underlying tissue. Histologically, the epidermis shows thickening (acanthosis) and intercellular edema (spongiosis), accompanied by superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate resembling nummular dermatitis. The accumulation of necrotic keratinocytes can lead to the formation of clefts in the upper epidermis (see Image. Necrolytic Acral Erythema Histopathology). In addition, areas of dyskeratosis (abnormal keratinization) and epidermal pallor help differentiate necrolytic acral erythema from psoriasis. The characteristic necrosis of keratinocytes and vacuolar degeneration of some basal cells are critical diagnostic features of necrolytic acral erythema.[11]

History and Physical

Patients with necrolytic acral erythema may be unaware of their HCV status. Moreover, given the different stages and durations of necrolytic acral erythema, history may be variable, with lesions presenting intermittently.[6] Necrolytic acral erythema is characterized by painful, erythematous, eroded, and occasionally bullous plaques primarily affecting the acral areas, such as the hands and feet.[1]

Physical examination findings may show lesions in 3 distinct stages—initial, well-developed, and late. The initial stage presents with lesions that begin as small, erythematous macules or plaques that gradually enlarge and develop central necrosis and crusting. In the well-developed stages, the lesions merge to form distinct, thick, dark plaques with attached scales. As the condition progresses to the late stage, the lesions become more circumscribed, thinner, and hyperpigmented.[1]

Evaluation

The evaluation of necrolytic acral erythema involves a thorough investigation to identify underlying causes and metabolic disturbances. Early recognition of necrolytic acral erythema is crucial for diagnosing and treating any underlying conditions, particularly HCV infection. In more than 75% of necrolytic acral erythema cases, HCV is diagnosed for the first time, highlighting the importance of HCV serology in all patients with necrolytic acral erythema.[1]

Although no specific diagnostic laboratory tests exist for necrolytic acral erythema, a comprehensive biochemical evaluation is essential. Serum zinc levels are typically normal, though isolated reports indicate occasional low levels.[12][13] In addition, measuring amino acid and albumin levels is important, as these may be abnormal in some patients. Normal glucagon levels can help to differentiate necrolytic acral erythema from necrolytic migratory erythema. Liver function tests, including transaminase levels and total serum bilirubin, are crucial, particularly for HCV patients. Abnormal liver function tests and ultrasonography findings are common, reported in 84.3% and 76.9% of cases, respectively.[6] Furthermore, investigations should be conducted to rule out other differential diagnoses based on the clinical presentation of necrolytic acral erythema. This diagnostic approach results in more accurate identification and appropriate management of the condition.

Treatment / Management

The management of necrolytic acral erythema focuses on treating both the underlying cause and the skin manifestations. In patients with HCV infection, antiviral treatments such as ribavirin and interferon-alpha have been shown to improve the condition, even if the viral load remains high. Interferon-alpha monotherapy has also been effective. Oral zinc therapy is recognized as the most effective treatment for necrolytic acral erythema, even in patients without a deficiency. Interestingly, zinc therapy has also been noted to enhance the efficacy of interferon treatment in HCV patients with necrolytic acral erythema. A 220 mg oral zinc regimen taken twice daily for up to 8 weeks has been shown to clear skin findings.[14] Other treatments have been explored with varied results. Mid- to high-potency topical and systemic corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus have been tried with mixed results.[15] Phototherapy methods, including psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy, have also been tested but have not shown benefit.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

Necrolytic acral erythema can be misdiagnosed as several other dermatological conditions with similar clinical features, including erythema, scaling, and psoriasiform plaques. Accurate differentiation is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Conditions presenting with acral erythemas include acrodermatitis enteropathica, the dermatitis of niacin deficiency, and deficiencies such as biotin and fatty acid. These conditions typically have a distinctive acral distribution and lack systemic symptoms, which helps distinguish them from necrolytic acral erythema.[17][18]

