Introduction

Xylazine is a non-narcotic compound utilized for sedation, pain relief, and muscle relaxation in veterinary medicine, where it is often referred to as "anestesia de caballo" or "horse anesthetic."[1][2] Also known as N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-thiazin-2-amine, xylazine is a clonidine analog discovered by Farbenfabriken Bayer in 1962 in Germany promoted for use as an antihypertensive.[3] Approval was not granted for human use as an antihypertensive due to profound hypotension and excessive central nervous system depression.[4] Xylazine was later introduced as a sedative, emetic, analgesic, and muscle relaxant for veterinary use. The use of xylazine in animals was first reported in the late 1960s, and it is currently approved for use as a nonopioid tranquilizer in veterinary medicine.[3][5] Xylazine is frequently used with ketamine as an anesthetic agent for experimental studies involving dogs, cats, horses, rabbits, and rats.

Xylazine emerged as a popular illegal substance among those who inject drugs in Puerto Rico in the early 2000s. Currently, there is limited information about the unlawful consumption, geographic prevalence, and immediate or long-term effects of xylazine on humans. Recently, xylazine misuse has surged in the northeastern United States, spreading across many states, as evidenced by the rising number of samples testing positive for the drug.

In Philadelphia, xylazine is popularly referred to as "tranq"; when xylazine is mixed with more prevalent illegal opioids like heroin or fentanyl, the mixture is called "tranq dope."[6] Xylazine is frequently combined with synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, in the unregulated market. Additionally, xylazine has been found alongside cocaine and methamphetamine and, more recently, mixed with oxycodone and alprazolam. Xylazine was reportedly diverted from the veterinary market to the recreational drug market in Puerto Rico.

Xylazine has spread rapidly due to several factors, including cost-cutting, an increase in its addictive properties, and its ability to extend the duration of the opioid with which it is combined. Xylazine poses a challenge to the United States healthcare system and those who use it knowingly or unknowingly due to its benefits to the illegal drug industry, a lack of information, and the absence of an approved antidote.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

For veterinary usage, xylazine is available as a liquid solution for injection in concentrations of 20 mg/mL, 100 mg/mL, and 300 mg/mL. The liquid solution may be dried into a powder or salted. The powder may appear white or brown.

Xylazine may be added to other illicit substances for many reasons.

The powder can be used as a cutting agent in street drugs like heroin and fentanyl to increase the bulk of those drugs. It may be challenging to distinguish xylazine solely based on appearance since it can be blended with other powders or crushed into tablets to adulterate a drug supply. The availability, low cost, and ability of xylazine to potentiate the opioid effect make it a profitable addition to the opioid supply, decreasing the net amount of heroin or fentanyl sold and improving profits.[7] Although some individuals intentionally seek out xylazine-adultered opioids, a survey of the popular social media website Reddit found that xylazine is considered an unwanted adulterant in most situations.[8] When combined with stimulants, xylazine can decrease the adverse effects and withdrawal symptoms of the stimulant.[9]

Acute xylazine toxicity can occur with an overdose of xylazine-mixed illicit substances, leading to severe central nervous system (CNS) depression, respiratory depression, bradycardia, hypotension, and, in extreme cases, cardiac arrest. Long-term use of xylazine-mixed illicit substances can result in cumulative toxic effects, leading to chronic complications in various organ systems, including chronic wounds and ulcers on the skin. The etiology of xylazine use in humans is complex, and further research is needed to understand the factors contributing to its abuse.

Epidemiology

The State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) has identified xylazine as an emerging adulterant in illicit drug mixtures, amplifying the already devastating opioid overdose crisis. Xylazine use substantially increased before adequate research on its effects was completed.

Before 2000, reports of xylazine intoxication in humans were infrequent.[4] It was found initially to be a more common additive in Puerto Rico and then more commonly seen in some Puerto Rican communities within the continental United States.[2][10] Persons who inject drugs (PWID) and public health professionals have observed xylazine as an increasingly common additive in the street opioid supply of Philadelphia since the mid-2010s.[6]

In 2014, xylazine was reported as an adulterant in recreational drugs such as heroin or combined opioid-stimulants, commonly called a "speedball." From 2015-2021, xylazine was reported to be coadministered primarily with fentanyl and cocaine, in addition to benzodiazepines, methamphetamine, and heroin. In Canada, flualprazolam, flubromazepam, flubromazolam, and etizolam were the most commonly co-occurring nonmedical benzodiazepines. A 2022 study by the Rhode Island government reported that in addition to cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl, xylazine was combined with reasonably prevalent drugs of abuse like Percocet (oxycodone plus acetaminophen) and Xanax (alprazolam). This pattern illustrates that xylazine is being combined with an increasing number of substances.

Furthermore, recent reports from Connecticut implicated xylazine in a rising fraction of overdose deaths during 2019–2020.[11] A study published in 2021 analyzed data from 38 states and Washington, D.C., and revealed that xylazine was present in 1.8% of overdose-related deaths in 2019.[12] Another study revealed that xylazine existed in ten jurisdictions throughout the four United States Census regions. Among these locations, Philadelphia had the highest prevalence of xylazine-related deaths at 25.8%, followed by Maryland at 19.3%, and Connecticut at 10.2%.[13] In 2021, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health reported that 91% of samples of purported heroin or fentanyl from the local area contained xylazine, making it the most common adulterant in the drug supply.

