Introduction

The oral cavity is particularly susceptible to the manifestations of viral illnesses.[1] Viral infections often have a subclinical course, and clinical manifestations in the form of oral lesions result from viral cellular destruction or an immune response to viral proteins.[2]

Oral lesions associated with viral conditions are encountered in daily practice by a wide range of healthcare providers, including general practitioners, dentists, otolaryngologists, and dermatologists.[3] Such lesions may pose a diagnostic challenge, as the clinical presentation and the possible causative microorganisms are extensive.[4] DNA viruses, including members of the Herpesviridae, Papillomaviridae, and Poxviridae families, are known to cause oral lesions. RNA viruses, including enteroviruses and paramyxoviruses, can also affect the oral cavity.

Establishing a definitive diagnosis is sometimes tricky.[2] Timely recognition of the lesions reduces the risk of complications. This is particularly important in specific patient populations, like those with HIV or AIDS, as the incidence of oral lesions often correlates with the progression of the disease.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

DNA Viruses

Herpesviridae

The viruses that belong to the Herpesviridae family are the most common cause of viral infections of the oral cavity.[6] All of the viruses within this family can remain latent and subsequently reactivate to develop a secondary infection.[3] More specifically, eight serotypes are known to produce disease in human populations. These include herpes simplex virus (HSV-1 and HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV or HHV-3), cytomegalovirus (CMV or HHV-5), human herpes viruses (HHV-6, HHV-7 or HHV-8) and Epstein-Barr virus (HHV-4).[7]

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis (PHGS)

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is the primary form of infection with herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2). Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 are double-stranded DNA viruses that cause mucocutaneous lesions on the oral and genital mucosa.[7][2] Although HSV-2 is classically known to cause genital infection, it may also manifest in the oral cavity.[3][8] The most common form of transmission is contact with either oral secretions or mucocutaneous lesions.[9][4] Viral shedding may occur despite the absence of physical lesions.[10]

Herpes Labialis

Herpes labialis is the secondary infection with herpes simplex viruses, occurring in about 40% of infected individuals.[1] It results from the reactivation of the dormant virus in the trigeminal ganglion,[3] which can be precipitated by trauma, stress, immunosuppression, and sunlight exposure.[6]

Chicken Pox

Chickenpox is the primary infection associated with the varicella-zoster virus (VZV or HHV-3).[6] The condition is more often seen in pediatric populations.[9] Transmission of viral particles usually occurs via respiratory droplets or contact with infected lesions.[6]

Shingles

Shingles is caused by a secondary infection with the varicella-zoster virus. It occurs due to the reactivation of the dormant virus at the dorsal root ganglion of the spinal nerves, which may occur in immunosuppressed states.[2][3]

Infectious Mononucleosis

Mononucleosis is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV or HHV-4). The Epstein-Barr virus is associated with primary infections but also neoplastic processes.[11] The pathogenesis of mononucleosis primarily involves the infection of B-cells in the oropharyngeal mucosa, where the virus may remain latent.[8][2][4]

The primary transmission mode is via close contact with oral secretions due to viral shedding in saliva.[2] The most common clinical manifestation of infectious mononucleosis, also referred to as "kissing disease" or "glandular fever," is most often seen in adolescent patients.[3]

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia is the most common oral lesion caused by the Epstein-Barr virus in patients with AIDS - usually observed with CD4 counts lower than 200 to 300/mm^3.[5][12] It usually occurs in men and may represent the first sign of HIV infection.[4][12] It is thought to be caused by the replication of viral particles in the mucosal keratinocytes.[13][5]

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus is also a member of the Herpesviridae family and is otherwise known as HHV-5.[5] Viral transmission occurs through the exchange of body fluids or infected blood products. It may cross the placental barrier and, thus, lead to congenital disease. Most cases are asymptomatic, particularly in immunocompetent hosts.[5] However, some immunocompromised individuals may experience chronic oral mucosal ulcerations.[14][5]

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is the most prevalent malignancy seen in untreated HIV patients, and it is associated with the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8).[15] It is important to note that it is most often observed in immunocompromised patients.[2]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papilloma Virus

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that may lead to benign, premalignant, or malignant manifestations in the oral mucosa.[16] Approximately 25 strains have been demonstrated to affect the oral mucosa; however, most subtypes have a low risk of oncogenesis.[1] Transmission occurs primarily through oral or genital contact.[1]

Verruca Vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris is a benign lesion also referred to as the common wart, and it is often caused by HPV subtypes 2 and 57.[8]

Oral Squamous Papilloma

Oral squamous papillomas are the most common growth in the oral cavity.[1] They are benign lesions associated with infection with HPV subtypes 6 and 11.[1] They are often indistinguishable clinically from verruca vulgaris, and thus, differentiation often relies on HPV subtyping.[3] These lesions may be transmitted between sites by autoinoculation.[3]

