[2]

Jain V, Ellingson AN, Smoker WR. Lateral pterygoid muscle rhabdomyolysis. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2007 Nov-Dec:28(10):1876-7

[PubMed PMID: 17898189]

[5]

Natsis K, Piagkou M, Repousi E, Tegos T, Gkioka A, Loukas M. The size of the foramen ovale regarding to the presence and absence of the emissary sphenoidal foramen: is there any relationship between them? Folia morphologica. 2018:77(1):90-98. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0068. Epub 2017 Jul 13

[PubMed PMID: 28703850]

[6]

Mitsuhashi Y, Hayasaki K, Kawakami T, Nagata T, Kaneshiro Y, Umaba R, Ohata K. Dural Venous System in the Cavernous Sinus: A Literature Review and Embryological, Functional, and Endovascular Clinical Considerations. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2016 Jun 15:56(6):326-39. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2015-0346. Epub 2016 Apr 11

[PubMed PMID: 27063146]

[7]

Thangavelu K, Kumar NS, Kannan R, Kumar JA. Simple and safe posterior superior alveolar nerve block. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2012 Jan-Jun:6(1):74-7. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.103379. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25885507]

[9]

Fabre C, Atallah I, Wroblewski I, Righini CA. Maxillary sinusitis complicated by stroke. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Dec:135(6):449-451. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.07.004. Epub 2018 Jul 30

[PubMed PMID: 30072286]

[10]

Biočić J, Brajdić D, Perić B, Đanić P, Salarić I, Macan D. A Large Cheek Hematoma as a Complication of Local Anesthesia: Case Report. Acta stomatologica Croatica. 2018 Jun:52(2):156-159. doi: 10.15644/asc52/2/9. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30587858]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[11]

Yue BYT, Zinn R, Roberts R, Wilson J. Use of thrombin-based haemostatic matrix in head and neck reconstructions: a potential risk factor for pulmonary embolism. ANZ journal of surgery. 2017 Dec:87(12):E276-E280. doi: 10.1111/ans.13618. Epub 2016 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 27490907]

[12]

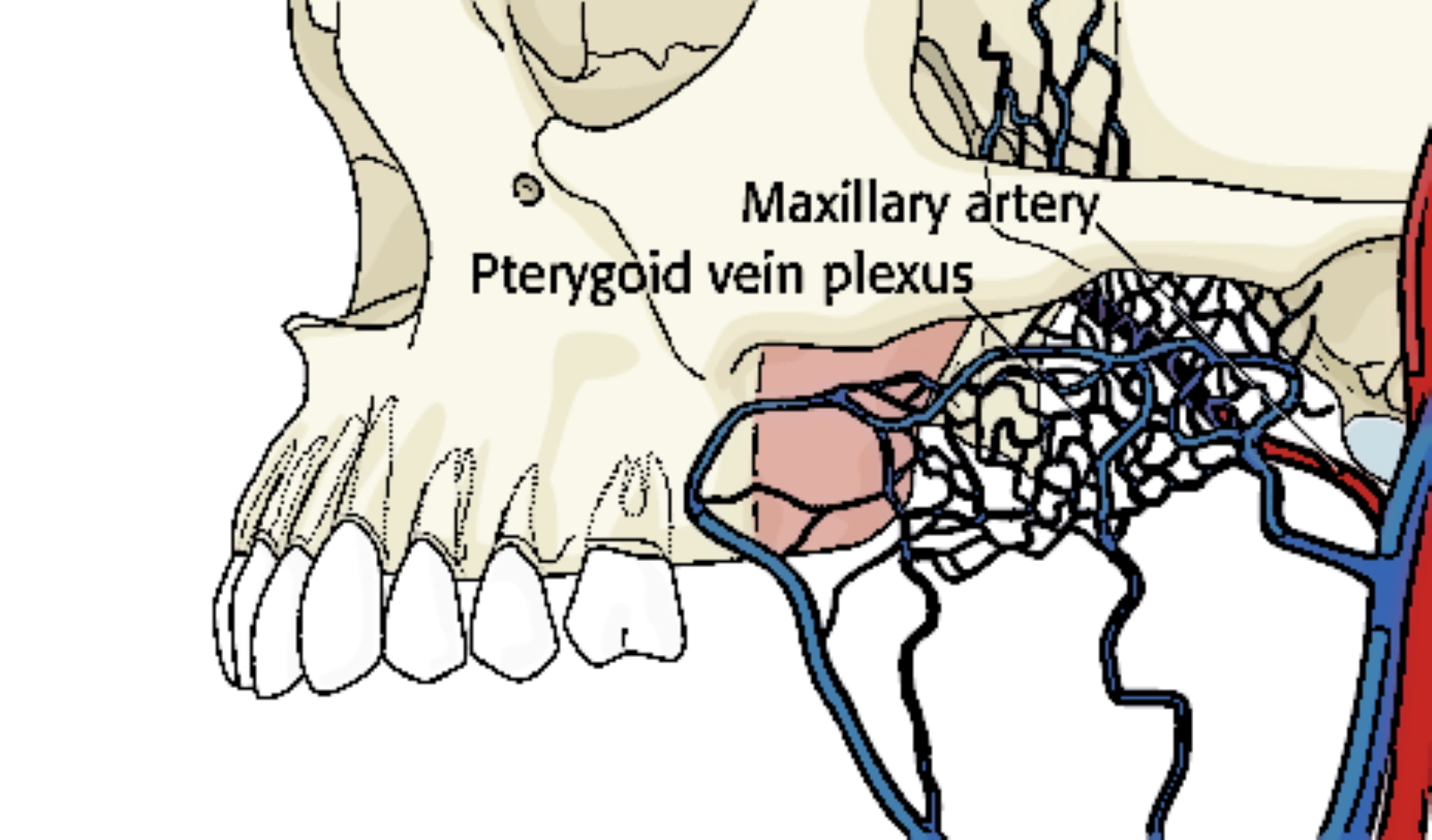

Oshima T, Ogura M, Kikuchi T, Hori Y, Mugikura S, Higano S, Takahashi S, Kawase T, Kobayashi T. Involvement of pterygoid venous plexus in patulous eustachian tube symptoms. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2007 Jul:127(7):693-9

[PubMed PMID: 17573564]