Continuing Education Activity

Parinaud syndrome is also known as sylvian aqueduct syndrome, dorsal midbrain syndrome, pretectal syndrome, and Koerber-Salus-Elschnig syndrome. Parinaud syndrome is classically described by the triad of impaired upward gaze, convergence retraction nystagmus, and pupillary hyporeflexia. This condition has multiple potential etiologies. Patients may complain of difficulty looking up, blurred near vision, diplopia, oscillopsia, and associated neurological symptoms. Diplopia is present in 65 percent of patients. Treatment is primarily directed at treating the underlying cause before irreversible damage occurs. This activity describes the etiology, evaluation, and management of Parinaud syndrome and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of affected patients.

Objectives:

- Review the causes of Parinaud syndrome.

- Describe the characteristic presentation of Parinaud syndrome.

- Describe the treatment of Parinaud syndrome.

- Parinaud syndrome is best managed by an interprofessional team including neurology and ophthalmology. The key is to make the diagnosis of the primary disorder and manage it. However, some patients with chronic symptoms may need eyelid surgery.

Introduction

French ophthalmologist, Henri Parinaud, first described Parinaud syndrome in the late 1800s. Parinaud described it in a series of case reviews of patients with disturbances of associated eye movements and gaze paralysis. He attributed the cause of this condition to a lesion of the quadrigeminal area. This condition is variously known as the Sylvian aqueduct syndrome, dorsal midbrain syndrome, Pretectal syndrome, and Koerber-Salus-Elschnig syndrome. The original description by Henri Parinaud included upgaze palsy and convergence paralysis. However, the definition of Parinaud syndrome has now been widened to include the triad of upgaze paralysis, convergence retraction nystagmus, and pupillary light-near dissociation. Also, it may sometimes include conjugate downgaze in the primary position and rarely downgaze palsy.[1]

Etiology

The causes of Parinaud syndrome include pineal gland tumors, midbrain infarctions, multiple sclerosis, midbrain hemorrhage, encephalitis, arteriovenous malformations, infections (toxoplasmosis), trauma, obstructive hydrocephalus, and sometimes, tonic-clonic seizures. There have been reports of this condition following brachytherapy instillation. However, the most common causes are a pineal gland tumor and other midbrain pathologies like hemorrhage and infarction. The underlying cause of Parinaud syndrome is also found to vary with age. Neoplastic causes are more common in children and young adults, and vascular causes are more common in the middle-aged and older populations.[2][3][4]

Epidemiology

Parinaud's syndrome usually presents as a sporadic condition. The most common causes are pineal gland tumors and midbrain infarction.[5] Some studies have described that up to 65% of cases are due to primary midbrain lesions like strokes, hemorrhages, and neoplasms and up to 30% of cases were due to Pineal gland tumors causing pressure on the reflex centers in the Quadrigemina(dorsal midbrain).[6]

The classic triad of upgaze paly, convergence retraction nystagmus and pupillary light-near dissociation was seen in about 65% of patients with Parinaud's syndrome.

Pathophysiology

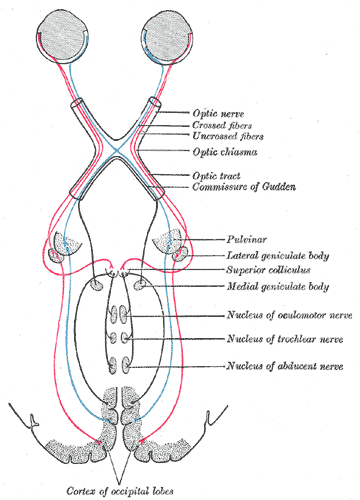

The constellation of signs and symptoms of Parinaud syndrome are caused by compression of the rostral midbrain and pretectum at the level of the superior colliculus.

The characteristic symptom of Parinaud syndrome is limited conjugate upgaze. It occurs because of the involvement of the vertical gaze centers, which are in proximity to the Superior colliculus, with some of the main nuclei being the interstitial nuclei of Cajal and the rostral interstitial nucleus of the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (riMLF). Downgaze is classically preserved, but the reason for this is not entirely explained. It has been suggested that the pathways for downward gaze are directed medially from the rostral interstitial nucleus of the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF); whereas, the fibers for upward gaze are directed laterally from the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus and decussate in the posterior commissure. This makes them more susceptible to the pressure effect of space occupying lesions. However, a condition called Reverse Parinaud syndrome has also been described. In this condition, there is downgaze palsy instead of upgaze palsy, and the patient presents with the combination of downgaze palsy with convergence weakness and pupillary light-near dissociation. This is an extremely rare condition with very few reported cases.

Another component of the triad of Parinaud syndrome is convergence- retraction nystagmus which is characterized by an irregular, jerky nystagmus, associated with convergence and retraction of both eyes, especially on attempted upgaze. It has been postulated that convergence retraction nystagmus is caused by damage to the supranuclear fibers, which have an inhibitory effect on the midbrain convergence or divergence neurons. This results in sustained discharge from the medial rectus and other extraocular muscles. Convergence retraction nystagmus is considered a highly localizing sign, pointing to a lesion of the dorsal midbrain.

The third component of the Parinaud syndrome triad is pupillary involvement. There is poor pupillary constriction to light but preserved constriction with convergence. The pupillary light reflex fibers synapse at the pretectal nucleus and the pass to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus of the same side and the contralateral side through the posterior commissure, making them susceptible to external compressive effects of mass lesions. It is thought that the fibers for the near reflex are located more ventrally. Thus they are spared in Parinaud syndrome, which is a dorsal midbrain syndrome.

Patients may also present with lid retraction in the primary position, which is called the Collier sign. The cause is thought to be due to damage to the levator inhibitory fibers at the posterior commissure.

History and Physical

Parinaud syndrome is classically described by the triad of upgaze palsy, convergence retraction nystagmus, and pupillary hyporeflexia.[7] Patients may complain of difficulty looking up, blurred near vision, diplopia, oscillopsia, and there may be associated neurological symptoms. Many studies have described diplopia as the most common symptom. It is seen in 65% of patients. Diplopia may be caused either by skew deviation or associated fourth nerve palsy. Vertical diplopia is classically seen and can be very disabling to the patient. Some patients may also a complaint of blurred vision, and it could be due to accommodation spasm. For many, the most incapacitating symptom is the inability to elevate the eyes, often causing a compensatory chin up position.

The signs of Parinaud syndrome include:

- Paralysis of vertical gaze, especially conjugate upgaze palsy. Sometimes there may be combined upgaze and downgaze palsy, and rarely there could be only downgaze palsy. The vestibule-ocular reflex is classically spared

- Convergence retraction nystagmus, which is best elicited using a downwardly moving optokinetic nystagmus drum.[8] Attempted up-gaze triggers an episodic refractory jerking of the eyes

- Loss of pupillary light reflexes (Light Near-dissociation)

- Loss of convergence is seen in less than a quarter of patients

- Upper eyelid retraction (Collier's "tucked lid" sign) seen in approximately 40% of patients

- There could be a conjugate downgaze in the primary position, called the "setting sun" sign

Evaluation

A thorough neurological examination is indicated in all patients. Visual acuity examination, visual fields, color vision, pupillary examination, and fundoscopy are indicated. Because of the wide variety of causes of this condition, a thorough workup including neuroimaging is mandatory to discover the underlying cause.[9] Infection screening, serum protein electrophoresis, and thyroid function tests may also be done. Other investigations which may be done include cerebrospinal fluid studies, serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and nerve conduction studies.

Treatment / Management

Treatment is primarily directed toward the underlying cause. Symptoms may be completely reversed in patients with early hydrocephalus. The aim of treatment is, therefore, to treat the underlying condition urgently before permanent damage occurs.[10] Persistent upgaze palsies may be corrected surgically. The surgical options include inferior rectus recession, superior rectus resection, and superior transposition of medial and lateral rectus muscles. All these procedures improve upgaze position and abnormal head position and ultimately improve the severity of retraction nystagmus. Visual training and tracking exercises are another options, which can also be used in patients with persistent gaze palsies.

Differential Diagnosis

- Compression by mass in the pineal region

- Dilation of the third ventricle

- Lesions of posterior commissure and MRF

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Parinaud syndrome is best managed by an interprofessional team including neurology and ophthalmology nurses. The key is to make the diagnosis of the primary disorder and manage it. However, some patients with chronic symptoms may need eyelid surgery.

The outcomes for patients with parinaud syndrome depend on the cause.