Introduction

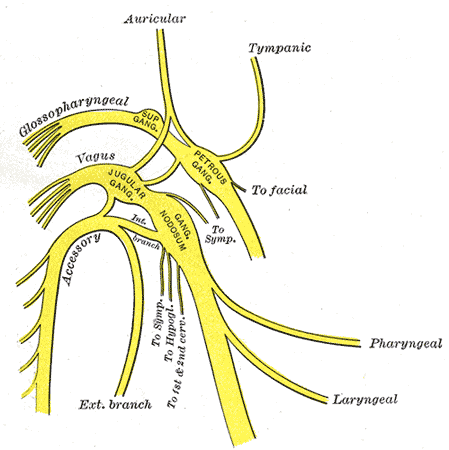

The hypoglossal nerve is the 12th cranial nerve (CN XII). It is mainly an efferent nerve for the tongue musculature. The nerve originates from the medulla and travels caudally and dorsally to the tongue (see Image. The Hypoglossal Nerve).

Structure and Function

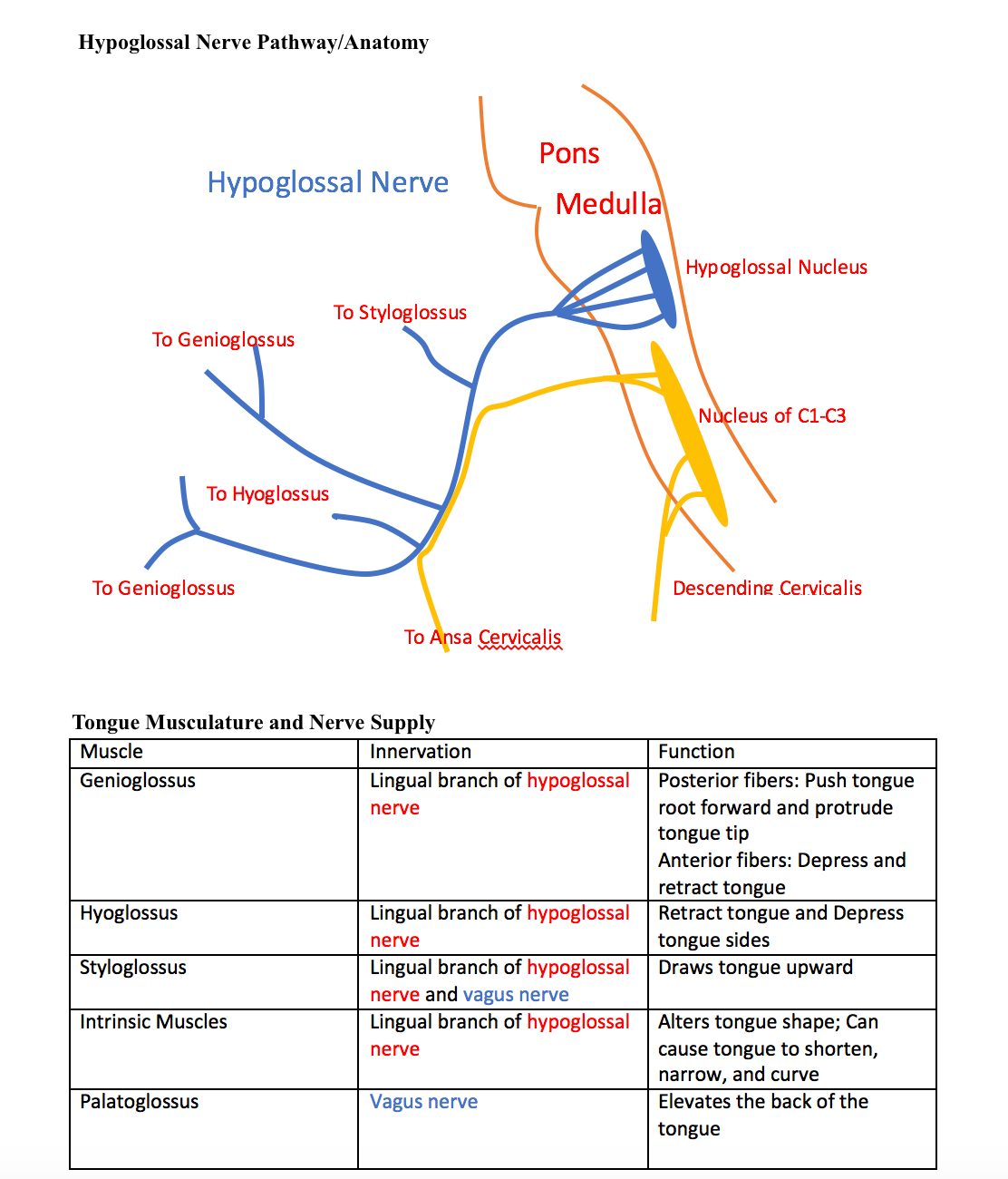

The hypoglossal nerve is mainly a somatic efferent (motor) nerve to innervate the tongue musculature (see Image. Hypoglossal Pathway/Anatomy, Tongue Musculature and Nerve Supply Table.) The nerve also contains some sympathetic postganglionic fibers from the cervical ganglia, which innervates tongue vessels and small glands in the oral mucosa.

The hypoglossal nerve consists of 4 branches: the meningeal, descending, thyrothyroid, and muscular. However, only the muscular branch is part of the real hypoglossal nerve originating from the nucleus. Other branches originate from spinal nerves (mainly C1/C2) or the cervical ganglia. The meningeal branch arises from the C1 and C2 nerves to the posterior cranial fossa. The descending branch carries information from C1 and C2/C3 to innervate the neck muscles (omohyoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid). The thyrothyroid branches innervate the thyrohyoid muscle of the neck. The descending and thyrohyoid branches mostly originate from the cervical plexus.

The muscular/lingual branch is a general somatic efferent (GSE). It innervates all the tongue muscles (intrinsic and extrinsic) except for the palatoglossus, which receives motor innervation from the vagal nerve (CN X). The muscular branch controls most tongue actions, including protruding, retracting, depressing the tongue, and changing the tongue’s shape (see Image. Arteries and Veins of the Tongue).[1][2]