According to a study conducted in 2023, xylazine was detected in 413 out of 59,498 samples collected from individuals aged 20 to 73 across 25 states where physicians ordered testing. The study revealed that the most frequently identified substances were fentanyl (96%), buprenorphine, nicotine metabolites, cocaine, naloxone, D-methamphetamine, and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Additionally, xylazine was found to be prevalent. Among the designer benzodiazepines, etizolam and clonazolam metabolites were the most commonly detected.[9] Ethnographic accounts indicate that xylazine poses grave risks for PWID. Many recently published studies suggest that the percentage of deaths involving xylazine or found to have xylazine along with other drugs of abuse and overdose is steeply rising.

Pathophysiology

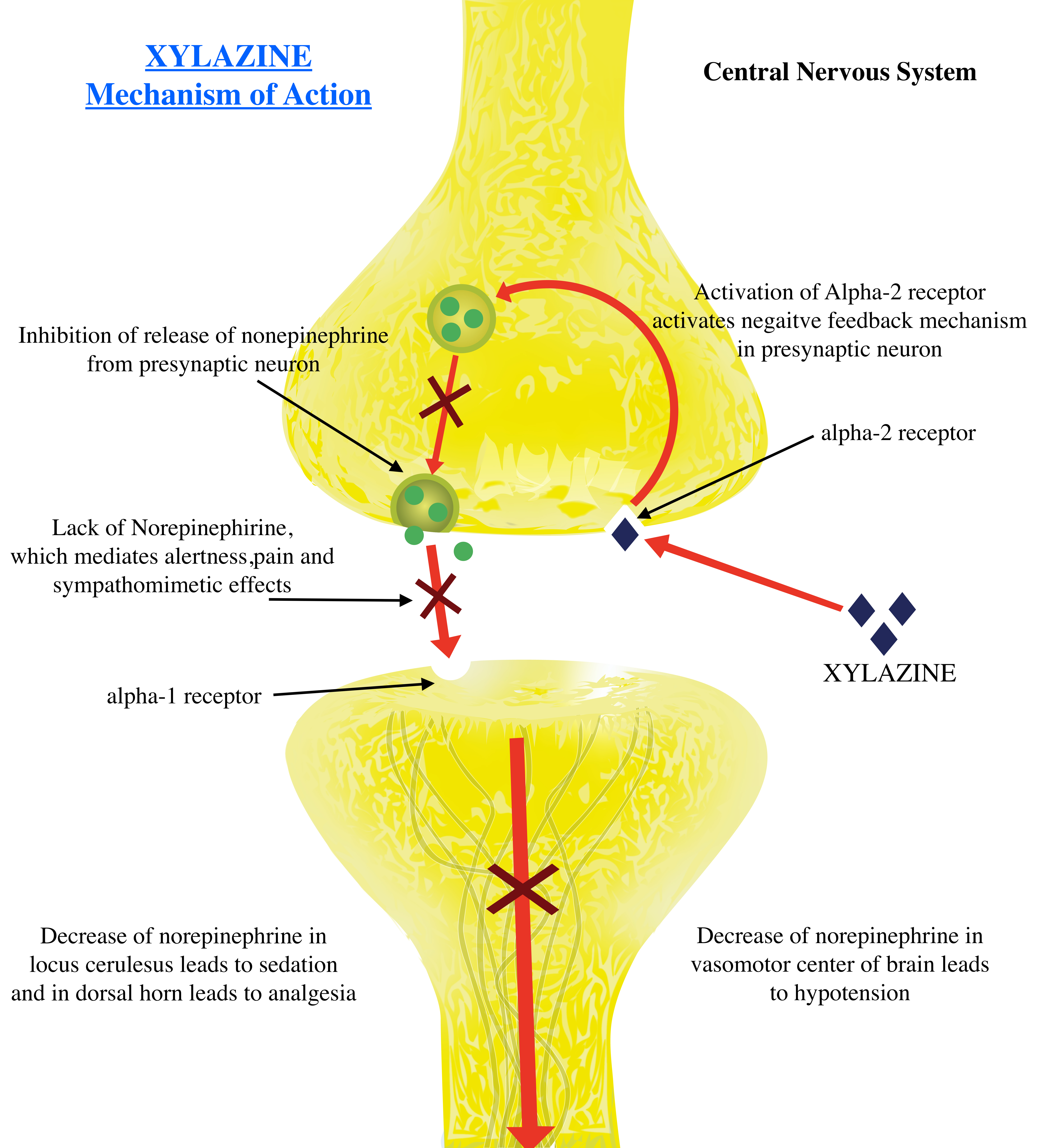

The chemical structure of xylazine closely resembles that of phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, and clonidine. Xylazine is in the same drug class as clonidine, lofexidine, and dexmedetomidine and functions as an alpha-2 receptor agonist. Alpha-2 adrenoreceptors are found on the presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons of the central and peripheral nervous systems and are activated by norepinephrine and epinephrine. When the presynaptic receptors are activated, the release of norepinephrine onto the alpha-1 receptor in the postsynaptic neuron is inhibited due to a negative feedback mechanism. This lack of norepinephrine activity leads to the sympatholytic effects of hypotension, bradycardia, sedation, analgesia, and muscle relaxation. However, activation of postsynaptic receptors leads to sympathomimetic effects. Xylazine has a high affinity for presynaptic alpha-2 receptors, making its sympatholytic effects more pronounced clinically (see Image. Xylazine Mechanism of Action).

There are 3 alpha-2 adrenoreceptor subtypes: alpha-2a, alpha-2b, and alpha-2c. The activation of presynaptic alpha-2a and alpha-2c subtypes mediate the sympatholytic effects of sedation via the locus ceruleus and analgesia via the dorsal horn.[14] In contrast, the alpha-2b subtype, mainly located in vascular smooth muscles, mediates vasoconstriction and hypertension. The selectivity of xylazine for alpha-2/alpha-1 is 160:1; its selectivity and affinity for alpha-2a and alpha-2b are unclear.[15]

However, in animal models, high doses of xylazine lead to intense alpha-1 and alpha-2b receptor activation, which can lead to adverse sympathomimetic effects such as hypertensive emergencies, cerebrovascular accidents, and myocardial infarctions. The direct vasoconstrictive effect of xylazine activating peripheral alpha-2b receptors in the vascular smooth muscles, leading to decreased skin perfusion, is thought to be the pathophysiology of skin ulcers that develop due to chronic use.[14] This vascular effect and resultant decreased skin perfusion are irrespective of the route of xylazine use; ulcerations can occur remotely from an injection site.[16][7] In addition, resultant hypotension, bradycardia, and respiratory depression further decrease tissue perfusion, decreasing wound healing and increasing the risk of secondary infection.

Histopathology

A single case report presents the findings of a punch biopsy of a patient presenting with an ulcerated lesion on the thigh after using intravenous fentanyl and xylazine. Histopathological evaluation revealed epidermal necrosis with focal fibrin thrombi within superficial small vessels; vasculitis was absent. However, this is a single case report, and more literature needs to be presented before definitive histopathological findings can be described for these lesions.[17]

Toxicokinetics

Xylazine or xylazine-containing drugs can be injected into muscles or veins, insufflated, ingested, or smoked.[11] While the route of administration of xylazine is dictated by the substance it is mixed with, xylazine is known to exert its effects regardless of the route of administration. Pharmaceutical, pharmacokinetic, and toxicokinetic data for xylazine is limited. In veterinary medicine, these kinetic parameters are well-established for dogs, sheep, horses, and cattle. There are no significant kinetic differences among species.[4]

Xylazine is quickly absorbed.[18] Xylazine has a large volume of distribution due to its lipophilicity and is rapidly concentrated in the CNS and kidney. Xylazine is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes in the liver and excreted through the kidney as 2,6-xylidine. Xylazine is quickly eliminated from the body, with an elimination half-life of 23 to 50 minutes. Xylazine is rapidly metabolized, and there is minimal elimination of intact xylazine by the kidney. In animal models, total drug elimination after administration of a therapeutic dose of xylazine for sedation occurs over 10 to 15 hours.[4]

Depending on the dosage, route of administration, and combination with other substances, the effects of xylazine may begin within minutes and last for 8 or more hours. Xylazine can cause toxicity and death in humans at dosages ranging from 40 to 2400 mg, with plasma concentrations in nonfatal cases ranging from 0.03 to 4.6 mg/L and from trace to 16 mg/L in fatal cases.[19][20] This significant overlap between fatal and nonfatal doses indicates that there may be no "safe" blood concentration of xylazine.[4] Due to a lack of clear evidence regarding the pharmacokinetics of xylazine in humans, a preemptive correlation with animal studies is required; however, the authenticity of this correlation requires validation with further studies in humans.

History and Physical

Identification of xylazine toxicity is difficult due to its use as an adulterant and the inherent nature of polysubstance use. It is challenging to identify xylazine toxicity solely based on history and physical examination; many other substances with their specific toxidrome may be present. At this time, prudence dictates a low threshold of suspicion for coadministration of xylazine and any available illicit drug.

Xylazine toxicity is characterized by CNS depression. Symptoms may include a "high" feeling, sedation, dry mouth, dysarthria, hyporeflexia, disorientation, dysmetria, miosis, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, and hyperglycemia. When combined with other CNS depressants such as opioids, benzodiazepines, or alcohol, xylazine overdose causes severe CNS depression with signs and symptoms of obtundation, coma, muscle relaxation, hypotension or hypertension, respiratory depression, areflexia, asthenia or apnea, cardiac arrhythmias or cardiac arrest.[4]

The xylazine high may last up to 6 hours, and users often feel driven to look for their next dosage while still high. This makes abstinence difficult. The lack of effective withdrawal treatment makes abstinence difficult, as standard medication-assisted therapies for opioid use disorder do not mitigate xylazine withdrawal symptoms.[7] The chronic use of heroin and fentanyl mixed with xylazine can lead to deep skin ulcers, abscesses, and infections.[16] These xylazine-associated wounds may increase the risk of bacteremia, endocarditis, sepsis, limb amputation, and death. Any patient with a nonhealing ulcer, regardless of the use of injection as the route of administration, should be assessed for xylazine use.

Fentanyl is the drug most commonly combined with xylazine. Patients under the influence of this combination of substances will present with opioid toxidrome, including miosis with CNS and respiratory depression. Nystagmus may be seen due to the xylazine. Fentanyl and xylazine have an additive effect on the CNS and respiratory depression that can lead to arrest and death. Patients exhibiting signs of a fentanyl overdose who have shown little to no improvement with the administration of naloxone should be suspected of a xylazine overdose or another etiology of their condition.

