Introduction

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) allow physicians to evaluate the respiratory function of their patients in many clinical situations and when there are risk factors for lung disease, occupational exposures, and pulmonary toxicity. National guidelines for the measurements and interpretation of PFT are regularly updated, and the most recent guidelines developed by the international joint Task force from the European Respiratory Society and the American Thoracic Society (EUR/ATS) were published in 2022.[1]

The results of the PFTs are affected by the effort of the patient. PFTs do not provide a specific diagnosis; the results should be combined with relevant history, physical exam, and laboratory data to help reach a diagnosis. PFTs also allow physicians to quantify the severity of the pulmonary disease, follow it up over time, and assess its response to treatment.[2]

Procedures

Spirometry

Spirometry is a physiological test that measures the ability to inhale and exhale air relative to time. Spirometry is a diagnostic test of several common respiratory disperses such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It is also instrumental in monitoring the progression of various respiratory disorders. The main results of spirometry are forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume exhaled in the first second (FEV1), and the FEV1/FVC ratio. The procedure of spirometry has 3 phases: 1) maximal inspiration; 2) a “blast” of exhalation; 3) continued complete exhalation to the end of the test. There are within-maneuver acceptability and between-maneuver reproducibility criteria for spirometry (Table 2).

The spirometry procedure is usually performed in a standard sitting position. However, spirometry measurement in the supine position may be indicated in certain neuromuscular disorders. For example, in individuals with spinal cord injury, at the level of T6 and above, the FVC and FEV1 are decreased and become lower in the supine position compared to the upright position suggesting an increased risk of hypoventilation during sleep.[3]

Lung Volume

The measurement of lung volumes includes several important variables, such as functional reserve capacity (FRC), vital capacity (VC), slow vital capacity (SVC), expiratory reserve volume (ERV), and residual volume (RV). The lung volume measurement is very important to detect changes in lung volume independent of effort, especially when FVC is reduced on spirometry.

FRC is the volume of the amount of gas in the lungs at the end of expiration during tidal breathing. FRC is also the sum of ERV and RV. Once FRC has been measured, all other volumes can be calculated.

ERV is the volume of gas maximally exhaled after end-inspiratory tidal breathing. RV is the volume of gas in the airways after a maximal exhalation. VC is the volume of gas expelled from full inspiration to residual volume. The FVC is similar, but the patient exhales at maximal speed and effort.

In addition to RV and ERV, there is a tidal volume (TV) and inspiratory reserve volume (IRV). IRV is the volume of gas that can be maximally inhaled from the end-inspiratory tidal breathing. TV is the volume of gas inhaled or exhaled with each breath at rest. Slow vital capacity (SVC) can be measured as the maximal amount of air exhaled in a relaxed expiration from full inspiration to residual volume; exhalation should be terminated after 15 seconds.[6] The SVC may be a useful measurement when the FVC is reduced, and airway obstruction is present.

Total lung capacity (TLC) is the volume of air in the lungs at the end of maximal inspiration. The sum of RV and VC or FRC and inspiratory capacity (IC) equals TLC, which is the gold standard for diagnosing restrictive lung disease. TLC less than 80% predicted is diagnostic of a restrictive ventilatory defect.[4][5]

There are two methods to measure lung volumes: body plethysmography and gas dilution methods (nitrogen washout and inert gas dilution). The gas dilution method uses an inert gas (poorly soluble in alveolar blood and lung tissues), either nitrogen or helium. The subject breathes a gas mixture until equilibrium is achieved. The volume and mixture of gas exhaled after the equilibrium has been achieved permit the calculation of FRC. In body plethysmography, the subject sits inside a body box and breathes against a shutter valve. FRC is calculated using Boyle Law (at a given temperature, the product of gas volume and pressure is constant). FRC calculated by body plethysmography is usually larger in subjects with obstructive lung disease and air trapping than FRC calculated using gas dilution methods. Body plethysmography is considered the gold standard for lung volume measurement, especially in heterogeneous airflow obstruction, such as in COPD or asthma, where plethysmography is more accurate than helium dilution.[6]

Capacities are the sum of 2 or more volumes and are depicted in Figure 1.

Diffusion Capacity

Diffusion studies the diffusion of gases across the alveolar-capillary membranes. Its measurement uses carbon monoxide (CO) to calculate the pulmonary diffusion capacity. The most common method is the standard single-breath D. It is measured in milliliters per minute per mm Hg.

