Introduction

Galactoceles, occasionally termed lactocele or a lacteal cyst, are benign milk retention cysts that primarily arise in lactating or recently lactating patients due to a persistent obstruction of the lactiferous duct.[1] The term galactocele is derived from the Greek words galatea, meaning milky white, and cele, meaning pouch, and is the most commonly diagnosed benign breast mass in lactating patients.[2][1] This obstruction of the lactiferous duct causes milk to accumulate in a cystic structure, which can present clinically as a mass of varying size, from a barely palpable mass to a large mass measuring greater than 10 cm.[3] Typically presenting as a moderately firm, painless unilateral or bilateral mass, galactoceles may grow or decrease in size during their clinical course. While galactoceles are generally not associated with pain or inflammation, complications can arise, leading to infection.

Although a galactocele can occur anywhere along the milk line extending from the axilla to the groin, it has a propensity to form in the retroareolar region of the breasts (see Image. Galactocele, Retroareolar Region of Left Breast). Differentiating galactoceles from other breast pathologies, such as cysts, fibroadenomas, abscesses, or malignancies, is essential. Ultrasonography of a galactocele typically reveals a cystic fluid collection, and in symptomatic cases, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) may be performed for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Although many galactoceles resolve spontaneously, symptomatic or infected patients often require medical intervention, including drainage and antibiotics.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

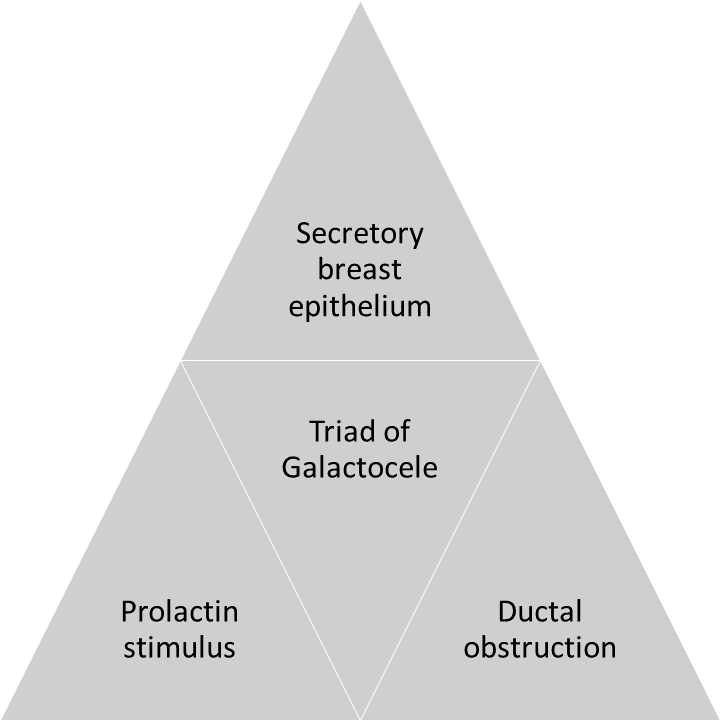

The triad of secretory breast epithelium, prolactin stimulus, and ductal obstruction are needed to develop a galactocele (see Image. Triad of Secretory Breas Epithelium).[5][6]

Secretory Breast Epithelium

Galactoceles most commonly present in patients after lactation cessation; galactoceles may also develop in the third trimester of pregnancy and during lactation. Ductal proliferation is predominantly controlled by estrogen, whereas acinar differentiation is a progesterone effect facilitated by estrogen. These hormones contribute to mammogenesis. The hormonal influence of chorionic gonadotropin forms lobules that have acini with epithelial cells of larger size and number. Small amounts of milk can be secreted as early as week 16 of gestation.[7] Factors that predispose to galactocele formation include:

- Difficulty breastfeeding (eg, infants with cleft palate)

- Infant conditions or settings in which breastfeeding is contraindicated and lactiferous ducts are not emptied [8]

- Phenylketonuria, rare amino acidurias, and classic galactosemia

- Untreated congenital diaphragmatic hernia, esophageal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, intestinal obstruction

- Risk of infant exposure to infectious pathogens via breast milk, such as HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, or Ebola virus

- Risk of infant exposure to maternal medications or radioactive agents via breast milk

- Combined oral contraceptive use due to excessive stimulation of the breast epithelium [5]

Prolactin Stimulus

Approximately 32 cases of galactoceles have been reported in male infants due to transplacental passage of prolactin or a fetal pituitary adenoma causing chronic galactorrhea.[9][10][6] Rarely, galactocele can occur in adult men secondary to hyperprolactinemia.[11] Hyperprolactinemia may be secondary to a prolactinoma, which may be sporadic or associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

Ductal Obstruction

In lactating patients, galactoceles develop due to a reduction in the diameter of lactiferous ductal openings, resulting in milk flow obstruction and accumulation of milk in a cystic cavity.[3] Recently, post–breast-augmentation galactoceles have also been reported; periareolar incisions are a significant risk factor for ductal injury and, subsequently, ductal obstruction. However, breast augmentation procedures performed via the inframammary approach, generally considered protective against the induction of postoperative galactorrhea, have been reported to cause galactocele in some cases.[12][13]

The proposed theory of postsurgical galactocele formation is surgical stimulation of the intercostal nerves leading to autonomic control over central neurogenic paths, diminishing dopamine output into the hypophyseal portal circulation, and increasing circulating prolactin levels and milk secretion.[13] Previous hormonal contraceptive use, pregnancy, and recent breastfeeding may also be contributing factors.[14] However, no genetic etiology or risk factors that increase galactocele formation have been identified.

Epidemiology

In general, benign breast diseases are seen in patients of all ages.[15] The incidence of breast cysts has been reported to increase between the ages of 45 and 50.[15] A palpable breast mass is one of the most common breast complaints in patients seeking medical evaluation.[16] Galactoceles are the most commonly diagnosed benign breast mass in lactating patients.[2][1]

The incidence of galactoceles in patients presenting with benign breast conditions in the nonhospital setting is estimated to be 4%. Additionally, galactoceles are reported in approximately 4% to 5% of breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) category 4 lesion biopsies.[17] However, the incidence may be higher as many galactoceles have mild symptoms and spontaneously resolve without treatment.

Pathophysiology

The primary pathophysiological mechanism of galactocele formation is mammary duct obstruction in the lactating breast. This obstruction may occur secondary to myriad factors, including incorrect breastfeeding techniques, decreased frequency of breastfeeding, trauma, inflammation, nipple abnormalities, or, rarely, an underlying tumor. Distal obstruction of the terminal duct lobular unit results in incomplete ductal emptying and milk accumulation, which causes proximal focal ductal dilatation and galactocele formation.[4][1] Sustained breast trauma, including mild trauma from aggressively squeezing the nipple to relieve a ductal obstruction or a "plugged duct," may precipitate an inflammatory reaction, which leads to galactocele formation.[3]

Transplacental passage of prolactin does not explain the rare development of galactocele in infant boys, who present with a new-onset breast swelling after a period of dormancy of a few months after birth. To explain this phenomenon, experts have hypothesized that neonates develop small retention cysts that remain dormant, with their secretory activity eventually ceasing over time.[18]

Histopathology

Histopathological examination of a galactocele typically reveals ducts lined by normal, flattened cuboidal secreting epithelium and myoepithelium of various sizes.[19][20] The presence of milk is confirmed chemically by a positive mucic acid test. Dilated anastomosing channels are lined by cuboidal epithelium, often with secretory activity. Sometimes, adjacent tissue may show evidence of pressure necrosis, foamy macrophages, and chronic inflammatory changes if cyst contents leak into adjacent tissues.[21][22] Cytologic evaluation of the cyst secretions frequently reveals necrotic cells, nuclear debris, mucins, lipids, lysozymes, albumin, and whey protein.[22]

History and Physical

Clinical History

Galactoceles most commonly form following breastfeeding cessation but may occur during the third trimester or active breastfeeding.[2] Additional historical risk factors for galactoceles include primiparity, difficult breastfeeding, aggressively trying to relieve ductal obstruction, or primarily using formula instead of breast milk due to an incomplete evacuation of milk in the lactiferous ducts.[3] Additionally, clinicians should obtain a medication history, specifically inquiring about galactagogues that increase the risk of galactocele formation, such as metoclopramide and domperidone.[23] Patients may report mild breast discomfort; severe symptoms, such as acute pain, erythema, or fever, are not observed unless the galactocele has become infected.[1]

