Introduction

The larynx is a dynamic, flexible structure composed of a cartilaginous core with interconnecting membranes and associated musculature. The larynx is a midline structure positioned at the interface between the digestive and respiratory tracts. In addition to housing the vocal cords and producing phonation, the larynx assists with multiple other functions including but not limited to: airway protection, regulating intrathoracic pressures, and regulating intra-abdominal pressures. The anatomical position, composition, associated musculature and innervation of the larynx all contribute to this structure’s capabilities.[1][2][3]

Laryngeal Position

The anatomical position of the larynx is also dynamic in nature and varies from birth to maturity. Initially, at birth and for the first couple years of life, the larynx is further superior in the neck than in adults. In infants, this high position results in direct contact between the soft palate and epiglottis. This allows inspired air to move from the nose to the trachea directly. It is because of this anatomical relationship; an infant is able to swallow liquids and breathe almost simultaneously.

By adulthood, the larynx descends inferiorly to its final position. The larynx is found within the visceral compartment of the neck and serves as the “floor” of the anterior triangle of the neck. The larynx is the superior portion of the respiratory tract and aligned on its long axis, is vertically adjacent to the trachea, which lies directly inferior to the larynx and is connected via the cricotracheal ligament. Anterosuperiorly, the larynx articulates with the hyoid bone via the thyrohyoid membrane. Dorsally, the larynx attaches to the muscular walls of the pharynx.

Laryngeal Skeleton

The larynx is composed of nine contributing cartilages: three unpaired cartilages and three paired cartilages, which share connections to each other, the hyoid (superiorly), and the trachea (inferiorly). The epiglottic, thyroid, and cricoid cartilages make up the three unpaired cartilages and are arranged superior to inferior respectively. The thyroid cartilage, with the epiglottic cartilage superior, predominates anteriorly and forms the laryngeal prominence (i.e., Adam’s Apple), while the predominate cartilage dorsally is the cricoid cartilage which sits inferior to the thyroid cartilage. The three paired cartilages include the arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform cartilages. The paired arytenoid cartilages are found on the dorsal aspect of the larynx, attached superiorly to the cricoid cartilage. Both arytenoid cartilages give off a lateral extension (muscular process) and anterior extension (vocal process) which aid in supporting the vocal ligaments. Additionally, each arytenoid cartilage has an associated corniculate and cuneiform cartilage. These two small, paired cartilages border the opening into the laryngeal vestibule both dorsally and laterally. The corniculate cartilage can be found at the apex of both arytenoid cartilages. The cuneiform cartilage can be found sitting anterior and lateral to both arytenoids. These cartilages form connections via numerous membranes, ligaments, and synovial joints.

There are two essential synovial joints associated with the larynx. One pair of synovial joints exists between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages. This joint allows the thyroid cartilage to rotate about the cricoid cartilage and allows the cricoid cartilage to separate from or approximate to the thyroid cartilage anteriorly. The second set of synovial joints exists between the cricoid and arytenoids (cricoarytenoid synovial joint). The cricoarytenoid synovial joint allows the arytenoid cartilages to translate on both an anterior-posterior axis and lateral-medial axis, as well as rotate about a cranial-caudal axis.

Laryngeal Folds and Membranes

The aryepiglottic folds extend over the lateral aspects of epiglottic, cuneiform, corniculate and arytenoid cartilages. The aryepiglottic folds demarcate the opening into the laryngeal lumen. The piriform sinus can be found just lateral to the aryepiglottic folds, which form the medial border of these sinuses. This is sometimes referred to as the lateral food channel. The aryepiglottic folds serve as a protective wall that prevents food from passing into the laryngeal aditus and together, with the associated cartilages forms a protective ring. This ring is not uniform in height, at the dorsal-most aspect, there is a reduction in the height of this fold creating susceptibility to food or liquid incursions. This is called the interarytenoid notch.

The laryngeal ventricle is the fossa or sinus that lies between the vocal and vestibular folds on either side. The vocal folds are commonly referred to as the vocal cords and the vestibular folds as the false vocal cords. The laryngeal ventricle also demarcates the separation between the quadrangular membrane superiorly, and the cricovocal membrane found inferiorly. These two membranes together cover the entire interior portion of the larynx from the epiglottic and arytenoid cartilages superiorly to the cricoid cartilage inferiorly. These membranes are bilateral.

The quadrangle membrane gives support to the aryepiglottic folds superiorly and continues inferiorly as the vestibular folds. The vestibular folds contain the vestibular ligament, which extends from the arytenoid cartilage to the thyroid cartilage. The vestibular folds appear to have no role in phonation and are relatively immobile structures.

The laryngeal ventricle begins inferiorly to the free edge of the vestibular fold and continues laterally. The ventricle exists bilaterally, and secretes mucus over the superior surface of the vocal folds, forming a protective layer.

The lateral cricothyroid ligament is contained within the cricovocal membrane. Like the vestibular ligament, this ligament also extends from the arytenoid cartilage to the thyroid cartilage. However, the lateral cricothyroid ligament also follows the cricoid cartilage as it extends inferiorly. In addition, this ligament gives rise to the vocal ligament as it thickens superiorly. The vocal ligament extends from the thyroid cartilage [luminal surface] to the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage. The conus elasticus is a collective term for the cricovocal membrane and its contained ligaments. The medial convergence of these ligaments support the vocal folds.

The vocal folds, also known as the true vocal cords, are medial projections of the walls of the larynx that can approximate to each other in the midline to completely obstruct the lumen of the larynx. These vocal folds delineate the plane referred to as the glottis. Within these vocal folds is a muscle known as vocalis muscle which runs aside the vocal ligament. The ligament and lack of blood vessels on the surface of the folds result in the characteristic white appearance of the pair of vocal folds. This provides visual distinction compared to the pink appearing vestibular folds. The space found between the vocal folds is termed the rima glottides.

Laryngeal Cavity

The laryngeal inlet/aditus is used to refer to the entrance of the cavity of the larynx. Superior to the inlet is the laryngopharynx.

The cavity of the larynx is divided into three regions:

- Supraglottic space: at the level of the vestibular folds. Bounded anteriorly by epiglottis, laterally by the aryepiglottic folds and posteriorly by the inter arytenoid mucosa.

- Laryngeal ventricles: The middle region of the laryngeal cavities is composed of the paired laryngeal ventricles that fall between the vestibular and vocal folds.

- Subglottic space: also referred to as the infraglottic space, continues downward as far inferior as the junction between the cricoid and trachea.

Embryology

The larynx is a complex structure of the respiratory tract composed of unpaired and paired cartilages and originates embryologically from both endoderm and mesoderm.

The respiratory diverticulum also referred to as the lung bud, originates from the foregut during the 4 weeks of development. The lung bud forms due to an increase in retinoic acid produced by the nearby mesoderm. This then leads to an upregulation of transcription factor expressed in the foregut endoderm at the site of the respiratory diverticulum. Thus, the inner lining of the respiratory tract including the larynx, are derived from endoderm.

The connective tissue, muscular and cartilaginous portions of the larynx are derived from the fourth-sixth pharyngeal arches. The cartilaginous components of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches result in the formation of the following laryngeal cartilages: cricoid, thyroid, cuneiform, corniculate, and arytenoid. The intrinsic muscles of the larynx, as well as the cricothyroid muscle, are also derived from the fourth-sixth pharyngeal arches.

One thing to note is that the epiglottis and its cartilages are not derived from these same pharyngeal arches as the rest of the laryngeal structures. The epiglottis does not appear to have origination from a pharyngeal arch as it develops later in mammals.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vascular supply for the larynx is derived from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. The external carotid artery gives rise to the superior thyroid artery. The thyrocervical artery, which arises from the anterosuperior surface of the subclavian artery gives rise to the inferior thyroid artery and two other branches.

The venous drainage of the larynx is via the inferior, middle, and superior thyroid veins. The inferior thyroid veins continue via the subclavian or left brachiocephalic vein. The middle and superior thyroid veins empty into the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatic drainage of the larynx is accomplished via the deep cervical and paratracheal nodes medially, and via the pretracheal and pre-laryngeal nodes medially.