The factors affecting the D are volume and distribution of ventilation, mixing and diffusion, the composition of the gas, characteristics of the alveolar membrane and lung parenchyma, the volume of alveolar capillary plasma, concentration and binding properties of hemoglobin, and gas tensions in blood entering the alveolar capillaries. A detailed list of factors affecting DLCO is listed in Table 3.

The diffusion capacity depends on multiple factors, and its value should be adjusted. For correct interpretation, specific adjustments should be made for hemoglobin, carboxyhemoglobin, and FiO2. Adjustment for lung volumes is controversial, and further studies are needed.

The DLCO is interpreted in conjunction with spirometry and lung volumes. Table 3 shows the severity classification for DLCO. For example, high DLCO is associated with asthma, obesity, and intrapulmonary hemorrhage. Normal spirometry and lung volumes with low DLCO can be present in pulmonary vascular diseases, early ILD, or emphysema. An obstructive ventilatory defect with low DLCO suggests emphysema or lymphangiomyomatosis.[7][8]

Respiratory Muscle Pressures

The respiratory muscle strength is assessed with maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP) and maximal expiratory pressure (MEP). The MIP reveals the strength of the diaphragm and other inspiratory muscles, whereas the MEP indicates the strength of the abdominal and other expiratory muscles. MIP and MEP are measured three times, and maximal value is reported. For adults 18 to 65 years old, MIP should be lower than -90 cmHO in men and -70 cmHO in women. In adults older than 65, MIP should be less than -65 cmH2O in men and -45 cmH2O in women. MEP should be higher than 140 cmH2O in men and 90 cmH2O in women. MEP less than 60 cmH2O predicts a weak cough and difficulty clearing secretions.

Bronchoprovocation testing

There are several types of bronchoprovocation testing available to assess airway responsiveness. The pharmacologic challenge or exercise challenge are the most common types for bronchoprovocation testing and the accurate diagnosis of asthma. Before initiating the bronchoprovocation testing, several precautions should be taken: (1) The person performing the test should be able to identify the occurrence of severe bronchospasm; (2) a rapid-acting beta-agonist (such as albuterol) should be immediately available; (3) FEV should be insured that has returned to or exceeded to baseline before the patient leaves the pulmonary function laboratory; (4) equipment for resuscitation should also be available and accessible with qualified personnel.

The most commonly used agent for bronchoprovocation is methacholine (acetylcholine derivative) at incremental doses ranging from approximately 0.03 mg/mL to 16 mg/mL. Bronchoprovocation testing is usually performed after obtaining baseline spirometry, using a diluent that is aerosolized via nebulizer for at least one minute, then spirometry is repeated twice. The dose of methacholine is then sequentially increased until a decrease in FEV > 20%. The dose of methacholine is associated with a greater than 20% decrease in FEV1 and is referred to as the provocative dose or PD20. A methacholine PD20 of 8 mg/mL or less is considered a positive bronchoprovocation test. However, a PD20 greater than 16 mg/mL is regarded as a negative test. [9]

Six-minute walk test (6MWT)

Six-minute walk test s a standard test to assess exercise capacity objectively and determine prognosis in many respiratory (such as COPD, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary hypertension) and non-respiratory conditions (such as heart failure).[10][11] The minimal clinically important difference for change in the 6MWT distance of adults is approximately 30 meters.[12] The 6MWT is not designed to be used for home oxygen titration and assessment, and a separate study is recommended to assess the need and dose of supplemental oxygen. Performance of the test requires the presence of a flat, straight corridor 30 m (100 feet) in length, the ability to monitor heart rate and pulse oximetry throughout the test, and if the patient uses supplemental oxygen, to record the flow rate and type of Oxygen device. [10]

Indications

There are multiple indications to obtain PFTs. Table 1 summarizes the most common indications.

PFTs can be physically demanding for patients, and it is recommended to wait one month after an acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction. Other relative contraindications are thoracic/abdominal surgery, brain/eye/ear/otolaryngological surgery, pneumothorax, ascending aortic aneurysm, hemoptysis, pulmonary embolism, severe hypertension (systolic blood pressure greater than 200 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure greater than 120 mm Hg).[13]

The bronchoprovocation testing is mainly indicated for patients with intermittent asthma symptoms and normal baseline spirometry.

Normal and Critical Findings

Normal findings of spirometry are an FEV1/FVC ratio of greater than 0.70 and both FEV1 and FVC above 80% of the predicted value. If lung volumes are performed, TLC above 80% of the predictive value is normal. Diffusion capacity above 75% of the predicted value is also considered normal.

The natural changes in lung function over time are an important indicator of the health status of the lungs. In non-smokers, FEV1 typically decreases by approximately 30 mL per year. Traditionally a 10% change in FEV1 from baseline over a year duration in healthy individuals is considered significant clinically.[1] However, changes in FEV1 and FVC over time depend on patient demographics such as age, sex, and baseline lung function. Therefore, future studies are needed to adjust for these factors.

Interfering Factors

The results of the PFTs might not be accurate if there is a lack of cooperation or poor understanding of instructions from the patient. Also, if the patient has an acute illness or symptom (for example, altered mental status, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal or chest pain, or cough) are likely to have suboptimal results.

Complications

PFTs are safe in general, and there are no complications. There is some potential harm from 4 key factors:

- Maximal pressures generated in the thorax and their impact on abdominal and thoracic organs/tissues

- Large swings in blood pressure cause stress on tissues in the body

- Expansion of the chest wall and lungs

- Spread of infections (e.g., tuberculosis, hepatitis B, HIV)

Contraindications of PFTs are related to those four factors to prevent potential complications like acute coronary syndrome, rupture of aneurysms, and dehiscence of the surgical wound.[13]

Patients with myocardial infarction, unstable heart disease, or stroke within the previous three months should not perform bronchoprovocation testing. In addition, patients with an FEV <70 % of predicted are usually excluded from performing bronchoprovocation testing.[9]

Clinical Significance

The first step in interpreting PFTs is to review the test quality. Once the quality has been assured, comparisons can be made with healthy subjects and abnormal physiological patterns.

Types of Ventilatory Defects (Table 3)

Obstructive Abnormalities

An obstructive defect is a disproportional decrease in maximal airflow from the lung (FEV1) relative to the maximal volume (FVC) that can be displaced from the lung. In practical terms, an FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 0.70 defines an obstructive ventilatory defect. However, other variables such as age, race, and gender affect this cutoff to estimate expected lung function in health.[1] Hence the decrease in FEV1 and FVC are compared to the lower limit of normal (LLN) to identify whether or not the observed result can be expected in otherwise healthy individuals of similar age, sex, and height.

The earliest change associated with an obstruction in small airways is a slowing in the terminal portion of the spirogram (mid-flows). Qualitatively, it is reflected by a concave shape on the flow-volume curve. Quantitatively, proportionally increased the reduction in the instantaneous flow measured after 75% of the FVC has been exhaled (FEF) or FEF. Nevertheless, mid-flow abnormalities are not specific to airflow obstruction, and it is no longer a diagnostic criterion of airflow obstruction.

The FEV1 is used to classify the severity of obstructive lung diseases traditionally based on % predicted values into five levels.[14]

- FEV1 >70% of predicted is mild

- FEV1 60-69% of predicted i is moderate

- FEV1 50-59% of predicted is moderately severe

- FEV1 35-49% of predicted is severe

- FEV1<35% of predicted is very severe

However, this method did not factor in age differences; therefore, it was recently changed to something new called z-score (express, which is defined as how far an observed lung function value is from the predicted value after accounting for sex, age, height, and ancestral factors). The utility of the new proposed cut values of −2, −2.5, −3, and −4 severity-scale systems in clinical practice is not clear yet, as most PFT systems continue to use the old method of reporting FEV1.

For many years the reversibility testing has been administered using a bronchodilator (short-acting beta 2-agonist or anticholinergic agent). An increase in either FEV1 or FVC of >12% and >200 mL is considered a positive bronchodilator response. However, the most recent ERS/ATS interpretation standards recommend that a significant bronchodilator response is defined by an increase in FEV1 or FVC by at least 10 percent of the respective predicted values.[1] A lack of response on spirometry post bronchodilators does not predict a lack of clinical response to bronchodilators. In patients with COPD, the bronchodilator response (manifesting by a significant change in FEV or FVC), but the reversal to normal values of FEV1 or FVC on spirometry makes COPD less likely.[15] This contrasts with asthma, as the response to the bronchodilator test can lead to normal spirometry.

The patient should hold their bronchodilators before the reversibility testing. The duration for holding the inhalers differs based on the type of short or long-acting inhaler. Short-acting inhaled beta-agonists (e.g., albuterol) should be held for at least 4 to 6 hours before spirometry. Long-acting inhalers such as tiotropium should be held for 36 to 48 hours before spirometry.

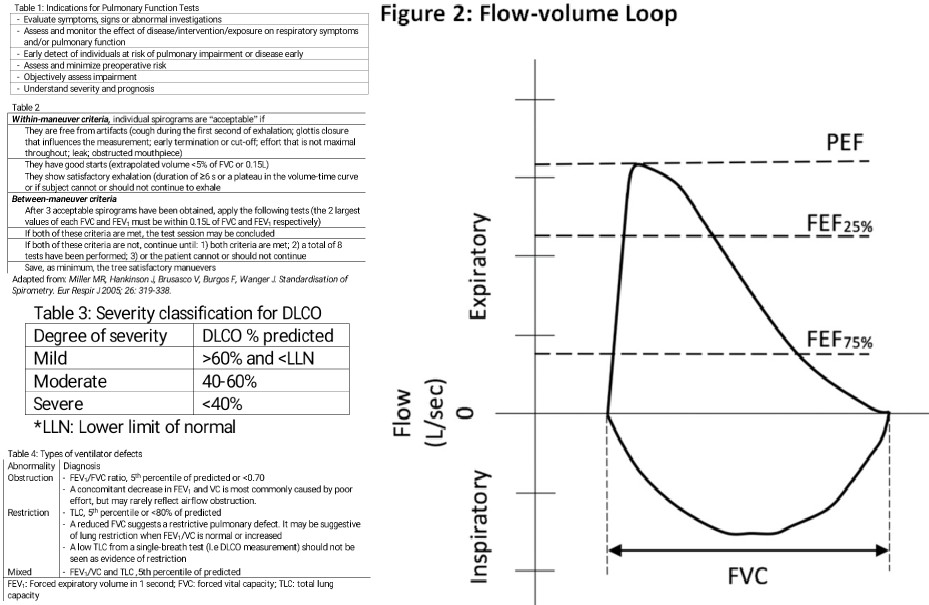

The spirometry procedure includes the measurement of flow volume loops. The maximal flow-volume curves are a great asset for detecting mild airflow obstruction (Figure 2). In each flow-volume loop, there is an inspiratory and expiratory segment.[16] The flow-volume loops (FVL) allow assessment of upper airway obstruction, both variable (e.g., vocal fold paralysis) and fixed types (e.g., tracheal stenosis), and intra- and extrathoracic locations. When the plateau of the FVL occurs in the inspiratory limb, the obstruction is variable and extrathoracic, while when it only occurs in the expiratory FVL limb, the obstruction is variable and intrathoracic. When both limbs are plateaued, then the obstruction is fixed, such as in tracheal stenosis.

Restrictive Abnormalities

Restrictive ventilatory defects are characterized by a normal FEV1/FVC ratio (>0.70) and a reduction in TLC below the fifth percentile or 80% of the predicted value. They can be suspected if the FVC is reduced (less than 80%), FEV1/FVC is increased (0.70), and the flow-volume curve shows a convex shape. Spirometry can only suggest a restrictive defect; lung volumes are necessary to confirm the defect. As mentioned previously, TLC is the gold standard for diagnosing a restrictive defect. The severity of the restrictive defects is based on the FEV1 percentage predicted value, using the same severity scale as obstructive defects.

In patients with kyphoscoliosis, a restrictive ventilatory defect is common on pulmonary function tests. The decline in vital capacity (VC) correlates with the degree of kyphosis. The ventilatory defect manifest by reduced VC and total lung capacity (TLC) with preserved residual volume.

Mixed Abnormalities

These are characterized by obstructive and restrictive defects, diagnosed when both FEV/FVC and TLC are below the five percentile of their predicted values (or FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.70 and TLC less than 80% predicted value). If FEV1/FVC ratio is low and FVC is less than 80% of predicted, but TLC is normal, the patient has an obstructive pattern, and FVC is low due to hyperinflation. If the TLC is low, the patient has a mixed obstructive and restrictive pattern. For mixed defects, spirometry and lung volumes are needed for diagnosis. The severity of the restrictive defects is also based on the FEV percentage predicted value, using the same severity scale as obstructive defects.[13][4]