Continuing Education Activity

The intrauterine device is one of the most effective contraceptive methods available, with failure rates comparable to certain forms of sterilization. Intrauterine devices offer numerous advantages, including high efficacy, ease of use, reversibility, and excellent patient satisfaction, particularly for those seeking long-term contraception with cost-effectiveness. There are 2 types of intrauterine devices—copper-containing and levonorgestrel-releasing devices. Although both these devices are indicated for contraception, each type has specific indications based on its unique properties and the specific goals of the patient. Intrauterine devices are primarily placed for nonpregnant women seeking long-term protection against pregnancy. The highest-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine device is also approved for treating menorrhagia and providing endometrial protection during hormone replacement therapy.

Similarly, there are specific indications for intrauterine device removal. The primary indication for removal is the patient's preference for any reason, including desire for pregnancy, irregular bleeding pattern, heavy vaginal bleeding, and pain or discomfort, which may represent malposition of the device. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications, risks, and benefits of intrauterine device placement and removal. Participants also explore best practices for ensuring patient safety and satisfaction, highlighting the collaborative role of the interprofessional team in delivering optimal care for patients undergoing intrauterine device placement and removal procedures.

Objectives:

Identify the indications and contraindications for intrauterine device placement and removal.

Determine the necessary equipment, personnel, preparation, and techniques for intrauterine device placement and removal.

Assess patients thoroughly for complications of intrauterine device placement and removal.

Implement interprofessional team strategies to enhance care coordination for intrauterine device placement and removal, optimizing clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Introduction

The intrauterine device (IUD) is one of the most effective contraception options available today, with failure rates as low as certain sterilization methods.[1] In the United States, 2 types of IUDs currently available—the copper-containing IUD and levonorgestrel-containing IUD, which have similar rates of preventing pregnancy, with failure rates of 0.08% and 0.02%, respectively. These devices are more than 99% effective in preventing pregnancy.[2] Additional benefits of IUDs include efficacy, ease of use, reversible nature, and patient satisfaction, especially for women seeking long-term use and cost-effectiveness.[3]

In the United States, the use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) has increased since 1995. This use has continued to rise annually, with 14% of females using contraception opting for LARC methods.[1] With the increased use of LARC, there has been a significant decrease in the number of unplanned pregnancies.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

All IUDs currently available in the United States are T-shaped, with the top of the T intended to rest across the top of the endometrial cavity. IUDs are between 28 and 32 mm wide and 30 to 36 mm long. Uterine width traditionally has been assumed to be adequate in all patients; however, recent ultrasound studies have indicated that cavity width in nulliparous women may be narrower than device width.[4] Therefore, it is essential to consider the available IUD options when counseling patients. The smallest IUDs are 28 mm wide and 30 mm long and are best suited for nulliparous or younger women.

When performing IUD placement and removal, the primary anatomical landmarks to be identified are the cervix and uterus. The uterus should be evaluated during a bimanual pelvic examination to assess its size, shape, position, and any anatomical abnormalities.[5] The cervix is identified during the speculum examination.[5]

Contraindications

Given the 2 classes of IUDs, specific contraindications exist for each type of IUD. However, there are also universal contraindications that are specific to both types.

Universal contraindications for the use of IUDs include the following:

- Pregnancy or suspected pregnancy

- Sexually transmitted infection at the time of IUD insertion, including cervicitis, vaginitis, or any other lower genital tract infection

- Congenital uterine abnormality that distorts the shape of the uterine cavity, making insertion difficult

- Acute pelvic inflammatory disease

- History of pelvic inflammatory disease, unless a subsequent successful intrauterine pregnancy has occurred

- History of septic abortion or history of postpartum endometritis within the last 3 months

- Confirmed or suspicion of uterine or cervical malignancy or neoplasia

- Abnormal uterine bleeding of unknown origin

- Any condition that increases the risk of pelvic infection

- History of previously inserted IUD that has not been removed

- Hypersensitivity to any component of the device [6]

Specific levonorgestrel-releasing IUD contraindications are as follows:

- Confirmed or suspicion of breast malignancy or other progestin-sensitive cancer

- Liver tumors, benign or malignant

- Acute liver disease [6]

For the copper IUD, additional contraindications include the following:

- Wilson disease

- Sensitivity to copper [6]

Equipment

Regardless of the type of IUD inserted or removed, the equipment is essentially the same. The equipment required to perform IUD placement includes the following:

- Two pairs of examination gloves, including a pair of sterile gloves

- Vaginal speculum

- Antiseptic solution with applicators, such as swabs or cotton balls

- Sterile uterine sound

- Sterile cervical tenaculum

- Sterile IUD package with IUD

- Long-handled scissors

- Anesthesia with appropriate materials if planning to perform a paracervical block

The equipment required to remove the IUD includes gloves, a speculum, sterile ring forceps, and a cytobrush.[5]

Personnel

For a successful IUD placement or removal, the healthcare professional must be proficient in using the specific IUD inserters and comfortable with the indicated procedure. The manufacturers of the various IUDs provide training for clinicians and have extensive resources available through their respective websites. If an inexperienced healthcare professional places the device, there is a risk of displacement and possible uterine perforation.[7] Having at least 1 other medical team member present is optimal to help handle the necessary materials.

Preparation

The first step in setting a patient up for success with an IUD is to provide counseling about the available contraceptive options. Patients should be informed that all forms of LARC, including IUDs and subdermal implants, are highly effective in preventing pregnancy, with efficacy comparable to that of tubal ligation and vasectomy.[8] Strong recommendations support the use of LARC as a first-line option for preventing teenage pregnancies, as IUDs are safe to use in this age group.[9] The Contraceptive CHOICE project has studied the use of LARC and promoted its use by increasing patients' knowledge and acceptability of this form of contraception and removing financial barriers by providing the devices at no cost.[10] By removing these barriers, researchers found that almost two-thirds of the women screened chose LARC options, including both IUDs and subdermal implants.[10] All patients who do not have any contraindications to IUDs should be counseled on the benefits of these devices. Ultimately, it is the patient's choice as to what form of contraception is most beneficial for her. Once a decision is made, the clinic should facilitate the process by ordering the device and ensuring insurance coverage or obtaining prior authorization for the device and its placement.

Before beginning the IUD placement procedure, it is crucial to confirm a negative pregnancy test. First, there is the quick start method, which allows for same-day counseling and insertion, improves the rate of patient follow-through, and decreases the rate of unintended pregnancies.[11] However, this is not always an option when the clinician is unable to confirm a negative pregnancy test due to recent unprotected sex without a current form of birth control. For a pregnancy test to be accurate, one of the following criteria must be met:

- Less than 7 days after the start of regular menses

- No sexual intercourse since the start of the last menstrual period

- Consistently using another form of contraception reliably

- Less than 7 days after spontaneous or induced abortion

- Four weeks or less postpartum

- Fully or nearly fully breastfeeding and amenorrheic, and less than 6 months postpartum [12]

If these criteria are not met, it is an acceptable practice to bridge the patient with a non-implantable form of contraception, such as oral contraceptives, vaginal rings, transdermal patches, condoms, or medroxyprogesterone acetate injections.[10] If the patient still desires LARC insertion after starting one of these bridging methods, a repeat pregnancy test may be conducted in 3 to 4 weeks. If the result is negative, the patient may undergo LARC placement.[10] For copper IUD placement, the prior method of contraception used does not need to be continued, as the copper IUD is effective immediately. However, if the levonorgestrel IUD is not placed within 7 days of the start of menses, an additional form of contraception should be used for 7 days.[12]

In addition, based on the patient's sexual history, screening for sexually transmitted infections should also be conducted. Women who have not been screened for sexually transmitted infections should be screened at the time of IUD insertion if indicated by guidelines; however, this should not delay the insertion of the device.[13] If a patient's test is positive for an infection after IUD insertion, the patient should be treated with antibiotics, and the IUD should remain in place.[13] There is a small risk, approximately 0.1%, of progression to pelvic inflammatory disease if patients have an infection at the time of insertion. However, the device should not be removed.[14] If a patient is noted to have purulent cervical discharge or a physical examination consistent with an active infection, the IUD insertion should be postponed, and the patient should be treated.[6]

Once counseling is complete and a negative pregnancy test is confirmed, it is necessary to obtain informed consent. The risks, benefits, and adverse effects of the procedure must be explained to the patient. Risks associated with IUD insertion include pain at the time of insertion; malposition; uterine perforation, which may necessitate surgery; unintended pregnancy; infection; bleeding at the site of insertion; possible expulsion, which may go unnoticed and lead to unintended pregnancy; and alterations in a patient's monthly bleeding pattern. In addition, if pregnancy does occur with an IUD in place, there is a higher risk of ectopic pregnancy or septic abortion.[15] When comparing the copper IUD with the levonorgestrel IUD, there are key differences in the bleeding pattern changes. The copper IUD typically causes menses to become heavier and occasionally longer.[16] Conversely, the levonorgestrel IUD leads to lighter menses and often complete cessation of menstrual bleeding because of the inhibitory action of progesterone on the endometrium.[17] This effect can also be observed with the lower dose levonorgestrel IUDs. However, there is a small percentage of patients who develop irregular bleeding or spotting with lower progesterone levels.[18][19]

IUD insertion is acutely painful, especially for nulliparous women, which is the primary reason women avoid IUDs and elect less effective contraceptive methods.[20][21] Currently, there is some discussion regarding which pain control methods are most appropriate and effective before and during the procedure. Starting with oral pain medications, researchers have looked at various nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including ibuprofen, ketorolac, naproxen, and tramadol, and found some benefits to prescribing ketorolac before insertion.[21] The use of misoprostol to help with cervical dilation and insertion has been studied in nulliparous patients, but no benefit was noted with its routine use. In fact, it was deemed detrimental because it delayed the insertion process.[17] However, in cases of previously difficult or failed insertions, misoprostol may be helpful.[17] Nitroprusside was also studied as a possible option to help with pain control, although the minimal benefit was observed.[21]

The use of paracervical blocks has been studied both for IUD insertion and other cervical procedures. There is conflicting evidence over using these blocks for routine IUD insertion.[21] Evidence indicates that buffered 1% lidocaine blocks work better compared to nonbuffered lidocaine for pain during uterine sounding and IUD placement. These blocks are placed at the 4 and 8 o'clock positions in nulliparous patients.[22] However, studies have shown that this method may not be as effective as other pain control options, including topical anesthetic creams.[20][21] Topical anesthetic creams and gels have demonstrated effective pain management for IUD insertion. Studies show that using topical lidocaine plus prilocaine 5% cream can lead to significantly superior pain reduction compared to a lidocaine paracervical block, ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, tramadol, nitroprusside, and misoprostol.[20][21] When applied to the genital mucosa, lidocaine plus prilocaine was the most effective pain medication for tenaculum placement, IUD insertion, and post-insertion pain.[21]

Technique or Treatment

After deciding with a patient that an IUD placement is the best contraceptive choice, the procedure is as follows:

- Confirm a negative pregnancy test.

- Obtain informed consent.

- Position the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position.

- With nonsterile gloves, perform a bimanual examination to determine whether the uterus is anteverted or retroverted.

- Insert speculum vaginally to identify the cervix.

- Cleanse the cervix and vaginal fornices with an antiseptic solution, typically povidone-iodine. If the patient has an iodine or shellfish allergy, use chlorhexidine gluconate.

- At this time, consider paracervical block placement or application of the anesthetic gel, as discussed above.

- Switch to sterile gloves. Using a sterile single-tooth tenaculum, grasp the anterior lip of the cervix and apply gentle traction to straighten the cervical canal and uterine cavity. If the uterus is retroverted, grasping the posterior lip of the cervix may be beneficial.

- Using a sterile uterine sound, determine the depth of the uterine cavity, typically between 6 and 9 cm. If the depth is less than 6 cm, the IUD should not be placed. If there is difficulty in inserting the uterine sound, cervical dilators may be necessary. In this case, a paracervical block is recommended.

- Once uterine depth is determined, follow manufacturer instructions for inserting the specific IUD.

- Once the IUD is inserted, cut the strings to 3 to 4 cm with sharp scissors; note this length in the patient's chart.

- Remove the tenaculum, ensuring no bleeding from the tenaculum site, and remove the speculum.

- Schedule a follow-up visit in 4 to 6 weeks for an IUD string check to ensure proper placement.[5]

For IUD removal, the steps are as follows:

- Obtain informed consent.

- Position the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position.

- With gloved hands, insert the speculum into the vagina and identify the cervix and IUD strings. If the IUD strings are not immediately identified, twirl a cytobrush in the cervical os to help identify strings.

- Grasp the IUD strings with ring forceps.

- Place gentle traction on the IUD strings and remove the device from the uterine cavity.

- Ensure that the IUD is intact, and no portions are missing.[5]

If the patient desires further contraception with a new IUD, it is permissible to remove an old device and insert a new one on the same day.

Complications

Complications with IUDs occur in fewer than 1% of women.[20] When counseling patients about the risks associated with the insertion of IUDs, it is important to realize that specific factors may contribute to a poor or unexpected outcome. Given their individual histories, patients should be counseled regarding their particular risks.

A study investigated the ability to predict complications based on numerous characteristics of patients and healthcare professionals.[7] Less experienced healthcare professionals placing the IUD and women who had never had a vaginal delivery were found to be more likely to have a difficult insertion or a failed IUD insertion. Issues with cervical dilatation and bradycardia or vasovagal symptoms were more common in nulliparous women, likely due to cervical manipulation. Older women also had issues with appropriate cervical dilatation. In challenging cases, clinician expertise and ability to manage complications were critical in preventing adverse outcomes.[7]

There are a few complications associated with IUDs. The most common complication is displacement or accidental removal of the IUD after insertion, typically occurring within the first 3 months of insertion.[23] There is also an increased risk of expulsion if placed after vaginal delivery or an abortion.[24][25] However, the benefit to placing IUDs in patients immediately postpartum is that patients do not always follow up for a postpartum visit and contraception, putting them at risk of unwanted pregnancy.[24]

The most concerning complication for a patient is unintended pregnancy. Although becoming pregnant with an IUD is exceedingly rare, this can happen in a small percentage of patients. The percentage of patients who become pregnant with the copper IUD is approximately 0.6%, and for 20 mg levonorgestrel IUD, the rate is approximately 0.2%.[8]

There is a risk of uterine perforation during IUD insertion. Data regarding the perforation rate are inconsistent, as initial perforations may go undetected during the procedure.[26] Some estimates report an occurrence of approximately 1 in every 1000 insertions. Some data indicate that the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD has a slightly higher risk of uterine perforation compared to the copper IUD. However, the study reporting this finding was placing the largest levonorgestrel device.[26] Perforation rates appear higher with early postpartum IUD placement.[27]

Perforation can be complete or partial, with the IUD either fully entering the abdominal cavity or penetrating the uterine wall to varying extents. Complete perforation often causes severe abdominal pain. The device is commonly found in the pouch of Douglas but may migrate within the abdominal cavity, attaching to organs, the bowel, the mesentery, or the omentum, potentially causing further perforations or obstructions. Although quite rare, complete perforation is a life-threatening condition requiring immediate surgical intervention.[28][29]

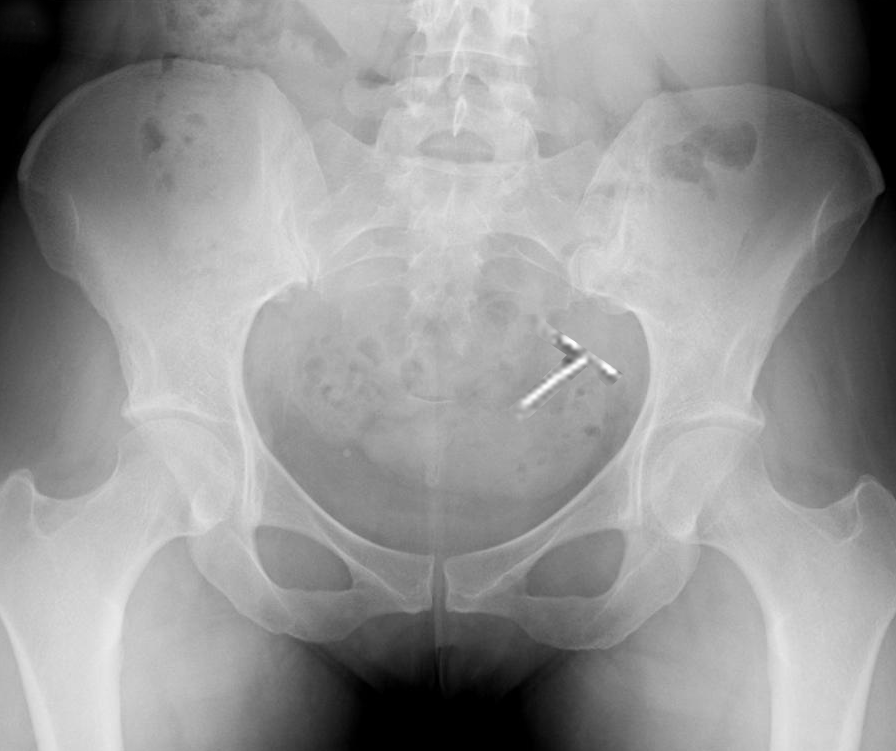

More common complications associated with IUDs include malpositioned IUDs that do not perforate the myometrium, along with dysmenorrhea and amenorrhea (see Image. Plain Radiograph Showing Intrauterine Device Malposition).[30] Risk factors for malpositioning include obesity, a history of uterine rupture or window, and copper IUD placement.[31] Malpositioned IUDs are often located in the lower uterus, potentially causing abnormal bleeding, pain, and an increased risk of pregnancy. Although not all malpositioned IUDs require removal, removal is generally recommended due to the potential loss of contraceptive efficacy. Reduced efficacy is considered greater with malpositioned copper IUDs than with levonorgestrel-releasing devices.

A transvaginal ultrasound or, less commonly, a computed tomography scan can accurately diagnose IUD malposition (see Image. Sonographic Evaluation of the Uterus Demonstrating a Malpositioned Intrauterine Device). If the IUD has partially perforated the myometrium (become embedded) and the strings are visible, removal by pulling the strings should be attempted. If the IUD is not easily removed, then removal under anesthesia with hysteroscopy is generally indicated.

With both insertion and removal of IUDs, there is a risk of vasovagal symptoms and associated bradycardia that may occur when manipulating the cervix. Affected patients should be managed symptomatically. These symptoms are more likely to occur in nulliparous women or women who perceive greater pain at the time of insertion or removal.[32]

Levonorgestrel-containing IUDs can very rarely be associated with acute liver injury; hence, they are contraindicated in women with underlying hepatic injury or tumors.[33] However, the association between liver injury and progestins is not absolute, and the 2024 United States Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use do not recommend routine screening for elevated liver enzymes, given the rarity of undiagnosed disease.[34]

Clinical Significance

As noted, 2 types of IUDs are available in the United States, which include copper-containing and levonorgestrel-containing devices. These devices have different methods of action to prevent pregnancy. The copper IUD prevents sperm motility and viability within the uterine cavity by causing a localized cytotoxic inflammatory response.[35] Given this mechanism, copper IUDs are also a highly effective form of emergency contraception if placed within 5 days of unprotected intercourse.[35] The levonorgestrel-containing IUDs work using progesterone to suppress the growth of the endometrium. The endometrium becomes insensitive to estradiol produced by the ovary.[36] In addition, levonorgestrel thickens the consistency of the cervical mucus, which prevents pregnancy by inhibiting the motility of the sperm.[36] Due to the efficacy, reliability, and reversible nature of these devices, IUDs are an excellent choice for women to prevent pregnancy. Higher-dose levonorgestrel-containing IUDs are also effective in treating menorrhagia and providing endometrium protection during hormone replacement therapy.

Access to various forms of LARC has significantly improved in recent years. However, some barriers remain, especially for nulliparous women and adolescents. Many healthcare professionals remain insufficiently educated on the use of LARC in nulliparous patients, including adolescents. Evidence suggests that these contraceptive methods should be encouraged in these populations because of their reversibility, effectiveness, and high levels of patient satisfaction. The barriers that remain for adolescents and nulliparous women include unfamiliarity or discomfort with the IUD, the initial cost of the device and insertion, lack of parental acceptance, and unfamiliarity of the clinician providing the consultation. However, research has shown that when patients are thoroughly educated about available contraceptive options without concerns about cost, 67% of women choose a form of LARC, with 56% selecting an IUD.[10] In addition, pain is another primary barrier to women choosing LARC and IUDs specifically. Better pain control promotes IUD use, lowering unwanted and unplanned pregnancies and decreasing abortion rates.[20][21]

Healthcare professionals must use evidence-based pain control measures during IUD insertion and stay informed on guidelines to improve patient access to essential care. Earlier studies suggesting that nulliparous women face a higher risk of pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility with IUD use have been refuted. Current evidence confirms that IUDs are safe for nulliparous women.[37] Leading medical organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society for Family Planning, endorse the use of LARC, such as IUDs, in adolescents.[9] Data indicate no significant difficulty in inserting IUDs in nulliparous women, with a success rate exceeding 96%, comparable to that of parous women.[38] For added ease, smaller-diameter levonorgestrel IUDs may be particularly advantageous in nulliparous patients.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimizing IUD placement and removal requires a multidisciplinary approach involving clinicians, advanced practitioners, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers. Key considerations related to skills, strategy, ethics, responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and care coordination can improve patient-centered care, outcomes, safety, and team performance.

Clinicians and advanced practitioners require proficiency in IUD placement and removal techniques, including managing complications, such as embedded devices and uterine perforation. Nurses are essential in patient education, screening for contraindications, and providing pre- and post-procedure care. They also assist during procedures and recognize early signs of complications. Pharmacists provide medication counseling for pain management and ensure access to hormonal IUDs through inventory management and insurance coordination.

Patient-centered counseling, clear team role delineation, and streamlined workflows can optimize care. All team members should be trained in emergency procedures to address adverse events such as syncope, vasovagal reactions, or uterine perforation. Regular team debriefings and training improve procedural efficiency and reinforce best practices. A collaborative, well-structured approach involving diverse healthcare professionals ensures that IUD placement and removal are safe and effective while optimizing the healthcare team's performance.