Nerves

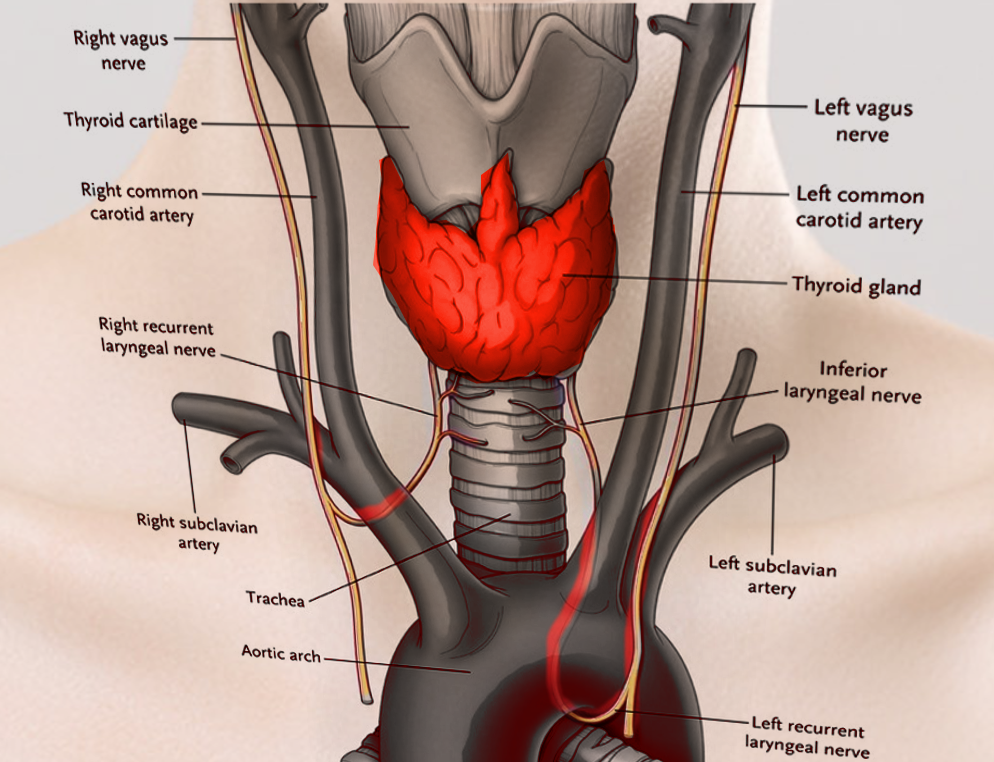

The larynx is innervated by the superior laryngeal nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and sympathetic fibers.[4][5][6][7]

Superior laryngeal nerve: The superior laryngeal nerve [SLN]branches off the vagus approximately 2.5cm below the base of the skull. The SLN has an internal and external branch.

- Internal laryngeal nerve: sensory and autonomic innervation to the mucosa superior to the glottis. This includes general sensory innervation to the superior portion of the laryngeal cavity, including the epiglottis and superior surface of the vocal folds. Visceral afferents to the epiglottis also assist in taste. Preganglionic parasympathetic fibers also travel via the internal laryngeal nerve.

- External laryngeal nerve: supplies motor innervation and visceral efferent to the cricothyroid muscle.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve [RLN]: the RLN is also a branch of the vagus nerve. The left RLN is found inferior to the aortic arch and posterior to ligamentum arteriosum. The right vagus continues posteriorly to the root of the right lung giving off the right RLN which loops around the right subclavian artery.

The recurrent laryngeal nerves then continue superiorly bilaterally and pass posterior to the lobe of the thyroid gland as they travel along the lateral surfaces of the trachea and esophagus in the tracheoesophageal groove. The nerves pass posterior to the cricothyroid joint as they enter the larynx at this level through fibers of the inferior constrictor muscles of the pharynx. At this point, the RLN becomes the inferior laryngeal nerve.

- Inferior laryngeal branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve: excluding the cricothyroid muscle [innervated by the superior laryngeal nerve], the inferior laryngeal branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve innervates all intrinsic muscles of the larynx.

- The recurrent laryngeal nerves also carry general visceral sensory fibers from the region inferior to the glottis.

- The recurrent laryngeal nerve also sends branches to the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus muscles prior to entering the larynx.

Muscles

The muscles of the larynx are can be categorized as intrinsic muscles which function in phonation or extrinsic muscles which produce gross movements of the larynx.

Intrinsic Muscles: The intrinsic muscles of the larynx are responsible for sound production and the movements of the laryngeal cartilages and folds themselves. Their attachments fall between laryngeal cartilages. With the exception of the transverse arytenoid muscle, these muscles are paired bilaterally.

- Oblique arytenoid muscle: spans one dorsal aspect of the arytenoid cartilage to the other cartilage on the opposite side. Adducts arytenoid cartilages.