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated, erythematous plaques covered with silvery scales commonly located on the elbows, knees, scalp, and lower back. Necrolytic acral erythema can be differentiated from psoriasis by its dark and verrucous scales and the absence of central clearing in the lesions. Histopathological examination may sometimes be required to confirm the diagnosis and exclude psoriasis.[19] Lichen simplex chronicus is another skin disorder characterized by thickened, scaly patches resulting from chronic rubbing or scratching. The lesions are typically well-defined, lichenified plaques that are intensely pruritic. Unlike necrolytic acral erythema, lichen simplex chronicus lacks necrotic features and systemic associations with HCV. However, late stages of necrolytic acral erythema may appear lichenified. Differentiation is based on a clinical history of chronic itching and physical examination, though a biopsy may be used to confirm the diagnosis if necessary.[20]

Erythrokeratoderma manifests as hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques, often in a geographic or linear pattern, and typically appears in infancy or childhood. Unlike necrolytic acral erythema, erythrokeratoderma typically shows symmetrical distribution and has a genetic basis.[21] Nummular eczema is characterized by coin-shaped, erythematous, and scaly plaques, often associated with itching and discomfort. The absence of well-defined lesions and verrucous scales observed in necrolytic acral erythema helps differentiate these conditions.[22] In addition, dermatophytosis presents with erythematous plaques with central clearing and peripheral scaling, typically caused by fungal infections. The absence of central clearing and the distinct histopathological features of necrolytic acral erythema assist in distinguishing it from dermatophytosis.[17][10][14]

Prognosis

The prognosis of necrolytic acral erythema varies and largely depends on recognizing the underlying cause, the effectiveness of the treatment administered, and a timely diagnosis. As necrolytic acral erythema is commonly associated with HCV infection, successful management of the underlying HCV can significantly improve skin lesions and overall outcomes.[23] Nonetheless, some reports indicate that necrolytic acral erythema lesions can reappear after stopping interferon treatment, and instances of necrolytic acral erythema recurrence might align with the return of liver disease symptoms and the recovery of HCV viral load. Moreover, mixed findings regarding the association between hepatic disease and skin burden have been reported.[24] The delay in diagnosing necrolytic acral erythema can negatively impact the prognosis due to its wide range of possible diagnoses and rarity.[24]

Complications

The complications of necrolytic acral erythema primarily arise from its persistent and recurrent lesions, which can be chronic, particularly if the underlying HCV infection is not adequately controlled.[6] These lesions can be painful, causing significant discomfort and impacting the patient's quality of life. Moreover, they are prone to secondary infections, especially if the skin barrier is compromised due to ulceration or scratching.

Chronic or recurrent necrolytic acral erythema lesions often lead to scarring and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which can be cosmetically concerning for patients. As necrolytic acral erythema typically affects the hands and feet, severe cases can impair the patient's mobility and ambulation, further diminishing their quality of life.[25]

Necrolytic acral erythema is closely linked to chronic HCV, a condition that can lead to severe complications, including cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma, if not adequately managed. This association underscores the importance of addressing the underlying infection in treating necrolytic acral erythema.[26] However, treatment challenges arise when HCV therapy is discontinued or proves ineffective, as this can lead to relapses of necrolytic acral erythema, complicating overall disease management.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective deterrence strategies include routine screening and early treatment of HCV to reduce the risk of developing necrolytic acral erythema.[10] Patient education should focus on raising awareness about the relationship between HCV and necrolytic acral erythema, emphasizing the importance of maintaining liver health and adhering to antiviral therapies.[27] Patients should be informed about the characteristic symptoms of necrolytic acral erythema, such as erythematous and scaly lesions on the extremities, to promote early detection and prompt medical consultation. Educating patients on skin care practices and the importance of follow-up visits can help manage symptoms and prevent complications. Comprehensive education empowers patients to participate actively in their care, improving outcomes and quality of life.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of necrolytic acral erythema requires a collaborative approach involving various healthcare professionals. Dermatologists and hepatologists are crucial in diagnosing necrolytic acral erythema and managing the associated HCV infection. At the same time, advanced practitioners and nurses play essential roles in educating patients, monitoring treatment adherence, and providing comprehensive skin care. Pharmacists ensure the safe and effective use of medications, such as antiviral therapies and zinc supplements, critical for treating necrolytic acral erythema. Interprofessional communication is crucial for successful management. Regular team meetings and coordination among team members ensure everyone is informed about the patient's status, treatment progress, and any complications, allowing for timely treatment adjustments.

Care coordination is also crucial in enhancing patient outcomes, including scheduling regular follow-ups to monitor the effectiveness of HCV treatment and the progression of skin lesions and coordinating necessary laboratory tests such as liver function tests and serum zinc levels. Advanced practitioners and nurses often act as case managers, ensuring patients adhere to their treatment regimens and attend scheduled appointments. A patient-centered approach is essential in managing necrolytic acral erythema. Engaging patients in their care by educating them about the connection between HCV and necrolytic acral erythema, stressing the importance of adhering to antiviral therapy and zinc supplementation, and teaching effective skin care practices can significantly improve outcomes. Adopting evidence-based strategies is critical for optimizing necrolytic acral erythema management. Antiviral treatments such as ribavirin and interferon-alpha have shown improvement in necrolytic acral erythema lesions, whereas zinc supplementation has also been effective, even in the absence of zinc deficiency. The healthcare team can significantly enhance patient outcomes and overall team performance in managing necrolytic acral erythema by focusing on interprofessional collaboration, effective communication, coordinated care, patient-centered approaches, and evidence-based strategies. Regularly updating care protocols based on the latest research ensures the team remains at the forefront of effective necrolytic acral erythema management, ultimately reducing morbidity and improving the quality of life for patients.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Necrolytic Acral Erythema Histopathology. Histologically, the epidermis shows thickening (acanthosis) and intercellular edema (spongiosis), accompanied by superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate resembling nummular dermatitis. The accumulation of necrotic keratinocytes can lead to the formation of clefts in the upper epidermis.

Contributed by N Sathe, MD

References

Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, Hafez AM, Hiatt KM, Smoller BR, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005 Aug:53(2):247-51 [PubMed PMID: 16021118]

Garg B, Arbabi A, Kirkland PA. Extrahepatic Manifestations of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection. Cureus. 2024 Mar:16(3):e57343. doi: 10.7759/cureus.57343. Epub 2024 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 38562366]

Yost JM, Boyd KP, Patel RR, Ramachandran S, Franks AG Jr. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatology online journal. 2013 Dec 16:19(12):20709 [PubMed PMID: 24365000]

Srisuwanwattana P, Vachiramon V. Necrolytic Acral Erythema in Seronegative Hepatitis C. Case reports in dermatology. 2017 Jan-Apr:9(1):69-73. doi: 10.1159/000458406. Epub 2017 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 28611625]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEl-Ghandour TM, Sakr MA, El-Sebai H, El-Gammal TF, El-Sayed MH. Necrolytic acral erythema in Egyptian patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2006 Jul:21(7):1200-6 [PubMed PMID: 16824076]

El-Darouti MA, Mashaly HM, El-Nabarawy E, Eissa AM, Abdel-Halim MR, Fawzi MM, El-Eishi NH, Tawfik SO, Zaki NS, Zidan AZ, Fawzi M, Abdelaziz M, Fawzi MM, Shaker OG. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and necrolytic acral erythema in patients with hepatitis C infection: do viral load and viral genotype play a role? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010 Aug:63(2):259-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.050. Epub 2010 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 20462666]

Inamadar AC, Shivanna R, Ankad BS. Necrolytic Acral Erythema: Current Insights. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2020:13():275-281. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S189175. Epub 2020 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 32308461]

