Introduction

Originally described in 1996 by Hotchkiss, the terrible triad of the elbow constitutes a highly unstable form of fracture-dislocation consisting of elbow dislocation with concomitant radial head or neck and coronoid process fractures.[1][2][3]

The historically poor outcomes and high complication rates portend the designation of this injury pattern as “terrible.” Provided its numerous bony and soft tissue structures, the elbow is well known as one of the most stable joints of the body. The complex anatomical structure and higher functional requirements make treating the elbow more difficult.[4]

Owing to those mentioned above, even isolated elbow dislocations without bony fragmentation indicate substantial soft tissue injury with capsular and ligamentous disruption. On the other hand, complex elbow dislocations are defined by an association with fracture(s) of one or more major bony stabilizers. Fracture of the radial head, coronoid process, or olecranon inherently destabilizes the dislocation and nearly always mandates operative intervention to restore functional anatomic alignment and joint stability.[5]

Despite clinical and operative advancements and an increased understanding of pathoanatomy and elbow biomechanics, controversies remain regarding the appropriate treatment algorithm. Standardized surgical protocols and novel algorithmic approaches attempt to improve outcomes for terrible triad patients. Successful evaluation and treatment require detailed knowledge of the functional importance and relationship of each bony and soft tissue component and its contribution to elbow stability.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Approximately 60% of complex dislocations are caused by a fall from standing.[6] Falling on an extended arm that precludes valgus, axial, and posterolateral rotational forces, producing a posterolateral dislocation, is often the mechanism of insult.[1]

The primary terrible triad component of elbow dislocation, subsequent to posterolateral dislocation or lateral collateral ligament disruption, then progresses to involve the medial structures (possibly medial collateral ligament). The lateral collateral ligament injury often occurs as an avulsion from its origin, along with a rupture of extensor musculature from the lateral distal humerus. In conjunction with the elbow dislocation, the radial head and coronoid process pathology vary in fragment size and complexity. The risk of recurrent instability and late arthrosis increases with injury complexity and the number of stabilizers involved.[7]

Epidemiology

Radial head fractures constitute 20 to 30% of all adult elbow fractures.[1] 85% of radial head fractures occur between 30-60 years old, with a mean occurrence at age 45.[8]

Coronoid fractures comprise 10 to 15% of elbow injuries. Although one of the most stable joints in the body, the elbow is the second most commonly dislocated joint. Up to 20% of dislocations are associated with a fracture.[9][6][10]

Pathophysiology

The elbow is comprised of three sub-joints - the humeroradial, humeroulnar, and superior radioulnar joints - further made up of the humerus, radius, ulna, and related capsuloligamentous structures.[11][12]

The radial head is an important restraint to posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) and acts as a secondary valgus stabilizer. In an intact elbow, the radial radiocapitellar articulation contributes minimally to valgus stability; however, in the event of MCL or coronoid injury, the radial head acts as the primary stabilizer to valgus stresses and also prevents elbow subluxation.[10] Radial head fractures may be associated with episodic elbow instability, mechanical block to elbow motion, and injury to the distal radioulnar joint and/or the interosseous membrane (Essex-Lopresti).[13]

As a triangular-shaped protrusion at the anterior facet of the proximal ulna, the coronoid process provides ulnohumeral stability anteriorly and a varus buttress while resisting posterior subluxation.[11]

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) are the main capsuloligamentous stabilizers. The MCL is the primary stabilizer of valgus movements. There are three components of the medial collateral ligament: anterior bundle, posterior bundle, and transverse ligament, of which the robust anterior bundle is most important for stability, in its inherent restraint capabilities to valgus and posteromedial rotatory instability.[11]

Cavaderic studies have revealed that fracture-dislocations of the elbow are most likely to occur between 15 degrees of extension and 30 degrees of flexion, where the MCL is the least effective.[6] The lateral collateral ligament is the primary restraint to posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) and contains four components: lateral ulnar collateral ligament, radial collateral ligament, annular ligament, and accessory (posterior) collateral ligament, of which the lateral ulnar collateral ligament is most important for stability.[11]

The humeroulnar joint is the primary contributor to elbow stability, with its highly constrained 180 degrees of articulation. The anteromedial facet resists varus movements. While muscles crossing the elbow joint contribute dynamically, the osseous and ligamentous structures afford static stability.

In the present topic of the terrible triad, it is important to note that structures of the elbow fail from lateral to medial as the forearm supinates and is loaded, indicating a pathology that sees a disrupted lateral collateral ligament first, prior to proceeding to the anterior capsule injury, and then finally, medial collateral ligament.[6] The previously mentioned predictable pattern of disruption from lateral to anterior/posterior and then medial is commonly referred to as the Horri circle.[14]

History and Physical

In line with all acute traumatic injuries and fractures, specifically high-energy elbow fracture-dislocations, initial evaluation should proceed according to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol.

Concomitant fractures, dislocations, and injuries throughout the ipsilateral extremity have been reported. Distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) tenderness may represent an interosseous ligament disruption and the potential for concurrent Essex-Lopresti injury.[13]

Fracture-dislocations present with significant edema, pain, and visible deformity. In contrast to normal 100-degree arcs of flexion/extension (approximately 30 to 130 degrees) and pronation/supination (50/50 degrees), patients may demonstrate limited elbow or forearm motion, particularly in supination/pronation, following injury.[6][4]

Visible inspection may reveal ecchymosis or edema with tenderness over the lateral elbow; deformity may be possible in the setting of associated dislocation. It is important to evaluate flexion/extension, pronation/supination, and the presence of mechanical elbow blocks. Aspiration of joint hematoma and injection of local anesthesia may aid in mechanical block diagnostics.

A thorough neurovascular exam should be performed prior to proceeding with any form of reduction or extremity manipulation. The ulnar nerve is most vulnerable to injury secondary to its position along the medial humeroulnar joint. Brachial artery injury, although rare, can lead to ischemia and compartment syndrome, which are seen more often in pediatric patients.[15]

Evaluation of elbow stability includes a posterolateral drawer and posterolateral pivot shift tests, and varus/valgus instability stress testing. The DRUJ-specific examination includes palpating over the wrist for tenderness and translation >50% in the sagittal plane. Palpate along the interosseous membrane for tenderness and perform a radial pull test at the time of surgery; if >3 mm translation, there should be a concern for longitudinal forearm instability (Essex-Lopresti).[13] When patients present in a delayed or recurrent fashion, the examiner should thoroughly assess elbow flexion/extension, forearm rotation, pain, and nerve function.

Evaluation

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are necessary, although initial imaging may not fully evaluate the complete extent of complex injuries. Additional shoulder, wrist, and hand imaging should also be obtained to rule out concomitant ipsilateral injuries. Radiographs help evaluate the concentricity of humeroulnar and radiocapitellar joints; specifically, lateral films can assist in diagnosing coronoid fractures. While most injuries can be diagnosed with plain radiographs, a computed tomography (CT) scan is routinely obtained for patients with the terrible triad to identify fracture patterns, comminution, and displacement, which may not be evident on plain radiographs. Reconstructed CT scans are helpful to better understand the injury pattern and further assist with preoperative planning.[16]

CT imaging can also detect coronoid, radial head, or olecranon injuries missed on initial radiographs. 3D reconstructions are useful to determine fracture line propagation. Evaluation of fluoroscopic images under anesthesia is beneficial for intraoperative decision-making. Obtaining radiographs after certain mechanisms may be impractical; thus, in select patient populations, performing an examination under anesthesia while taking the elbow through gentle ROM is advantageous. It is important to note and reinforce that prereduction and post-reduction films should be obtained.[17]

For those patients who have already undergone procedural fixation or present in a delayed fashion, imaging should be individualized to the particular patient and their presenting circumstance, as opposed to proceeding with standardized imaging protocols. Nonstandard views may need to be obtained for stiffened joints that are unable to change position to further assess the integrity and alignment of articulating surfaces. Prior internal fixation or radial head implantation may obscure other joint surfaces and misconstrue alignment. CT or MRI should be obtained in these instances.

Various systems exist to assist in further diagnostics: the Mason, Regan and Morrey, and O’Driscoll Classifications.[18]

Under the Mason Classification for radial head fractures:

- Type I radial head fractures are either nondisplaced or minimally displaced (<2 mm), with no mechanical block to rotation

- Type II characterizes displaced (>2 mm) or angulated fractures, with possible mechanical block to forearm rotation

- Type III involves fracture comminution and displacement with confirmed mechanical block to motion

- Type IV radial head fractures are associated with elbow dislocation[11]

The Regan and Morrey Classification system identifies three types of coronoid fractures:

- Type I involves the coronoid tip

- Type II describes a fracture involving 50% or less of coronoid height

- Type III is determined by a fracture of greater than 50% of coronoid height[11][6]

O’Driscoll Classification system subdivides coronoid injuries based on location and the number of coronoid fragments while recognizing that anteromedial facet fractures are caused by varus posteromedial rotatory forces.[19]

Treatment / Management

Treatment options are united in their goal to reestablish enough stability to permit early ROM.[9][20][21] Reestablishing anatomic alignment of osseous structure(s), followed by restoration of the radial head and radiocapitellar contact, which then proceeds to ligamentous repair, outlines the algorithm for treatment of acute injuries, seen within two weeks post-insult.(A1)

Non-operative management with immobilization in 90 degrees of flexion for 7 to 10 days is indicated when the elbow is sufficiently stable to permit early ROM, the coronoid fracture is small, the radial head fracture does not meet surgical indications, and humeroulnar and radiocapitellar joints have been anatomically reduced. Progressive ROM is routinely instituted following one week of immobilization, with active motion initiated in a resting splint at 90 degrees of pronation, ensuring avoidance of terminal extension, with static progressive extension splinting, followed by strengthening protocols beginning after six weeks.

A terrible triad elbow injury that includes an unstable radial head fracture, type III coronoid fracture, with associated elbow dislocation, is an indication for operative intervention, specifically, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) versus radial head arthroplasty, LCL reconstruction, coronoid ORIF, with possible MCL reconstruction. In the event instability persists after addressing the radial head and LCL complex, the next best step is to proceed with operative MCL reconstruction.

Isolated dislocations should be managed by immediate closed reduction. Conscious sedation employed in the emergency department, ensuring adequate analgesia and relaxation, can be readily performed. Reduction maneuvers involve coronal plane translation, followed by olecranon pressure that pushes the ulna distally. Successful reduction is accompanied by a clunking sound parallel to the trochlea falling into the semilunar notch. The elbow should then be tested for stability by proceeding through a series of ROM exercises. Postreduction X-rays are mandatory to confirm reduction. The elbow should be splinted in 90 degrees of flexion. Early ROM should be encouraged. Splinting should not proceed beyond three weeks, subsequent to the risk of persistent flexion contracture and a possible predisposition to heterotopic ossification.

When surgery is indicated for radial head fractures, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) is usually considered the most appropriate choice. Due to its important role as a stabilizer against valgus stresses, radial head resection in fracture-dislocations may lead to Essex-Lopresti instability and arthrosis. Every effort should be made in an attempt to maintain radial head integrity.[10]

Radial head ORIF is ideal for non-comminuted fractures that involve <40% of the articular surface and demonstrate bony continuity between the radial head and neck. Intra-osseous screws, compression screws, retrograde pinning, or anatomic plates can be utilized for definitive fixation. When placing a plate, it must be positioned posterolaterally in the safe zone, with the forearm in neutral, to minimize the risk of injuring the posterior interosseous nerve. Radial head arthroplasty is recommended for patients with a comminuted/displaced fracture of more than three fragments.

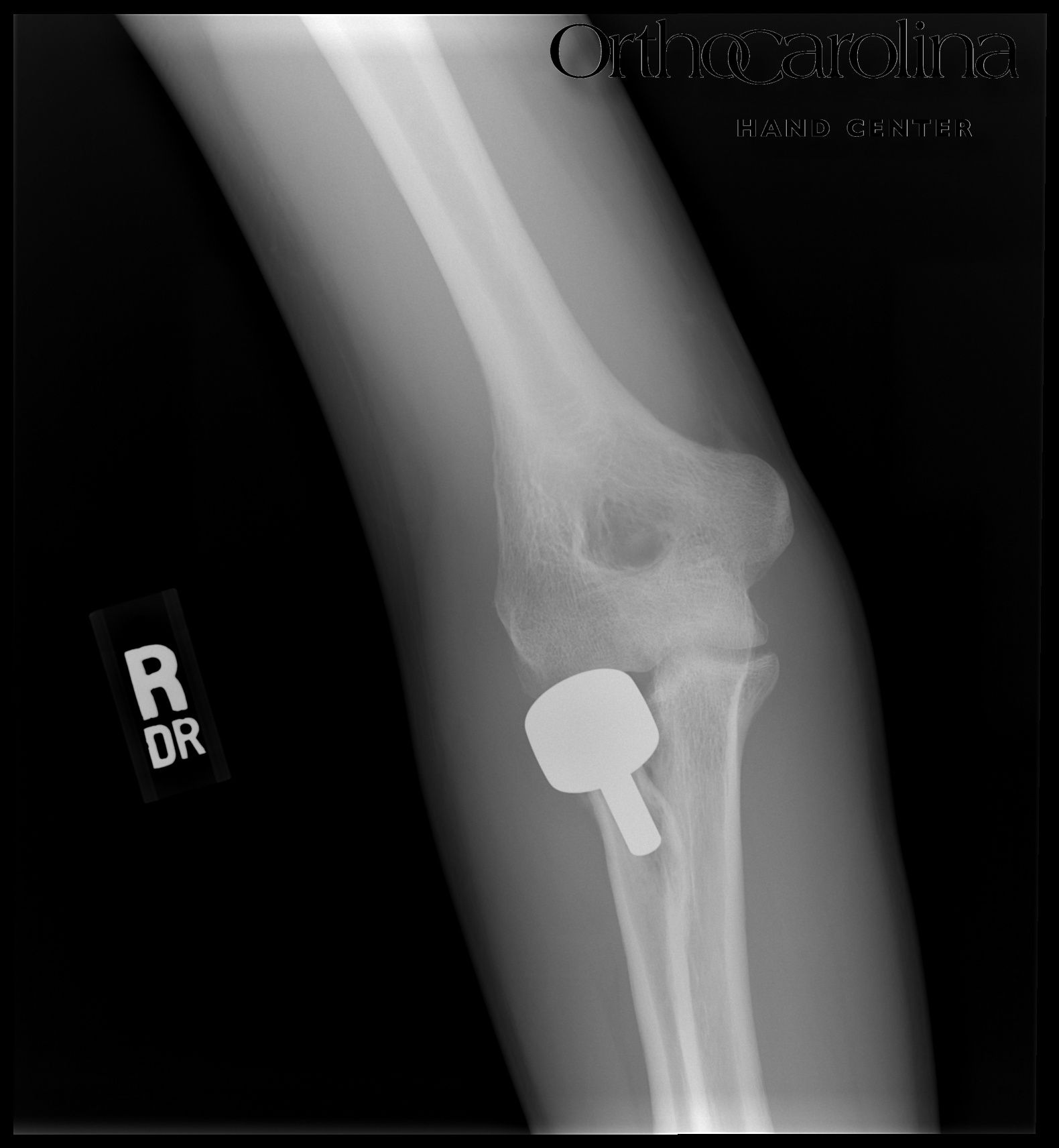

Careful selection of appropriately-sized implants is vital to the success of radial head arthroplasty. A prosthetic head that is too small provides too narrow of a contact region and causes LCL laxity. Too large a head precludes poor congruence and excessive LCL tensioning, leading to postoperative stiffness.[Figures 1,2] Both arthroplasty and non-arthroplasty approaches have demonstrated good outcomes. However, patients undergoing arthroplasty with radial head replacement have demonstrated fewer postoperative complications, with significantly better ROM, than radial head repair.[20] Minus a coronoid fracture, a radial head fracture with concomitant elbow dislocation can be treated with non-operative management. (A1)

Anatomic studies have proven that the elbow cannot be stable in fractures separating >50% of the coronoid process articular surface. Type 3 coronoid fractures are the most challenging type to treat and should be operatively repaired systematically.[10]

Type 1 and 2 fracture treatment depends upon radial head conservation, elbow stability following bony column congruency, and soft tissue reconstruction. If repaired adequately, elbow stability is restored. While the coronoid can be repaired via sutures, anchors, screws, or the “suture lasso” technique, open reduction internal fixation is the most common treatment for terrible triad injuries.[6][10] Coronoid fractures can be repaired via ORIF through the radial head defect laterally.

If a medial approach is used, the median antebrachial cutaneous nerve should be preserved. The coronoid fracture can be exposed between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris; the ulnar nerve should always be visualized and protected. Via landmarks of the lateral epicondyle and radial head/neck under pronation-supination, the lateral approach provides better access to the coronoid process. Bear in mind that a lateral approach approximates the radial nerve throughout the procedure. Postoperatively, active and active-assist ROM therapy is begun after 10-14 days to allow soft tissue healing while reducing pain and edema.

LCL is repaired with the forearm in pronation if the MCL is intact. If MCL is injured, LCL is repaired with the forearm in supination to avoid gapping subsequent to overtightening, with the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion. Postoperatively, it is important to avoid excessive shoulder abduction, which places undue stress on the LCL repair. Prior studies have concluded that stability and adequate elbow function could be operatively restored without repairing the MCL; however, in cases where the elbow remains unstable after fracture fixation and lateral soft tissue (LCL) repair, especially in extension beyond 30 degrees, the MCL should be repaired.[11][10][21]

Inherently, terrible triad injuries following high-energy insults are often accompanied by severe soft tissue injuries, which further prolongs the time to operative treatment, as soft tissue requirements for successful surgical outcomes are met in the interim. Several studies have documented that longer delays to surgery from injury preclude postoperative elbow stiffness. Furthermore, Zhou et al. found that prognostication is optimized when surgical treatment is undergone between 24 hours and 14 days after injury versus delaying until after 14 days.[4]

Lindenhovius et al. demonstrated a better range of motion in patients who underwent surgery within two weeks of injury.[4] Wiigger et al. discovered that every 24-hour delay in surgery following initial injury more than doubles the risk of postoperative elbow stiffness.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

Humeroulnar dislocations are caused by higher-energy mechanisms than simple dislocations and involve greater instability.

In the setting of fracture-dislocation, Hotchkiss's modification of the Mason classification system is as follows: type I fractures are non-operative, type II require fixation, while type III mandate arthroplasty. Dislocations with radial head and coronoid fractures (terrible triad) pose an increasing threat of persistent instability and posttraumatic arthritis. Coronoid fractures can be subclassified by location and size into tip fractures, anteromedial, or basal fractures, as in O'Driscoll and colleagues' nomenclature.[11]

Type I tip fractures involve less than 2 mm of coronoid height, while type II are greater than 2 mm. Anterior and basal fractures are commonly seen with varus posteromedial rotational injuries and olecranon fracture-dislocations. Anteromedial fractures are divided into three categories: type I involving the anteromedial rim, type II of the anteromedial rim and tip, and subtype III of the anteromedial rim and sublime tubercle.[6]

Basal fracture subtype I involve the coronoid body, indicated by at least 50% of the coronoid height, and subtype II is associated with olecranon fractures. It has been previously studied and correlated that elbow stability is proportional to the size and location of the coronoid fracture, the extent of radial head comminution, and the severity of the ligamentous disruption.

The next phase along the continuum of instability and complexity includes disruption of the semilunar notch, dislocation and/or fracture of the radial head, and coronoid fracture. This olecranon fracture-dislocation pathology may exhibit disruption of all osseous stabilizers of the elbow. Coronoid fractures here are generally one large piece (>50% of height). These processes are subdivided into anterior and posterior injuries that, additionally, follow different mechanistic injury patterns.

Transolecranon fracture-dislocation patterns are defined by a complex olecranon or proximal ulnar fracture and dislocation of the forearm, with the maintenance of the proximal radioulnar relationship - a distinct entity in comparison to Monteggia fractures, in which the radioulnar connection is dissociated. These injuries, fortunately, are less common. They are caused by high-energy direct forearm blows and are associated with concomitant ipsilateral elbow injuries in over 80% of cases.[6]

Whether the forearm is dislocated anteriorly or posteriorly is dependent upon the mechanism and directionality of the insult. The elbow is rendered stable following the reduction of proximal ulna anatomy, and outcomes favor a good recovery of forearm rotation. Operative techniques utilizing tension band wiring reliant on an articular surface buttress are frequently complicated, with arthrosis in up to 70% of cases and ulnar nerve dysfunction in almost 25% of patients.[6]

Monteggia fracture-dislocations are generally seen in elderly, frail women with osteopenia/osteoporosis following a low-energy fall directly onto the elbow and are composed of a posterior radial head dislocation, a proximal ulnar fracture, and basal type II coronoid fracture, in addition to humeroulnar instability. In contrast to other varieties of fracture-dislocations, this pathological entity may exhibit persistent instability despite full and complete restoration of bony stabilizers. Posterior Monteggia injuries can be classified as type A fractures involving the coronoid process, type B fractures of the ulnar metaphysis, type C fractures of the ulnar diaphysis, and type D, which are complex, comminuted fractures of the proximal ulna.[15]

Varus posteromedial rotational injuries subsequent to a fall on an outstretched arm with the shoulder in flexion and abduction, subsequently creating a varus posteromedial rotational force, is a less common variant. Coronoid fractures here follow the above-mentioned classification system of type I involving the anteromedial rim, subtype II involving the tip and comminution, or sublime tubercle disruption in type III. This pathology is rarely associated with radial head fracture. It is important to note that the fracture pattern of instability may be very subtle, increasing the chances of missed joint incongruity and thus leading to the rapid development of arthrosis.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Prophylaxis against HO using indomethacin or radiation is unproven for traumatic elbow injuries and may impair fracture healing. However, indomethacin, for short periods, is commonly administered in more complex trauma. Prospective randomized studies suggest radiation therapy should not be used acutely for prophylaxis after elbow trauma because of the increased rate of fracture and/or olecranon osteotomy nonunion.

Authors have investigated the implication of surgical timing regarding operative outcomes. Anneluuk compared an early (1 to 13 days) versus delayed (3 to 13 weeks) group and found that the early group had increased flexion/extension and forearm supination functional recovery in contrast to the delayed group.[3]

Perhaps, the aforementioned phenomenon is subsequent to changes in soft tissues. As hematomas form around the fracture, causing congestion that gradually swells, leading to cellular disruption and potential neurovascular injuries that propagate tissue ischemia and hypoxia, causing more bone and soft tissue necrosis. When the elbow is immobilized for conservative therapy, the hematoma becomes absorptive, the joint capsule contracts, and muscles become atrophic, all worsening joint function. Undergoing early surgery interrupts this chain of inflammatory reactions, leading to joint dysfunction by avoiding joint capsule contracture, muscle atrophy, and fibrous tissue formation.[3]

The earlier the operation is performed, the cleaner soft tissue plains appear, allowing bony landmarks to be identified, easing anatomical reduction and fixation techniques. With expeditious repair, patients can begin performing functional exercises earlier and regain their pre-injury elbow strength and motion.[3]

Prognosis

Although rare, terrible triad injury patterns have historically poor outcomes secondary to persistent instability, stiffness, and arthrosis. A high index of suspicion should be maintained clinically in efforts to expeditiously proceed through a detailed extremity examination, with plans to obtain appropriate imaging studies to achieve a correct diagnosis and, further, proceed with early and adequate treatment.[13]

Complications

Complications following elbow fracture-dislocation include heterotopic ossification (HO), infection, synostosis, arthrofibrosis, recurrent instability, post-traumatic arthritis, stiffness, nonunion, ulnar neuropathy, loosening of implant prompting revision surgery, and symptomatic hardware. Surgically treating terrible triad injuries carries a high risk of complications, with up to a 54.5% reoperation rate, averaging 22 to 30%.[6][22][21]

Successful anatomic reduction of intraarticular fractures is necessary to prevent arthritic changes, although a slight loss of extension is expected. Between 5 and 15% of patients with elbow fractures will experience stiffness following surgery.[4] Arthritis is common after high-energy trauma and is likely a sequela of initial chondral impact and the degree of recurrent elbow instability. Arthroplasty can be considered for younger patients, while total elbow replacement is reserved for the elderly, less active patient population.

A small degree of loss of motion after elbow fracture-dislocation is anticipated. Routinely, patients lose more extension than flexion. The amount of stiffness increases with the energy of initial injury, the amount of heterotopic bone formed, and the delay of motion after repair. For an inadequate range of motion or excessive stiffness, treatment includes splinting, heterotopic bone excision, and capsular release.

Post-traumatic calcium deposition in the collateral ligaments and capsule is relatively common, with previous reports documenting just under a 20% occurrence rate. However, heterotopic ossification (HO) has occurred in up to 43% of operatively treated fracture dislocations.[23][24]

Heterotopic ossification causing near complete ankylosis of the elbow can be seen on radiographic imaging 3 to 4 weeks after injury. The severity and frequency of HO are associated with the magnitude of the injury, soft tissue damage, length of immobilization, neurological injury, infection, delay to surgery, and the presence of associated burns.[24] Heterotopic ossification most commonly occurs either anteriorly, between the capsule and brachialis, or posteriorly, between the capsule and triceps. While no consensus has been reached on an ideal timeline for resection, surgeons generally opt to resect when trabeculae are visualized on imaging, with notable improvement in pronation and supination.

Distraction forces across the fracture secondary to flexion or active extension may lead to nonunion. Failure of internal fixation is most common following radial neck fracture repairs secondary to its inherently poor vascularity that precedes osteonecrosis and nonunion. Although recurrent instability rates are low, the most common etiology is failure to recognize or treat fracture(s) or ligamentous injury. Continued or recurrent instability is more common following type I or II coronoid fractures and is most often evident in the posterolateral position.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative splints are left in place for up to 10 days, depending on stability achieved and concurrent injuries. If both MCL and LCL were repaired, the splint should be positioned in flexion and neutral rotation. Otherwise, the splint may be placed in flexion with forearm pronation to provide stability against posterior subluxation. Some patients may even be cleared to initiate ROM exercises on the first postoperative day, with a majority beginning active ROM within 48 hours to improve functional outcomes. Active and active-assist therapies are employed to permit the recruitment of dynamic muscle stabilizers. Forearm rotation is allowed. Shoulder and wrist exercises are encouraged without restrictions. Patients should be counseled to avoid extension within the terminal 30 degrees of motion for four weeks, as this is the most unstable position.

The terrible triad of elbow injuries is difficult to manage. Even after optimal treatment and compliance with postoperative rehabilitation, rarely is it possible to achieve a normal range of motion. Leandro et al. revealed a mean flexion-extension range of 113 degrees and average flexion contracture of 24 degrees.[10] Pugh et al. reported an average flexion-extension arc of 112 degrees and a mean flexion contracture of 19 degrees. Garrigues et al. documented a mean flexion-extension range of 115 degrees and average flexion contracture of 21 degrees.[11] The aforementioned substantiates ROM limitations as a common finding when treating the terrible triad.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The goal in treating terrible triad injuries is to restore elbow stability and obviate complications. Surgery has been established as the best option for obtaining satisfactory functional results.[2] Although there are variations in surgical technique and operative access approaches, a unified primary objective is to provide sufficient stability to begin early ROM and return of function.

Recent literature reveals Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) and Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) assessments as generally between excellent and good, following operative repair of terrible triad injuries.[2][10] MEPS quantifies pain, mobility, stability, and function, subdividing the results through a scoring system in which 90 to 100 points is considered excellent, 75 to 89 is good, 60 to 74 is fair, and less than 60 denotes a poor outcome.[10]

It may be helpful to utilize the aforementioned assessment tools as surrogates in patient education and perioperative conversations to establish realistic postoperative expectations, provide a comparison of surgical techniques and non-operative therapies, and motivate patients into compliance with postoperative rehabilitation for optimized functional outcomes. Reports document consistently satisfactory surgical outcomes, with results ranging from good to excellent. This parallels previous studies published before 2009. Thus, it appears that current surgical strategies and technology have maintained the proportion of patients experiencing positive outcomes.[22]

Despite a majority of operative patients demonstrating good to excellent results, the significance of postoperative complications is not to be underplayed. Refinement of management strategies will hopefully continue to mitigate the number of patients who experience fair or poor outcomes and/or develop operative sequelae.[22]

Pearls and Other Issues

Widely acknowledged data has been published on the algorithmic approach to optimizing the management of terrible triad injuries, depending on the degree and pattern of presentation.

One such suggestion for diagnostics and treatment was published by Rodriguez-Martin et al. They noted CT with 3D reconstructions could help determine the type of injury. Furthermore, prior to surgery, all equipment should be prepared. They advised a posterior skin incision that permits access to the medial and lateral aspects of the elbow with recommendations to perform anterior ulnar nerve transposition to prevent ulnar nerve dysfunction postoperatively. Rodriguez-Martin et al. discussed repairing structures from deep to superficial, from the coronoid process and radial head to the lateral collateral ligament. They suggested making all attempts at preserving the radial head before opting for arthroplasty.

Upon intraoperative stability examination, if the elbow dislocated in 30 to 45 degrees of extension, they advised repairing the medial collateral ligament; a dynamic external fixator should be applied if instability persists beyond MCL repair. Careful to avoid varus stress during early motion; light movement should be initiated within the first few days following surgery. If the aforementioned protocol was followed, they documented functional elbow results with average flexion of 110 degrees.[11]

Similarly, Pugh et al. discovered the LCL complex must be repaired in all cases, and furthermore, noted radial head fractures should be treated functionally if minimally displaced or fixed, while replacement with an implant was advised if comminution was present. Repair the anterior column by anterior capsule suture or coronoid process fixation. Pugh et al. also mentioned hinged external fixators versus discussions regarding repair of MCL should instability persist, with the greatest consideration to hinged external protection as it allows quicker articular mobilization.[13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The complex anatomical structure, intricate interrelationships, and higher functional requirements of the elbow and its key stabilizers have made managing terrible triad injuries more difficult, with well-documented postoperative complications. Although the literature reveals differences in surgical techniques and approaches to involved structures, across time, surgery has been deemed the optimal option for achieving quality functional outcomes.[2]

Management of these injuries requires an interprofessional healthcare team that includes family clinicians, orthopedic specialists, orthopedic/surgical nurses, and physical therapists, utilizing open communication channels and accurate, updated record-keeping.

As surgical techniques have evolved, open reduction internal fixation of the coronoid process, radial head fixation or arthroplasty, and repair of the lateral collateral ligament complex are still associated with complications.[3]

This activity provides the tools necessary to appropriately examine, evaluate, diagnose, and treat terrible triad injuries operatively while encouraging close postoperative monitoring and adherence to therapy regimens to optimize surgical outcomes and decrease the risk of complications.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Galbiatti JA,Cardoso FL,Ferro JAS,Godoy RCG,Belluci SOB,Palacio EP, Terrible triad of the elbow: evaluation of surgical treatment. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2018 Jul-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 30027079]

Ikemoto RY,Murachovsky J,Bueno RS,Nascimento LGP,Carmargo AB,Corrêa VE, TERRIBLE TRIAD OF THE ELBOW: FUNCTIONAL RESULTS OF SURGICAL TREATMENT. Acta ortopedica brasileira. 2017 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 29375261]

Zhou C,Lin J,Xu J,Lin R,Chen K,Sun S,Kong J,Shui X, Does Timing of Surgery Affect Treatment of the Terrible Triad of the Elbow? Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2018 Jul 9; [PubMed PMID: 29985910]

He X,Fen Q,Yang J,Lei Y,Heng L,Zhang K, Risk Factors of Elbow Stiffness After Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Terrible Triad of the Elbow Joint. Orthopaedic surgery. 2021 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 33619861]

Ohl X, Siboni R. Surgical treatment of terrible triad of the elbow. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2021 Feb:107(1S):102784. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2020.102784. Epub 2021 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 33333276]

Jones ADR,Jordan RW, Complex Elbow Dislocations and the [PubMed PMID: 29290879]

Adams JE, Elbow Instability: Evaluation and Treatment. Hand clinics. 2020 Nov [PubMed PMID: 33040961]

Kovar FM,Jaindl M,Thalhammer G,Rupert S,Platzer P,Endler G,Vielgut I,Kutscha-Lissberg F, Incidence and analysis of radial head and neck fractures. World journal of orthopedics. 2013 Apr 18; [PubMed PMID: 23610756]

Papatheodorou LK,Rubright JH,Heim KA,Weiser RW,Sotereanos DG, Terrible triad injuries of the elbow: does the coronoid always need to be fixed? Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2014 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 24474322]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGomide LC,Campos Dde O,Ribeiro de Sá JM,Pamfílio de Sousa MR,do Carmo TC,Brandão Andrada F, TERRIBLE TRIAD OF THE ELBOW: EVALUATION OF SURGICAL TREATMENT. Revista brasileira de ortopedia. 2011 Jul-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 27027024]

Xiao K,Zhang J,Li T,Dong YL,Weng XS, Anatomy, definition, and treatment of the [PubMed PMID: 25708030]

Liman MNP,Avva U,Ashurst JV,Butarbutar JC, Elbow Trauma StatPearls. 2022 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 31194385]

Ramzi Z,Juanos Cabans J,Jennart H, Terrible triad of the elbow with an ipsilateral Essex-Lopresti injury: case report. Journal of surgical case reports. 2020 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 32577203]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Klerk HH,Oosterhoff JHF,Schoolmeesters B,Nieboer P,Eygendaal D,Jaarsma RL,IJpma FFA,van den Bekerom MPJ,Doornberg JN,Traumaplatform 3D Consortium, Recognition of the pattern of complex fractures of the elbow using 3D-printed models. The bone & joint journal. 2023 Jan [PubMed PMID: 36587260]

Gonzalez LJ,Shields CN,Leucht P,Konda SR,Egol KA, Fracture-Dislocations of the Elbow: A Comparison of Monteggia and Terrible Triad Fracture Patterns. Orthopedics. 2022 Dec 2; [PubMed PMID: 36476213]

Ozdag Y,Luciani AM,Delma S,Baylor JL,Foster BK,Grandizio LC, Learning Curve Associated With Operative Treatment of Terrible Triad Elbow Fracture Dislocations. Cureus. 2022 Jul [PubMed PMID: 36039230]

Bozon O,Chrosciany S,Loisel M,Dellestable A,Gubbiotti L,Dumartinet-Gibaud R,Obrecht E,Tibbo M,Sos C,Laumonerie P, Terrible triad injury of the elbow: a historical perspective. International orthopaedics. 2022 Oct [PubMed PMID: 35725951]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLampaert S,Herregodts J,De Wilde L,Van Tongel A, Radial head fractures: a quantitative analysis. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2022 Jun [PubMed PMID: 36001847]

Shukla DR,Fitzsimmons JS,An KN,O'Driscoll SW, Effect of radial head malunion on radiocapitellar stability. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2012 Jun [PubMed PMID: 22521392]

Chen H,Shao Y,Li S, Replacement or repair of terrible triad of the elbow: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2019 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 30732120]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim BS,Kim DH,Byun SH,Cho CH, Does the Coronoid Always Need to Be Fixed in Terrible Triad Injuries of the Elbow? Mid-Term Postoperative Outcomes Following a Standardized Protocol. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020 Oct 29; [PubMed PMID: 33138199]

Chen HW,Liu GD,Wu LJ, Complications of treating terrible triad injury of the elbow: a systematic review. PloS one. 2014; [PubMed PMID: 24832627]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShukla DR,Pillai G,McAnany S,Hausman M,Parsons BO, Heterotopic ossification formation after fracture-dislocations of the elbow. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2015 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 25601384]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTangtiphaiboontana J,Agel J,Beingessner D,Hébert-Davies J, Prolonged dislocation and delay to surgery are associated with higher rates of heterotopic ossification in operatively treated terrible triad injuries. JSES international. 2020 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 32490408]