Physical Examination

The physical examination of a patient with a galactocele will typically reveal a palpable retroareolar mass measuring 1 to 2 cm in diameter; galactoceles greater than 10 cm are uncommon but well-documented.[1] A gradual or rapid fluctuation in size is characteristic of galactoceles, and changes may occur throughout the day, with a brief decrease particularly observed following breastfeeding.[3] Galactoceles may be unilateral or bilateral and solitary or multiple (see Image. Galactocele).[1]

Evaluation

To avoid a missed diagnosis of a breast malignancy, which most commonly presents as a palpable mass, timely diagnostic imaging studies to evaluate these types of breast lesions are critical, even in pregnant and lactating patients.[24] Recommendations regarding the preferred imaging modality in lactating patients are limited; recent evidence-based guidelines have described an optimal approach.[25][20] Subsequently, any new palpable breast mass requires prompt investigation with a three-pronged assessment, including clinical examination, imaging, and aspiration with histologic assessment when needed for confirmation.[4]

Ultrasonography

Lactating patients typically have extremely dense breast tissue due to physiologic changes associated with pregnancy and lactation. Therefore, ultrasonography, which has a higher sensitivity and less radiation exposure than mammography, is the preferred imaging modality for these patients. The optimal imaging modality has historically been less well-defined for patients older than 30 who were pregnant or breastfeeding, for whom the American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria had recommended mammography as the initial imaging modality.[20] Previously, the ACR recommended diagnostic ultrasonography as the initial imaging modality in any lactating or pregnant patient with a palpable breast mass, regardless of age.[24] This recommendation has remained the same for pregnant patients with a new palpable mass.[20]

However, current guidelines have changed for nonpregnant lactating individuals and now recommend that diagnostic imaging indications are the same in nonpregnant lactating and nonlactating patients. Therefore, the ACR now advises that diagnostic ultrasonography is initially indicated in lactating patients younger than 30 with a new palpable mass; in those older than 30, a diagnostic mammogram should be performed initially.[20]

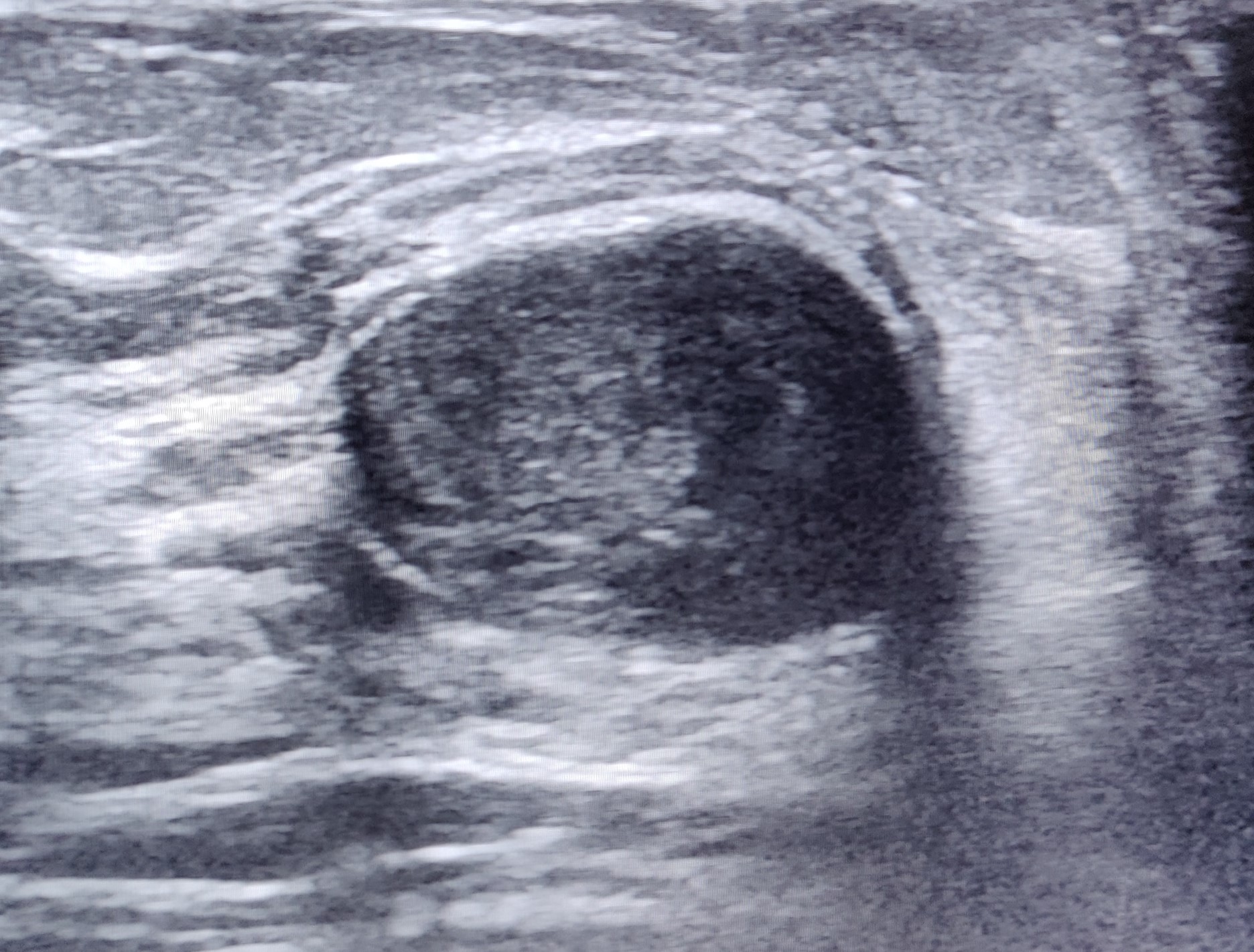

Ultrasonographic features of a galactocele can vary depending on the chronicity of the lesion. In acute cases, the internal contents of the galactocele are a fluid suspension, appearing more homogeneous with medium-level echoes. Conversely, the contents of a persistent galactocele are inspissated material; the appearance is heterogeneous, with internal fluid clefts and anechoic fluid rims (see Image. Inspissated Galactocele). Internal echogenic foci with acoustic shadowing are also secondary to milk products containing about 10% solids, fat, and desquamated epithelium. The distal acoustic enhancement is due to the fluid-filled cyst. The intensity of hypoechoic echo increases gradually due to the interface between the fat and water components.[7]

Ultrasonographic findings characteristic of galactocele include:

- Fat-fluid level, with the hypo- or hyperechogenic fat layer occupying the nondependent or upper part of the cyst

- Circumscribed oval or round shape

- Lack of internal vascularity on Doppler imaging

- Variable echogenicity: echotexture may be heterogeneous depending on fat and protein content

- Posterior acoustic enhancement is frequent, especially in uncomplicated galactoceles

- No internal calcifications; peripheral calcifications may occur in some cases but are generally absent internally [20][24]

Suspicious imaging features should be correlated clinically with signs such as redness, tenderness, and warmth.[26] Color Doppler investigation may be of some benefit in cases of galactocele, as internal vascularity will be absent.[27][19][27] Complex cysts should be carefully differentiated from breast carcinomas. Suspicious or atypical ultrasonographic features of a galactocele include:

- Indistinct or obscured margins

- Posterior acoustic shadowing, mimicking malignancy

- Internal heterogeneous echotexture, which may indicate atypical composition, especially if milk has thickened over time

- Absence of a clear fat-fluid level

- Internal vascularity

- Complex cystic or solid appearance; further investigation (eg, BI-RADS 4) may be warranted to rule out other pathologies [20][24]

Mammography

Diagnostic mammography is recommended as the initial imaging modality in lactating patients older than 30 to evaluate a new palpable breast mass or for further evaluation of a mass in lactating women younger than 30 with suspicious ultrasonographic features.[20] Mammogram findings consistent with a galactocele include:

- Fat-fluid level (seen best on a 90-degree lateral mammogram); characteristic fat layering above the fluid

- Well-circumscribed oval or round shape with smooth borders

- Peripheral rim calcifications [20]

Depending on the protein and fat content of the milk within the galactocele, lesions may have findings similar to other benign conditions, including lipoma, oil cyst, or pseudohamartomas; these findings may include a radiolucent mass or mixed densities.[20] Suspicious findings mammographic findings include:

- Indistinct or obscured margins

- Complex cystic or solid appearance

- Clustered or irregular microcalcifications

- Architectural distortion

- Absence of a pathognomonic fat-fluid level [20]