Condyloma Acuminatum

Condyloma acuminata, also known as genital warts, are caused by the human papillomavirus, mainly subtypes 6 and 11.[17] These lesions are transmitted by sexual contact; hence, they are primarily seen in the genitalia. Oral lesions are due to genital-oral transmission or autoinoculation.[16]

Heck Disease

Heck disease, also known as focal or multifocal epithelial hyperplasia, is caused by HPV infection with subtypes 13 and 32.[14] It is a benign condition that may be seen in adults and children.[3][11]

Poxviridae

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a DNA virus known as Poxvirus.[8] It is often seen in immunocompromised patients and leads to characteristic intraoral lesions accompanying systemic symptoms.[8]

RNA Viruses

Enteroviruses

Enteroviruses, particularly coxsackievirus A and B, are the most common cause of viral infections of the oropharynx.[3] These viral infections usually affect children and cause epidemics every couple of years during summertime.[12]

Herpangina

Herpangina is caused by coxsackievirus A, serotypes explicitly 1-10, 16, and 22.[3] The spread of viral particles occurs through contact with contaminated oral secretions or fecal matter.[3]

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is caused by the coxsackie virus A16 or enterovirus 71 and is most often found in children younger than ten.[18][19] The infection is characterized by a seasonal pattern, with outbreaks in the summer months.[18] The primary transmission mode is through the spread of airborne particles or fecal-oral contamination.[19]

Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis is caused by the coxsackie virus type A serotype 10.[9] The infection is characterized by fever and oral mucosal eruption.

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

Measles, also known as rubeola, is caused by an enveloped RNA virus whose transmission occurs through respiratory droplets. However, the prevalence of measles has significantly decreased due to widespread vaccination.[4]

Epidemiology

DNA Viruses

Herpesviridae

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis (PHGS) and Herpes Labialis

The worldwide infection rates for herpes simplex viruses range between 60 to 90%.[7] The incidence of herpes is slightly increased in populations with low socioeconomic status.[20] Infection with non-genital herpes simplex virus, more commonly HSV-1, has decreased somewhat since the eighties.[21]

The infection is usually acquired in childhood by asymptomatic shedders.[22] Viral shedding in oral secretions is estimated to occur in about 5 to 10% of individuals.

Chicken Pox

The widespread vaccination for varicella has significantly reduced the incidence of chickenpox and its associated morbidity.[23] In 2014, the World Health Organization estimated that about 4.2 million cases of infection developed significant complications, and 4,200 disease-related deaths occurred annually.[24] The vast majority of infections are seen in children.[25]

Shingles

The lifetime incidence of shingles is estimated to be about 30% for the general population, increasing slightly in patients above the age of 85.[26] Important patient factors that increase the risk of infection include patients older than 50, systemic immunosuppression, and stress.[27]

Infectious Mononucleosis

Acquisition of the Epstein-Barr virus usually occurs early in childhood and leads to latent infection. It is estimated that greater than 90% of the global population has acquired EBV.[28] The primary infection, also known as infectious mononucleosis, usually presents during adolescence.[29] About 90% of mononucleosis cases are due to EBV infection.[29]

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia caused by EBV is almost exclusively seen in patients with immunocompromised states, such as those with HIV.[30]

Cytomegalovirus

The reported rate of seropositivity to CMV in the United States is estimated to be 50%. A higher prevalence is seen with increasing age, particularly in developing countries where rates may be as high as 100%.[31] CMV is often acquired during childhood but may also be obtained by vertical transmission.[32]

Kaposi Sarcoma

Four variants of Kaposi sarcoma are recognized, each with specific disease prevalence amongst different patient populations. A classic variant is often seen in males of Mediterranean or Eastern European descent. Patient-specific risk factors, such as chronic steroid use and diabetes, may place them at higher risk.[33] An aggressive variant, African-endemic Kaposi Sarcoma, is most often seen in patients from sub-Saharan Africa and is a frequent carcinoma amongst HIV-negative individuals from this geographic location.[33]

As its name suggests, immunosuppression-related Kaposi Sarcoma is seen in patients with chronic immunosuppression, particularly solid-organ transplant recipients.[33] Finally, AIDS-related Kaposi Sarcoma is most often observed in HIV-infected men. However, after the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, the incidence of the disease has decreased. The infection's risk increases as the immunosuppression become more severe, often seen with lower CD4 counts.[33]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papilloma Virus

Verruca Vulgaris, Oral Squamous Papillomas, Condyloma Acuminatum, and Heck's Disease

The estimated global prevalence of HPV infection is approximately 10%. It is considered the most common sexually transmitted disease, and the highest infection rate is observed in women in their twenties. The prevalence of the disease subsequently decreases with age.[34]

The majority of HPV infections of the oral cavity lead to benign lesions. Squamous papillomas or common warts are most frequently observed in children. Additionally, adults between 30 to 50 years old may also develop oral papillomas. Specific syndromes, such as Down syndrome and Cowden syndrome, have been associated with multiple oral papillomas.[35]

It is worth noting that focal epithelial hyperplasia is associated with a genetic predisposition and is considered an autosomal recessive condition often seen in Native American populations.[35]

Poxviridae

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum mainly develops in pediatric patients.[36] In the US, children between 1 to 4 years old are the most affected by the poxvirus infection.[37] Infection in adults has also been described and, in most cases, occurs in the genital region; therefore considered to be acquired by sexual transmission. It most often occurs in immunocompromised individuals. The infection rate in HIV patients is estimated to be 20%.[38]

RNA Viruses

Enteroviruses

Herpangina, Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease, and Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Enteroviruses are responsible for various clinical conditions, including HFMD, herpangina, and acute lymphonodular pharyngitis. The patient's age may affect the infection's severity and associated complications. The majority of infections are seen in pediatric patients.[39] Epidemics of Enterovirus infections occur most often in the summer and fall; however, they may happen sporadically year-round too. A higher incidence of viral infection is seen in tropical regions.[39]

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

The prevalence of measles has reduced significantly since implementing routine childhood vaccination with the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) jab. This resulted in disease eradication in 2000.[40] However, recent anti-vaccination movements have led to a resurgence of rubeola infection, with hundreds of cases reported in 2019, primarily in unvaccinated individuals.[40]

History and Physical

DNA Viruses

Herpesviridae

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis (PHGS)

As previously stated, PHGS is the primary infection with the herpes simplex virus (HSV-1 and HSV-2). Symptoms usually develop after five to ten days of incubation.[8][4][8] In some patients, the infection is subclinical.[1][13] When oral manifestations become apparent, the classic finding is a generalized inflammation of the gingiva and associated oral tenderness.[1]

The characteristic oral lesions are small vesicles that break and transform into shallow, painful, gray-yellow ulcers.[2][3][6][12] These lesions often involve the gingiva and buccal mucosa.[4] Intact vesicles are a rare physical exam finding due to constant intraoral friction that leads to rupture.[11]

Oral lesions often accompany systemic symptoms, including fever, sore throat, chills, and lymphadenopathy.[2][3][4]

Herpes Labialis

Herpes labialis is the secondary infection with the herpes simplex virus due to the reactivation of the dormant virus.[1] The lesions develop in the perioral region, particularly in the skin of the lips and a vermillion border.[2] However, the keratinized oral mucosa, including the gingiva and palate, may also be affected.[2] See Image. Herpes Labialis.

A burning sensation may precede the eruption.[9] The patient will then subsequently develop areas of erythema and vesicle, which break down and form crusted lesions often referred to as cold sores.[3][6][3]

Chickenpox

Chickenpox is the primary infection with the varicella-zoster virus. The classic skin lesions are pruritic maculopapular and vesicular eruptions with an erythematous base on the trunk that then spread to extremities.[2] The cutaneous eruption is often suggested to have a "dew drop on a rose petal" appearance.[6] The cutaneous manifestations can be preceded by painless blistering on the palate, uvula, and tonsillar pillars.[2][4] See Image. Chickenpox (Varicella).

Shingles

Early signs of shingles are pain or paresthesia affecting a specific dermatome due to the involvement of sensory nerves.[2] This is followed by an eruption of vesicular lesions that often ulcerate and develop overlying crusting.[3] The lesions appear in a specific dermatome with unilateral and linear distributions - characteristic of the condition.[3] Most often, they involve the thoracic or lumbar regions.

Oral involvement is seen when the infection affects the maxillary or mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve.[4][6][12] The prodrome symptom of oral pain caused by shingles infection may be confused with odontalgia leading to incorrect diagnosis or unwarranted medical therapy.[4]

Moreover, a unilateral vesicular eruption on the oral mucosa and external ear may occur and is referred to as Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. It may be accompanied by unilateral facial nerve palsy due to geniculate ganglion involvement.[2][6]

Infectious Mononucleosis

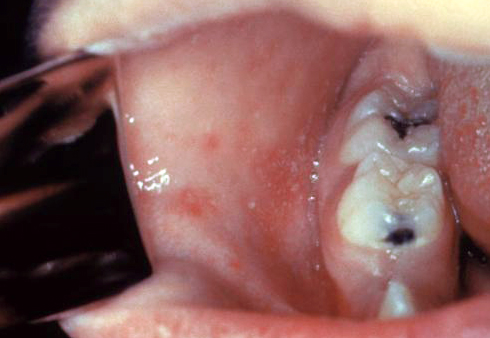

Even though the infection is asymptomatic in most cases, some patients may experience a triad of fever, reactive adenopathy, and pharyngitis.[2] The oral lesions range from petechia and erythema to necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis.[4] See Image. Infectious Mononucleosis.

