Continuing Education Activity

An adductor strain or injury to the adductor muscle group of the thigh is a common cause of medial leg and groin pain, especially among athletes. This activity reviews the presentation, evaluation, and management of adductor strains and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify common mechanisms of injury for adductor strains.

Describe the presentation of a patient with an adductor strain.

Explain how to treat an adductor strain.

Identify interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and improve outcomes for patients with adductor strains.

Introduction

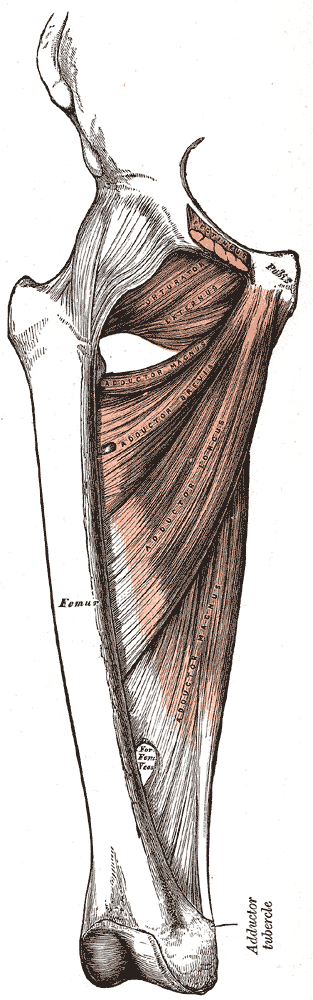

Adductor strain or injury to the adductor muscle group is a common cause of medial leg and groin pain, especially among athletes. The adductor complex includes the three adductor muscles (longus, magnus, and brevis) of which the adductor longus is most commonly injured. All three muscles primarily provide adduction of the thigh. Adductor longus provides some medial rotation. The adductor magnus also has an attachment on the ischial tuberosity, giving it the ability to extend the hip. In open chain activation, the primary function is hip adduction. In closed chain activation, they help stabilize the pelvis and lower extremity during the stance phase of gait. They also have secondary roles including hip flexion and rotation.[1][2]

Adductor Magnus

- Origin: Inferior pubic ramus, ischial tuberosity

- Insertion: Linea aspera, adductor tubercle

Adductor Brevis

- Origin: Inferior pubic ramus

- Insertion: Linea aspera, pectineal line

Adductor Longus

- Origin: Anterior pubic ramus

- Insertion: Linea aspera

The primary adductor complex is accompanied by three additional muscles with adduction activity including the gracilis, which also participates in internal rotation and hip flexion; obturator externus, which can also externally rotate; and pectineus, which additionally assists in hip flexion.

Gracilis

- Origin: Inferior pubic symphysis, pubic arch

- Insertion: Proximal medial tibia, pes anserine

Pectineus

- Origin: Pectineal line of the pubis

- Insertion: Pectineal line of femur

Obturator Externus

- Origin: Obturator foramen

- Insertion: Posterior aspect of the greater trochanter

The obturator nerve (L2 to L4), arising from the lumbar plexus, innervates all three. The adductor magnus also is innervated by the tibial nerve (L4 through S3).

Etiology

Adductor strain is a common injury among soccer and hockey players. Other common sports related to adductor strain include football, basketball, tennis, figure skating, baseball, horseback riding, karate, and softball. Risk factors include previous hip or groin injury, which is likely the greatest risk, as well as age, weak adductors, muscle fatigue, decreased range of motion, and inadequate stretching of the adductor muscle complex. Biomechanical abnormalities including excessive pronation or leg-length discrepancy can also contribute.[3][4]

Suddenly changing direction causes rapid adduction of the hip against an abduction force, putting exaggerated stress on the tendon. Sudden acceleration in sprinting is the most common mechanism of injury. Jumping and overstretching the adductor tendon are less common causes.

Epidemiology

Muscle strain is the primary injury among athletes, accounting for up to 31% of visits. Among European soccer players, adductor muscle injuries were the second most commonly injured muscle group (23%) behind hamstrings (37%).

In another study of soccer players, adductor pain/strain represents anywhere from 9% to 18% of all injuries. In sub-elite, male soccer players, adductor strain accounted for 51% of all groin pain.

Pathophysiology

Most muscle tendon strains occur while the muscle is being forcibly stretched while being concentrically contracted. The greatest eccentric tension is placed on the adductor complex when the leg is in external rotation and abduction. Adductor injuries typically occur when the athlete pushes off in the opposite direction. As a result, the adductor muscles contract to generate both eccentric and concentric opposing forces. The dominant leg is more commonly injured and more likely to sustain significant injury.

For example, a soccer player trying to kick a ball with an externally rotated leg using the inside of their foot. If their leg swinging in adduction meets a significant resistive abductive force such as another player, this can place a significant load on the adductor complex leading to injury.

The musculotendinous junction is the most common site of injury in a muscle strain. The adductor tendons have a small insertion zone which is characterized by an area of poor blood supply and rich nerve supply which helps explain the increased degree of perceived pain.

The adductor longus is the most commonly injured muscle and accounts for 62% to 90% of cases. It is hypothesized that this occurs due to its low tendon to muscle ratio at the origin. Rugby players with an adductor-abductor strength ratio of less than 80% are 17 times more likely to sustain an adductor injury.[5]

History and Physical

Patients will often describe a sudden onset of pain during a specific activity as opposed to a more insidious onset. They will describe the pain as severe and in the groin region or medial thigh that is worse with activity.

Individuals can sustain injury anywhere along the medial compartment of the thigh along the adductor complex. The clinician may observe bruising or swelling in moderate to severe injuries. Typically, there is an area of point tenderness or localized tenderness. They may be tender along the proximal attachment of the pubic ramus. The patient will have pain with resisted adduction of the hip or with passive stretching. They may have decreased strength secondary to pain or depending on the degree of injury, this strength deficit may be due to muscle or tendon rupture or avulsion injury.

Evaluation

Radiographic evaluation is the initial modality of choice for suspected adductor strain. Anteroposterior views of the pelvis and frog-leg view of the affected hip are recommended as initial imaging studies. In most patients, these images will be normal in appearance; however, occasionally one may observe an avulsion injury. These images can also help evaluate for other causes of groin pain such as osteitis pubis, apophyseal avulsion fractures, and pelvic or hip stress fractures.

If further imaging is needed, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended. This is likely to show muscle edema and hemorrhage at the site of injury. If there is a bony injury, this will be better elucidated on the MRI.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound can further visualize the tendon and bony attachment sites, muscles, ligaments, and nerves. Ultrasound can be used to identify the area and extent of the injury and used to evaluate periodically during the recovery phase.

Treatment / Management

Most adductor strains are managed conservatively. Initial management will include relative rest from sports, ice, compression, analgesia, and physical therapy. Analgesia typically includes acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. The rehabilitation program should include stretching the range of motion and strengthening of the affected leg and core accompanied by a gradual return to sport. Acute injuries may return as quickly as 4 to 8 weeks while chronic strains may take many months to achieve desired results.[6][7][8]

In addition, other treatment modalities may be available for refractory cases. This includes corticosteroid injection into the adductor complex and needle tenotomy, both of which are at the discretion of the consulting clinician and typically performed under ultrasound guidance.

Occasionally, surgical management is indicated. There are no clear guidelines on which injuries require surgical management. Potential indications include poor recovery with conservative management with full-thickness tears or avulsion injuries with the persistent weakness of the affected limb.

Differential Diagnosis

The musculoskeletal differential diagnosis of groin pain is broad and includes tendonitis (iliopsoas, rectus femoris), bursitis (iliopsoas), athletic pubalgia (sports hernia, sportsman’s hernia, pre-hernia complex, Gilmore groin), hip joint pathology (osteoarthritis, femora-acetabular impingement, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, avascular necrosis), osteitis pubis, sacroiliac dysfunction, neuropathic pain (radiculopathy, sciatica), and mechanical low back pain.

Nonmusculoskeletal causes of groin pain include urologic disorders, malignancy, gastrointestinal disorders, sexually transmitted infections, and, in women, gynecologic disorders.

Staging

Adductor strain has a 3-tier classification system.

- First degree: Pain without significant loss of strength or range of motion

- Second degree: Pain with loss of strength

- Third degree: Complete disruption of muscle or tendon fibers with loss of strength

Prognosis

The prognosis for adductor strains is generally favorable. Most athletes will return to play with minimal pain and normal function if provided appropriate relative rest and rehabilitation. If they return to play too soon or are inadequately rehabilitated, their pain may lead to chronic injury.

Renstrom et al. found that 42% of athletes with muscle-tendon groin injuries were not able to return to physical activity more than 20 weeks after the initial injury. However, an active training program directed at strengthening and conditioning of muscles of the pelvis and especially the adductor muscles is very effective at treating patients with long-standing, adductor-related groin pain.[9][10]

Complications

Complications of adductor strains primarily include acute pain and missed playing time. In some cases, the pain may be more chronic with associated weakness and inability to return to sport.

Because sport-related groin injuries are a significant contributor to missed playing time, prevention is essential in maintaining a healthy athlete. Prevention programs are directed at adductor strengthening. Maintaining adductor strength at a minimum of 80% of abductor strength has been shown to reduce adductor injuries. One program among NHL players identified as having weak abductors participated in a 6-week preseason strengthening program which reduced adductor strains from 3.2 injuries per 1000 player-game exposures to 0.71.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on treatment for an acute groin strain. This includes adequate protection, rest, ice, compression, and elevation known as PRICE therapy. Patients should be advised to avoid physical activity and sport that may be harmful and delay recovery.

Physical therapy should be directed at strength, the range of motion, and stretching of the affected muscle group. Return to play and activity should be guided by symptom recovery as well as clinician and therapist guidance. Returning players to activity too soon can result in recurrent or chronic injuries and be detrimental to their future careers.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Adductor strain is a common cause of groin injury and pain among athletes.

- Risk factors include previous hip or groin injury, age, weak adductors, muscle fatigue, decreased range of motion, and inadequate stretching of the adductor muscle complex.

- Most injuries can be managed conservatively by their primary care provider with rest, ice, physical therapy, and a graded return to play.

- Refractory patients can be referred to an orthopedic or sports medicine clinician for further treatment and evaluation after non-musculoskeletal causes have been evaluated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Most adductor strains can be managed without consulting an orthopedic or sports medicine clinician. Patients will generally respond well to conservative treatments, physical therapy, and a graded return to athletics. In cases that do not recover quickly, referral to a specialist may be indicated to explore other treatment modalities.

Care is best supported by an interprofessional team of clinicians, nurses, and physical or occupational therapists with pharmacists assisting with pain management.