Patients using illicit substances should be educated on the signs, symptoms, and potential consequences of xylazine overdose. Patients should also be educated on the benefit of naloxone administration in cases of opioid overdose, even if the opioid is mixed with xylazine. While naloxone will not reverse the xylazine toxidrome, reversal of the opioid toxidrome can decrease overall mortality.

Evaluation

Evaluating a patient with suspected xylazine intoxication is similar to any other patient presenting after an overdose. The initial priority is establishing and maintaining an airway and ensuring adequate breathing and circulation. A mental status assessment should be performed, and a comprehensive medical history should be obtained if possible. A complete physical examination, bedside glucose, and, if applicable, a pregnancy test should be completed.

In clinical settings, xylazine remains undetected in the most frequently performed urine drug screenings (UDS). These drug screenings are presumptive and use an immunoassay technique to test for the five most common substances of abuse: opiates, cannabinoids, amphetamines, cocaine, and phencyclidine (PCP).[21] Individuals treated with prescription pain drugs are tested additionally for benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and methadone using specialized testing methods. In cases of overdose, levels of lysergic acid (LSD), propoxyphene, buprenorphine, tramadol, fentanyl, and oxycodone can be assessed.[22]

The presence of xylazine in urine samples must be confirmed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. However, chromatography testing procedures are more expensive than typical immunoassays and do not result for 7 to 8 days.[23] Such testing would not provide real-time assistance with the care of an intoxicated patient. An experimental model comparing human and rat xylazine metabolites found no differences between the species; this may be an aid in developing urine detection assays in humans.[24] The rapid clearance of xylazine increases the possibility of false negative test results, complicating the development of effective testing methods. Creating xylazine detection assays that enhance sensitivity while lowering costs and processing times will require further research.

Due to the ongoing xylazine crisis, lateral flow immunoassay has been used to develop testing strips for xylazine with a detection sensitivity of up to 1000 ng/mL. The strips are used to test for xylazine within the drug supply. Testing strips used by patients with substance use disorder are available through common online marketplaces and harm-reduction programs but are currently rare in the healthcare setting. The use of this method in the healthcare setting would likely be limited; the ingested drug is rarely close to hand in the acute setting. However, these strips can play an eminent role as a harm-reduction tool.[25]

Treatment / Management

Management of Acute Xylazine Toxicity

Persons suspected of xylazine overdose in the field should be administered naloxone and placed in the "recovery position." Proper patient positioning is crucial in drug overdoses and is designed to maintain a clear airway and prevent aspiration in an unconscious, independently breathing person. The recovery position also prevents the person from rolling onto their stomach or back, which could restrict their breathing.

Use the following steps to place a person in the recovery position:

- Kneel beside the patient

- Extend the patient's arm that is closest to you above their head

- Fold their other arm across their body, placing the back of their hand against the cheek closest to you

- Bend the knee farthest from you and place the foot flat on the ground

- Roll the patient toward you onto their side

- Tilt their head back to open the airway; check for airway obstruction; clear any obstruction present if possible

- Adjust their top leg so the hip and knee are bent at right angles

- Monitor the patient until help arrives, performing airway maneuvers such as head or chin tilt and rescue breathing as needed

- Be prepared to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation as needed

As of June 2023, no pharmacological antidote for xylazine intoxication has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Management of xylazine intoxication involves supportive care, monitoring for adverse effects, and interventional management as symptoms present. Supportive care includes supplemental oxygen and airway management, intravenous fluid administration, vasopressor administration for hemodynamic instability, assessment and replenishment of electrolytes to prevent dysrhythmias, and management of hyperglycemia. The use of medications inducing CNS depression should be avoided. Naloxone should be administered to treat any concomitant opioid toxidrome. Prolonged sedation is a risk factor for thromboembolic disease, and patients should be monitored accordingly. Hemodialysis may not be effective in removing xylazine from the blood due to its lipophilic property.

Routine Care for Xylazine-induced Skin Ulcers

Routine wound care for xylazine-induced skin lesions comprises wound cleansing, evaluating potential secondary infection, applying a nonadherent gauze such as Xeroform to the wound bed, and applying a topical ointment. Daily dressing changes with layered dressings are optimum. Debridement may be necessary in cases where nonviable tissue covers the ulcer bed. Full-thickness wounds may require reconstruction or, in severe cases, limb amputation. Antibiotic coverage for secondary infection must cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and coverage for group A streptococci should be considered.

Management of Xylazine Withdrawal Symptoms

Withdrawal symptoms have been reported in cases of chronic xylazine use. However, the literature regarding withdrawal symptom management is minimal. A single case report describes managing xylazine withdrawal using combined tizanidine, phenobarbital, and dexmedetomidine infusions followed by clonidine; the patient was discharged on clonidine, buprenorphine, and gabapentin. There is a possibility that these symptoms may not be due to isolated xylazine withdrawal.[26] (B3)

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health released recommendations for managing and alleviating xylazine withdrawal symptoms. The suggested approach includes replacement therapy with alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as clonidine, dexmedetomidine, tizanidine, or guanfacine paired with symptom management for pain using short-acting opioids, ketamine, gabapentin, ketorolac, acetaminophen, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Concomitant insomnia can be managed with trazodone, quetiapine, or mirtazapine; anxiety can be addressed with hydroxyzine or benzodiazepines. Anxiety, irritability, and restlessness from xylazine withdrawal overlap with symptoms of opioid withdrawal; any coexisting opioid withdrawal symptoms must be addressed promptly. As xylazine is not an opioid, standard medication-assisted therapies such as methadone and buprenorphine will not be effective.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute conditions similar to xylazine overdose include syncope, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, seizure disorders, and cerebrovascular accidents.

Various toxidromes share the characteristics of xylazine overdose.

Opioid overdose is the most common coexisting diagnosis. Naloxone can reverse opioid overdose but will not affect the clinical effects of xylazine. Overlooking concomitant opioid overdoses can result in fatal outcomes. Benzodiazepine overdose can lead to CNS depression. However, compared to xylazine toxicity, there is less respiratory depression and little cardiovascular derangement. Other toxidromes that may mimic xylazine toxicity include barbiturates and ethyl alcohol.

Xylazine is an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, and an overdose of other drugs of this class, such as clonidine, tizanidine, guanfacine, and dexmedetomidine, will present similarly to xylazine overdose. Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers can also cause bradycardia and hypotension; calcium channel blockers may also induce hyperglycemia.

Skin Lesions

Skin ulcers resulting from xylazine use may result regardless of the method of drug use. Consideration of other etiologies of the lesion is a must, and multifactorial etiologies must be considered. A comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing with wound cultures, biopsies, or imaging studies may be necessary to correctly determine the etiology of any ulcerated skin lesion.

Skin lesions may occur secondary to a host of infectious processes; bacterial cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, bullous impetigo, fungal dermatoses, and viral infections are common. Ulcerated skin lesions may also be due to heroin or methamphetamine use. Cocaine adulterated with levamisole may induce ulcerated skin lesions, most often on the ears and nose.

Vascular pathologies such as chronic venous stasis, peripheral arterial disease, poorly-controlled diabetes, vasculitides, and autoimmune diseases may result in ulcerated skin lesions.

Pressure ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, and advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin may also rarely present as chronic nonhealing skin ulcers.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Developing a xylazine-specific antidote is the need of the hour. Some case reports and studies describe efforts to identify an antidote for xylazine; an antidote that meets the FDA-approval standards remains elusive. Although the results from these studies cannot be used as clinical treatment guidelines, they can guide antidote research and development.

For example, atropine reversed xylazine-induced bradycardia and hypotension in humans in some case reports.[27] The alpha-2 antagonist yohimbine was used alone or with 4-aminopyridine in several animal studies to block the effects of xylazine and was used to antagonize the sedative effects of xylazine in humans in doses up to 0.125 mg/kg. Yohimbine can be effective within 15 minutes of intramuscular administration and 1 to 2 minutes of intravascular administration.[28]

Tolazoline may be administered in cases of unresponsive bradycardia and hypotension.[29] However, tolazoline is known to cause hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmias and may be used only in cases unresponsive to other interventions. Atipamezole, a potent alpha-2 antagonist approved for use in humans from 1970 to 2017, is no longer available; when comparing the dose requirements in humans and animals, studies suggest atipamezole may be a life-saving drug in overdose emergencies.[30]

Xylazine use is spreading rapidly. To effectively reduce harm, any xylazine-specific antidote must be readily available, safer than xylazine itself, conducive to mass production, efficacious, and nonaddictive. Ideally, such an antidote would also be compatible with or effective against the concomitant opioids usually mixed with xylazine.

Prognosis

The clinical implications of human use of xylazine are significant, with a range of potential health outcomes. Various factors influence the prognosis of individuals with xylazine toxicity, including the dose of xylazine, the fraction of xylazine if it was mixed with other opioids, the overall health condition of the individual, and the promptness of medical intervention. Early identification of symptoms and the time to medical intervention can determine the outcome; timely medical assistance and avoidance of severe respiratory depression or other complications portend a more favorable recovery. However, sustained xylazine exposure or use can precipitate grave health outcomes, including death.

Avoiding xylazine use and providing prompt and appropriate treatment for xylazine-induced skin ulcers may result in wound healing. However, if the ulcers are not adequately cared for and get infected, the chances of acquiring sepsis from infection, the need for limb amputation, and mortality are very high.

Complications

An overdose of xylazine or its toxicity may have substantial clinical implications, including death. The consequences specific to each organ system have not been adequately studied in humans. The few existing studies on humans and animals indicate potentially life-threatening complications of xylazine use, including biventricular failure, pulmonary edema, cardiac necrosis, valvular dysfunction, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

The primary metabolite of xylazine, 2,6-xylidine, has carcinogenic and genotoxic effects; long-term users of xylazine appear to be at increased risk for malignancies.[31] One study showed that xylazine increases the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, increasing DNA fragmentation. More studies on this mechanism are needed, as this process can induce or potentiate malignancy.[20]

There are no human data on the effect of xylazine on embryogenesis and pregnancy. Studies performed in the veterinary field have revealed increased uterine contractions, decreased uterine blood flow, and fetal loss when xylazine is used in pregnant cattle and goats.[3][32]

It has been reported that xylazine addiction is even stronger than opioid addiction, including fentanyl. The prolonged effects of xylazine may promote addiction and dependency, complicating recovery.[7] In addition, there are no effective treatments for xylazine withdrawal or prolonged therapy for xylazine addiction.