Embryology

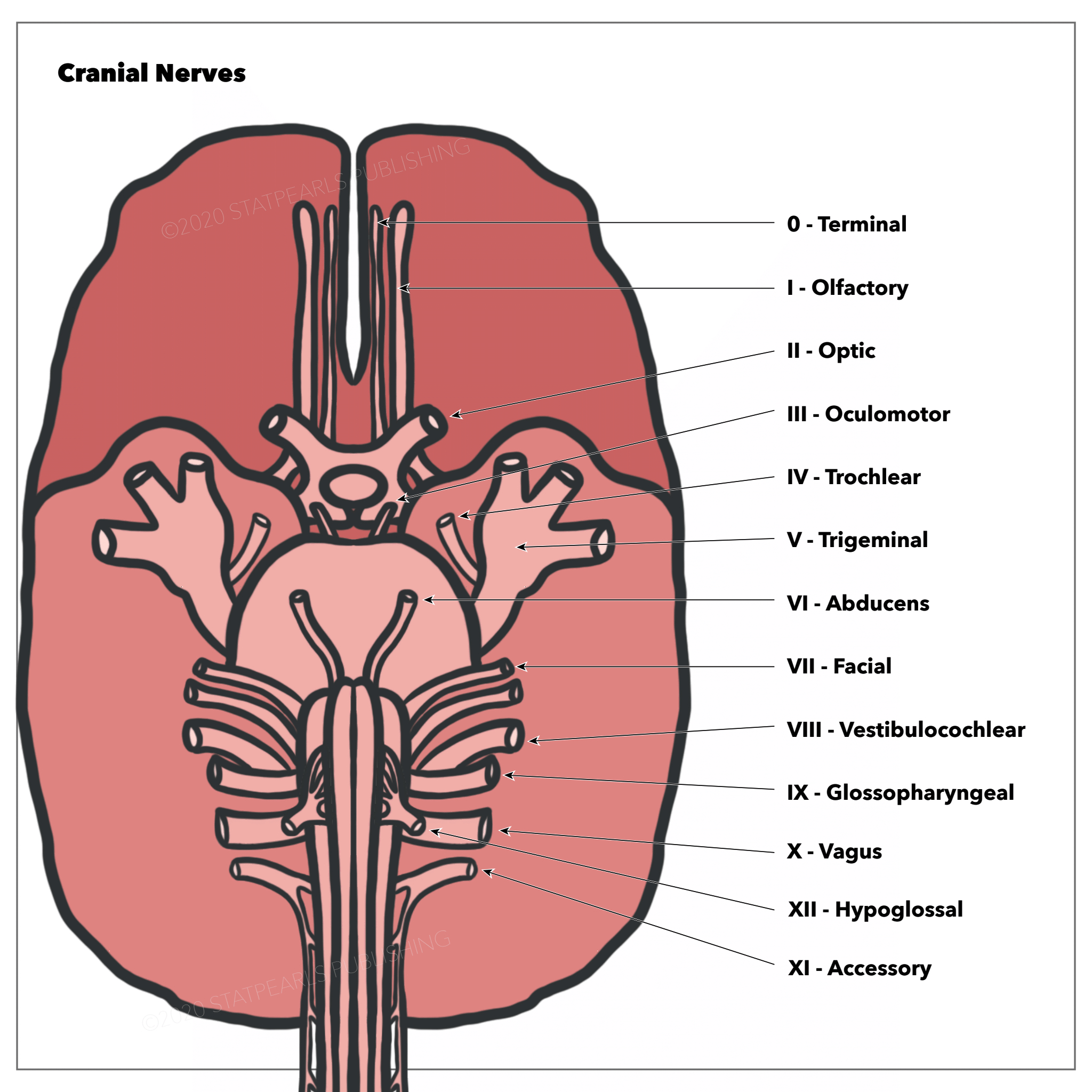

Hypoglossal nerves are part of a group of cranial nerves homologous to ventral roots of spinal nerves and originate from the somatic efferent column of the brainstem (see Image. The Cranial Nerves). The 12th cranial nerve forms from the fusion of ventral root fibers of 3 to 4 occipital nerves. These nerve fibers grow from the hypoglossal nucleus and branch into small hypoglossal nerve roots, leaving the ventrolateral side of the medulla, which converges again to form the cranial nerve XII common trunk. They grow rostrally until contact with the tongue muscles. As the neck develops, the hypoglossal nerve gradually extends upward.[2][3]

Nerves

The hypoglossal nerve’s course starts from the hypoglossal nuclei pair in the lower medulla. The 2 nerves travel laterally and ventrally from the respective nucleus. The nerve splits in 2 before exiting the medulla and passes through the hypoglossal canal in the skull's occipital bone. The nerve reforms and descends through the neck to the angle of the mandible and travels underneath the tongue to innervate the tongue muscles.

At the early portion of the course, the nerve is below the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and near the vagus nerve. Then, the nerve travels above the hyoid bone and between the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles before branching to the various parts of the tongue musculature.[1]

Muscles

The hypoglossal nerve innervates all the intrinsic muscles and all but 1 of the tongue's extrinsic muscles (genioglossus, styloglossus, and hyoglossus). The function of each muscle/muscle group is as follows:

- Genioglossus: Draws the tongue forward from the root

- Hyoglossus: Retracts the tongue and depresses its side

- Styloglossus: Draws the tongue upward

- Intrinsic muscles (superior/inferior longitudinales, transversus, verticalis): Changes the shape of the tongue, such as shortening, narrowing, and curving the tongue.[1]

Surgical Considerations

The hypoglossal nerve is at high risk of injury during carotid endarterectomy.[4]

Clinical Significance

Clinical Examination[5]

Examining the hypoglossal nerve involves observing the primary innervation target of the nerve, the tongue. The 3 observable aspects of the tongue are strength, bulk, and dexterity. Special attention is given when the tongue is weak, atrophied, moving abnormally, or impaired.

The tongue is first observed for position and appearance while resting. Then, the patient is asked to protrude the tongue, move it in and out, side to side, and up and down. The patient does each movement twice: once slowly and the next rapidly. Dexterity is tested by having the patient repeat sounds involving the tongue, such as saying "la la la" or using words with "t" or "d" sounds. Testing strength consists of the patient forcing the tongue to the side against the patient’s cheek while the examiner tries to dislodge the tongue using his/her finger. The tongue’s strength can be checked more accurately using the tongue blade. The strength test is especially useful in testing for unilateral weakness caused by ipsilateral hypoglossal nerve damage.

Hypoglossal Nerve Lesions

The hypoglossal nerve can be damaged at the hypoglossal nucleus (nuclear), above the hypoglossal nucleus (supranuclear), or interrupted at the motor axons (infranuclear). Such damage causes paralysis, fasciculations (as noted by a scalloped appearance of the tongue), and eventual atrophy of the tongue muscles. When 1 of the 2 nerves is damaged, the tongue, when protruded, deviates towards the damaged nerve because of the overaction of the strong genioglossus muscles.

Supranuclear lesions occur at the cerebral cortex, the corticobulbar tract of the internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, or the pons. Supranuclear lesions cause the tongue to protrude away from the nerve because of predominant neural crossing for upper motor neurons. Supranuclear lesions do not tend to cause atrophy but can lead to an uncoordinated tongue with slow but spastic tongue movements. Supranuclear lesions commonly result from strokes but can also be caused by pseudobulbar palsy.

Infranuclear and nuclear lesions cause weakness of the tongue but additionally cause ipsilateral atrophy. Lower motor neuron disease can also cause fasciculation when localized to the lower motor neurons.

Unilateral lesions are not typically a serious problem for patients, as the remaining hypoglossal nerve partly compensates any impediments. However, bilateral lesions can cause profound difficulty with speech and swallowing, as the patient cannot protrude the tongue for these necessary functions.

Hypoglossal nerves can be damaged unilaterally by a multitude of causes, especially tumors, infection, or trauma. The concept of trauma includes surgical trauma, as with carotid endarterectomy (surgery to remove the plaques from the carotid artery). Rare bilateral lesions can be the result of radiation therapy.

Hypoglossal Nerve in Neurologic Disorders

Progressive bulbar palsy and advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) can cause severe tongue atrophy and an inability for the tongue to protrude, leading to the inertia of the tongue (glossoplegia). Fasciculations frequently occur with atrophy in the case of motor neuron disease. Tremors can also occur on the tongue in the case of alcoholism, parkinsonism, and paresis.[6]

Neck-Tongue Syndrome

Neck-tongue syndrome is a pain on 1 side of the upper neck or back of the head, usually involving rapid neck rotation. The syndrome also typically involves the tongue, causing the ipsilateral side of the tongue to feel the pain. The syndrome's cause is unknown, although 2 theories have been suggested, and both involve strain/pressure on the C2 nerve. As the C2 nerve route is involved with the hypoglossal nerve route, tongue pain can result.[7][8][7]

Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulation

In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the decrease in muscle tone of the genioglossus muscle causes the tongue to retract and impede airflow into the trachea. The hypoglossal nerve stimulator is 1 possible treatment if the patient is refractory to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral devices, or surgery. Mild hypoglossal nerve stimulation causes the nerve to pull the tongue forward, enabling better airflow.[9][10]