Definition/Introduction

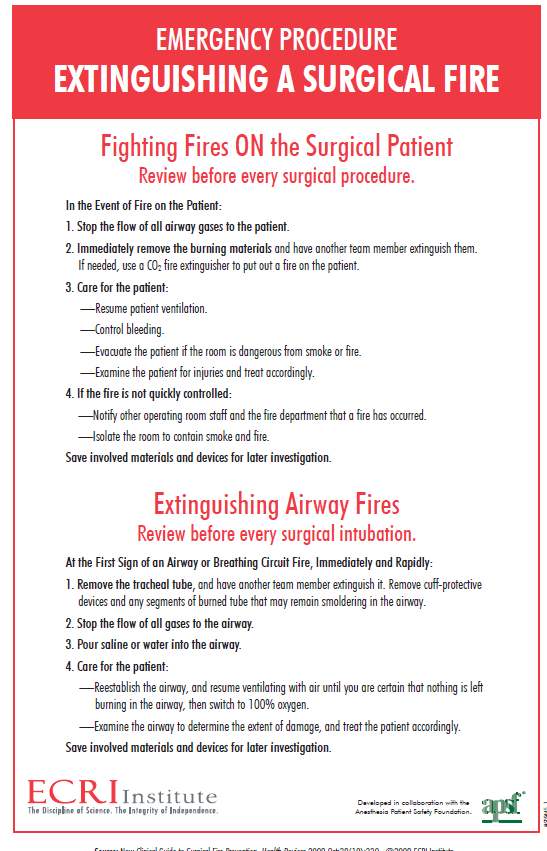

The definition of a surgical fire occurs in, on, or around a patient undergoing a surgical procedure. Urologists, as with all surgeons, utilize and bring the components of the fire triangle into proximity, increasing the risk of a surgical fire. Three main components of the fire triangle are required for a surgical fire: a fuel source, an oxidizer, and an ignition source.[1] The first component is a fuel source. Familiar fuel sources include degreasers, prepping agents, drapes, towels, sponges, dressings, tapes, gowns, hoods, masks, ointments, benzoin, aerosols, alcohol, mattresses, pillows, blankets, ECG electrodes, hoses, tissue, GI gases.[2] The second component is an oxidizer. Common oxidizers are room air, oxygen, and nitrous oxide.[2] Lastly, the third necessary component is an ignition source. Familiar ignition sources include a light source, laser, electrocautery, sparks from high-speed drills and burrs, defibrillators, glowing embers of charred tissue, flexible endoscopes, and tourniquet cuffs.[2] Sources of these 3 components are often present close to the patient in the medical setting or operative suite. A further risk factor for surgical fires is a high oxidizer level or elevated oxygen concentration greater than the normal atmospheric oxygen level of 21%. This risk is particularly high during head and neck, oral pharyngeal, and rectal surgeries, where higher oxygen levels or methane gas may be present.[3] Oxidizer levels cause a decrease in the ignition point temperature of fuels. Curiously enough, inhaled halogenated anesthetics are similar to halogenated fire extinguishing agents, which are considered non-flammable and may be protective of endotracheal tube fires.[4] Nonetheless, the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI) has ranked surgical fires as 1 of their top 10 technological hospital hazards for patients.[2] See Table. Emergency Procedure for Extinguishing a Surgical Fire.

Very few surgical fires are unpreventable, and all surgical fires should be considered a never event. Surgical fires likely range from 550 to 650 annually, which is about as common as incorrect surgical site procedures. With so many fires occurring, this also raises concerns regarding the frequency of “near miss” surgical fires or the number of unreported fires or burns.[5]

Issues of Concern

Because surgical fires are preventable, surgeons are necessary to prevent them. The Food and Drug Administration, in conjunction with the Joint Commission, has made many recommendations to prevent surgical fires. Prevention can be divided into 2 categories: preoperative and intraoperative strategies.

Education and knowledge are essential elements of preoperative prevention. The prevention begins with monitoring surgical equipment for damage or electrical concerns and utilizing manufacturer specifications on device usage and maintenance for OR machines. Individuals’ awareness and assessment of devices and the specific risks with devices such as lasers, fiber optic light cords, and electrocautery are other necessary components for prevention. Knowledge regarding fire risks, including the fire triangle and proper protocols for response to surgical fires, can help staff eliminate the risks and address situational concerns if a fire arises.[6] Good communication between all OR team members, including anesthesia, the surgical team, the nursing team, and other components, reduces the risk to the team and the patient in the OR setting. This communication typically begins with a surgical time-out or briefing before procedure initiation.[2] By communicating before the procedure, team members can point out particular risk factors and discuss the sources of fuels, oxidizers, and specific ignition sources within a procedure.