Consultations

For patients who use xylazine but do not show signs of acute toxicity, primary consultation with a mental health professional or addiction specialist. A social worker may be needed to evaluate living conditions, support networks, and resource access barriers. If chronic health issues are suspected due to xylazine use, outpatient management by other specialties, such as cardiology, neurology, or pulmonology, may be required.

Symptom severity will determine the required consulting services when managing xylazine poisoning and toxicity.

The first step in management would be to call a poison control center; a toxicology specialist can recommend the best treatment method. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, has severe respiratory depression with impending respiratory failure, or requires closer monitoring and extensive nursing care based on real-time clinical judgment, the critical care team or intensivist should be consulted.

Subspecialty consultation is dictated by patient symptomatology. Severe bradycardia, arrhythmia, heart failure, or cardiomyopathy suspected or resulting from xylazine usage will necessitate the expertise of a cardiologist. Substantial central nervous system depression, seizures, or cardiac arrest leading to anoxic brain damage will warrant neurology consultation.

If the use of xylazine is symptomatic of a broader substance abuse problem, or if the xylazine was taken as an intentional overdose, a psychiatrist, preferably one specializing in addiction, should be consulted to address the underlying cause and recommend appropriate treatment techniques.

In patients with ulcers, wounds, or abscesses due to xylazine, wound care specialists might be required to perform daily dressing changes and assess for indications for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The infectious disease team may be consulted to guide antibiotic therapy. If debridement or amputation is required, surgical consultation is required.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The increasing prevalence of xylazine toxicity in humans is an alarming trend in an era of increasing substance abuse and related fatalities. Deterrence and patient education are essential pillars in the fight against xylazine abuse and toxicity.

Deterrence

Deterrence represents a complex and multifaceted strategy that involves law enforcement, regulatory bodies, healthcare professionals, and community stakeholders.

- Law enforcement and regulatory bodies: Strengthening measures against the unlawful diversion of xylazine is crucial, and it can be accomplished through enhancing surveillance and tracking techniques, imposing stricter sanctions on illicit distribution, and fostering international collaboration to deter cross-border trafficking. When considering the risks of xylazine being diverted and the benefits of using it as an anesthetic in veterinary medicine, it is possible that completely halting the production of this drug, even for veterinary use, could have benefits for humans. It may be worth exploring alternative anesthetics. Government officials and policymakers can help establish safer supply programs to reduce the number of individuals who rely on the unregulated and hazardous drug supply and are unintentionally exposed to xylazine.

- Healthcare professionals: Healthcare providers, particularly veterinarians worldwide, have a crucial role in preventing drug misuse, as xylazine initially entered the human market through redirection from veterinary use rather than illicit manufacturing. These providers can help identify and intervene in substance misuse and redirection cases. Primary care physicians can also reduce drug addiction by screening patients for substance use disorders and referring them promptly to addiction treatment services.

- Community stakeholders: Community-led initiatives can also contribute significantly to deterrence efforts. Building awareness about the dangers of drug misuse, providing resources for the safe disposal of unused veterinary medications, and promoting community-based programs for educating risk groups about xylazine and its harmful effects and drug addiction recovery are all vital elements of a comprehensive deterrence strategy.

Patient Education

In addition to deterrence, patient education is critical to our efforts against xylazine misuse and toxicity.

- Risks and consequences: Education through healthcare providers, community members, and government agencies should focus on the risks and potential consequences of xylazine misuse. This education should include physical health impacts like respiratory depression, hypotension, addiction risk, dependence risk, and fatal overdose. The fact that xylazine is not intended for human use and has unknown long-term effects on humans should be heavily emphasized.

- Recognition of symptoms: It is important to educate those at risk and individuals who inject drugs on the signs of xylazine toxicity. This information should include distinguishing between feeling high and experiencing central nervous system depression, respiratory depression, and low blood pressure. This education can help reduce the use of xylazine and enable early recognition of harmful effects in individuals and their friends who inject toxic drugs. With thorough education, timely medical intervention can be sought during an overdose.

- Safe practices: For those with occupational contact with xylazine, education about safe handling, storage, and disposal practices can help prevent unintentional exposure and diversion.

- Resources and support: Patients should be informed about resources for addiction help. This information should include local addiction treatment services, support groups, hotlines, and support apps like the Brave app.

Harm-reduction Strategies

In settings where complete cessation of drug use is not immediately achievable, harm-reduction strategies should be discussed. Two essential harm reduction strategies are wound care and safer drug use. The wound care strategy involves providing individual wound care supplies, gloves, and hand sanitizer to a person caring for their wounds. Safer drug use strategies include PWID avoiding injecting into wounds, swabbing skin with alcohol before injecting and avoiding use when alone, flushing nasal passages before and after using sterile water or saline if sniffing or snorting, and healthcare agencies providing patients with sterile syringes, naloxone with administration training, and providing fentanyl test strips with training on using and interpreting results as part of supervised consumption services.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Adopting a collaborative, interprofessional approach utilizing the expertise of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must be efficiently harnessed to deliver patient-centered care, improve safety, and enhance team performance in fighting xylazine use, which can potentially become another drug catastrophe like ketamine and fentanyl. Skills, strategies, ethics, responsibilities, and communication measures should be considered in this context.

Skills and Strategy

- Early detection and early intervention: Physicians and advanced practice providers, particularly those in emergency medicine, primary care, and addiction specialties, should be skilled in recognizing the signs of xylazine overdose and toxicity and be prepared to initiate immediate interventions. This includes conducting efficient patient screenings for substance use disorders and providing or referring for appropriate treatment and drug rehabilitation facilities.