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia is an asymptomatic, white patch with a "hairy" appearance that cannot be scraped off. It usually develops on the lateral borders of the tongue.[5][4][8]

Cytomegalovirus

Most cases of cytomegalovirus infection are asymptomatic, particularly in immunocompetent hosts.[5] However, some individuals may develop hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and jaundice.[2] Central nervous system (CNS) involvement has also been described.

Some patients may develop non-specific oral mucosal ulcerations, particularly in cases of coinfection with HSV or immunocompromised status. The ulcerations may become chronic and involve the lips, buccal mucosa, and oropharynx.[14][5] Usually, these lesions are seen in patients with CD4 counts <100cells/mm3.[12]

Kaposi Sarcoma

The clinical presentation of HHV-8 is characterized by red, blue, or purple macules, nodules, or plaques on the gingiva, hard palate, or tongue's dorsum. The lesions can be single or multiple.[5][2][4] Ulceration and bleeding have been described.[5]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papillomavirus

Verruca Vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris or common warts are benign oral lesions. They are sessile and papillomatous lesions that classically affect the lips, palate, and gingiva.[8]

Oral Squamous Papilloma

Papillomas are the most common growth in the oral cavity.[1] They are benign pedunculated, exophytic lesions with a "cauliflower" appearance that may involve the palate, including the uvula and lips.[3] It is clinically indistinguishable from verruca vulgaris.[3]

Condyloma Acuminatum

Condyloma acutimatum lesions are transmitted sexually and have been reported in the oral cavity.[4][8] Oral lesions present as white-pink papules or plaques with a pebbled appearance involving labial mucosa and palate.[4][8]

Heck's Disease

Heck's disease is a benign condition that often presents as multiple, painless, white, well-circumscribed papules or plaques in the tongue, labial, and buccal mucosa.[3][4]

Poxviridae

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum infection often occurs in immunocompromised individuals.[8] The associated oral lesions are clustered flesh-toned, smooth papules with central umbilication.[8]

RNA Viruses

Enteroviruses

Herpangina

Herpangina presents as oral vesicular lesions or pseudomembranous ulcers, classically in the posterior oropharynx involving the soft palate and tonsillar pillar. Patients usually report a sore throat.[3]

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by mucocutaneous lesions and flu-like symptoms, including low-grade fever and generalized malaise.[19] Vesicular lesions or bullae appear within the oral cavity, which may subsequently ulcerate. The oral lesions may precede the skin lesions and involve any site of the oral cavity but tend to affect the buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue.[18] The skin lesions begin as macular erythema and progress to vesicles. The vesicles may burst, ulcerate and become painful or coalesce to form larger lesions. Cutaneous lesions classically appear on the palms and soles in a linear distribution.[18] See Image. Hand, Foot, and Mouth Virus, Lesions.

Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis is usually associated with other symptoms such as fever and sore throat. The oral lesions are often described as yellow or pink nodules in the posterior oropharynx.[18]

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

Measles is characterized by three stages. The symptoms of the first stage usually include cough and conjunctivitis. Additionally, patients may develop red macules with a blue or white center located on the buccal mucosa, commonly referred to as Koplik spots (see Image. Kiplik Spots). These may precede the second stage by 48 hours.[4] The second stage brings about a cutaneous eruption of a maculopapular rash that spreads centrifugally. Finally, the resolution is seen in the third stage of the disease.[4]

Evaluation

DNA Viruses

Herpetoviridae

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHGS)

Diagnosis of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is based on history and physical exam findings.[3] The lesions often heal spontaneously within two weeks without scarring.[8] If the lesions fail to resolve within ten days, an alternative diagnosis, such as erythema multiforme or disease recurrence, should be considered.[3]

Recurrence in immunocompetent individuals is rare, and underlying conditions such as acute leukemia should be investigated.[3] Although diagnosis is usually clinical, rises in antibody titers to HHV-1 are confirmatory.[11] Additional modalities for diagnostic testing include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Tzanck testing. Tzanck smears detect cytopathologic changes in epithelial cells highly suggestive of viral infection.[11] A viral culture may also be used and is often considered the gold standard for diagnosis. However, it is not routinely implemented as it causes delays.[11]

Herpes Labialis

Similar to primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, the diagnosis of herpes labialis is based on clinical findings. The anatomical location of herpes labialis allows for clinical distinction from recurrent aphthous ulcers.[11] However, if the diagnosis is questionable, an additional diagnostic evaluation can be performed, including histologic examination, viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, direct immunofluorescence, and in-situ hybridization.[4]

Chicken Pox

Diagnosis is usually based on a classic clinical presentation and physical exam findings.

Shingles

Reactivated herpes zoster infections are diagnosed based on clinical findings. The most typical clinical sign is the unilateral distribution of the lesions along a specific dermatome.[11] Viral cultures, PCR, or serologic testing may allow definitive confirmation if the diagnosis is questionable.[1]

Infectious Mononucleosis

The diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis is established when there is EBV-specific IgM in the serum; this is often performed via a mononuclear spot test (heterophile antibody).[3] A peripheral blood smear may be part of ancillary testing demonstrating abnormal lymphocytes.[3]

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Diagnosis of oral hairy leukoplakia is often established clinically. The histopathological evaluation of the lesion may also detect EBV. It may be performed with PCR, direct immunofluorescence, or in situ hybridization techniques.[4][5][8]

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus infection is usually seen in patients with HIV/AIDS with CD4 counts of <100cells/mm3.[12] Diagnosis of CMV infection is generally established with PCR or serologic testing.[4][11]

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is diagnosed via biopsy, and a PCR identifies the HHV-8.[4][11]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papilloma Virus

Verruca Vulgaris, Oral Squamous Papillomas, Condyloma Acuminatum, and Heck's Disease

Oral lesions associated with HPV infection, including verruca vulgaris, squamous papilloma, condyloma acuminatum, and Heck's disease, usually require a biopsy to establish the diagnosis. Specific HPV subtypes are identified with in situ hybridization DNA techniques.[11]

Poxviridae

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is diagnosed histopathologically. The lesions demonstrate Henderson-Paterson bodies and inclusion bodies in cytoplasm, which are classic findings. Viral identification in the specimen is then performed with in situ hybridization.[11][4]

RNA Viruses

Enteroviruses

Herpangina, Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease, and Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Herpangina, acute lymphonodular pharyngitis, and hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) are diagnosed clinically. Serum antibodies may be present and detected on serologic testing. If the diagnosis is questionable, the virus may be cultured from samples of intact vesicles.[11]

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

Infection is usually diagnosed according to clinical findings. Confirmation with serologic testing may be helpful if the diagnosis is questionable.[4]

Treatment / Management

DNA Viruses

Herpesviridae

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHGS)

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis self-resolves after ten to fourteen days and treatment is directed at alleviating symptoms. Patients should be recommended to bed rest, have a soft diet, and increase fluid intake. Oral pain is managed with systemic or topical analgesics, and secondary infection of the lesions can be prevented with chlorhexidine mouthwashes. Immunocompromised or severely unwell patients must be indicated systemic antivirals.[2] Therapy usually consists of acyclovir 200 mg orally five times daily for five days, initiated within 24 to 48 hours of vesicle eruption.[6][3]

Herpes Labialis

Herpes labialis lesions often heal within two weeks without scar formation. However, topical antiviral medication such as penciclovir or acyclovir 5% cream can be indicated during the prodrome stage to reduce the duration of clinical disease.[2][3] In immunosuppressed populations, acyclovir is the treatment of choice. Intravenous foscarnet is an alternative therapy for acyclovir-resistant strains.[4]

Chicken Pox

Treatment of chickenpox consists of supportive measures: over-the-counter analgesia, increased fluid intake, and a healthy lifestyle. Aspirin should be avoided due to the risk of Reye syndrome.[9] The lesions are no longer contagious five to ten days after the initial presentation once complete crusting has occurred.[41]

Shingles

Shingles infection is treated with supportive measures, and ulcers are expected to heal in approximately three weeks.[12] In immunocompromised patients, treatment for primary infection may require high-dose oral acyclovir.[12]

Infectious Mononucleosis

In most cases, infectious mononucleosis resolves spontaneously; thus, treatment mainly supports patient-specific symptoms. It is essential to avoid oral antibiotics such as amoxicillin or ampicillin due to the risk of developing a cutaneous eruption.[12]

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Treatment of oral hairy leukoplakia involves using topical agents such as 0.1% vitamin A and podophyllum.[4] A combination of 25% podophyllin and 5% acyclovir cream is used without lesion recurrence.[42] In HIV patients, antiretroviral therapy must be initiated or adjusted to optimize the immune status.[4](B3)

Cytomegalovirus

The recommended antimicrobial therapy for CMV infection is usually intravenous ganciclovir. Foscarnet and cidofovir can also be indicated.[2] Similarly to oral hairy leukoplakia, improving immune status with antiretroviral therapy is essential.

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma lesions vary in size and location. Treatment depends on the lesion's specific features and ranges from excision, laser destruction, and sclerosing agents to the use of intralesional chemotherapy and radiation.[5][4]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papillomavirus

Verruca Vulgaris, Oral Squamous Papillomas, Condyloma Acuminatum, and Heck's Disease

Lesions of the oral cavity due to the human papillomavirus, including verruca vulgaris, oral papilloma, and condylomas, require surgical removal. This may be performed with scalpel incision, laser excision, or cryosurgery.[3][11] The vast majority are likely to recur if an appropriate margin is not obtained.[3] Thus, common warts and oral papillomas are usually excised along the base.

Lesions of focal epithelial hyperplasia or Heck's disease may recur in immunocompromised patients. The recommended therapy includes topical imiquimod 5% cream, cidofovir gel, podofilox solution, or intralesional injection of interferon-alpha.[1]

Poxviridae

Molluscum Contagiosum

Lesions associated with molluscum contagiosum are usually removed surgically with cryotherapy or chemical destruction with cantharidin.[43]

Enteroviruses

Herpangina, Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease, and Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

The management of most coxsackie virus A infections is mainly supportive. Symptoms are self-limiting and usually resolve spontaneously within seven to ten days.[19](B3)

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

The incidence of measles infection has significantly reduced after widespread vaccination.[3] However, in cases of infection, the management is mainly supportive.

Treatment with immune serum globulin may be necessary for high-risk populations, including pregnant women, young children, and immunocompromised individuals. It is most effective when administered within six days of exposure to the virus.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Candidiasis

- Primary or secondary syphilis

- Gonorrhea

- Tuberculosis

- Bacterial pharyngitis

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Geographic tongue

Prognosis

Most viral infections in the oral cavity resolve spontaneously and are managed with supportive therapy. However, severe untreated conditions may lead to significant comorbidity. Recognizing specific high-risk viral organisms that may impact patients' prognoses is vital. For example, HPV and herpes viruses are synergistic in developing oral malignancy.[2]

Specifically, EBV, HHV-8, and CMV are associated with malignant neoplasms, including lymphomas, nasopharyngeal or gastric carcinomas, Kaposi's sarcoma, and Castleman's disease.[2]

Complications

DNA Viruses

Herpesviridae

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis (PHGS) and Herpes Labialis

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHGS) and herpes labialis can potentially recur, mainly in immunocompromised patients. The untreated cases lead to the dissemination of the infection.[2]

Additionally, reactivation of HSV-1, particularly in the geniculate ganglion, may lead to Bell palsy.[2] However, the exact mechanism by which the virus causes facial nerve damage remains unclear.

Chicken Pox

In cases of severe chickenpox infection, patients may experience severe complications, including Reye's syndrome, encephalitis, and Guillan Barre.[2][3]

Shingles

Long-term complications of shingles infection include postherpetic neuralgia and severe pain in affected areas after the resolution of the infection. This is due to scarring of the affected sensory nerve. Additionally, patients may experience hyperpigmentation and scarring of affected areas.[2][3][1]

Infectious Mononucleosis

Several complications associated with EBV infection are recognized. These include hepatitis, aplastic anemia, or splenic rupture.[2] EBV infection has also been associated with developing African-endemic Burkitt's lymphoma, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal in immunocompromised populations.[14][5]

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia is a benign lesion, and malignant transformation has not been described. However, due to the location of lesions and potential size, patients may experience mild complications such as oral burning or pain.[30]

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus may lead to complications in at-risk populations, e.g., infection in pregnancy can cause fetal transmission and illness. In immunocompromised patients, the infection may disseminate and cause retinitis and blindness.[8]

Kaposi Sarcoma

Potential complications of Kaposi sarcoma include ulceration and associated bleeding.[5]

Papillomaviridae

Human Papillomavirus

Verruca Vulgaris, Oral Squamous Papillomas, Condyloma Acuminatum, and Heck's Disease

Human papillomavirus infection and its long-term implications are still not completely understood. Most benign lesions are associated with low-risk HPV subtypes, usually cleared from the oral mucosa with time.[35] Common complications include oral discomfort, accidental bite injuries, and cosmetic concerns. However, a significant potential long-term complication is the persistence of the virus in the oral cavity.

A high-risk subtype, HPV-16, is known to remain in the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa and contribute to HPV-positive oropharyngeal malignancy. The risk of HPV persistence in oral mucosa is particularly increased in smokers.[35]

Poxviridae

Molluscum Contagiosum

Generally, the disease resolves within six months, but cases where the condition has remained for several years, have been described.[44] Patients with molluscum contagiosum may experience mild complications such as erythema and swelling of the lesions, known as the BOTE sign.[44]

Additionally, patients with immunodeficiency experience larger and refractory lesions with more extensive involvement of the oral mucosa. Some may also develop eczema molluscorum: eczematous plaques around the lesions.[44]

Enteroviruses

Herpangina, Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease, and Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Oral lesions and pain caused by coxsackie virus infection may result in dehydration. Additionally, those with severe illness may experience neurologic involvement, like encephalitis or aseptic meningitis.[19]

Paramyxoviruses

Measles or Rubeola

Complications of primary measles infection are rare due to decreased disease prevalence; however, several complications were described before vaccination. These included pneumonia, keratoconjunctivitis leading to blindness, and CNS infections, including acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, measles inclusion body encephalitis, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis.[45] Such complications were primarily seen in patients with predisposing factors like immunodeficiency or vitamin A deficiency.[45]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As the information provided in this article suggests, the majority of viral infections of the oral mucosa are benign and self-limiting. However, some conditions may progress and lead to potentially life-threatening complications. Moreover, the development of specific oral lesions of viral nature may suggest undiagnosed immunodeficiency and increase the risk of malignancy.

For this reason, patients should be discouraged from disregarding benign-appearing lesions or mild symptoms. This will allow for adequate treatment initiation, appropriate specialist referral, and optimal disease prevention as warranted.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Viral infections have a preference for targeting the oral mucosa.[1] The oral lesions are, in many cases, the initial manifestation or even the only sign of disease. Additionally, some oral lesions may suggest more serious underlying conditions such as severe immunodeficiency, and a subgroup of viruses, e.g., HPV 16, may place patients at risk of more severe infections or neoplastic processes.[35]

Patients may experience oral pain and systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and generalized malaise. These symptoms prompt patients to seek medical attention, usually through a primary care physician, dentist, or otolaryngologist. Potential complications of these conditions, including decreased oral intake and dehydration, may lead to visits to the emergency department.

In immunocompetent individuals, most viral infections of the oral mucosa resolve after two weeks with symptomatic treatment. However, in some cases, an interprofessional team of physicians may be needed to establish a definitive diagnosis, initiate therapy and refer high-risk patients appropriately. This team involves several clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, and PAs), including primary physicians, dentists, otolaryngologists, pathologists, nurses, and pharmacists.

While clinicians will determine the overall course of diagnosis and management, nursing will help coordinate communication between the various clinical entities, provide patient counsel, and assist in examinations and monitoring patient progress. Pharmacists will verify appropriate agent selection and dosing, as well as perform medication reconciliation. An infectious disease specialty pharmacist may be necessary in more challenging cases to optimize treatment. Open communication between all interprofessional team members is crucial to optimizing the management of these infections.

Proper coordination and communication of the interprofessional healthcare team will minimize morbidity associated with prolonged, severe, or untreated disease.[Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Chickenpox (Varicella). Chickenpox is seen in an unvaccinated child.

Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fatahzadeh M. Oral Manifestations of Viral Infections. Atlas of the oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2017 Sep:25(2):163-170. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2017.04.008. Epub 2017 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 28778305]

Santosh ABR, Muddana K. Viral infections of oral cavity. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2020 Jan:9(1):36-42. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_807_19. Epub 2020 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 32110562]

McIntyre GT. Viral infections of the oral mucosa and perioral region. Dental update. 2001 May:28(4):181-6, 188 [PubMed PMID: 11476033]

Hairston BR,Bruce AJ,Rogers RS 3rd, Viral diseases of the oral mucosa. Dermatologic clinics. 2003 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 12622265]

Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Viral lesions of the mouth in HIV-infected patients. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 1997:194(1):1-7 [PubMed PMID: 9031782]

Bandara HMHN, Samaranayake LP. Viral, bacterial, and fungal infections of the oral mucosa: Types, incidence, predisposing factors, diagnostic algorithms, and management. Periodontology 2000. 2019 Jun:80(1):148-176. doi: 10.1111/prd.12273. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31090135]

Boitsaniuk SI, Levkiv MО, Fedoniuk LY, Kuzniak NB, Bambuliak AV. ACUTE HERPETIC STOMATITIS: CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS, DIAGNOSTICS AND TREATMENT STRATEGIES. Wiadomosci lekarskie (Warsaw, Poland : 1960). 2022:75(1 pt 2):318-323 [PubMed PMID: 35182142]

Tovaru S,Parlatescu I,Tovaru M,Cionca L, Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis in children and adults. Quintessence international (Berlin, Germany : 1985). 2009 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 19169443]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceClarkson E, Mashkoor F, Abdulateef S. Oral Viral Infections: Diagnosis and Management. Dental clinics of North America. 2017 Apr:61(2):351-363. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2016.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28317570]

Wald A. Herpes. Transmission and viral shedding. Dermatologic clinics. 1998 Oct:16(4):795-7, xiv [PubMed PMID: 9891683]

Lynch DP. Oral viral infections. Clinics in dermatology. 2000 Sep-Oct:18(5):619-28 [PubMed PMID: 11134857]

Gondivkar S,Gadbail A,Sarode GS,Sarode SC,Patil S,Awan KH, Infectious diseases of oral cavity. Disease-a-month : DM. 2019 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 30681961]

McCullough MJ, Savage NW. Oral viral infections and the therapeutic use of antiviral agents in dentistry. Australian dental journal. 2005 Dec:50(4 Suppl 2):S31-5 [PubMed PMID: 16416715]

Scully C, Epstein J, Porter S, Cox M. Viruses and chronic disorders involving the human oral mucosa. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1991 Nov:72(5):537-44 [PubMed PMID: 1745511]

Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi's sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2010 Oct:10(10):707-19. doi: 10.1038/nrc2888. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20865011]

Rautava J,Syrjänen S, Human papillomavirus infections in the oral mucosa. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2011 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 21804057]

Pennycook KB, McCready TA. Condyloma Acuminata. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613447]

McKinney RV. Hand, foot, and mouth disease: a viral disease of importance to dentists. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 1975 Jul:91(1):122-7 [PubMed PMID: 1055750]

Nassef C, Ziemer C, Morrell DS. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: a new look at a classic viral rash. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2015 Aug:27(4):486-91. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000246. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26087425]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrimi S,Fiorillo L,Bianchi A,D'Amico C,Amoroso G,Gorassini F,Mastroieni R,Marino S,Scoglio C,Catalano F,Campagna P,Bocchieri S,De Stefano R,Fiorillo MT,Cicciù M, Herpes Virus, Oral Clinical Signs and QoL: Systematic Review of Recent Data. Viruses. 2019 May 21; [PubMed PMID: 31117264]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUsatine RP, Tinitigan R. Nongenital herpes simplex virus. American family physician. 2010 Nov 1:82(9):1075-82 [PubMed PMID: 21121552]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLevin MJ, Weinberg A, Schmid DS. Herpes Simplex Virus and Varicella-Zoster Virus. Microbiology spectrum. 2016 Jun:4(3):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.DMIH2-0017-2015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27337486]

Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Pathogenesis and current approaches to control of varicella-zoster virus infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2013 Oct:26(4):728-43. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00052-13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24092852]

Wutzler P,Bonanni P,Burgess M,Gershon A,Sáfadi MA,Casabona G, Varicella vaccination - the global experience. Expert review of vaccines. 2017 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 28644696]

Edmunds WJ, Brisson M. The effect of vaccination on the epidemiology of varicella zoster virus. The Journal of infection. 2002 May:44(4):211-9 [PubMed PMID: 12099726]

Schmader K. Herpes Zoster. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2016 Aug:32(3):539-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2016.02.011. Epub 2016 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 27394022]

Patil A, Goldust M, Wollina U. Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses. 2022 Jan 19:14(2):. doi: 10.3390/v14020192. Epub 2022 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 35215786]

Kessenich CR,Flanagan M, Diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. The Nurse practitioner. 2015 Aug 15; [PubMed PMID: 26180908]

Rostgaard K, Balfour HH Jr, Jarrett R, Erikstrup C, Pedersen O, Ullum H, Nielsen LP, Voldstedlund M, Hjalgrim H. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection with and without infectious mononucleosis. PloS one. 2019:14(12):e0226436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226436. Epub 2019 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 31846480]

Resnick L, Herbst JS, Raab-Traub N. Oral hairy leukoplakia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1990 Jun:22(6 Pt 2):1278-82 [PubMed PMID: 2163409]

Dioverti MV, Razonable RR. Cytomegalovirus. Microbiology spectrum. 2016 Aug:4(4):. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.DMIH2-0022-2015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27726793]

Griffiths P,Baraniak I,Reeves M, The pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus. The Journal of pathology. 2015 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 25205255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEtemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi Sarcoma Updates. Dermatologic clinics. 2019 Oct:37(4):505-517. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.05.008. Epub 2019 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 31466590]

Boguñá N, Capdevila L, Jané-Salas E. Relationship of human papillomavirus with diseases of the oral cavity. Medicina clinica. 2019 Aug 16:153(4):157-164. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.02.027. Epub 2019 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 31109717]

Syrjänen S. Oral manifestations of human papillomavirus infections. European journal of oral sciences. 2018 Oct:126 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):49-66. doi: 10.1111/eos.12538. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30178562]

Dohil MA,Lin P,Lee J,Lucky AW,Paller AS,Eichenfield LF, The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 16384754]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, Francis NA. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Family practice. 2014 Apr:31(2):130-6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt075. Epub 2013 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 24297468]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGur I. The epidemiology of Molluscum contagiosum in HIV-seropositive patients: a unique entity or insignificant finding? International journal of STD & AIDS. 2008 Aug:19(8):503-6. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008186. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18663032]

Jubelt B, Lipton HL. Enterovirus/picornavirus infections. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2014:123():379-416. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53488-0.00018-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25015496]

Porter A, Goldfarb J. Measles: A dangerous vaccine-preventable disease returns. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2019 Jun:86(6):393-398. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.19065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31204978]

Sauerbrei A. Diagnosis, antiviral therapy, and prophylaxis of varicella-zoster virus infections. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2016 May:35(5):723-34. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2605-0. Epub 2016 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 26873382]

Brasileiro CB, Abreu MH, Mesquita RA. Critical review of topical management of oral hairy leukoplakia. World journal of clinical cases. 2014 Jul 16:2(7):253-6. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i7.253. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25032199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLeung AKC,Barankin B,Hon KLE, Molluscum Contagiosum: An Update. Recent patents on inflammation [PubMed PMID: 28521677]

Meza-Romero R, Navarrete-Dechent C, Downey C. Molluscum contagiosum: an update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2019:12():373-381. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187224. Epub 2019 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 31239742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoss WJ. Measles. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Dec 2:390(10111):2490-2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31463-0. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28673424]