- Transverse arytenoid muscle: spans one dorsal aspect of the arytenoid cartilage to the other cartilage on the opposite side. Adducts arytenoid cartilages.

- Aryepiglottic muscle: aligns with oblique arytenoid muscles and continues with the aryepiglottic fold. Adducts aryepiglottic folds.

- Thyroepiglottic muscle: extends from the epiglottis to the thyroid cartilage. Contraction widens the inlet and causes depression of the epiglottis.

- Posterior cricoarytenoid muscle: extends from the cricoid cartilage and attaches to the muscular process of each arytenoid. These are the only muscle pair to cause abduction of the vocal folds.

- Lateral cricoarytenoid muscle: extends from cricoid cartilage [arch] to muscular process of the arytenoid cartilage. Adducts vocal folds.

- Thyroarytenoid muscle: extends from angle of the thyroid cartilage to arytenoid cartilage. They pull the arytenoid anteriorly, relaxing the vocal folds. They also approximate the vocal folds.

- Vocalis muscle: They continue along the lateral aspect of the vocal ligament and shorten the vocal folds.

- Cricothyroid muscle: these muscles do not attach the arytenoid cartilages. They run along the lateral cricoid cartilage. This muscle has two bellies that run superior-inferior. The superior belly attaches to the inferior of the thyroid lamina. The inferior belly attaches to the inferior horn of the thyroid cartilage. These muscles lengthen the vocal folds.

Extrinsic Muscles: These muscles are found in bilateral pairs and aid in the movement of the larynx at a gross level. Innervations of the extrinsic laryngeal muscles vary and include the following nerves: ansa cervicalis, trigeminal nerve, facial nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve, and hypoglossal nerve. The pharyngeal constrictors and palatopharyngeus receive innervation from the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and spinal accessory nerve via the “pharyngeal plexus."

Extrinsic muscles that attach directly to the larynx:

- Sternothyroid muscle: attaches to the anterolateral aspect of the thyroid and sternum. Causes laryngeal depression.

- Thyrohyoid muscle: inserts superior and medially compared to the location of the sternothyroid muscles on the thyroid. Causes laryngeal elevation.

- Inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles: attaches anteriorly along the lateral regions of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages, and runs superiorly and posteriorly to meet with opposing fibers at the posterior median raphe of the pharynx. This muscle elevates the larynx. Also, it provides the only connection of larynx to the skull.

Extrinsic muscles that do not attach directly to the larynx: may alter the position of hyoid or may attach to the walls of the pharynx.

- Middle pharyngeal constrictor: elevates the pharyngeal walls

- Stylopharyngeus: elevates the pharyngeal walls

- Palatopharyngeus: elevates the pharyngeal walls

- Stylohyoid: causes a laryngeal elevation

- Hyoglossus: causes a laryngeal elevation

- Geniohyoid: causes the laryngeal elevation

- Mylohyoid: causes the laryngeal elevation

- Digastric: causes a laryngeal elevation

- Omohyoid: causes laryngeal depression

- Sternohyoid: causes laryngeal depression

Physiologic Variants

Laryngeal Structure/Skeleton

There are gender-related differences that lead to different laryngeal dimensions in males and females. This differences also exist in the angles of the larynx including the thyroid angles (male 95, female 115 degrees). Even with this variation, the larynx shows symmetry when comparing one side to the other. The angles increase when there is a decrease in diameters and dimensions cranial to caudal.

“Broyle’s tendon” is the connective tissue between the thyroid skeleton and the noduli elastici anterior. This also shows a gender-related difference with males averaging 2.9 mm and females 1.8 mm in length. Other absolute differences exist between male and female populations, but the relative dimensions are not significant. The differences can be attributed to the anterior-posterior growing nature of the larynx during puberty. This growth is primarily in the sagittal plane. It is also noted that the thyroid cartilage is noted to be thicker in males as compared to females.

In addition to the size of the laryngeal skeleton, there can be a varying degree of accessory cartilages. These accessory cartilages include the occasional tiny cartilages found within the vocal ligament, interarytenoid, and the critical. Another term for these accessory cartilages is the cartilages of Luschka.

Laryngeal Cavities

There also notes to be some physiologic variation to the laryngeal ventricle. In addition to extending laterally, the laryngeal ventricle may sometimes continue superiorly and anteriorly, forming a saccule beneath the fold.

Nerve Variation

Innervation of the laryngeal structures may also vary. This is seen in the phenomenon called ‘laryngeal synkinesis’. Laryngeal synkinesis is abnormal laryngeal innervation discovered post-trauma to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. In this case, the motor axons of the recurrent laryngeal nerve may regenerate and exit the “parent” recurrent laryngeal nerve. These nerves may follow any of the branching nerves and establish motor connections. The nerve fibers from nearby muscles may sprout toward, and re-innervate the once-paralyzed intrinsic laryngeal muscles. These nerves may include the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, the vagal branches of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles, parasympathetic, sympathetic and intralaryngeal branches. Laryngeal synkinesis differs in classification based upon laryngeal and phonatory patterns.

Variation may also exist the in the branching of the recurrent laryngeal nerve itself. The recurrent laryngeal nerve has been documented to divide into two or more branches prior the entering the larynx via the inferior constrictor muscle in about 40% of RLNs. The anterior branch has been documented to pass either anteriorly or posteriorly to the cricothyroid joint and prior to innervating all intrinsic laryngeal muscles excluding the cricothyroid muscle. The posterior branch typically supplies the arytenoid muscles and posterior cricoarytenoid muscle.

The location of the bifurcation or trifurcation has been documented to range between 0.6 to 4.0 cm from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilages. Although extralaryngeal branching typically occurs above the level of the inferior thyroid artery, it can occur at any point.

The course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve may also differ as a consequence of anatomic distortion by masses or inflammation or because of a vascular anomaly. With an incidence of 0.6%, the recurrent laryngeal nerve may pass directly from the vagus nerve to the larynx in the neck in cases with an atypical right subclavian artery that arises after the left subclavian artery from the aortic arch. This has been referred to as a “nonrecurrent” inferior laryngeal nerve. This occurrence is even less likely with regards to the left side and has only been a document to occur a handful of times.

The recurrent laryngeal nerve may also vary in its relationship with the inferior thyroid artery as the nerve approaches the inferior pole of the thyroid gland. Most commonly (approximately 61%), the recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends posterior to the inferior thyroid artery. The recurrent laryngeal nerve can also ascend anterior (approximately 32.5%) to or in between the branches of the inferior thyroid artery (approximately 6.5%).

As the recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends, it does so within the tracheoesophageal groove. This, however, can vary. It is documented to fall into this groove more often on the left side [77%] as compared to the right side [65%]. Subsequently, the recurrent laryngeal nerve is found to ascend lateral to the trachea more often on the right side [33%] than the left [22%]. In rare circumstances, it ascends anterolateral to the trachea, and as a result, is more exposed and at risk of surgical injury.

Surgical Considerations

Gross Anatomic Considerations

- Based on laryngeal size, there are absolute differences between the dimensions of male and female larynges. However, no significant relative differences exist. Thus, surgery should be based upon the relative size and the utilization of anatomic landmarks.

- An incision is made through the cricothyroid membrane for a cricothyrotomy. This technique is quicker and poses fewer complications than a tracheotomy.

Nerve Considerations

- Monitoring the recurrent laryngeal nerve and superior laryngeal nerve is important in any neck related procedures including thyroid lobectomy or thyroidectomy

- An indirect laryngoscopy is an essential tool in confirming the integrity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve pre and postoperatively.

- Reinnervation is a technique that can be utilized on the abductors and tensors of the vocal folds by using a nerve-muscle pedicle. This can only be considered if the vocal fold is not fixed.

Clinical Significance

Due to is an anatomical relationship with several important structures, the recurrent laryngeal nerve can be affected in various situations. Thyroid masses, mediastinal and lung tumors, as well as cardiovascular lesions, can cause compression or affect the recurrent laryngeal nerve, commonly the left recurrent laryngeal nerve.[8][9]

Additionally, considering the thyroid glands relationship to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal nerve, surgical resection of the thyroid gland can result in injury to both nerves either directly or indirectly.

Consequences of Nerve Injury

- Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve would result in paralysis of all intrinsic muscles of the larynx except the cricothyroid muscle. This would cause vocal cord paralysis.

- Injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve would result in paralysis of the cricothyroid muscle, leading to dysphonia [alteration in sound pitch].

In addition to difficulties with phonation and pitch, laryngeal weakness creates the risk for aspiration.