- Updated knowledge base: As xylazine is relatively new in the field of toxicology and drug addiction, it is essential to educate all healthcare professionals about what xylazine is and facilitate an understanding of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, clinical features, evaluation, and management of xylazine toxicity. The interaction between xylazine and opioids must be stressed; the need for naloxone, despite its ineffectiveness against xylazine, is imperative. Healthcare administrators should encourage their staff to attend continuing medical education activities on xylazine.

- Education: Healthcare professionals with direct patient interaction should be trained to educate patients about the risks of xylazine misuse and provide them with resources for addiction help.

- Trauma-informed Care: All healthcare team members should be skilled in providing trauma-informed care to acknowledge the complex history of physical, emotional, and psychological trauma in individuals with substance use disorders.

- Social media presence: Increasing the presence of healthcare personnel on social media to provide updates and essential information about xylazine trends, toxicity, and mitigation strategies will substantially impact harm prevention and reduction.

Ethics and Responsibilities

- Non-judgmental care with confidentiality: The stigma and guilt associated with substance abuse and embarrassment related to xylazine-associated wounds can delay treatment and worsen health outcomes. Hence, patients presenting with substance misuse or related toxicity should be treated with respect and without judgment, in line with the principles of medical ethics. Healthcare professionals should guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of patient information.

- Advocacy: Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to advocate for their patients. This includes lobbying for better access to addiction treatment services and the availability of harm reduction tools like naloxone and drug testing strips.

Interprofessional Communication and Care Coordination

- Communication: Effective interprofessional communication is critical to managing complex cases of xylazine toxicity. Regular meetings, patient case conferences, and shared electronic health records can facilitate seamless communication.

- Care coordination: Managing xylazine toxicity requires the input of various healthcare professionals. Care coordination ensures that everyone involved in the patient's care is on the same page, reducing the risk of conflicting advice or treatments.

- Referrals and follow-up appointments: Timely referrals to addiction specialists and diligent follow-up care are essential to ensure patients receive the needed help.

Investing in these areas can enhance healthcare team outcomes in the face of xylazine toxicity and address the broader issue of substance misuse in our communities. Ultimately, this can help us provide the highest standard of care to all patients, especially the most vulnerable.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Xylazine-induced Upper Extremity Wounds. Wounds on the back of upper extremities in a patient misusing fentanyl contaminated with xylazine. The patient had a history of intranasal use only and denied intravenous use. Contributed by Bhavani Nagendra Papudesi, MD. Image provided with informed patient consent.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Nunez J, DeJoseph ME, Gill JR. Xylazine, a Veterinary Tranquilizer, Detected in 42 Accidental Fentanyl Intoxication Deaths. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology. 2021 Mar 1:42(1):9-11. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000622. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33031124]

Reyes JC, Negrón JL, Colón HM, Padilla AM, Millán MY, Matos TD, Robles RR. The emerging of xylazine as a new drug of abuse and its health consequences among drug users in Puerto Rico. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2012 Jun:89(3):519-26. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9662-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22391983]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGreene SA, Thurmon JC. Xylazine--a review of its pharmacology and use in veterinary medicine. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics. 1988 Dec:11(4):295-313 [PubMed PMID: 3062194]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuiz-Colón K, Chavez-Arias C, Díaz-Alcalá JE, Martínez MA. Xylazine intoxication in humans and its importance as an emerging adulterant in abused drugs: A comprehensive review of the literature. Forensic science international. 2014 Jul:240():1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.03.015. Epub 2014 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 24769343]

Colby ED, McCarthy LE, Borison HL. Emetic action of xylazine on the chemoreceptor trigger zone for vomiting in cats. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics. 1981 Jun:4(2):93-6 [PubMed PMID: 7349332]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, Viner K. Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010-2019. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention. 2021 Aug:27(4):395-398. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043968. Epub 2021 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 33536231]

Gupta R, Holtgrave DR, Ashburn MA. Xylazine - Medical and Public Health Imperatives. The New England journal of medicine. 2023 Jun 15:388(24):2209-2212. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2303120. Epub 2023 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 37099338]

Spadaro A, O'Connor K, Lakamana S, Sarker A, Wightman R, Love JS, Perrone J. Self-reported Xylazine Experiences: A Mixed Methods Study of Reddit Subscribers. medRxiv : the preprint server for health sciences. 2023 Mar 14:():. pii: 2023.03.13.23287215. doi: 10.1101/2023.03.13.23287215. Epub 2023 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 36993695]

Holt AC, Schwope DM, Le K, Schrecker JP, Heltsley R. Widespread Distribution of Xylazine Detected Throughout the United States in Healthcare Patient Samples. Journal of addiction medicine. 2023 Jan 6:():. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001132. Epub 2023 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 36728486]

Rodríguez N, Vargas Vidot J, Panelli J, Colón H, Ritchie B, Yamamura Y. GC-MS confirmation of xylazine (Rompun), a veterinary sedative, in exchanged needles. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2008 Aug 1:96(3):290-3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.005. Epub 2008 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 18472231]

Thangada S, Clinton HA, Ali S, Nunez J, Gill JR, Lawlor RF, Logan SB. Notes from the Field: Xylazine, a Veterinary Tranquilizer, Identified as an Emerging Novel Substance in Drug Overdose Deaths - Connecticut, 2019-2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021 Sep 17:70(37):1303-1304. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a5. Epub 2021 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 34529638]

Kariisa M, Patel P, Smith H, Bitting J. Notes from the Field: Xylazine Detection and Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths - United States, 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2021 Sep 17:70(37):1300-1302. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a4. Epub 2021 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 34529640]

Friedman J, Montero F, Bourgois P, Wahbi R, Dye D, Goodman-Meza D, Shover C. Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2022 Apr 1:233():109380. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. Epub 2022 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 35247724]

Giovannitti JA Jr, Thoms SM, Crawford JJ. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists: a review of current clinical applications. Anesthesia progress. 2015 Spring:62(1):31-9. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-62.1.31. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25849473]

Kaartinen MJ, Cuvelliez S, Brouillard L, Rondenay Y, Kona-Boun JJ, Troncy E. Survey of utilization of medetomidine and atipamezole in private veterinary practice in Quebec in 2002. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. 2007 Jul:48(7):725-30 [PubMed PMID: 17824157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMalayala SV, Papudesi BN, Bobb R, Wimbush A. Xylazine-Induced Skin Ulcers in a Person Who Injects Drugs in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Cureus. 2022 Aug:14(8):e28160. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28160. Epub 2022 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 36148197]

Rose L, Kirven R, Tyler K, Chung C, Korman AM. Xylazine-induced acute skin necrosis in two patients who inject fentanyl. JAAD case reports. 2023 Jun:36():113-115. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.04.010. Epub 2023 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 37288443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVeilleux-Lemieux D, Castel A, Carrier D, Beaudry F, Vachon P. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and xylazine in young and old Sprague-Dawley rats. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science : JAALAS. 2013 Sep:52(5):567-70 [PubMed PMID: 24041212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMittleman RE, Hearn WL, Hime GW. Xylazine toxicity--literature review and report of two cases. Journal of forensic sciences. 1998 Mar:43(2):400-2 [PubMed PMID: 9544551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilva-Torres L, Veléz C, Alvarez L, Zayas B. Xylazine as a drug of abuse and its effects on the generation of reactive species and DNA damage on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of toxicology. 2014:2014():492609. doi: 10.1155/2014/492609. Epub 2014 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 25435874]

Moeller KE, Lee KC, Kissack JC. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2008 Jan:83(1):66-76. doi: 10.4065/83.1.66. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18174009]

Cheung CW, Qiu Q, Choi SW, Moore B, Goucke R, Irwin M. Chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain: a review and comparison of treatment guidelines. Pain physician. 2014 Sep-Oct:17(5):401-14 [PubMed PMID: 25247898]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRaouf M, Bettinger JJ, Fudin J. A Practical Guide to Urine Drug Monitoring. Federal practitioner : for the health care professionals of the VA, DoD, and PHS. 2018 Apr:35(4):38-44 [PubMed PMID: 30766353]

Meyer GM, Maurer HH. Qualitative metabolism assessment and toxicological detection of xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer and drug of abuse, in rat and human urine using GC-MS, LC-MSn, and LC-HR-MSn. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry. 2013 Dec:405(30):9779-89. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7419-7. Epub 2013 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 24141317]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReed MK, Imperato NS, Bowles JM, Salcedo VJ, Guth A, Rising KL. Perspectives of people in Philadelphia who use fentanyl/heroin adulterated with the animal tranquilizer xylazine; Making a case for xylazine test strips. Drug and alcohol dependence reports. 2022 Sep:4():100074. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100074. Epub 2022 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 36846574]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEhrman-Dupre R, Kaigh C, Salzman M, Haroz R, Peterson LK, Schmidt R. Management of Xylazine Withdrawal in a Hospitalized Patient: A Case Report. Journal of addiction medicine. 2022 Sep-Oct 01:16(5):595-598. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000955. Epub 2022 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 35020700]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGallanosa AG, Spyker DA, Shipe JR, Morris DL. Human xylazine overdose: a comparative review with clonidine, phenothiazines, and tricyclic antidepressants. Clinical toxicology. 1981 Jun:18(6):663-78 [PubMed PMID: 6115734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMackintosh C. Potential antidote for Rompun (xylazine) in humans. The New Zealand medical journal. 1985 Aug 28:98(785):714-5 [PubMed PMID: 3863045]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpoerke DG, Hall AH, Grimes MJ, Honea BN 3rd, Rumack BH. Human overdose with the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1986 May:4(3):222-4 [PubMed PMID: 3964361]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGreenberg M, Rama A, Zuba JR. Atipamezole as an emergency treatment for overdose from highly concentrated alpha-2 agonists used in zoo and wildlife anesthesia. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Jan:36(1):136-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.06.054. Epub 2017 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 28751043]

Zheng X, Mi X, Li S, Chen G. Determination of xylazine and 2,6-xylidine in animal tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of food science. 2013 Jun:78(6):T955-9. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12144. Epub 2013 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 23647632]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSakamoto H, Misumi K, Nakama M, Aoki Y. The effects of xylazine on intrauterine pressure, uterine blood flow, maternal and fetal cardiovascular and pulmonary function in pregnant goats. The Journal of veterinary medical science. 1996 Mar:58(3):211-7 [PubMed PMID: 8777227]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence