Introduction

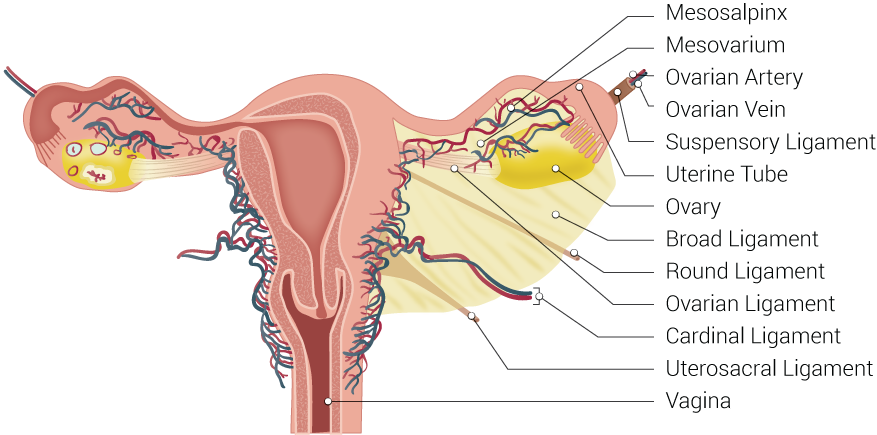

The broad ligament of the uterus is a double-layer fold of the peritoneum that attaches the lateral portions of the uterus to the lateral pelvic sidewalls. [1][2][3] The broad ligament is divided into the mesometrium (the largest portion), the mesosalpinx (mesentery of the uterine [fallopian] tubes), and the mesovarium (connects the ovaries to the broad ligament). The broad ligament contains the following structures:

- Fallopian tubes

- Ovaries

- Ovarian arteries

- Uterine arteries

- Round ligaments

- Suspensory (infundibulopelvic) ligaments

- Ovarian ligaments

The broad ligament of the uterus serves as mesentery to the female pelvic organs and contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics.

Structure and Function

The broad ligament functions as a protective layer for the female pelvic organs. It carries blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics to the structures within the mesentery. The broad ligament consists of a double layer of peritoneum, and the different parts are named based on the structures contained between the double layer. The mesometrium is the largest portion and extends laterally from the entire surface of the uterus. The mesosalpinx is the fold of peritoneum draping over both uterine tubes, and the mesovarium is the fold attaching the anterior portion of each ovary to the posterior part of the broad ligament. The mesovarium does not cover the entire surface of each ovary but helps to keep its position within the pelvis.[4][5]

Although the broad ligament helps to support the uterus and maintain its position in the pelvic cavity, it does not serve as the primary support for the uterus. Three pairs of ligaments help to maintain the position of the uterus within the pelvis. These include the cardinal ligaments, the pubocervical ligaments, and the uterosacral ligaments. These 3 sets of ligaments run along the base of the broad ligament and serve as primary supports. The cardinal ligaments, also known as the transverse cervical ligaments, the lateral cervical ligaments, or Mackenrodt’s ligaments, are fibrous bands that attached the cervix to the lateral pelvic walls. The pubocervical ligaments are a pair of fibrous bands that attach the anterior portion of the cervix to the posterior pubic symphysis. The uterosacral ligaments are another pair of fibrous bands that attach the posterior cervix to the anterior surface of the sacrum. [6]

The broad ligament and the round ligaments of the uterus serve as secondary support for the uterus within the pelvis.

Embryology

The broad ligament forms after the Mullerian ducts join together during development. The fusion of these ducts leads to the development of the female pelvic organs. During this process, 2 layers of peritoneum join together enveloping the pelvic organs, which is then known as the broad ligament.

The round ligaments are remnants of the gubernaculum, which forms during development. In males, the gubernaculum guides the testes through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. In females, the remnants are called the round ligaments of the uterus. They connect to the anterior horns of the uterus and travel anteriorly in the pelvis to the deep inguinal rings where they move through the inguinal canal and attach to the labia majora. The round ligaments help to keep the uterus in an anteverted position, flexed forward over the bladder. The uterus is anteverted in the majority of women. However, the angle and position of the uterus are highly variable. During pregnancy as the uterus expands and moves out of the pelvis, the round ligaments can be stretched which causes discomfort in some women.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The broad ligament contains the blood vessels to the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus. The ovarian arteries branch from the abdominal aorta and run through the suspensory ligaments of the ovaries, also known as the infundibulopelvic ligaments. The suspensory ligaments attach each ovary to the pelvic sidewall. The ovarian ligaments, which connect each ovary to the lateral side of the uterus, do not contain any blood vessels. These are also known as the utero-ovarian ligaments or the proper ovarian ligaments.

The uterine arteries branch from the internal iliac arteries and travel to the uterus via the cardinal ligaments, or lateral (transverse) cervical ligaments, which run along the base of the broad ligament. The ovarian arteries run superiorly to the ureters within the pelvis, which can be remembered by the mnemonic “water under the bridge."

The fallopian tubes receive arterial blood supply from both the ovarian and uterine arteries.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Defects in the broad ligament can lead to herniation of the bowel, uterine tubes, or ovaries. Most defects of the broad ligament are unilateral and may be partial or complete. When the defect is partial, there is a risk of internal bowel herniation, usually the ileum and rarely the colon. A plain abdominal x-ray may show dilated bowel loops with air-fluid levels if this occurs. The diagnosis is made with a CT scan and requires surgical correction. Other rare types of herniation include tubal and ovarian torsions. Defects in the broad ligament can be congenital or acquired from prior pelvic surgery, pregnancy, endometriosis, or pelvic inflammatory disease.[9]

When performing a hysterectomy, the surgeon has to ligate the blood supply to the uterus upon removal of the uterus and fallopian tubes. The surgeon must be sure to spare the ureters during this process, as they run very near the uterine arteries. It is important to remember that the ureters run inferiorly (under) the uterine arteries, as stated in the mnemonic “water under the bridge." After the hysterectomy is complete, the surgeon will perform a cystoscopy to make sure no damage was done to the ureters during the operation. If the surgeon is also removing the ovaries, then the ovarian vessels must be ligated as well as run through the infundibulopelvic ligaments.

Clinical Significance

The broad ligament draping across the pelvic organs contributes to the vesicouterine pouch between the bladder and uterus as well as the rectouterine pouch between the uterus and rectum. The rectouterine pouch, also known as the pouch of Douglas or posterior pelvic cul-de-sac, can accumulate fluid after a ruptured ectopic pregnancy or an ovarian cyst. This is because the rectouterine pouch is the lowest point in the peritoneal cavity when an individual is sitting or standing. Secondarily, the ovaries are located posteriorly to the broad ligament, so any fluid arising from ovarian pathology will gather in the rectouterine pouch. A culdocentesis can be performed, which involves aspirating peritoneal fluid from the rectouterine pouch for diagnostic purposes. This is performed by inserting a needle through the vagina and accessing the space posterior to the cervix through the posterior vaginal fornix.[10][5]

The broad ligament is a site where endometriosis is commonly found. This occurs when small portions of the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, grow outside of the uterus and are still affected by hormone cycles. These pieces of tissue can form cysts, called endometriomas, which are filled with blood from endometrial glands. They can occur anywhere in the pelvis and can cause pelvic pain, bleeding, and adhesions. During laparoscopy, these cysts appear dark brown, blue, or black and are sometimes called "chocolate cysts" or "powder-burn lesions."

In very rare cases, malignant leiomyosarcomas can arise from the broad ligament. In these cases, the tumor must be removed completely which may require a total hysterectomy. Lipoleiomyomas may also arise from the broad ligament, which are benign tumors that are a variant of uterine leiomyomas. These present with a lower abdominal mass which may or may not be painful. The tumors may also need to be surgically removed if symptomatic.