Intraoperatively, prevention also requires specific actions and knowledge from all individuals within the OR suite. For example, within the fire triangle, oxidizers used by anesthesia decrease ignition point temperature, which increases the risk of preventable fires. The fire triangle provides a simple system within the OR settings that can illuminate potentially unnoticed or unrecognized risks. This knowledge can be applied, for example, to use the lowest amount of oxygen to maintain the required oxygen saturation.[7] Additional mechanisms that can be utilized to prevent fires include using appropriate skin preparation techniques, following manufacturer specifications for dry time on alcohol-based skin prep, and preventing preparation fluid pooling.[8] Additionally, properly using surgical devices, such as re-holstering the cautery and minimizing cautery currents, can reduce risk.[9] Lastly, staff should be aware of the number of instruments that generate heat, such as lasers and light cords used in endoscopic and laparoscopic cases by urologists, which can also reduce the fire risk. By applying this knowledge to all elements of the OR suite, the reduction in cross-contact between fuel sources, ignition sources, and oxidizers can significantly decrease the potential risks to the patient throughout a surgical procedure.

Clinical Significance

The importance of surgical fire prevention cannot be diminished and is an essential concern for surgeons. Surgical fires cause harm to the patient, increase adverse outcomes, increase the cost of health care, and are associated with significant litigation. Of 114 cases identified involving surgical fires, 60% of these resulted in a median award of $215000 to the plaintiff.[10] Given that OR fires can occur on or in the patient, the risk of substantial harm to the patient, rather than just to the surgical suite, heightens the need for prevention. Of particular concern is that a fire on or in a patient can cause burns that may lead to irreversible tissue damage. This tissue damage occurs by denaturation and coagulation of proteins. With this damage, the inflammatory cascade is activated, which can cause vasoconstriction, vasodilation, increased capillary permeability, and edema locally and at distant tissues.[11]

In addition to direct harm to the patient, fires within the operative suite likely cause indirect harm through smoke inhalation. Very few cases of urologic surgical fires appear in the literature. However, 1 case report involved a hypospadias repair where prep fluid ignited under the drapes, causing first and second-degree burns to the patient’s perineum.[12] A case series from Egypt involving more than 82,000 urological surgeries found 18 cases associated with surgical fires: 6 electrosurgical theater fires, 7 contact burns, 3 electrosurgical internal injuries, and 2 electrocutions.[13] The number of surgical fires and burns in this series is quite high compared to an incidence of 0.32 to 0.63 per 10,000 operations found by Clarke JR, Bruley ME.[13] Upon review of the literature within the United States, no reported surgical theater fires or electrocutions are associated with urology, which may be attributed to variations in the maintenance and monitoring of operating room devices. This data contradicts other data showing that 85% of the fires were reported to be associated with airway or head and neck surgery.[7] Egyptian data may be more accurate than data from the United States because of the variations in reporting in the country.

Fortunately, most fires occur at operative sites distant from the typical urologic operative sites. In addition, urologists utilize tools and techniques that reduce the risk and contain risk factors. For example, urologists often operate using irrigation and iodine prep, which reduce the risk of operative fires. Urologists also often use many devices, such as light cords or flexible endoscopes, that can cause sparking. Within certain types of procedures, such as abdominal surgeries, urologists may conduct a bowel resection, which increases the risk of bowel gas ignition as well as electrocution. Another example may be the rare cases where a urologist operates above the xiphoid process for a buccal graft, which exposes urologists to even higher risk due to proximity to oxygen delivery devices.

While surgical fires are avoidable, and the hope is that they never occur, having a calculated and articulate response is still necessary for reducing harm. The risk to a patient could result in devastating consequences, and a swift and practiced response could reduce those risks to the patient and the OR staff. The response varies with the location of the fire and the cause and requires specific training for each. An excellent step-by-step guide was created by ERCI that is useful when training OR staff (image 1). The step-by-step guide for fires on or in the patient requires the following action steps: Stop administering supplemental gas, remove the material on fire, and extinguish the active fire. Next, assess the patient and provide the necessary care. Lastly, the appropriate individuals should be notified, and the room should be isolated if the fire cannot be controlled or contained.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

An interprofessional team approach is required to prevent the outbreak of a surgical fire. Good communication between all the OR members is a must. Surgical time-out is the most critical time point for detailing all the sources of fuels, oxidizers, and specific ignition sources within a procedure.

- Surgeons must have detailed knowledge about the mechanics of all the energy devices used in the OR. Awareness and assessment of these devices and their specific risks are necessary components for the prevention of surgical fire.

- Anesthesiologists play a critical role in surgical fire safety. They must ensure that the patient is not provided with unnecessary increased oxygen levels, as this reduces the ignition point temperature. They must also have a thorough knowledge of anesthetics that reduce the risk of surgical fire (eg, halogenated anesthetics).

- The nurse shall ensure the appropriate skin preparation techniques, including following manufacturer specifications for dry time on alcohol-based skin prep and preventing preparation fluid pooling.

- OR technicians shall remain cautious about the proper use of surgical devices, such as re-holstering the cautery, lasers, and light cords used in endoscopic and laparoscopic cases.