Introduction

Congenital lacrimal fistula is an uncommon developmental condition consisting of an accessory or anlage canaliculi between the lacrimal system and the skin. In some cases, the course of such abnormal ducts may be blinded and not in communication with the skin, which may render the clinical presentation occult.[1] Congenital lacrimal fistulae classification is based on the origin point of its tract, which may derive from the common canaliculus, the lacrimal sac, or the nasolacrimal duct.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

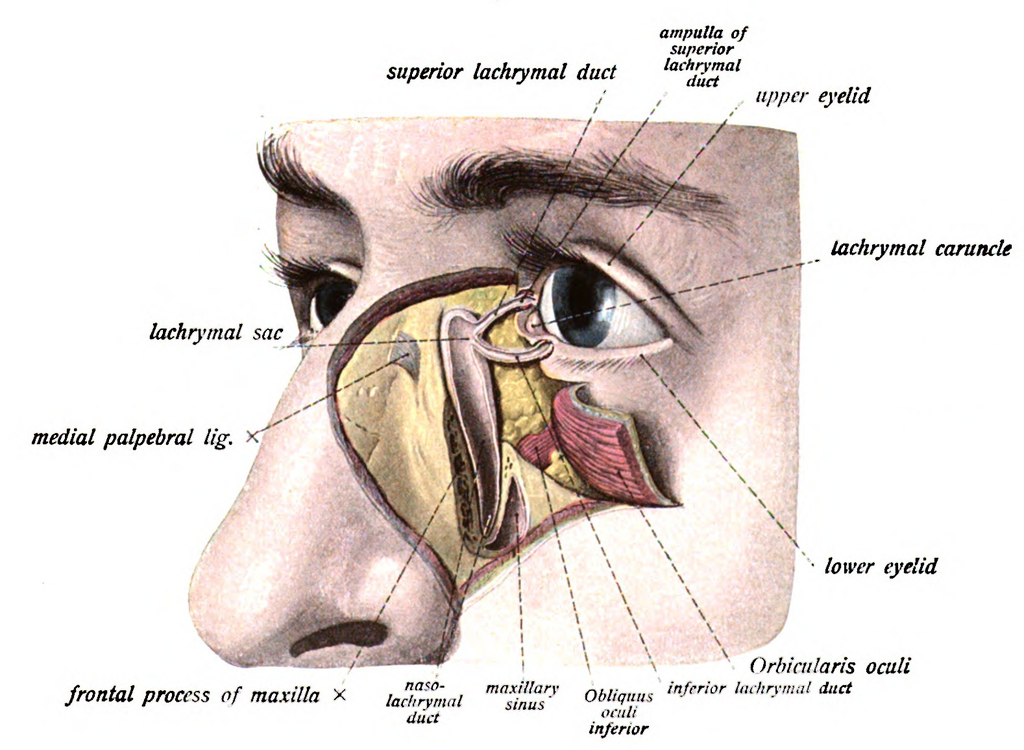

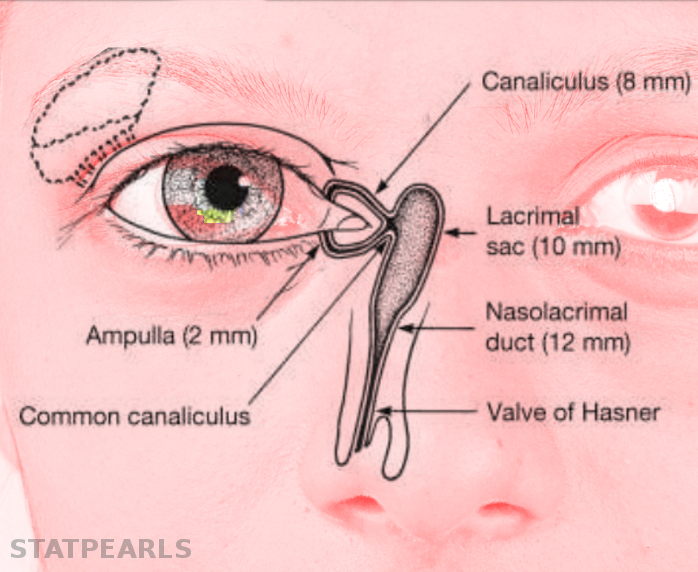

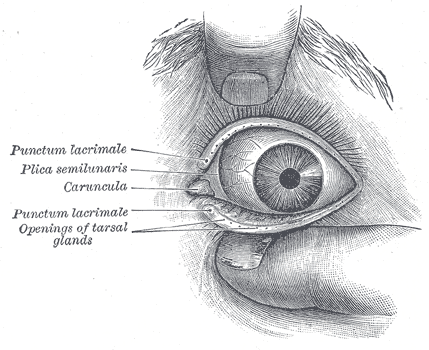

The normal adult anatomy of the lacrimal apparatus includes the puncta lacrimalia, lacrimal ducts, nasolacrimal ducts, sac, and lacrimal glands (see Image. Lacrimal Glands). To understand the pathogenesis of congenital lacrimal fistula, it is necessary to refer to the embryology of the lacrimal system (see Image. The Lacrimal Duct System).

The nasolacrimal ducts originate from an ectodermal thickening around the naso-optic fissure in the early 32-day-old embryo. Canalization begins in the 60-day-old embryo, progressing in a caudal direction. Puncta lacrimalia can be found in the seventh fetal month. At birth, only 30% or less of infants have a patent distal nasolacrimal duct (see Image. Nasolacrimal Duct Opening).[3]

Many hypotheses have been formulated in this developmental process to elucidate the etiopathogenesis of congenital lacrimal fistulae. Some authors have proposed that the fistula derives from excessive growth of the external wall of the nasolacrimal duct, an abnormal closure of the embryonic fissure, and amniotic bands. A phlogistic process may be involved in the formation of acquired fistulae, including purulent dacryocystitis.

Other authors have pointed out that the fistula may originate from a failure in the involution process of lacrimal anlage with a possible aberrant canalization of this cord of cells. Studies have emphasized the role of a dysfunctional fusion of surface ectoderm after the invagination of the ectodermal thickening. All these hypotheses converge on the assumption that anlage ducts persist when lacrimal duct cells fail to involute and continue to canalize in abnormal sites.[4]

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence of congenital lacrimal fistulae is 1 in every 2000 births without any sex predominance; however, these data might be altered by a referral bias, with a possible underestimation.[5] Congenital lacrimal fistulae may be inherited with both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive mechanisms and within complex multifactorial syndromes. Congenital lacrimal fistulae do not seem to exhibit any ethnic predilection. A more evident tendency to bilaterality is present for cases arising within syndromes.[6]

Pathophysiology

In a normal nasolacrimal system, the lacrimal sac is connected to the nasolacrimal duct, which opens into the inferior meatus of the nasal cavity. However, in a congenital lacrimal fistula, there is an abnormal connection between the lacrimal sac and the skin surface near the eye.

The pathophysiology of congenital lacrimal fistula involves the failure of the nasolacrimal system to form properly during embryonic development. This can occur due to a genetic mutation or a disruption in the normal developmental process. As a result, the lacrimal sac may not form properly, or the nasolacrimal duct may not connect properly to the nasal cavity.[7]

The abnormal connection between the lacrimal sac and the skin surface allows tears to drain onto the skin surface instead of through the nasolacrimal duct into the nasal cavity. This can result in recurrent infections, inflammation of the area around the eye, and a blockage in the normal drainage of tears from the eye.

In some cases, the congenital lacrimal fistula may be associated with other congenital anomalies, such as cleft lip and palate, which may also affect the formation of the nasolacrimal system. The pathophysiology of congenital lacrimal fistula involves an abnormal connection between the lacrimal sac and the skin surface near the eye, resulting from a failure of the nasolacrimal system to form properly during embryonic development.

Histopathology

Limited literature reports a histopathological correlation between anlage ducts and congenital lacrimal fistulae. The most common finding in numerous studies is a hypertrophic squamous epithelium lining. Occasionally, translational epithelium and granulation tissue have been reported.[8]

Anecdotal reports have reported a columnar epithelium with intervening goblet cells. Subepithelial layers are generally affected by a chronic inflammatory process with infiltration or fibrosis. The epithelium lining with the lacrimal sac generally transforms into cuboidal cells.[9]

History and Physical

The typical site of presentation is inferior and nasal to the medial canthus, with the majority being unilateral. The surrounding skin usually shows redness and tenderness, with mucous or purulent secretion. In the most frequent scenario, congenital lacrimal fistulae do not cause any symptoms and are frequently missed because of the narrow orifice. In contrast, symptomatic cases may present with epiphora or mucous secretion from the fistula or the eye, especially with a concomitant nasolacrimal duct obstruction, with possible subsequent dacryocystitis.[10]

Blepharitis may develop due to chronic inflammation, leading to redness and swelling of the eyelid. Most patients with epiphora tend to have symptoms since birth, although a minor percentage of patients refer to late-onset symptomatology associated with intermittent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The palpatory sensation of fullness might signify a concomitant mucocele developing within the lacrimal sac.[11][12]

Although the clinical examination remains the main stage of the diagnostic approach, it has limits in that many asymptomatic fistulae, especially if noncommunicating with the external skin, are sometimes not diagnosed. A helpful finding in children is that continuous tearing may be observed from the abnormal site when the child cries. Irrigation of the lacrimal system using a salt solution with fluorescein can enhance the visualization of any skin ostium and is also used to check if the nasolacrimal duct is patent.

Another effective aid is the Valsalva maneuver, which may emphasize the discharge of purulent secretion from the fistula orifice. Other abnormalities that every clinician should be aware of include complete or partial lacrimal agenesis, incomplete punctal canalization with a nonpatent drainage system, duplication of canalicula, obstruction of nasolacrimal ducts, and accessory puncta. Several studies have reported a higher frequency of hypertelorism and strabismus in such patients, especially in syndromic cases.

Notably, a peculiar diagnostic finding can be found during the clinical examination in cases with congenital lacrimal fistulae associated with craniofacial cleft syndromes, such as Goldenhar syndrome or CHARGE (coloboma, heart disease, atresia of the choanae, retarded growth and mental development, genital anomalies, and ear malformations and hearing loss) syndrome.[9]

Evaluation

The most common methods of diagnostic investigation include probing, irrigation, and washing of the lacrimal system and radiological methods with dacryocystography or nuclear scintigraphy. At first presentation, gentle probing of the fistula orifice is performed in an office setting, with subsequent irrigation. The fluorescein dye disappearance test may be used in children, which would generally be uncompliant to probing and irrigation.

In an uncommon clinical setting, as described by several studies, more advanced techniques have been used, including dacryocystoendoscopy, CT with contrast media injected within the lacrimal system, and casting with polyvinyl siloxane. The latter method is quite uncommon, but according to some reports, it may help create 3-dimensional models of the lacrimal system. In some cases, the dacryocystoendoscope aids in visualizing the normal lacrimal anatomy and positioning a silicone drainage tube, thus facilitating eventual fistula excision.[8][13][14] In some reports, methylene blue has been suggested to trace the fistula's path, especially during surgery.[15][16]

Treatment / Management

Conservative treatment is preferred for asymptomatic fistulae, especially when not associated with nasolacrimal duct obstruction.[17] Regarding invasive treatments, the literature reports techniques such as nasolacrimal duct probing, cautery ablation of the external ostium, and surgical excision of the fistula with or without intervening dacryocystorhinostomy. However, there are some controversies concerning the efficacy of dacryocystorhinostomy. Currently, the use of cautery has become more cautious and less popular due to its unsatisfactory success rate and tendency to relapse. Moreover, before performing the fistula excision, it is important to assess the patency of the proper lacrimal system to avoid the risk of postprocedural epiphora and dacryocystitis.[2]

Probing the nasolacrimal duct is recommended when there is a concomitant obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct. Procedures such as simple probing and cauterization may be highly risky, especially if the fistula takes origin from the common lacrimal canaliculus, with the persistence of epiphora of variable degrees owing to the damage to underlying lacrimal ducts.[18]

The fistulectomy procedure can be performed in association or not with dacryocystorhinostomy. When the fistulous tract is excised externally, it is considered a closed fistula excision, whereas, in association with dacryocystorhinostomy, it is regarded as an open excision.[19]

Dacryocystorhinostomy was initially described based on an external approach. The advantage of this technique is that it allows the complete excision of the fistulous tract and optimal visualization of the internal ostium. Moreover, any nasolacrimal duct obstructions can be managed by bypassing the duct. Several studies have recommended external dacryocystorhinostomy, fistula excision, and canalicular intubation to manage symptomatic fistulae.

A modification to external dacryocystorhinostomy, less invasive, is the endoscopic technique, in which there is the creation of a bone window on the medial wall of the lacrimal socket marsupialization of the lacrimal sac in the middle meatus. This technique improves the visualization of the internal ostium, more radical removal of the fistulous tract, and avoids the creation of an unaesthetic scar on the medial canthal region.[20][21](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis should include the evaluation of acquired lacrimal sac fistulae, which tend to occur after the spontaneous drainage of a lacrimal abscess with a history of trauma, such as a naso-orbital-ethmoidal centrofacial fracture. Other conditions may include anatomical abnormalities of the lacrimal apparatus, such as congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and mucoceles, which may cause chronic epiphora, mimicking a congenital lacrimal fistula (see Image. Causes of Epiphora).[22]

Clinicians should differentiate isolated lacrimal fistulae from those associated with Down syndrome, VACTERL syndrome (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula or atresia, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities), clefting syndromes such as ectrodactyly–ectodermal dysplasia–cleft syndrome, and consider coexistence with CHARGE syndrome.[23][24][25][26][27]

Prognosis

According to the most extensive series, recurrence of the fistulous tract is reported at an 11% rate. However, the exact calculation is difficult to perform owing to a heterogeneous origin. In addition, the prognosis for patients with congenital lacrimal fistula generally depends on the severity and location of the fistula. In most cases, the fistula is located near the punctum in the inferior or medial aspect of the eye. If the condition is left untreated, patients may experience recurrent infections, chronic tearing, and even vision loss.

Complications

In general, recurrence is the most severe and tedious complication; others include infection with subsequent dacryocystitis, unfavorable cosmesis, bleeding, and damage to eyelid structures. However, by systematically analyzing potential complications arising when a congenital lacrimal fistula is present, it is possible to include:

-

Recurrent infections: The abnormal connection between the lacrimal sac and the skin surface can allow bacteria to enter the lacrimal sac, leading to recurrent infections. This can cause symptoms such as redness, swelling, discharge, and pain.

-

Chronic inflammation: The presence of an abnormal connection can lead to chronic inflammation in the area around the eye. This can cause discomfort, pain, and swelling.

-

Tear duct obstruction: The presence of a fistula can cause a blockage in the normal drainage of tears from the eye, leading to watery eyes, blurred vision, and an increased risk of eye infections.

-

Cosmetic concerns: The presence of a visible fistula near the eye can be a cosmetic concern, particularly for children. This can cause social anxiety, low self-esteem, and other emotional issues.

-

Delayed speech: The presence of a congenital lacrimal fistula, in rare cases, can lead to delayed speech development in infants. This is thought to be caused by the abnormal connection affecting the muscles and nerves around the mouth.

Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital lacrimal fistula are essential to prevent these complications. Treatment usually involves surgical correction to close the fistula and restore normal drainage of tears from the eye. With prompt and appropriate treatment, most children with congenital lacrimal fistula can have a good outcome and avoid long-term complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated to promptly seek consultation if they experience persistent tearing, sudden infection around the medial canthal area, or symptoms suggestive of dacryocystitis, particularly in pediatric cases. Reporting bias in incomplete literature data underscore the prevalence of undiagnosed cases and highlights the importance of early medical attention.[28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaboration among pediatricians, general practitioners, including mid-level practitioners, and ophthalmology specialists is crucial for early detection of congenital lacrimal fistula cases. Surgical intervention may involve additional professionals such as maxillofacial and ear, nose, and throat surgeons, particularly for dacryocystorhinostomy. Enhanced interprofessional communication and coordination, especially for pediatric or complex syndromic cases, are essential for optimal patient management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lacrimal Glands. The front of the left eye with separated eyelids displays the medial canthus, punctum lacrimalia, plica semilunaris, caruncula, and openings of tarsal glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Causes of Epiphora. The conditions that can cause epiphora include herpes zoster with keratitis (A), lacrimal mucocele (B), corneal calcific keratopathy (C), floppy eyelid syndrome (D), kissing puncta syndrome (E), and pemphigoid disease with trichiasis and obliteration of puncta (F).

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

References

Chaung JQ, Sundar G, Ali MJ. Congenital lacrimal fistula: A major review. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2016 Aug:35(4):212-20. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2016.1176052. Epub 2016 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 27191932]

Choi YM, Jang Y, Kim N, Choung HK, Khwarg SI. The effect of lacrimal drainage abnormality on the surgical outcomes of congenital lacrimal fistula and vice versa. European journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Jan:32(1):108-114. doi: 10.1177/1120672121994721. Epub 2021 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 33579164]

Moscato EE, Kelly JP, Weiss A. Developmental anatomy of the nasolacrimal duct: implications for congenital obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2010 Dec:117(12):2430-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.030. Epub 2010 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 20656354]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlaboudi A, Al-Shaikh O, Fatani D, Alsuhaibani AH. Acute dacryocystitis in pediatric patients and frequency of nasolacrimal duct patency. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2021 Feb:40(1):18-23. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1717548. Epub 2020 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 31994430]

Senthil S, Ali MJ, Chary R, Mandal AK. Co-existing lacrimal drainage anomalies in eyes with congenital Glaucoma. European journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Sep:32(5):2683-2687. doi: 10.1177/11206721211073433. Epub 2022 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 35018871]

Bothra N, Ali MJ. Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction Update Study (CUP Study): Paper 4-Infantile Acute Dacryocystitis (InAD)-Presentation, Management, and Outcomes. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2022 May-Jun 01:38(3):270-273. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002077. Epub 2021 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 34652315]

Zhang HY, Zhang CY, Wang F, Tao H, Tian YP, Zhou XB, Bai F, Wang P, Cui JY, Zhang MJ, Wang LH. Identification of a novel mutation in the FGF10 gene in a Chinese family with obvious congenital lacrimal duct dysplasia in lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital syndrome. International journal of ophthalmology. 2023:16(4):499-504. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2023.04.02. Epub 2023 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 37077496]

Kono S, Lee PAL, Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y. Dacryoendoscopic examination for location of internal orifice of congenital lacrimal fistula: A case series. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Dec:139():110408. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110408. Epub 2020 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 33017665]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceXu Y, Tao H, Wang P, Wang F. [A preliminary study on the clinical features of congenital lacrimal fistula]. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chinese journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep 11:56(9):688-692. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112142-20191008-00502. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32907302]

Missner SC, Kauffman CL. Congenital lacrimal sac fistula: a case report and review. Cutis. 2001 Feb:67(2):121-3 [PubMed PMID: 11236221]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJoos ZP, Sullivan TJ. Congenital lacrimal fistula presenting in adulthood: A case series. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2019 Sep:47(7):949-952. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13555. Epub 2019 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 31077559]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGhosh D, Saha S, Basu SK. Bilateral congenital lacrimal fistulas in an adult as part of ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome: A rare anomaly. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Oct:63(10):800-3. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.171524. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26655010]

Ding J, Sun H, Li D. Persistent pediatric primary canaliculitis associated with congenital lacrimal fistula. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Oct:52(5):e161-e163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2017.03.014. Epub 2017 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 28985821]

Ali MJ. Three-dimensional CT-DCG characterization of congenital lacrimal fistula. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2022 Dec 30:():1. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2022.2157017. Epub 2022 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 36583396]

Anderson SR, Wesley RE. CT scan of cutaneous lacrimal (anlage) fistula. Ophthalmic surgery. 1988 Mar:19(3):202-3 [PubMed PMID: 3353086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhatnagar A, Eckstein LA, Douglas RS, Goldberg RA. Congenital lacrimal sac fistula: intraoperative visualization by polyvinyl siloxane cast. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 Mar-Apr:24(2):158-60. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31816409fc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18356730]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta Y, Bajaj MS. Congenital Common Canalicular Lacrimal Fistula in an Asymptomatic Patient. JAMA ophthalmology. 2023 Jan 1:141(1):e224943. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4943. Epub 2023 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 36656295]

Ali MJ, Bothra N. Radiofrequency-assisted endofistulectomy for a recurrent congenital lacrimal fistula. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2022 Dec:41(6):818-819. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.1874426. Epub 2021 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 33467960]

Bothra N, Naik MN, Ali MJ. Outcomes in pediatric powered endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: a single-center experience. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Apr:38(2):107-111. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2018.1477808. Epub 2018 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 29787339]

Bothra N, Ali MJ. Radiofrequency-Assisted Endofistulectomy: Treating Coexisting Lacrimal Fistulae During Endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2020 Nov/Dec:36(6):610-612. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001698. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32427729]

Al-Salem K, Gibson A, Dolman PJ. Management of congenital lacrimal (anlage) fistula. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Oct:98(10):1435-6. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304854. Epub 2014 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 24831722]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceElmann S, Hanson SA, Bunce CN, Shinder R. Ectrodactyly ectodermal dysplasia clefting (EEC) syndrome: a rare cause of congenital lacrimal anomalies. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Mar-Apr:31(2):e35-7. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24801258]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOnaran Z, Yimazbaş P, Ornek K. Bilateral punctum atresia and lacrimal sac fistula in a child with CHARGE syndrome. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2009 Dec:37(9):894-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02187.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20092601]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIshikawa S, Shoji T, Nishiyama Y, Shinoda K. A case with acquired lacrimal fistula due to Sjögren's syndrome. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2019 Sep:15():100526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100526. Epub 2019 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 31388605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHan LP, Wang FX, Zhang CY. Special congenital dacryocystocele. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2023 Mar-Apr:39(2):608-610. doi: 10.12669/pjms.39.2.6819. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36950401]

Terrell JA, Mudie LI, Williams KJ, Yen MT. Bilateral Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction in Williams-Beuren Syndrome. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2023 May-Jun 01:39(3):e87-e89. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002341. Epub 2023 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 36805645]

Tam MW, Boyle N. Goldenhar syndrome associated with lacrimal system agenesis: A case report. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2023 Mar:29():101766. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2022.101766. Epub 2022 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 36544754]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePison A, Fau JL, Racy E, Fayet B. Acquired fistula of the lacrimal sac and laisser-faire approach. Description of the natural history of acquired fistulas between the lacrimal sac and the skin occurring before planned endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) and without any treatment of the fistula. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2016 Oct:39(8):687-690. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2016.03.009. Epub 2016 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 27587346]