Introduction

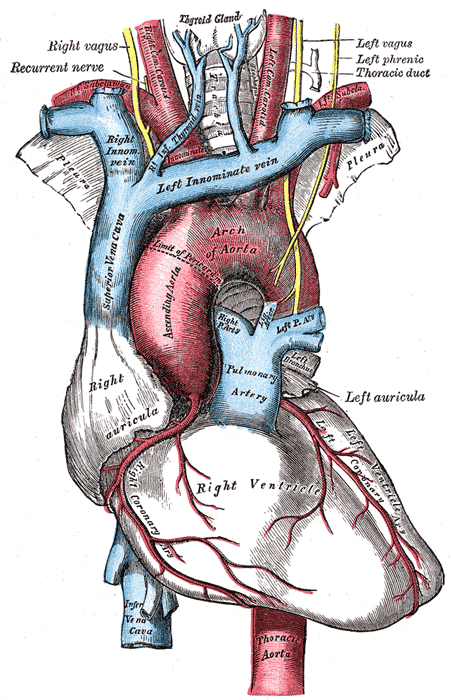

The aortic arch is the section of the aorta between the ascending and descending aorta. As it arises from the ascending aorta, the arch runs slightly backward and to the left of the trachea. The distal segment of the aortic arch then traverses downwards at the fourth thoracic vertebra. From this point on, it continues as the descending aorta.

The aortic arch has 3 major branches. The brachiocephalic trunk is the first branch of the aortic arch and supplies blood to the right arm, right head, and neck. The left common carotid artery is the second branch of the aortic arch, which supplies blood to the left side of the head of the neck. The last branch of the aortic arch is the left subclavian artery that distributes blood to the left arm.[1]

Structure and Function

The aortic arch is the segment of the aorta that helps distribute blood to the head and upper extremities via the brachiocephalic trunk, the left common carotid, and the left subclavian artery.

The aortic arch also plays a role in blood pressure homeostasis via baroreceptors found within the walls of the aortic arch. These receptors respond to stretching of the aortic wall and send a signal to the nucleus of the solitary tract in the brainstem via the vagus nerve, which can subsequently inhibit or disinhibit the sympathetic nervous system or activate the parasympathetic nervous system. This is one of the major mechanisms that helps prevent quick, drastic changes in blood pressure.

The aortic arch also has peripheral chemoreceptors known as aortic bodies that monitor blood composition, specifically the partial pressure of carbon dioxide and oxygen. Changes in either gas level will result in a signal being sent to the dorsal respiratory group in the brainstem via the vagus nerve, which will regulate breathing accordingly.

Embryology

The aortic arch derives from the left branch of the fourth pharyngeal arch during the fourth week of embryonic development. The lower part of the fetal aortic arch connects to the ductus arteriosus. This allows blood from the right ventricle to bypass the pulmonary arteries and avoid fetal lungs that are not being utilized. Soon after birth, the ductus arteriosus starts to close off and becomes the ligament arteriosum.

Physiologic Variants

Variations in the aortic arch and its branches are not rare. Rarely, the left common carotid artery may originate from the right-sided brachiocephalic artery rather than the aortic arch. In other individuals, the left common carotid and the brachiocephalic artery may have a common origin. In even rare cases, the brachiocephalic artery may give rise to all 3 branches.[2]On a plain chest x-ray, the aortic knob is often seen as a prominent shadow. It does not represent an aneurysm even when it is calcified. In some cases, the aortic arch forms a mirror image and is known as a double aortic arch. A posterior indentation on a barium swallow in an infant may be suggestive of a double aortic arch. The key reason why double aortic arch is of clinical interest is that it is associated with esophageal atresia or a congenital laryngeal web. Many infants may be asymptomatic, but a few may present with feeding difficulties.The diagnosis of a double aortic arch is made with a barium swallow, and a posterior indentation of the esophagus may be seen. This test is followed by an echo or a CT angiogram to assess the aortic arch and the presence of other congenital problems.[3]In some infants, the origin of the innominate artery may be abnormal and lead to compression of the trachea. Aortopexy is a procedure when the innominate artery or the aortic arch is fixed to the posterior sternum. This helps prevent tracheomalacia.[4]

Surgical Considerations

The main surgical consideration of the aortic arch is avoidance of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve travels posterior to the distal aortic arch, loops around, and travels back up and anterior to the aortic arch. Damage to this nerve during surgery can result in voice hoarseness or vocal cord paralysis.

Clinical Significance

Aortic dissection is a serious complication that can affect the aortic arch. It is defined as the separation of the innermost layer, the tunica intima, from the other 2 layers of the aorta. This separation allows blood to flow into the tunica media layer. Aortic dissection is commonly grouped into Stanford type A and type B depending on its location along the aorta. Stanford type A dissection involves the ascending aorta and the aortic arch. Aortic dissection is classically described as severe, tearing chest pain that radiates to the back. This is diagnosed with computed tomography angiography. While chest X-rays may show mediastinal widening, this diagnostic test has a low sensitivity for aortic dissection. Many serious complications result from an aortic dissection, including rupture of the aorta. Additionally, the tear in the tunica intima may extend into the aortic valve, causing aortic regurgitation. Although uncommon, dissections of the aortic arch may lead to decreased blood flow to the head and/or upper extremities due to an intimal flap blocking one of the three major branches of the aortic arch. [5][6]

Aneurysms are defined as localized dilation of an artery. They can develop nearly anywhere along the aorta and commonly involve the aortic arch. Aneurysms of the aortic arch are often asymptomatic and are found incidentally. They need to be closely monitored and may require surgical intervention to ensure that an aneurysm does not rupture, which is a complication that is often fatal. Aneurysms that are significant enough and are localized to the aortic arch without the involvement of the descending aorta may require a complete aortic arch replacement.

The isthmus is the narrowed portion of the aortic arch located just before the descending aorta begins. When the narrowing of the isthmus is significant, this can result in aortic coarctation. Individuals with coarctation of the aorta may be asymptomatic until later in life. Symptoms may include syncope, shortness of breath, epistaxis, headache, and chest pain. It is twice as common in males and commonly associated with Turner syndrome.