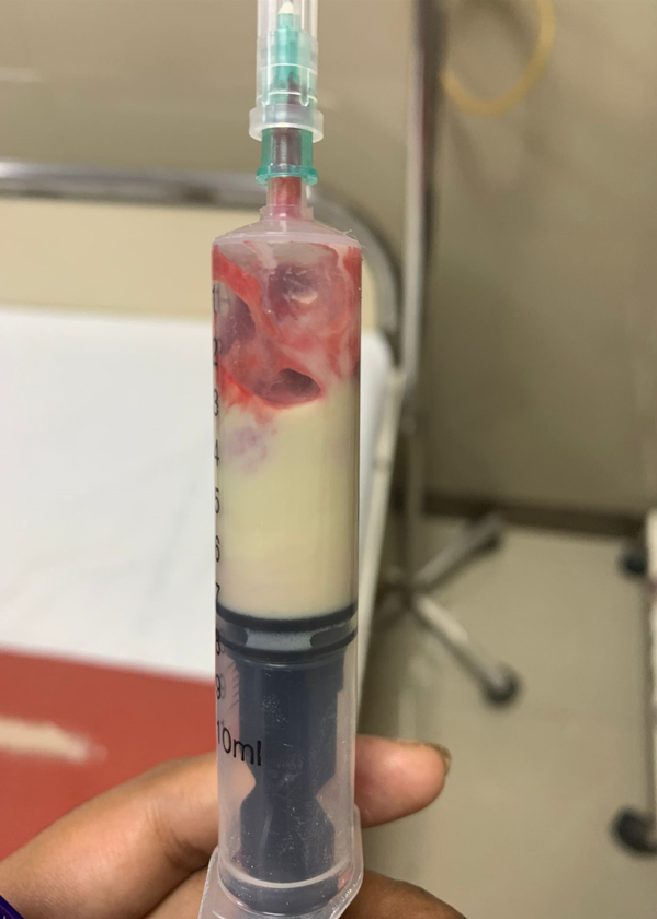

Aspiration may be performed for symptomatic relief or diagnostic confirmation, and in patients with galactoceles, it should yield milky fluid. A biopsy may be recommended to rule out malignancy in patients with infection or atypical imaging features, with BI-RADS categorization as appropriate.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or diagnostic mammography may be performed for additional evaluation in lactating patients with dense breasts or as an initial evaluation in high-risk patients (eg, genetic mutation carriers and women who have received radiation therapy to the thorax or upper abdomen at an early age) aged 30 or older with a new palpable mass.[20] However, MRI is rarely needed for galactocele diagnosis, as ultrasonography is generally adequate for evaluation.[2] MRI will typically reveal a distinct fat-fluid level, which can be visualized by combining non–fat-saturated T1-weighted images (highlighting the fat component) and T2-weighted fat-saturated images (showing the fluid component). When positioned prone, the fat layer may shift towards the chest wall.[20] Additional MRI features can include a thin septation and heterogeneous internal content within the cyst, confirming the diagnosis.[2]

Treatment / Management

Conservative Management

The treatment of a galactocele is dictated by symptom severity, lesional size, and the presence of infection. Observation is the primary management approach for most asymptomatic galactoceles, which typically spontaneously resolve. Conservative measures should be advised, including anti-inflammatory medication as needed, avoidance of over-frequent pumping, and on-demand breastfeeding or pumping. Ice packs and breast support may be helpful.[28][3][1]

Galactocele Aspiration and Catheter-Drainage

Large and symptomatic galactoceles often require intervention, typically with serial aspirations or drainage catheter placement by a breast surgeon for relief and diagnostic confirmation (see Image. Fine Needle Aspiration Specimen of Galactocele).[3] Surgical drainage is generally avoided in favor of less invasive approaches, as aspiration or catheter drainage is typically sufficient.[28] Drainage alleviates symptoms and somewhat reduces mass effect, aiding in breastfeeding.[3][1]

However, aspiration does not decrease surrounding tissue edema; cavities often refill and frequently require repeated aspiration.[28][3] Repeated aspirations can increase the risk of infection. Therefore, catheter drainage is generally preferred over multiple aspirations to prevent the conversion of a sterile galactocele to an infected one.[3]

Management of Infected Galactoceles

If infection develops, drainage and antibiotics are indicated. Initial antibiotic therapy typically includes dicloxacillin or flucloxacillin 500 mg 4 times daily for 10 to 14 days, which treats the most common infectious organisms, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.[3][1] Cloxacillin may be administered if typical antibiotics are unavailable, although cloxacillin has variable bioavailability. Cephalexin is also an option, as it provides broader gram-negative coverage and does not require administration separate from meals.[3]

If first-line antibiotics are ineffective or contraindicated, as in cases of penicillin allergy, second-line options include clindamycin 300 mg 4 times daily for 10 to 14 days or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice daily for 10 to 14 days. However, the latter should be used cautiously in mothers of infants under 30 days old, those with G6PD deficiency, or preterm infants due to the risk of hyperbilirubinemia.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should be considered when evaluating patients with clinical features of a galactocele include:

- Breast cyst

- Breast abscess

- Breast carcinoma

- Fibrocystic changes

- Fibroadenomas

- Lactating adenoma

- Phlegmon

- Prominent lactiferous sinus

- Traumatic fat necrosis

- Hematoma

- Hamartoma [1]

Prognosis

Galactocele is a benign condition that typically resolves spontaneously upon cessation of lactation without any intervention. Therefore, it has an excellent prognosis. No increased risk of subsequent breast cancer or fibrocystic disease after galactocele has been reported.[29]

Complications

Inspissated Galactoceles

Galactoceles usually resolve spontaneously as the rapid hormonal changes linked to lactation stabilize. However, in some cases, desquamated epithelial cells and stagnated milk result in an inspissated cyst forming crystals. This leads to the development of a crystalizing or solid galactocele, a rare entity with only approximately 10 reported cases in the literature.[30][31][32][22] Inspissated galactocels are not easily diagnosed by ultrasound as they do not have any typical features of a galactocele and may even be mistaken for other benign or solid breast lesions (see Image. Inspissated Galactocele).

Fine-needle aspiration of inspissated galactoceles retrieves thick, chalky white material with a gritty sensation noted during aspiration. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the aspirate reveals well-defined purple crystals. Leishman staining demonstrates discrete and polymorphic refractile crystals. These crystals are positively birefringent with surrounding amorphous proteinaceous material. Crystallized galactoceles cannot be emptied by aspiration alone and may require further intervention, like excision.[22]

Infected Galactoceles

Another complication associated with galactoceles is infection. The rich nutrient content of milk in galactocele with a possible unsterile technique of aspiration or excision may lead to acute mastitis, which can become further complicated by the formation of a breast abscess.[28] Clinically, the affected breast becomes swollen and tender, with signs of inflammation present. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism, followed by streptococci. These common pathogens are present in the nose and throat of nursing infants and infect the breast via the damaged epithelial interface of the nipple-areolar complex. An infected galactocele appears as a complex cyst with thickened walls during ultrasonography.[3]

Treatment includes intravenous antibiotics and aspiration or surgical drainage. (Please refer to "Management of Infected Galactoceles" in the Treatment section for more information on managing this complication). Sometimes, a breast implant, which is a known predisposing factor, may also get infected with an infected galactocele, necessitating implant removal along with incision and drainage of the abscess.[33][28] Breastfeeding should continue because it promotes drainage. A milk fistula is a rare complication following aspiration or drain placement of an infected galactocele or breast abscess.[3]

Consultations

Consultations for galactocele management may include:

- Radiologist

- Interventional radiologists

- General surgeon

- Lactation consultant

- Obstetrician and gynecologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

All postpartum patients and neonates must receive postnatal care within the first 24 hours. All postpartum patients should be offered help to teach the best practices in breastfeeding the newborn with the correct technique. Nurse practitioners, midwives, and lactation specialists have an essential role in the prevention, early diagnosis, and prompt referral of lactating patients with breast lumps. The nurse practitioner plays a vital role in educating the patients and their families about their condition.

Regular follow-up visits must be encouraged to ensure the health of postpartum patients and infants. Patients must be counseled about the importance of breast hygiene during lactation. Proper counseling and education of postpartum patients regarding their health cannot be overemphasized. If available, counseling and education can be performed using information leaflets and posters or referrals to educational websites.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is essential in managing galactoceles, as these commonly occur in lactating patients and often resolve with conservative management. This team, composed of physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, lactation specialists, radiologists, and pharmacists, collaborates to provide patient-centered care. Early diagnosis and treatment benefit from a holistic, integrated approach where team members leverage their expertise. Physicians, for example, can ensure a thorough assessment and involve radiologists for imaging in cases that require further investigation, particularly with unusual presentations like galactoceles in infants or nonlactating patients. When ultrasound-guided FNA is performed, communication with cytopathologists is essential for an accurate diagnosis, and effective collaboration with radiologists and pathologists is fundamental to achieving optimal outcomes.

In cases where a galactocele becomes complicated by infection, the extracted pus is cultured, and a microbiologist’s input guides antibiotic choice based on sensitivity reports, enhancing patient safety and treatment efficacy. Shared decision-making between clinicians and surgeons, with a tailored approach to drainage interventions, further supports patient-centered care. Nurses play a critical role by monitoring vital signs, educating patients and families on self-care and breastfeeding practices, and providing emotional support. This coordinated interprofessional communication and care strategy optimizes patient outcomes and team performance, ensuring patient safety remains central throughout the care continuum.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mitchell KB, Johnson HM, Eglash A, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #30: Breast Masses, Breast Complaints, and Diagnostic Breast Imaging in the Lactating Woman. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 2019 May:14(4):208-214. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.29124.kjm. Epub 2019 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 30892931]

Nissan N, Bauer E, Moss Massasa EE, Sklair-Levy M. Breast MRI during pregnancy and lactation: clinical challenges and technical advances. Insights into imaging. 2022 Apr 9:13(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13244-022-01214-7. Epub 2022 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 35397082]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitchell KB, Johnson HM, Rodríguez JM, Eglash A, Scherzinger C, Zakarija-Grkovic I, Cash KW, Berens P, Miller B, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36: The Mastitis Spectrum, Revised 2022. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 2022 May:17(5):360-376. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2022.29207.kbm. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35576513]

Taib NA, Rahmat K. Benign Disorders of the Breast in Pregnancy and Lactation. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2020:1252():43-51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-41596-9_6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32816261]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWINKLER JM. GALACTOCELE OF THE BREAST. American journal of surgery. 1964 Sep:108():357-60 [PubMed PMID: 14215116]

Algethami NE, Taha A, Altalhi WA, Alsulaimani AI. Does Male Infantile Galactocele Always Necessitate Surgical Intervention? Cureus. 2021 Sep:13(9):e18001. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18001. Epub 2021 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 34667677]

Yu JH, Kim MJ, Cho H, Liu HJ, Han SJ, Ahn TG. Breast diseases during pregnancy and lactation. Obstetrics & gynecology science. 2013 May:56(3):143-59. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2013.56.3.143. Epub 2013 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 24327995]

Lawrence RM. Circumstances when breastfeeding is contraindicated. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2013 Feb:60(1):295-318. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.09.012. Epub 2012 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 23178071]

Vlahovic A, Djuricic S, Todorovic S, Djukic M, Milanovic D, Vujanic GM. Galactocele in male infants: report of two cases and review of the literature. European journal of pediatric surgery : official journal of Austrian Association of Pediatric Surgery ... [et al] = Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie. 2012 Jun:22(3):246-50. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1308694. Epub 2012 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 22570125]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoyle M, Lakhoo K, Ramani P. Galactocele in a male infant: case report and review of literature. Pediatric pathology. 1993 May-Jun:13(3):305-8 [PubMed PMID: 8516225]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBandyopadhyay A, Sen K, Chakrabarti N, Datta S. Galactocele of adult male breast: A cytopathologist's perspective. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2019 Feb:47(2):134-136. doi: 10.1002/dc.24101. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30461216]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuerra M, Codolini L, Cavalieri E, Redi U, Ribuffo D. Galactocele After Aesthetic Breast Augmentation with Silicone Implants: An Uncommon Presentation. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2019 Apr:43(2):366-369. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1266-z. Epub 2018 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 30456639]

Rosique RG, Rosique MJ, Peretti JP. Postaugmentation Galactocele Without Periareolar Incision and 8 Years After Pregnancy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2016 Mar:4(3):e644. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000648. Epub 2016 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 27257574]

Sharma SC,Basu NN, Galactorrhea/Galactocele After Breast Augmentation: A Systematic Review. Annals of plastic surgery. 2021 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 32079808]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJohansson A, Christakou AE, Iftimi A, Eriksson M, Tapia J, Skoog L, Benz CC, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Hall P, Czene K, Lindström LS. Characterization of Benign Breast Diseases and Association With Age, Hormonal Factors, and Family History of Breast Cancer Among Women in Sweden. JAMA network open. 2021 Jun 1:4(6):e2114716. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14716. Epub 2021 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 34170304]

Salzman B, Collins E, Hersh L. Common Breast Problems. American family physician. 2019 Apr 15:99(8):505-514 [PubMed PMID: 30990294]

Whang IY, Lee J, Kim KT. Galactocele as a changing axillary lump in a pregnant woman. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2007 Oct:276(4):379-82 [PubMed PMID: 17406878]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBouhassira J, Haddad K, Burin des Roziers B, Achouche J, Cartier S. [Lactation after breast plastic surgery: literature review]. Annales de chirurgie plastique et esthetique. 2015 Feb:60(1):54-60. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2014.07.014. Epub 2014 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 25147123]

Vashi R, Hooley R, Butler R, Geisel J, Philpotts L. Breast imaging of the pregnant and lactating patient: physiologic changes and common benign entities. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Feb:200(2):329-36. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9845. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23345354]

Peterson MS, Gegios AR, Elezaby MA, Salkowski LR, Woods RW, Narayan AK, Strigel RM, Roy M, Fowler AM. Breast Imaging and Intervention during Pregnancy and Lactation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2023 Oct:43(10):e230014. doi: 10.1148/rg.230014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37708073]

Nikumbh DB, Desai SR, Shrigondekar PA, Brahmnalkar A, Mane AM. Crystallizing galactocele - an unusual diagnosis on fine needle aspiration cytology. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2013 Mar:7(3):604-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4583.2821. Epub 2013 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 23634434]

Singla T, Singla G, Singla S, Singh M. FNAC Diagnosis of Crystallizing Galactocele- An Unusual Presentation. Journal of cytology. 2020 Jul-Sep:37(3):149-150. doi: 10.4103/JOC.JOC_18_20. Epub 2020 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 33088035]

Gabay MP. Galactogogues: medications that induce lactation. Journal of human lactation : official journal of International Lactation Consultant Association. 2002 Aug:18(3):274-9 [PubMed PMID: 12192964]

Expert Panel on Breast Imaging:, diFlorio-Alexander RM, Slanetz PJ, Moy L, Baron P, Didwania AD, Heller SL, Holbrook AI, Lewin AA, Lourenco AP, Mehta TS, Niell BL, Stuckey AR, Tuscano DS, Vincoff NS, Weinstein SP, Newell MS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Breast Imaging of Pregnant and Lactating Women. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2018 Nov:15(11S):S263-S275. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30392595]

Chung M, Hayward JH, Woodard GA, Knobel A, Greenwood HI, Ray KM, Joe BN, Lee AY. US as the Primary Imaging Modality in the Evaluation of Palpable Breast Masses in Breastfeeding Women, Including Those of Advanced Maternal Age. Radiology. 2020 Nov:297(2):316-324. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201036. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32870133]

Faguy K. Breast disorders in pregnant and lactating women. Radiologic technology. 2015 Mar-Apr:86(4):419M-438M; quiz 439M-442M [PubMed PMID: 25835417]

Son EJ, Oh KK, Kim EK. Pregnancy-associated breast disease: radiologic features and diagnostic dilemmas. Yonsei medical journal. 2006 Feb 28:47(1):34-42 [PubMed PMID: 16502483]

Kornfeld H, Johnson A, Soares M, Mitchell K. Management of Infected Galactocele and Breast Implant with Uninterrupted Breastfeeding. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2021 Nov:9(11):e3943. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003943. Epub 2021 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 34804762]

Scott-Conner CE, Schorr SJ. The diagnosis and management of breast problems during pregnancy and lactation. American journal of surgery. 1995 Oct:170(4):401-5 [PubMed PMID: 7573738]

Varshney B, Bharti JN, Saha S, Sharma N. Crystallising galactocele of the breast: a rare cytological diagnosis. BMJ case reports. 2021 May 25:14(5):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242888. Epub 2021 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 34035028]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJaseem Hassan M, Sharma M, Khetrapal S, Khan S, Jetley S. Cytological diagnosis of crystallizing galactocele - report of an unusual case. Breast disease. 2018:37(3):159-161. doi: 10.3233/BD-170295. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29286912]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUmasankar P, Lakshmi Priya U, Sideeque A. Crystallizing Galactocele: A rare entity-report of two cases. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2018 Oct:46(10):873-875. doi: 10.1002/dc.24047. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30144343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLam E, Chan T, Wiseman SM. Breast abscess: evidence based management recommendations. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2014 Jul:12(7):753-62. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.913982. Epub 2014 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 24791941]