Introduction

Immune-mediated diseases often involve the oral mucosa, frequently demonstrating the first visible sign of the disease process. Oral mucosal lesions related to immune dysfunction or presumed autoimmune etiologies may be symptomatic, seriously affecting quality of life, and serve as an associated comorbidity in high-risk patient populations. The clinical presentations of the lesions—including recurrent aphthous stomatitis, lichenoid lesions, and related conditions, systemic lupus erythematosus, vesiculobullous disease, erythema multiforme, and benign migratory glossitis—are often nonspecific, subtle, and ever-changing in appearance; typically, they require detailed evaluation of patient histories, histopathologic studies, and multidisciplinary consultation for definitive diagnosis. In otherwise asymptomatic patients, a detailed clinical examination allows an opportunity for early diagnosis and treatment. Patients may find treatments to provide unsatisfactory or inconsistent results but may also be content with simple, noninvasive therapies.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is one of the most common oral ulcerative conditions; it typically presents as 1 of 3 clinical variations: minor, major, and herpetiform (see Image. Aphthous Ulcer). Classification is based on the number of ulcerations, duration, location, frequency of recurrence, and severity.[1] The etiology is unknown but is suggested to be a multifactorial process involving an underlying genetic susceptibility and possible contributing factors, including bacterial or viral microbial entities, topical agents, foods, medications, hormones, stress, nutritional deficiencies, and systemic disease.[2]

Oral Lichen Planus

Oral lichen planus is a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease that can affect the mucosa of the skin, eyes, vagina, and mouth.[1] Systemic disease, local irritants, and drug reactions have also been found to mimic oral lichen planus. The oral lesions noted in oral lichen planus are often identified as oral lichenoid mucositis, which is a histologic inflammatory process that may represent true oral lichen planus or be caused by local irritation (contact reaction) due to dental materials, such as dental amalgam restorations, ingredients in toothpaste, food additives, and systemic medications including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antihypertensives, antimalarials, and antiretrovirals (see Image. Lichenoid Mucositis).[3]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic and progressive autoimmune inflammatory disease characterized by immune complex deposition in various organ systems, resulting in inflammation and impairment.[4][5]

Vesiculobullous Diseases

Vesiculobullous diseases are a group of immune-modulated conditions that often affect the oral cavity; the most discussed vesiculobullous diseases include mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris (see Image. Vesticobullous Disease). These diseases are both B-cell–mediated autoimmune conditions characterized by antibody response toward the structural components of the epithelium, resulting in the formation of vesicles and bullae on the oral mucosa and other mucosal and skin surfaces. Characteristically, mucous membrane pemphigoid demonstrates immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin M, or complement factor 3 autoantibodies against basement membrane components, resulting in complete separation of the mucosa (epidermis) from the submucosa (dermis) and causing subepithelial bullae.[6][7] Pemphigus vulgaris is typically characterized by IgG autoantibodies directed against desmosomes, resulting in loss of cell-to-cell adhesion in the mucosa (epidermis) that can progress to intraepithelial vesicles (see Image. Pemphigus Vulgaris).[8]

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme is a T-cell–mediated abnormal immune response that clinically presents with skin and oral ulcerations and classic targetoid lesions (see Image. Erythema Multiforme).[9] Erythema multiforme is most commonly associated with infectious conditions (herpes simplex virus [HSV], Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Epstein-Barr virus), but an association has also been noted with medications (including NSAIDs, antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarial agents), food, immunizations, radiation, and malignancy.[10][11]

Benign Migratory Glossitis

Benign migratory glossitis, also known as geographic tongue or erythema migrans, is a chronic inflammatory condition typically involving the tongue's dorsal surface (see Image. Benign Migratory Glossitis). The etiology of this condition is unknown but is believed to be an immune-mediated process.[12]

Epidemiology

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is the most common cause of acute recurrent oral mucosal ulcers; it occurs in 1 out of every 5 individuals, with the highest incidence in adolescents and young adults. Recurrence typically decreases with age, and it is unusual for patients over the age of 40 to develop new-onset recurrent aphthous stomatitis.[13]

Oral Lichen Planus

Oral lichen planus is a relatively common disease with an estimated prevalence of 0.22% to 5% worldwide. Like many autoimmune disease processes, this mucocutaneous disease is more prevalent in females than males and commonly presents in the 4th to 8th decade of life.[14]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE affects women more than men (8:1, respectively) and typically presents in individuals in their 4th to 5th decades of life. It has a worldwide prevalence of 12 to 50 cases per 100,000, depending on location and ethnicity. The prevalence of mucosal involvement in SLE patients is debated, with some authors suggesting that oral lesions are present in 9% to 45% of patients with the more common SLE and 3% to 20% in those with cutaneous lupus erythematous.[4]

Vesiculobullous Diseases

Vesiculobullous diseases are rare, with a worldwide incidence estimated between 0.1 to 0.5 per 100,000 person-years for pemphigus vulgaris and 2 per 1,000,000 person-years for mucous membrane pemphigoid. Both diseases are more common in adults in their 5th to 7th decade with no known geographic or racial predilection. Mucous membrane pemphigoid shows a higher incidence in females, whereas pemphigus vulgaris is equally common between the sexes.[15]

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme has an incidence of less than 1% and most frequently affects individuals between their 3rd and 4th decades of life, with a slightly higher male predominance.[16]

Benign Migratory Glossitis

Benign migratory glossitis is relatively common, with a global prevalence of approximately 1% to 2.5%. It most commonly presents in individuals in their 3rd and 4th decades of life, with a slightly higher incidence in women than men.[17]

Histopathology

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Microscopic evaluation of recurrent aphthous stomatitis demonstrates nonspecific mucosal ulceration.[1]

Oral Lichen Planus

Historically, establishing reliable criteria for clinical and histopathologic diagnosis of oral lichen planus has been challenging. Microscopic findings are often in the form of interface mucositis or lichenoid mucositis; these include a band-like, typically chronic (lymphocytic) inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial lamina propria, as well as associated basal-layer degeneration and lymphocytic exocytosis, Civatte bodies, and hyperkeratosis.[3][18]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE shares some similarities with oral lichen planus or lichenoid mucositis, characterized by an interface mucositis pattern with an alternating acanthotic and atrophic spinous layer, hyperkeratosis, and degenerated basal layer. Unlike oral lichen planus , SLE demonstrates positive reactivity to periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) in patchy aggregates near the basal membrane. Additionally, a deeper, perivascular inflammatory infiltrate is often noted.[19]

Vesiculobullous Diseases

Vesiculobullous diseases are diagnosed histologically, often with direct immunofluorescence, and require a perilesional mucosal biopsy. For mucous membrane pemphigoid, immunofluorescence will highlight autoimmune antibodies directed against the basement membrane, causing subepithelial separation.[6] For pemphigus vulgaris, immunofluorescence will demonstrate autoantibodies targeting the intraepithelial desmosomes, causing the separation of basal cells within the mucosa.[8]

Erythema Multiforme

Tissue biopsies of erythema multiforme typically show nonspecific ulceration. They may demonstrate acanthosis and subepithelial separation with perivascular inflammation.[11]

Benign Migratory Glossitis

Benign migratory glossitis shows psoriasiform mucositis during microscopic evaluation. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and elongation of rete ridges are common, along with spongiosis and aggregates of acute inflammatory infiltrate (neutrophils) within the epithelium. These aggregates are termed Munro microabscesses. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate may be seen in the lamina propria.[20]

History and Physical

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: This most frequently presents as single or multiple painful oral ulcerations on the unattached (nonkeratinized) mucosa. A characteristic central ulcerated area of necrosis covered with a yellow-white fibrinopurulent membrane is noted, along with a distinct erythematous halo. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis clinical variations are differentiated by the frequency of recurrence, the size and number of ulcerations, and the rate of healing.

Minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis demonstrates the fewest recurrences, with lesions measuring 3 to 10 mm in diameter that heal in 7 to 14 days without scarring. Major recurrent aphthous stomatitis demonstrates intermediate recurrence rates with lesions measuring 1 to 3 cm in diameter that heal in 2 to 6 weeks with potential scarring. Herpetiform recurrent aphthous stomatitis demonstrates the most frequent recurrences with multiple lesions (up to 100) of 1 to 3 mm diameter that heal in 7 to 10 days.

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis–type ulcers can be related to systemic conditions such as immunosuppression, inflammatory bowel disease, and Celiac disease. Additionally, the presence of skin, genital, and ocular ulcerations may suggest underlying congenital syndromes such as Beçhet's disease, mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage syndrome, and reactive arthritis (Reiter's syndrome).[21][22][23]

Oral Lichen Planus

Oral lichen planus has various oral manifestations and can be categorized as reticular or erosive variants. Reticular lichen planus demonstrates symmetric, asymptomatic, white, and reticular or lace-like lesions on the mucosa (Wickham's striae), most commonly on the buccal mucosa. Erosive lichen planus is characterized by symptomatic oral mucosal ulcerations, often also found on the gingiva (desquamative gingivitis). Purple, polygonal, pruritic papules on the extensor surfaces of the skin classically characterize extraoral presentation of the disease. Nonsystemic lichenoid mucositis and other systemic diseases, such as graft-versus-host disease and SLE, have been found to mimic the clinical presentation of oral lichen planus.[1]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE presents with highly varied clinical findings across numerous organ systems. The oral manifestations are among the first signs to appear and may mimic those of oral lichen planus. Oral ulcers are the most common oral finding (79%), followed by altered salivary flow, oral pigmentation, cutaneous malar rash, cheilitis, glossodynia, fissured tongue, erosion, and hyperkeratosis.[24]

Vesiculobullous Diseases

Vesiculobullous diseases typically present as transitory fluid-filled lesions and ulcerations involving the oral cavity and other mucosal surfaces, including the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and conjunctiva. Flaccid, fragile, intraepithelial vesicles or bullae characterize pemphigus vulgaris. However, patients will often only clinically present with painful ulcers and erosions due to the weak nature of the vesicles and bullae with an intraepithelial splitting pattern. In mucous membrane pemphigoid, the vesicles and bullae are typically found intact, as they are structurally stronger due to the subepithelial splitting pattern and are often associated with desquamative gingivitis.[6]

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme characteristically presents with symptomatic ulceration of oral mucosa and lips with hemorrhagic crusting on the lower lip. This pattern overlaps with signs of other processes such as oral lichen planus, SLE, and graft-versus-host disease. However, lesions on the genital and ocular mucosa are also possible. The classic cutaneous findings of erythematous target-like lesions usually assist in arriving at the correct working diagnosis.[11]

Benign Migratory Glossitis

Benign migratory glossitis typically appears as asymptomatic, well-demarcated patches or zones of atrophic filiform papillae (represented by red erythematous areas) bordered by thin, elevated, yellow/white hyperkeratoses in a scalloped or serpentoid pattern. These patches vary in size and are most commonly associated with the anterior two-thirds of the dorsal surface of the tongue. The erythematous patches are not static and change location and size frequently, sometimes disappearing entirely. Some patients may note sensitivity or a burning sensation to acidic or spicy foods, typically when the lesions are present. The separate process known as burning mouth syndrome may or may not present concurrently with benign migratory glossitis, confounding diagnosis and treatment.[17][25]

Evaluation

Evaluation of oral mucosal lesions involves a thorough physical examination, detailed subjective history, and tissue biopsy if indicated. A bimanual exam with adequate illumination is used to characterize the size, shape, color, texture, and location of the lesion(s). While assessing a patient, the clinician must determine the onset and duration of the lesion, the change in character or size, and the presence, absence, and quality of pain.

A tissue biopsy is often indicated for definitive diagnosis, especially if epithelial dysplasia or a malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, is part of the differential diagnosis. The biopsy may involve traditional fixation in formalin for standard hematoxylin and eosin–stained evaluation or a transport medium such as Michel's, Zeus, or DIF solution for evaluation under direct immunofluorescence. The biopsy procedure is typically conducted on entirely or partially perilesional mucosa, as ulcerated tissue often fails to provide diagnostic specificity. It can be completed by a qualified healthcare provider such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, otolaryngologist, dermatologist, or dentist, and is preferably sent for histopathologic analysis to a pathologist with additional training in the fields of oral and maxillofacial pathology, head and neck pathology, or dermatopathology.

Treatment / Management

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

Patients with mild recurrent aphthous stomatitis often manage symptoms with no treatment or with over-the-counter (OTC) topical anesthetics and medications. For those patients with recurrent minor or herpetiform recurrent aphthous stomatitis not relieved by simple at-home modalities (no treatment or OTC products), topical corticosteroids or in-office application of chemical cautery agents (sulfonated phenolics/sulfuric acid) is the palliative treatment of choice. Frequently utilized modalities include dexamethasone swish-and-spit (5 mg/5 mL) solution, 0.05% augmented betamethasone dipropionate gel, 0.05% fluocinonide gel, or 35%-60% sulfonated phenolics/25%-35% sulfuric acid preparations. Major recurrent aphthous stomatitis often requires more targeted corticosteroid therapy, as the large-scale application of chemical cautery products is often impractical and ill-advised. Local treatment options include triamcinolone acetonide injections, triamcinolone tablets dissolved over lesions, 0.05% clobetasol propionate gel, 0.05% halobetasol propionate ointment, or beclomethasone dipropionate aerosol spray. If these treatments remain ineffective, oral prednisolone swish-and-swallow can be added as a systemic adjunct to therapy. Several other systemic immunomodulatory agents have been used to treat recurrent aphthous stomatitis. However, the use of these agents should be weighted with their corresponding increased risk profile and high cost.[26][27](A1)

Oral Lichen Planus

Reticular lichen planus is often asymptomatic and requires no treatment despite clinically demonstrating classic lace-like Wickham's striate. The lichenoid lesions that mimic reticular oral lichen planus frequently resolve spontaneously upon cessation or removal of the inciting agent, often without any action by the patient or clinician, as the inciting agent may never be identified. Gaining an accurate history of the patient's lesions to elucidate the etiology may be the most crucial aspect of their treatment. When the source of the lesions is not immediately apparent, providing the patient with a list of common sources to avoid (eg, certain dental materials, sodium lauryl sulfate and other additives in toothpaste, and cinnamon products) may be helpful, in combination with close follow-up. In the case of dental amalgam–related reactions, replacement with composite resins are recommended. Likewise, medications should be replaced with agents that achieve similar therapeutic outcomes. In some cases, topical corticosteroids may be required for complete resolution. Erosive lichen planus provides additional treatment challenges. First-line treatment for these lesions continues to be topical corticosteroids with guidelines similar to those discussed for recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Similarly, the use of oral prednisone and topical and systemic immunomodulatory agents as secondary treatment options for refractory disease have been described.[28][29][30][31](A1)

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Treatment of SLE is characterized by general lifestyle modifications and individualized pharmacological therapy based on predominant symptoms. Avoidance of ultraviolet light is recommended to prevent exacerbation/induction of systemic symptoms. Patients with symptomatic SLE may be treated by their rheumatologist with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily (≥80 kg) or 5 mg/kg/day (≤80 kg). Depending on the severity of the disease, nonsteroidal NSAIDs and oral glucocorticoids may be utilized in varying doses. Additional immunomodulatory agents such as mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and anifrolumab may be used in cases of severe disease. These agents are often prescribed by a specialist comfortable with and competent in managing SLE and other autoimmune diseases. As a systemic immunologic disease, treating oral lesions is often a secondary outcome of disease management.[32][33][34](B2)

Vesiculobullous Diseases

Similar to SLE, the treatment of vesiculobullous diseases is focused on the control of systemic disease. Ideal initial management of pemphigus vulgaris and severe mucous membrane pemphigoid involves the use of oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day with intravenous rituximab 1 g every 2 weeks for 2 doses. If rituximab therapy is not possible, the same oral prednisone treatment should be combined with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily or oral azathioprine 1 mg/kg/d with a targeted maintenance dose of 2.5 mg/kg/d. The ultimate goal is symptomatic control and appropriate prednisone and adjunctive therapy tapering. Management of mild mucous membrane pemphigoid involves the use of topical corticosteroids (0.05% clobetasol propionate gel, dexamethasone swish-and-spit (5 mg/5 mL) solution), 0.5 to 1 mL triamcinolone acetonide injections (10 mg/mL), or 0.1% topical tacrolimus ointment. Moderatemucous membrane pemphigoid treatment will often involve the use of oral prednisone 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg/d for up to 6 months, with the addition of the aforementioned adjunctive therapies utilized in severe mucous membrane pemphigoid as needed. It is generally accepted that all patients diagnosed with mucous membrane pemphigoid should be referred to ophthalmology to manage and prevent ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.[35][36][37] (A1)

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme treatment primarily involves removing the inflicting agent and site-specific management. In the instance of medication-induced erythema multiforme, the causative drug should be discontinued. Likewise, infection-associated erythema multiforme is managed via treatment of the related infection. For acute erythema multiforme caused by an HSV infection, the use of antiviral therapy is controversial. The presentation of erythema multiforme symptoms follows the clinical presentation of HSV, potentially making antiviral therapy ineffective. Site-specific management for mild oral lesions involves topical corticosteroids (eg, 0.05% fluocinonide gel). For severe oral lesions, oral prednisone 40 to 60 mg/day tapered over 2 to 4 weeks may be used. Intravenous fluids may be necessary for those patients who become dehydrated due to painful oral lesions. Similar to mucous membrane pemphigoid, the presence of ocular lesions necessitates the involvement of the ophthalmology team.[38]

Benign Migratory Glossitis

Patients should be assured that benign migratory glossitis is a benign process that requires no treatment. For those patients who report symptoms, evidence-based treatment options are limited. However, treatment with topical and systemic antihistamines, topical tacrolimus, and topical corticosteroids have been described. As previously described, sensitivity or burning associated with acidic or spicy foods can be part of the benign migratory glossitis spectrum but also may represent a concurrent glossodynia or burning mouth syndrome; this neuropathic disease may be best evaluated by an orofacial pain specialist.[25][39] (A1)

For all of the aforementioned disease processes, simple management with topical or limited-use medications can typically be conducted by a primary care physician, such as a general dentist or family practitioner. In many cases, the patient has already been referred to a surgical specialist, such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, dermatologist, or otolaryngologist, for evaluation and biopsy. If the surgeon or treating physician is unable to identify or favor an underlying specific disease process related to the immune-mediated oral mucosal lesion or feels uncomfortable treating a complex process with high-level agents, referral to a rheumatologist or other experienced provider is recommended. A multidisciplinary approach is required for many cases. Unfortunately for patients and physicians, some of these underlying diseases are indolent but refractory and may result in patient dissatisfaction with ultimate outcomes. Conversely, basic palliative management and patient education is frequently the only treatment needed, resulting in excellent outcomes.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for immune-mediated diseases involving the oral mucosa may be broad and often overlap with disease processes within the same category

Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis

- HSV

- Vesiculobullous disease

- Oral lichen planus

Lichenoid Lesions and Related Conditions

- Oral lichen planus

- Lichenoid mucositis

- Graft-versus-host disease

Vesiculobullous Lesions

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Mucous membrane pemphigoid

- Oral lichen planus

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Lichenoid mucositis

- Oral lichen planus

- Cutaneous lupus

Erythema Multiforme

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- Vesiculobullous diseases

- Fixed drug reaction

Benign Migratory Glossitis

- Oral candidiasis

- Oral lichen planus

- SLE

Prognosis

The prognosis of oral mucosal lesions is contingent on the type of immunologic disease; however, they typically follow a chronic and relapsing course.[1] Management of these oral lesions revolves around treating signs and symptoms in periods of recurrence and maintaining periods of latency by avoiding the inciting etiology. These diseases are often well managed with the standard of care treatment interventions described above, but over time, they may recur and require escalation of treatment. Over time, particularly if no obvious inciting agent is identified and the disease course becomes less indolent, the more aggressive therapies may cause significant side effects and poor compliance. Some patients may elect to discontinue therapies and/or find them nonsatisfactory. Like many other systemic autoimmune processes, the long-term prognosis varies greatly, with the frequency and intensity of recurrences directly impacting patient satisfaction.

Complications

In general, immune-mediated oral mucosal lesions are self-limiting, and complications are associated with the underlying etiologic autoimmune disease process or side effects from anti-inflammatory medications. In vesiculobullous diseases like pemphigus vulgaris or mucous membrane pemphigoid, diffuse ulcerations of the mucosa and skin can cause scarring and, in severe cases, can cause life-threatening dehydration if left untreated.[6]

One of the more concerning complications is the premalignant potential of certain underlying disease types, particularly ulcerative oral lichen planus. Historically, oral lichen planus has been associated with a low but serious risk of malignant transformation; however, this is controversial due to the lack of reliable documentation proving a direct correlation. Some sources suggest that histologic similarities between a dysplastic leukoplakic lesion with a secondary lichenoid infiltrate and a true transforming lichen planus may be the reason for this historical association (see Image. Erythro-Leukoplakic Buccal Mucosal Lesion). Additionally, lichen planus and squamous cell carcinoma are relatively common, so the possibility of concurrent processes at the same site could be confounding. Furthermore, epithelial dysplasia and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia have variable presentations that may clinically mimic lichenoid lesions. Researchers advocating for the premalignant potential of lichen planus note the increased vulnerability of the chronically inflamed and atrophic epithelium to cancer-causing agents, immune dysregulation, and decreased immune surveillance.[1][3]

Although initial evaluation and treatment are often performed by a primary care physician, such as a general dentist or family practitioner, to whom the patient may initially present or demonstrate an incidental finding, other specialists are typically required for treatment and further management. Inappropriate management, such as simply treating obvious symptomatic oral lesions palliatively without follow-up to evaluate improvement and possible systemic or cutaneous manifestations, may delay the diagnosis of a more impactful systemic autoimmune process. It is critical that primary care physicians, including general dentists, refer patients to a clinical specialist such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, or otolaryngologist when appropriate. An eventual referral to rheumatology is often required for additional work-up if simple anti-inflammatory treatments fail to resolve or control recurrences.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given their immune-mediated etiology, some patients are presumed to be genetically predisposed to these conditions and complete deterrence may not be possible. However, with early detection of disease, proper identification, and treatment including identifying possible external etiologic agents, the patient's symptoms may be well managed. Patients should be educated on possible triggers and external agents and counseled on avoidance of inciting factors through lifestyle modifications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the risk of progressive, relapsing disease and potential malignant transformation, prompt diagnosis of oral mucosal manifestations of immune-mediated disease is critical. Oral lesions that grow rapidly, become fixed, evolve, and display atypical features should be immediately referred to the appropriate healthcare specialist for prompt evaluation, biopsy, and diagnosis. Management of immunologic disease is complex and may require an interprofessional team approach, including the expertise of dentists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, pathologists, otolaryngologists, dermatologists, rheumatologists, immunologists, and pharmacists as well as auxiliary and primary care staff. The interprofessional team–based treatment approach is crucial to patient outcomes and the successful treatment of these diseases.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Erythro-Leukoplakic Buccal Mucosal Lesion. Lesion with central ulcer on an asymptomatic 40-year-old man. The classic presentation of a lichenoid process typically represents either lichenoid mucositis or oral lichen planus. Note radiating Wickham striae.

Contributed by Parth Mewar, DDS, MS from Tacoma, WA

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Vesiculobullous disease. Biopsy confirmed vesiculobullous disease specifically mucous membrane pemphigoid. Note the appearance of radiating white striae and associated ulcer in this 40-year-old woman. The patient reported a multi-year history of worsening oral ulcers, white and red lesions, fluid-filled blisters, and small ocular lesions. Intraoral clinical presentation pictured here overlaps with lichenoid lesions, lichen planus, and other vesiculobullous disease processes.

Contributed by Ryan Kaye, DMD, MS from Bensalem, PA. Obtained with informed consent.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

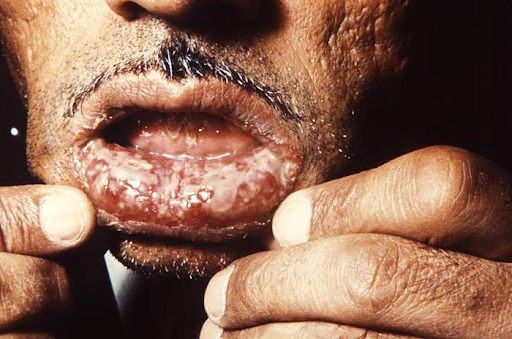

Pemphigus Vulgaris. This image depicts a Tehrani man who was being treated for what was diagnosed as pemphigus vulgaris. He presented with painful, long-standing intraoral lesions that he had for 3 years. The patient also had painful lesions in the perineal region. The intraoral lesions were covered with a grayish-white membrane, which, when peeled away, left a fiery red sore. These lesions were preceded by mucosal eruptions, as were lesions elsewhere on his body.

CDC. Dr J Lieberman and Dr Freideen Farzin, University of Tehran

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Benign Migratory Glossitis. The person had presented to a clinical setting with what was diagnosed as a case of geographic tongue, also known as benign migratory glossitis, consisting of an inflammatory condition of the tongue’s dorsal surface mucous membrane. Benign migratory glossitis may occasionally present on mucosal surfaces other than the dorsal tongue.

CDC. Dr Sellers

References

Fitzpatrick SG, Cohen DM, Clark AN. Ulcerated Lesions of the Oral Mucosa: Clinical and Histologic Review. Head and neck pathology. 2019 Mar:13(1):91-102. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0981-8. Epub 2019 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 30701449]

Shah K, Guarderas J, Krishnaswamy G. Aphthous stomatitis. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2016 Oct:117(4):341-343. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27742082]

Müller S. Oral lichenoid lesions: distinguishing the benign from the deadly. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2017 Jan:30(s1):S54-S67. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.121. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28060366]

Lourenço SV, de Carvalho FR, Boggio P, Sotto MN, Vilela MA, Rivitti EA, Nico MM. Lupus erythematosus: clinical and histopathological study of oral manifestations and immunohistochemical profile of the inflammatory infiltrate. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2007 Jul:34(7):558-64 [PubMed PMID: 17576335]

Saccucci M, Di Carlo G, Bossù M, Giovarruscio F, Salucci A, Polimeni A. Autoimmune Diseases and Their Manifestations on Oral Cavity: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Journal of immunology research. 2018:2018():6061825. doi: 10.1155/2018/6061825. Epub 2018 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 29977929]

Kridin K. Subepidermal autoimmune bullous diseases: overview, epidemiology, and associations. Immunologic research. 2018 Feb:66(1):6-17. doi: 10.1007/s12026-017-8975-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29159697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOhki M, Kikuchi S. Nasal, oral, and pharyngolaryngeal manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris: Endoscopic ororhinolaryngologic examination. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2017 Mar:96(3):120-127 [PubMed PMID: 28346642]

Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, Yamagami J, Zillikens D, Payne AS, Amagai M. Pemphigus. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2017 May 11:3():17026. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.26. Epub 2017 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 28492232]

Maderal AD, Lee Salisbury P 3rd, Jorizzo JL. Desquamative gingivitis: Clinical findings and diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 May:78(5):839-848. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29678378]

Celentano A, Tovaru S, Yap T, Adamo D, Aria M, Mignogna MD. Oral erythema multiforme: trends and clinical findings of a large retrospective European case series. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2015 Dec:120(6):707-16. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.08.010. Epub 2015 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 26455287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeinze A, Tollefson M, Holland KE, Chiu YE. Characteristics of pediatric recurrent erythema multiforme. Pediatric dermatology. 2018 Jan:35(1):97-103. doi: 10.1111/pde.13357. Epub 2017 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 29231254]

Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral diseases. 2006 Jul:12(4):381-6 [PubMed PMID: 16792723]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChattopadhyay A, Shetty KV. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2011 Feb:44(1):79-88, v. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.09.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21093624]

Müller S. Oral manifestations of dermatologic disease: a focus on lichenoid lesions. Head and neck pathology. 2011 Mar:5(1):36-40. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0237-8. Epub 2011 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 21221868]

Bertram F, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D, Schmidt E. Prospective analysis of the incidence of autoimmune bullous disorders in Lower Franconia, Germany. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2009 May:7(5):434-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06976.x. Epub 2009 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 19170813]

Huff JC, Weston WL, Tonnesen MG. Erythema multiforme: a critical review of characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and causes. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1983 Jun:8(6):763-75 [PubMed PMID: 6345608]

Shareef S, Ettefagh L. Geographic Tongue. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32119353]

Cheng YS, Gould A, Kurago Z, Fantasia J, Muller S. Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: a position paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology. 2016 Sep:122(3):332-54. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.05.004. Epub 2016 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 27401683]

Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: issues in diagnosis and treatment. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2009:10(6):365-81. doi: 10.2165/11310780-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19824738]

Picciani BL, Domingos TA, Teixeira-Souza T, Santos Vde C, Gonzaga HF, Cardoso-Oliveira J, Gripp AC, Dias EP, Carneiro S. Geographic tongue and psoriasis: clinical, histopathological, immunohistochemical and genetic correlation - a literature review. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2016 Jul-Aug:91(4):410-21. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164288. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27579734]

Tan CX, Brand HS, de Boer NK, Forouzanfar T. Gastrointestinal diseases and their oro-dental manifestations: Part 1: Crohn's disease. British dental journal. 2016 Dec 16:221(12):794-799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.954. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27982000]

Tan CX, Brand HS, de Boer NK, Forouzanfar T. Gastrointestinal diseases and their oro-dental manifestations: Part 2: Ulcerative colitis. British dental journal. 2017 Jan 13:222(1):53-57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.37. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28084352]

Pak S, Logemann S, Dee C, Fershko A. Breaking the Magic: Mouth and Genital Ulcers with Inflamed Cartilage Syndrome. Cureus. 2017 Oct 4:9(10):e1743. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1743. Epub 2017 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 29218258]

García-Ríos P, Pecci-Lloret MP, Oñate-Sánchez RE. Oral Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Sep 21:19(19):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191911910. Epub 2022 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 36231212]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcNamara KK, Kalmar JR. Erythematous and Vascular Oral Mucosal Lesions: A Clinicopathologic Review of Red Entities. Head and neck pathology. 2019 Mar:13(1):4-15. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01002-8. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30693460]

Liu C, Zhou Z, Liu G, Wang Q, Chen J, Wang L, Zhou Y, Dong G, Xu X, Wang Y, Guo Y, Lin M, Wu L, Du G, Wei C, Zeng X, Wang X, Wu J, Li B, Zhou G, Zhou H. Efficacy and safety of dexamethasone ointment on recurrent aphthous ulceration. The American journal of medicine. 2012 Mar:125(3):292-301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22340928]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLau CB, Smith GP. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A comprehensive review and recommendations on therapeutic options. Dermatologic therapy. 2022 Jun:35(6):e15500. doi: 10.1111/dth.15500. Epub 2022 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 35395126]

Carbone M, Conrotto D, Carrozzo M, Broccoletti R, Gandolfo S, Scully C. Topical corticosteroids in association with miconazole and chlorhexidine in the long-term management of atrophic-erosive oral lichen planus: a placebo-controlled and comparative study between clobetasol and fluocinonide. Oral diseases. 1999 Jan:5(1):44-9 [PubMed PMID: 10218041]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarbone M, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, Gandolfo S. Systemic corticosteroid therapy of oral vesiculoerosive diseases (OVED). An open trial. Minerva stomatologica. 1998 Oct:47(10):479-87 [PubMed PMID: 9866960]

Corrocher G, Di Lorenzo G, Martinelli N, Mansueto P, Biasi D, Nocini PF, Lombardo G, Fior A, Corrocher R, Bambara LM, Gelio S, Pacor ML. Comparative effect of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment and clobetasol 0.05% ointment in patients with oral lichen planus. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2008 Mar:35(3):244-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01191.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18269664]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAl-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan M, Migliorati CA, Axéll T, Bruce AJ, Carpenter W, Eisenberg E, Epstein JB, Holmstrup P, Jontell M, Lozada-Nur F, Nair R, Silverman B, Thongprasom K, Thornhill M, Warnakulasuriya S, van der Waal I. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2007 Mar:103 Suppl():S25.e1-12 [PubMed PMID: 17261375]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLehmann P, Homey B. Clinic and pathophysiology of photosensitivity in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity reviews. 2009 May:8(6):456-61. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.12.012. Epub 2009 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 19167524]

Sisó A, Ramos-Casals M, Bové A, Brito-Zerón P, Soria N, Muñoz S, Testi A, Plaza J, Sentís J, Coca A. Previous antimalarial therapy in patients diagnosed with lupus nephritis: influence on outcomes and survival. Lupus. 2008 Apr:17(4):281-8. doi: 10.1177/0961203307086503. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18413408]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and clinical management. Journal of autoimmunity. 2019 Jan:96():1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.11.001. Epub 2018 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 30448290]

Joly P, Maho-Vaillant M, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hebert V, Houivet E, Calbo S, Caillot F, Golinski ML, Labeille B, Picard-Dahan C, Paul C, Richard MA, Bouaziz JD, Duvert-Lehembre S, Bernard P, Caux F, Alexandre M, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Vabres P, Delaporte E, Quereux G, Dupuy A, Debarbieux S, Avenel-Audran M, D'Incan M, Bedane C, Bénéton N, Jullien D, Dupin N, Misery L, Machet L, Beylot-Barry M, Dereure O, Sassolas B, Vermeulin T, Benichou J, Musette P, French study group on autoimmune bullous skin diseases. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux 3): a prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017 May 20:389(10083):2031-2040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30070-3. Epub 2017 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 28342637]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHarman KE, Brown D, Exton LS, Groves RW, Hampton PJ, Mohd Mustapa MF, Setterfield JF, Yesudian PD. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017. The British journal of dermatology. 2017 Nov:177(5):1170-1201. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15930. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29192996]

Buonavoglia A, Leone P, Dammacco R, Di Lernia G, Petruzzi M, Bonamonte D, Vacca A, Racanelli V, Dammacco F. Pemphigus and mucous membrane pemphigoid: An update from diagnosis to therapy. Autoimmunity reviews. 2019 Apr:18(4):349-358. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.02.005. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30738958]

Soares A, Sokumbi O. Recent Updates in the Treatment of Erythema Multiforme. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2021 Sep 1:57(9):. doi: 10.3390/medicina57090921. Epub 2021 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 34577844]

de Campos WG, Esteves CV, Fernandes LG, Domaneschi C, Júnior CAL. Treatment of symptomatic benign migratory glossitis: a systematic review. Clinical oral investigations. 2018 Sep:22(7):2487-2493. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2553-4. Epub 2018 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 29982968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence