Introduction

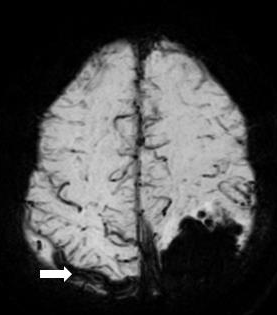

Isolated cortical venous thrombosis (ICVT), also known as cortical vein thrombosis, is a distinct subtype of cerebral venous thrombosis and also a rare cause of stroke (see Image. Cortical Vein Thrombosis). ICVT occurs when a blood clot (thrombus) forms within the cortical vein system but does not involve the dural sinuses, such as the superior sagittal sinus, and transverse sinus. Cortical veins include the superficial cerebral veins, such as the superficial middle cerebral vein, and deep cerebral veins, such as the vein of Galen. Isolated cortical venous thrombosis manifests in a constellation of symptoms such as headache, new-onset seizures, altered consciousness, and focal neurological deficits. If ICVT is not adequately treated, it can cause a cerebral infarction, hemorrhage, or herniation. ICVT is considered a rare cause of stroke and contributes to a mere 6.3% of all cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Risk factors for ICVT include etiologies leading to hypercoagulable states. Protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, G20210 prothrombin gene variant, and factor V Leiden thrombophilia all lead to a hypercoagulable state. Elevated homocysteine levels, factor VIII, and fibrinogen can also increase prothrombotic states.[2] Acquired hypercoagulable conditions include malignancy, oral contraception, oncology medications (tamoxifen, thalidomide, and bevacizumab), pregnancy, estrogen supplementation, hormone replacement therapy, antiphospholipid syndrome, previous history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and myeloproliferative disorders such as essential thrombocytosis or polycythemia vera.[3] Recent studies suggest that infection with SARS-CoV-2 appears to increase the relative risk of cortical venous thrombosis by inducing a hypercoagulable state. Associated hypoxemia with SARS-CoV2 infection increases blood viscosity by activating hypoxia-related genes that initiate coagulation and fibrinolysis, increasing the risk of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.[4]

Epidemiology

Of all cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis, only 6.3% are from ICVT, and ICVT accounts for less than 1% of all cerebral infarctions. One systematic review of 47 case reports/case series found that the mean age of diagnosed patients was 41and 68% of these patients were women.[5] In general, cortical vein thrombosis, isolated cortical vein thrombosis, and cerebral venous thrombosis affect patients younger on average than patients diagnosed with arterial strokes. Women are also at a higher risk than men.[6] Because ICVT is rarely diagnosed, more research is needed to determine additional epidemiological patterns.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of ICVT is similar to cerebral venous thrombosis in that the formation of thrombosis can occlude blood drainage from the cerebral cortex. This lack of blood drainage can lead to increased venous or capillary pressure, which can also increase intracranial pressure—increased venous and capillary pressure results in vasogenic edema. With increasing vasogenic edema and intravenous pressures, venous or capillary vessels can rupture, leading to hemorrhage and dysfunction. If the dural sinuses are specifically occluded, it can decrease cerebrospinal fluid reabsorption, which also increases intracranial pressure.[2] Any of these mechanisms that increase intracranial pressure within the rigid cranium can cause herniation syndrome.

History and Physical

The most common patient presentation is a younger female or male with risk factors. Female risk factors include pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, or infection. Male risk factors include a history of hypercoagulable state, genetic or acquired. The patient will complain of new-onset headaches, seizures, or focal neurological deficits. One study found that papilledema and increased intracranial pressure were not common findings in ICVT.[5] The absence of increased intracranial pressure with focal or generalized seizures associated with aphasia, hemiparesis, hemianopia, and other focal neurological abnormalities should prompt physicians to consider ICVT as a diagnosis.[6] Typically the focal neurological findings involve motor and sensory deficits. Headache is the most common complaint and sometimes is the only presenting symptom. Headache onset varies as some patients present with a gradual increase in headache severity over several days, while others have a rapid and severe headache within minutes. Identifying key risk factors is vital to ensure an accurate diagnosis.[7]

In patients with a past medical history of headaches or migraines with auras, it is important to compare the headache's features with the previous presentations to determine a significant difference. Any new-onset headache with characteristics that differ from their previous headache pattern, new-onset seizures, rapid encephalopathy, or focal neurological symptoms that do not fit typical patterns of stroke should warrant further evaluation. ICVT should be considered in the setting of motor and sensory deficits with a new-onset headache.

Evaluation

Once a clinician suspects ICVT per the history and physical, urgent neuroimaging is warranted in the initial diagnostic workup. There are no pertinent laboratory examinations that can evaluate for ICVT, and the diagnosis is typically made with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV). If the institution does not have MRI, then cranial computed tomography (CT) with CT venography (CTV) can also be an option.[1]

MRI with gradient-echo T2 susceptibility-weighted sequences with MR venography is considered the most sensitive imaging modality for ICVT. Typically the clot will present as an area of hypointensity within the cortical vein only on MRI. If a clot is present within the sinuses, then a diagnosis of cortical venous thrombosis should be considered. Regarding cortical venous thrombosis, one study recommended that "cord sign" seen on non-contrast-enhanced brain CT can point to the diagnosis of CVT. The cord sign describes a hyperattenuating cord appearance seen within a dural venous sinus.[8]

While laboratory tests alone are insufficient for diagnosis, some tests have significant prognostic value. Patients with ICVT with a high pretest probability of thrombophilia should be evaluated for genetic etiologies. A patient could benefit from a screening for protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, G20210 prothrombin gene variant, and factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Evaluation for lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid syndrome should also be considered.

Treatment / Management

Management of ICVT aims to recanalize the occluded vessel and prevent its propagation to other parts of the venous system.[9] This recanalization goal may be achieved through anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) subcutaneously or heparin intravenously, with LMWH being the drug of choice. LMWH and heparin are contraindicated in the setting of any recent cerebral hemorrhage, severe hypertensive episodes, hemorrhagic disorders, and peptic ulcer disease. Particular attention is necessary for patients with chronic kidney disease, as LMWH can accumulate in renal insufficiency. In such instances, heparin may be a more appropriate option.[10] (B3)

In patients with evidence of cerebral herniation, neurosurgery should be consulted, and decompressive craniectomy should be considered. In patients who have evidence of worsening neurologic symptoms despite adequate treatment with LMWH or heparin, mechanical thrombectomy or endovascular thrombolysis may also be an option. In the setting of ICVT, there is a risk of increased intracranial pressure. A neuro-intensive care admission should be considered as frequent ICP monitoring, elevating the head of the bed, administering osmotic agents such as mannitol or hypertonic saline, and allowing permissive hyperventilation with a partial target pressure of carbon dioxide of 30 to 35mmHg may be required. Intravenous dexamethasone is not recommended in treating ICVT. Patients that initially present with seizures, edema, infarction, or hemorrhaging on imaging should be placed on seizure prophylaxis (see Image. Hemorrhagic Infarction of the Brain, Computed Tomography).[11] Levetiracetam or valproate are the first-line drugs of choice. Once the patient is stabilized and discharged, anticoagulation therapy with either warfarin or dabigatran should be considered for a minimum of three months to prevent the recurrence of ICVT.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

ICVT can initially present as a severe headache. Imaging is essential as it aids in differentiating ICVT from subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningoencephalitis, or a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor. Ruling out any acute metabolic encephalopathies due to infection is important. Clinical suspicion for infection should be high in patients presenting with fevers, elevated white blood count with band neutrophils, and positive blood cultures.[13]

ICVT can be the first manifestation of a prothrombotic state. Other potential etiologies that need to be considered or worked up are vasculitis syndromes, primary/secondary thrombocytosis, polycythemia vera, antiphospholipid syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus. If ICVT is suspected or discovered, the patient could benefit from a screening for protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, G20210 prothrombin gene variant, and factor V Leiden thrombophilia.

Prognosis

Overall, ICVT has a favorable prognosis. One systematic review of 325 cases found that more than 90% of patients had good outcomes upon discharge or follow-up within one year. This included complete recovery with a return to baseline status or partial recovery. It is also important to note that most patients had their clinical symptoms recovered earlier than their findings in the neuroimaging. In the systematic review study, the in-hospital mortality was 3.0%. Patients treated with long-term anticoagulation for up to 6 months to have complete or partial recovery of clinical symptoms.[14]

Complications

ICVT complications can include venous infarction, hemorrhage, and worsening vasogenic edema. A transtentorial herniation is a complication of ICVT that can lead to death. In cases where transtentorial herniation is suspected, a hemicraniectomy can be lifesaving. Development of seizures increases in patients who present with seizures, have had seizures in the past, and also present with concomitant supratentorial brain lesions such as focal edema, ischemia, or hemorrhagic infarcts. Severe vision loss is a rare but reported complication.[14]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on the risk factors commonly associated with ICVT. Patients with an elevated risk of hypercoagulable states such as protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, G20210 prothrombin gene variant, and factor V Leiden thrombophilia should be made aware of their risk of forming clots. Having good follow-ups with a PCP and hematologist helps mitigate risk factors. Patients with malignancy should also be aware of their increased risk of clot formation, which could lead to ICVT. Patients on medication such as oral contraception, oncology medicine, estrogen supplementation, and hormone replacement therapy have a higher risk of forming clots. Patients with a previous history of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis are also at a higher risk. Patients with multiple risk factors should be counseled extensively on the risks and benefits of initiating treatment given their past medical history.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Typically patients presenting with focal neurological deficits undergo a code stroke alert protocol. ICVT has the risk of presenting as an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke; thus, special care is necessary for making a rapid and accurate diagnosis. Often inefficient, inaccurate, and disjointed communication can contribute to a delay in treatment. Managing focal neurological deficits involves a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates not just physicians but various other healthcare providers.

Emergency medical services must be activated to rapidly obtain vital information such as last known well time and provide rapid transit to a medical institution. Concomitantly there is coordination with the emergency department for prompt radiological imaging of the brain. Once a patient reaches the emergency department, the nursing team must obtain vascular access while the neurologist begins the assessment using the NIH stroke scale. Technicians are involved in this process for the appropriate transport of the patient. In the meantime, on-call neurosurgery must be notified of the patient for the probable need for mechanical thrombectomy.

The process is multifaceted, and many disciplines are needed in the overall care of this patient. One way to help optimize this process and decrease miscommunication is through medical simulations. One study found that using standardized interprofessional collaborative simulations was an effective learning experience for students entering the healthcare field. This study also found that interprofessional team simulation can be an effective and efficient learning experience for students. It also reveals positive changes in stroke best-practice knowledge and IPC competencies.[15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Luo Y, Tian X, Wang X. Diagnosis and Treatment of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Review. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2018:10():2. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00002. Epub 2018 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 29441008]

Gotoh M, Ohmoto T, Kuyama H. Experimental study of venous circulatory disturbance by dural sinus occlusion. Acta neurochirurgica. 1993:124(2-4):120-6 [PubMed PMID: 8304057]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFerro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F, ISCVT Investigators. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004 Mar:35(3):664-70 [PubMed PMID: 14976332]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCavalcanti DD,Raz E,Shapiro M,Dehkharghani S,Yaghi S,Lillemoe K,Nossek E,Torres J,Jain R,Riina HA,Radmanesh A,Nelson PK, Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Associated with COVID-19. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2020 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 32554424]

Coutinho JM, Gerritsma JJ, Zuurbier SM, Stam J. Isolated cortical vein thrombosis: systematic review of case reports and case series. Stroke. 2014 Jun:45(6):1836-8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004414. Epub 2014 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 24743438]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFerro JM, Canhão P, Bousser MG, Stam J, Barinagarrementeria F, ISCVT Investigators. Cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis in elderly patients. Stroke. 2005 Sep:36(9):1927-32 [PubMed PMID: 16100024]

Jacobs K, Moulin T, Bogousslavsky J, Woimant F, Dehaene I, Tatu L, Besson G, Assouline E, Casselman J. The stroke syndrome of cortical vein thrombosis. Neurology. 1996 Aug:47(2):376-82 [PubMed PMID: 8757007]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAhn TB, Roh JK. A case of cortical vein thrombosis with the cord sign. Archives of neurology. 2003 Sep:60(9):1314-6 [PubMed PMID: 12975301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMinadeo JP, Karaman BA. Headache: cortical vein thrombosis and response to anticoagulation. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1999 May-Jun:17(3):449-53 [PubMed PMID: 10338237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSolari F, Varacallo M. Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247832]

Einhäupl K, Stam J, Bousser MG, De Bruijn SF, Ferro JM, Martinelli I, Masuhr F, European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guideline on the treatment of cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in adult patients. European journal of neurology. 2010 Oct:17(10):1229-35. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03011.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20402748]

Ferro JM, Bousser MG, Canhão P, Coutinho JM, Crassard I, Dentali F, di Minno M, Maino A, Martinelli I, Masuhr F, Aguiar de Sousa D, Stam J, European Stroke Organization. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis - endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. European journal of neurology. 2017 Oct:24(10):1203-1213. doi: 10.1111/ene.13381. Epub 2017 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 28833980]

Singh R, Cope WP, Zhou Z, De Witt ME, Boockvar JA, Tsiouris AJ. Isolated cortical vein thrombosis: case series. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Aug:123(2):427-33. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.JNS141813. Epub 2015 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 25794339]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSong SY, Lan D, Wu XQ, Meng R. The clinical characteristic, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of cerebral cortical vein thrombosis: a systematic review of 325 cases. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis. 2021 Apr:51(3):734-740. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02229-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32737741]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMacKenzie D, Creaser G, Sponagle K, Gubitz G, MacDougall P, Blacquiere D, Miller S, Sarty G. Best practice interprofessional stroke care collaboration and simulation: The student perspective. Journal of interprofessional care. 2017 Nov:31(6):793-796. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1356272. Epub 2017 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 28862889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence