Continuing Education Activity

Acute diverticulitis is inflammation of a diverticulum, a sac-like protrusion from the colon wall, due to micro-perforation. Diverticulitis presents in 10% to 25% of patients with diverticulosis. In the past, diverticulitis was treated surgically, however it is now a medically-managed entity, even in its most acute phase. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of diverticulitis and highlights the importance of a well-coordinated interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition

Objectives:

Identify risk factors for diverticulitis.

Explain the clinical evaluation of a patient with diverticulitis.

Explain how to manage a patient with diverticulitis.

Outline the role of a collaborative interprofessional team in caring for patients with diverticulitis.

Introduction

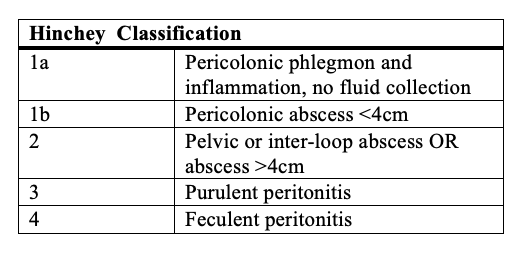

Acute diverticulitis is inflammation due to micro-perforation of a diverticulum. The diverticulum is a sac-like protrusion of the colon wall. Diverticulitis can present in about 10% to 25% of patients with diverticulosis. Diverticulitis can be simple or uncomplicated and complicated. Uncomplicated diverticulitis is without any associated complications. Complicated diverticulitis is associated with the formation of abscess, fistula, bowel obstruction, or frank perforation. Diverticulitis has conventionally been known and treated as a primarily surgical illness, but this has transitioned to be a medically managed entity even in its most acute phase.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Risk factors that increase the chances of developing diverticulitis are the same as those related to diverticulosis. Diet appears to play a significant role. Low fiber, high fat, and red meat diets may increase the risk for development of diverticulosis and possible diverticulitis. Obesity and smoking are known to increase the potential for both diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Finally, exposure to some drugs including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, and opiates are associated with diverticulitis. Conversely, exposure to statin drugs may decrease the incidence of symptomatic diverticulitis. Despite a common popular belief, nuts, seeds, and popcorn are not associated with increased risk of diverticulosis, diverticulitis, or diverticular bleeding.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Diverticulosis is present in approximately 60% of people older than 60 years. Diverticulitis occurs in about 10% to 25% of patients with diverticulosis. According to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest, all-payer inpatient care database in the United States revealed that there was 26% increase in hospitalizations for acute diverticulitis and a 38% increase in elective operations from 1998 through 2005. It further shows that young patients (18 to 44 years) are more likely to be admitted to the hospital than older patients (45 to 74 years). This trend is likely due to prompt diagnosis and improvement in diagnostic testing modalities. Western nations are overwhelmingly likely to have left-sided diverticulosis, whereas those of Asian descent are likely to have the right-sided disease. Across the world, the mean age for admission for acute diverticulitis is 63 years old. Though the disease was initially noted to be more prevalent in males, more recent data shows that the distribution of diverticulitis is equal in both males and females. Diverticulitis more commonly occurs in men younger than the age of 50 and women 50 to 70 years old. Diverticulitis occurring in patients over the age of 70 are more likely to be female.[6]

Pathophysiology

Diverticulitis is the result of microscopic and macroscopic perforations of the diverticular wall. Previously, practitioners thought that obstruction of colonic diverticulum with fecaliths led to increased pressure within the diverticulum and subsequent perforation. They now theorized that increased luminal pressure is due to food particles that lead to erosion of the diverticular wall. This causes focal inflammation and necrosis of the region, causing perforation. Surrounding mesenteric fat may easily contain micro-perforations. This can result in local abscess formation, fistulization of adjacent organs, or intestinal obstruction. Ultimately, frank bowel wall perforations can lead to peritonitis and death without rapid diagnosis and treatment.[7]

History and Physical

Clinical manifestation of acute diverticulitis varies depending on the severity of the disease. Patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis typically present with left lower quadrant abdominal pain, reflecting that propensity of left-sided disease in Western nations. However, patients of Asian descent present with predominantly right-sided abdominal pain. The pain can be constant or intermittent. Change in bowel habits, either diarrhea (35%) or constipation (50%), can be associated with abdominal pain. Patients may also experience nausea and vomiting, possibly secondary to bowel obstruction. Fever is not uncommon in patients with abscesses and perforation. Dysuria, frequency, and urgency can occur in patients when the inflamed portion of the bowel comes into direct contact with the bladder wall, which is called as sympathetic cystitis.

On physical examination, tenderness to palpation over the area of inflammation is almost always present due to irritation of the peritoneum. A mass may be felt in approximately 20% of patients if an abscess is present. Bowel sounds are usually hypoactive but can be normoactive. Patients can present with peritoneal signs (rigidity, guarding, rebound tenderness) with bowel wall perforation. On the other hand, fever is almost always present, but hypotension and shock are uncommon.

Evaluation

Diagnosis of acute diverticulitis can be made clinically based on history and physical examination alone. However, clinical diagnosis can be inaccurate in 24% to 68% of cases. Hence, laboratory and radiological tests play an important role in the accurate diagnosis of acute diverticulitis. Laboratory tests may show leukocytosis and elevation of acute phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). The radiological test of choice for acute diverticulitis is CT of the abdomen and pelvis, preferably with water-soluble oral or rectal (if significant nausea and vomiting) contrast and intravenous contrast provided there be no contraindications. The sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value of a CT scan have been reported as greater than 97%. Typical findings of acute diverticulitis in CT scans include bowel wall thickening, pericolic fat stranding, pericolic fluid, and small abscesses confined to the colonic wall as well as contrast extravasation, indicating intramural sinus and fistula formation.[8]

Abdominal ultrasound can accurately diagnose acute diverticulitis, with comparative sensitivity (84% to 94%) and specificity (80% to 93%) as of CT. However, ultrasound (US) results are highly operator dependent, and use is limited despite encouraging data, lower cost, and easy availability. MRI is another possible diagnostic modality. Due to cost and no direct comparison of sensitivity or specificity, CT is usually preferred. Radiographs of the abdomen will probably only show nonspecific abnormalities such as bowel gas; however, if the patient has an intestinal obstruction, air-fluid levels can be present.

Endoscopy should be avoided in suspected acute diverticulitis due to an increased risk of perforation. It is recommended that a colonoscopy is performed approximately six to eight weeks after symptoms have resolved to rule out malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or possibly colitis if the patient has not had a recent colonoscopy.

Treatment / Management

Upon clinical presentation, acute diverticulitis can be managed with either outpatient or inpatient care. According to American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, a patient who cannot tolerate oral intake, is excessively vomiting, shows signs of peritonitis, is immunocompromised, or at an advanced age should be hospitalized. In the absence of these conditions, and if appropriate prompt follow-up can be established, acute diverticulitis can be managed on an outpatient basis. It is reported that success rate of outpatient management is about 94% to 97%. The standard of outpatient care includes bowel rest, increase fluid intake, and oral antibiotic therapy (single or multiple drug regimen) that covers gram-negative rods and anaerobic bacteria. The most common regimen used in the United States consists of quinolones (ciprofloxacin) or sulfa drugs (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) in combination with metronidazole (or clindamycin, if the patient is intolerant to metronidazole) or single agent amoxicillin-clavulanate for 7 to 10 days.[8][3][9]

Inpatient management of diverticulitis requires intravenous antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and pain management. Again, antibiotics should cover gram-negative rods and anaerobes and be given for three to 5 days before switching to oral antibiotics for a ten to 14-day course. Bowel rest is preferred in patients requiring inpatient admission. Typically, defervescence and improvement in leukocytosis should be observed for two to four days of hospitalization, if not an alternative diagnosis or complications should be suspected. Prompt surgical evaluation should be considered.

About 15% patients with acute diverticulitis develop an abscess, specifically pericolonic and intra-mesenteric. Clinically, abscess formation should be suspected if fever and leukocytosis do not subside despite adequate intravenous (IV) antibiotics. On physical exam, a tender abdomen and tender mass suggest possible abscess formation. Abscesses that are less than 2 cm to 3 cm can be treated conservatively with IV antibiotics. Large abscesses should be drained percutaneously with CT guidance.

Fistula formation is another complication of acute diverticulitis. It is reported that less than 5% develops fistula; however, it has been found in about 20% of patients who undergo surgery for diverticulitis. The most common fistula is colovesicular fistula which occurs in about 65% of cases. Fecaluria is pathognomonic for colovesicular fistula. Surgical repair of the fistula with primary anastomosis is the treatment of choice. Colovaginal, coloenteric, colouterine, colourethral, and colocutaneous are other possible fistulae seen in acute complicated diverticulitis.

Partial bowel obstruction or pseudo-obstruction due to colonic ileus can occur as well, which can be managed conservatively. Complete bowel obstruction is rare in acute diverticulitis. Free perforation, if it occurs, should be managed surgically.

Differential Diagnosis

- Chronic mesenteric ischemia

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with diverticulitis depends on age at presentation, the presence of comorbidity and severity of the disease. In general, younger people tend to have a higher morbidity as they never suspect they have the disorder and often present late. In addition, patients who are immunocompromised tend to have high morbidity and mortality.[10]

Complications

- Pelvic abscess

- Intestinal perforation

- Bowel fistula

- Peritonitis

- Bowel obstruction

- Sepsis

- Bleeding per rectum

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After recovering from diverticulitis, the patient must be examined to rule out a malignancy. Options for investigation of the colon include colonoscopy, CT scan or a barium enema.

The patient should start a high-fiber diet, drink ample water, maintain a healthy weight and exercise.

Deterrence and Patient Education

A high-fiber diet can prevent diverticulosis.

Pearls and Other Issues

As previously stated, approximately 15% of patients with acute diverticulitis develop complications. Twenty percent to 50% of patients develop recurrent episodes of diverticulitis. Having multiple episodes does not appear to increase the risk for complications directly. It may increase the risk of fibrosis, leading to stricture formation and subsequent obstruction. Some patients, approximately 20%, will experience chronic abdominal pain due to either irritable bowel syndrome or chronic low-grade diverticulitis. These patients may be referred for elective colectomy for symptom control. Elective operations for diverticulitis have increased by approximately 30% since 1998.

The mortality rate in uncomplicated diverticulitis is negligible with appropriate conservative therapy. Complicated diverticulitis requiring surgery may lead to death in approximately 5% of patients. Perforation of the bowel with resulting peritonitis increases the risk of death to 20%.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acute diverticulitis has enormous morbidity and while there are no universal guidelines, expert opinion recommends an interprofessional approach for diagnosis and management. The disorder needs to be staged radiologically. In addition, the patient needs a dietary consult regarding a high-fiber diet. Nurses need to assist in educating the patient on following dietary restrictions. An infectious disease consultant and a gastroenterologist need to determine the duration of antibiotic therapy and a general surgeon is necessary to develop a protocol for management of any pelvic abscess. Finally, a general or colorectal surgery should determine the proximal levels of colon resection but the amount of clear proximal margin needed remains unknown. Because the risk of colon cancer in patients with acute diverticulitis is slightly increased, a screening program has to be established.[11][12] [13] (Level III)

Outcomes

Many cases studies reveal that the majority of patients treated for acute diverticulitis do not have a recurrence after initial medical treatment. However, in patients with recurrence, surgical excision of the diseased bowel is recommended, especially in patients over the age of 50. (Level V) Finally, the decision to perform laparoscopic or open surgery for managing acute diverticulitis remains debatable. One study showed no difference in postoperative morbidity between the two. [2][14](Level III) Randomized clinical studies are needed to determine which surgery and what type of surgery is ideal for patients with acute diverticulitis.