DiGuilio KM, Rybakovsky E, Abdavies R, Chamoun R, Flounders CA, Shepley-McTaggart A, Harty RN, Mullin JM. Micronutrient Improvement of Epithelial Barrier Function in Various Disease States: A Case for Adjuvant Therapy. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022 Mar 10:23(6):. doi: 10.3390/ijms23062995. Epub 2022 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 35328419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJagadeesan S, Kaliyadan F. Acrodermatitis Enteropathica. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722865]

Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009 Jun:83(6):309-14 [PubMed PMID: 19681342]

Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, Hafez AM, Hiatt KM, Smoller BR, Horn TD. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. The Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society. 2004 Apr:100(10):354-5 [PubMed PMID: 15080276]

Jakubovic BD, Zipursky JS, Wong N, McCall M, Jakubovic HR, Chien V. Zinc deficiency presenting with necrolytic acral erythema and coma. The American journal of medicine. 2015 Aug:128(8):e3-4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.03.022. Epub 2015 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 25863150]

Moneib HA, Salem SA, Darwish MM. Evaluation of zinc level in skin of patients with necrolytic acral erythema. The British journal of dermatology. 2010 Sep:163(3):476-80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09820.x. Epub 2010 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 20426777]

Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Archives of dermatology. 2005 Jan:141(1):85-7 [PubMed PMID: 15655150]

Manzur A, Siddiqui AH. Necrolytic acral erythema: successful treatment with topical tacrolimus ointment. International journal of dermatology. 2008 Oct:47(10):1073-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03710.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18986360]

Raphael BA, Dorey-Stein ZL, Lott J, Amorosa V, Lo Re V 3rd, Kovarik C. Low prevalence of necrolytic acral erythema in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012 Nov:67(5):962-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.11.963. Epub 2012 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 22325461]

Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, El-Assar O, Assaf M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? International journal of dermatology. 2005 Nov:44(11):916-21 [PubMed PMID: 16336523]

Santaliz-Ruiz LE 4th, Marrero-Pérez AC, Sánchez-Pont J, Nevárez-Pomales O. Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica with concomitant acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica in a patient with maple syrup urine disease. JAAD case reports. 2024 Mar:45():7-10. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.12.009. Epub 2024 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 38333677]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet (London, England). 2015 Sep 5:386(9997):983-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7. Epub 2015 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 26025581]

Ju T, Vander Does A, Mohsin N, Yosipovitch G. Lichen Simplex Chronicus Itch: An Update. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2022 Oct 19:102():adv00796. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.4367. Epub 2022 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 36250769]

Croitoru D, Lu JD, Lara-Corrales I, Kannu P, Pope E. ELOVL4 with erythrokeratoderma: A pediatric case and emerging genodermatosis. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2021 May:185(5):1619-1623. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.62136. Epub 2021 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 33655653]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHüppop F, Dähnhardt-Pfeiffer S, Fölster-Holst R. Characterization of Classical Flexural and Nummular Forms of Atopic Dermatitis in Childhood with Regard to Anamnestic, Clinical and Epidermal Barrier Aspects. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2022 Mar 8:102():adv00664. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v101.979. Epub 2022 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 34935994]

el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. International journal of dermatology. 1996 Apr:35(4):252-6 [PubMed PMID: 8786182]

Bentley D, Andea A, Holzer A, Elewski B. Lack of classic histology should not prevent diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009 Mar:60(3):504-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.046. Epub 2008 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 18992966]

Oikonomou KG, Sarpel D, Abrams-Downey A, Mubasher A, Dieterich DT. Necrolytic acral erythema in a human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus coinfected patient: A case report. World journal of hepatology. 2019 Feb 27:11(2):226-233. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i2.226. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30820272]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFarooq HZ, James M, Abbott J, Oyibo P, Divall P, Choudhry N, Foster GR. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C genotype 3 infection: A systematic review. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2024 Apr 15:16(4):1596-1612. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1596. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38660636]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWiznia LE, Laird ME, Franks AG Jr. Hepatitis C virus and its cutaneous manifestations: treatment in the direct-acting antiviral era. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2017 Aug:31(8):1260-1270. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14186. Epub 2017 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 28252812]