Introduction

Infectious mononucleosis (IM), caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), is an extremely common disease process in the United States and around the world. Nearly 90 to 95 percent of the world’s adult population has evidence of EBV infection through seroconversion.[1] Though often subclinical in the young pediatric population, clinical symptomatology is very common in adolescent and young adult aged patients. Commonly, symptomatic patients present with malaise, fatigue, fever, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, and lymphadenopathy. Diagnostically, this creates a dilemma due to the potential for many other causes for these symptoms.

Several laboratory tests have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of IM. Currently, serum testing for EBV-specific antibodies is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, but rapid results are usually not obtainable. Because of this time delay, several other testing modules have been created with the most widely used test being the mononuclear spot test or, monospot test.

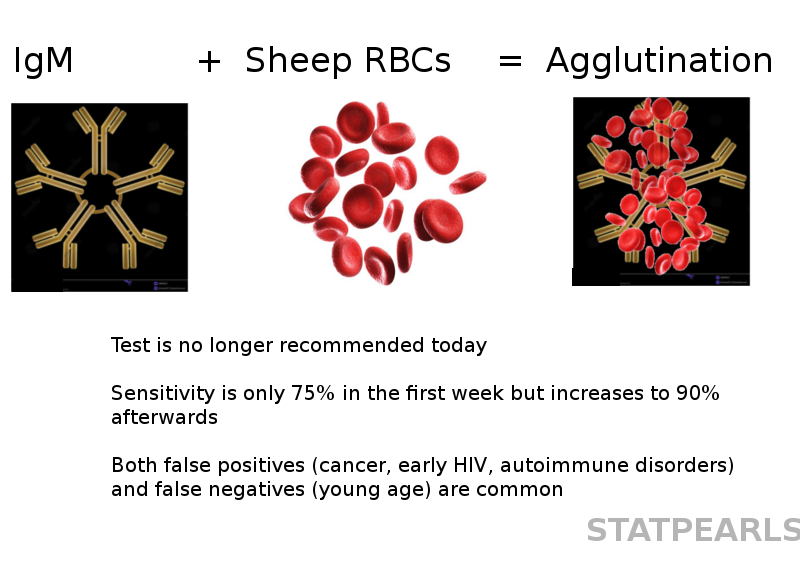

The basis of the monospot test is blood agglutination, much like the Paul-Bunnell test which was developed prior to the monospot test.[2] The monospot test is a latex agglutination test which utilizes equine erythrocytes as the primary substrate and tests for specific heterophile antibodies produced by the human immune system in response to EBV infection.[3][4][2] When these specific antibodies are present in the patient's blood specimen, exposure to equine erythrocytes will lead to clumping of the sample, thus signaling a positive agglutination reaction.[4] This reaction is considered a positive test and therefore a diagnostic confirmation of the clinically suspected IM.

Though the monospot test is considered to be a very specific test, the sensitivity falls in the range of 70 to 90% and is particularly weak among children under the age of four years old.[5][3] Because of this low sensitivity, the Center for Disease Control does not recommend the monospot test for the diagnosis of clinical infectious mononucleosis.

Specimen Collection

A sample of the patient’s blood is required to perform a monospot test. This sample is obtainable intravenously or a simple fingerstick. In most commercially available kits, a small amount of blood is placed in the sample collection window.[3] The 'result' time may vary somewhat between individual testing kits, but generally, results are available within 5 to 10 minutes. The results field of the kit will typically have a control indicator as well as a test indicator that reads as either positive or negative.

Procedures

The only procedure required is a simple fingerstick or intravenous blood sample collection.

Indications

The use of the monospot test may be indicated in a patient presenting with complaints that are consistent with IM. Signs and symptoms of IM include sore throat, fever, malaise, tonsillitis, lymphadenopathy, and fatigue. Because of the significant overlap of symptoms with other common viral illnesses, testing is usually indicated for patients who have a prolonged course of symptomatology which is not consistent with typical upper respiratory viral infections. Further, because peak heterophile antibody levels are seen between 2 to 6 weeks from infection, testing too early in the disease process may lead to increased rates of false negative testing.[6]

The monospot test is not indicated for patients under the age of four years old as false-negative test results are unacceptably high. Sensitivity rates for this age group range from 27 to 76%.[3][7]. In the population of adults 30 years and older, the rate of IM is exceeding low due to previous exposure to EBV and therefore, testing is generally not indicated in this population.

Potential Diagnosis

The benefit to the monospot test is the rapid identification of the presence of heterophile antibodies and thus, the rapid diagnosis of IM. Although IM is a self-limiting disease process, prompt diagnosis is essential to minimize complications and prevent unnecessary treatments. IM may lead to the development of splenomegaly which can increase the chances of splenic rupture and hemorrhage. Often, individuals with diagnosed IM will be held out of contact sports to decrease the potential of splenic rupture.[8]

In addition to the minimization of complications, rapid disease detection may lead to reduced usage of antibiotics. The symptoms of IM are very similar to pharyngitis and tonsillitis caused by Streptococcal species. Many patients may be treated unnecessarily with antibiotic therapy for IM, and the rapid identification of the causative organism may help to bolster better antibiotic stewardship as well as prevent potential complications of antibiotic treatment such as rash, diarrhea, and allergic reaction.

Normal and Critical Findings

The monospot test is meant to deliver simplistic results and therefore is either positive or negative. Positive results indicate the presence of heterophile antibodies in a patient with symptomatology consistent with IM. A negative result is intended to indicate the lack of heterophile antibodies and should lead clinicians to pursue other causes of the patient’s symptomatology.

Interfering Factors

There are multiple interfering factors with the monospot test, leading to significantly decreased levels of sensitivity and to decreased specificity as well.

Regarding the sensitivity of the test, there are many factors that contribute to high rates of false negative testing. The first involved is patient age. It has been demonstrated that children four years old and younger have unacceptably high false negative findings when compared to EBV-specific antibody testing. In one study, children under the age of 4 who showed evidence of disease through EBV-specific antibody testing had agglutination testing sensitivity rates between 27 to 76%.[3][7]

Although sensitivity rates have been reported anywhere between 70% and 90%, these numbers appear to be somewhat dependent on the time at which the blood sample is taken. Heterophile antibodies are present in peak concentrations between 2 and 6 weeks of disease.[6] If testing occurs too early in the disease course, it may lead to further decreased sensitivity of the monospot test as concentrations of heterophile antibodies must reach a threshold level in the serum to be detected by the agglutination process. High rates of false negatives have been identified with patients tested before 1-2 weeks of symptomatic onset. Sensitivity rates peak at about 6 weeks of symptoms which may necessitate repeat testing in patients who continue to have symptoms, despite negative test results during previous health care encounters.[6]

In addition to varying sensitivity rates of detecting heterophile positive IM, the monospot test is unable to identify cases of heterophile negative IM. Approximately 90% of IM cases are caused by EBV.[9] In cases of heterophile negative IM, the lack of agglutination causing antibodies will lead to a negative monospot result, despite persistent symptoms. Since EBV is not the cause, the specific causative agent must be identified, usually with serum testing.

The specificity of the monospot test is considered to be quite reliable and has a specificity rate between 95 to 100%.[5] Despite high rates of specificity, there have been some case reports detailing false positives from other disease processes such as Cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, lupus, lymphoma, rubella, and herpes simplex virus. It is also noteworthy that low levels of heterophile antibodies may persist at low levels for 9 months to 1 year after resolution of symptoms.[10]

Complications

Complications from the testing process are very rare. Because testing requires obtaining a blood sample, complications are usually related to pain and bruising at the site of needle insertion and on extremely rare occasions, infection. In the case of an intravenous blood sample, thrombophlebitis may occur as may persistent bleeding at the site, though these are extremely uncommon.

Patient Safety and Education

It is important for patients to recognize the limitations of the monospot test, particularly its lower rates of sensitivity. If a patient undergoes monospot testing, particularly early on in the disease course, it is crucial that they continue to follow with their health care provider, especially if symptoms persist. If IM is under suspicion as the cause of symptoms and monospot test has been negative, then it is important to discuss the utility of EBV specific antibody testing.

Clinical Significance

Infectious mononucleosis is a rather common disease that is seen primarily in patients ages 10 to 30 years old. Its symptoms, which include sore throat, fever, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy overlap with many other common disease processes. Although the disease is treated with supportive care only, diagnosis is vital to initiate prevention of complications and ineffective or potentially dangerous treatments may be avoided.

The monospot test is a particularly common test for the rapid detection of IM. Results are obtainable within 5 to 10 minutes, and the cost of the test is relatively inexpensive, thus making it a very common testing modality in clinics and urgent care settings. However, because of the test’s limited sensitivity, the Center for Disease Control does not endorse this modality of testing for general use or confirmation of EBV.

It is incumbent upon the practitioner to understand the appropriate use of the monospot test and the limitations inherent within the test, particularly with regards to its sensitivity. In patients between the ages of 10 and 30 years old who have a constellation of symptoms consistent with IM, a positive monospot test may help to help to clarify the diagnosis of IM further, though EBV specific antibody testing should be a strong consideration.

In patients presenting with Infectious mononucleosis-like symptoms who have a negative monospot test, false negative test results should be considered, especially if patient testing occurred within the first 1 to 2 weeks of symptoms. It is crucial for the health care provider to consider EBV specific antibody testing or close follow up and repeat testing, depending on what resources are available.

As with any diagnostic testing modality, one must understand the limitations of the test and the appropriate population in which to initiate testing. Although it is a rapid and inexpensive test, there are significant concerns and limitations, particularly with the sensitivity of the test. It should be utilized as a diagnostic aid in patients older than 4 years of age who present with symptoms that are clinically consistent with IM. However, EBV-specific antibody testing is the recommendation for actual confirmation of the diagnosis of IM, due to EBV.