Introduction

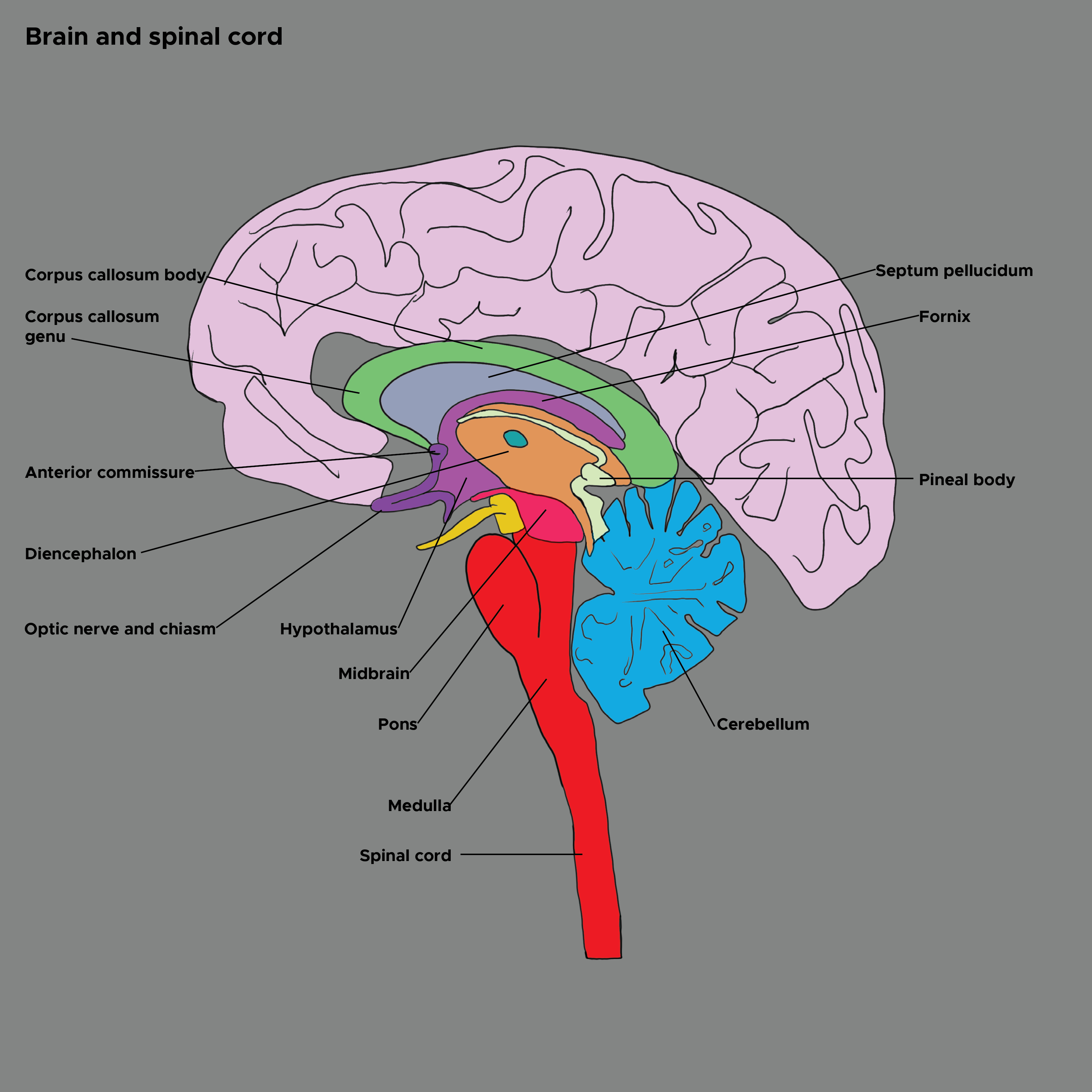

Landmarks defining the regions of the hypothalamus include the lamina terminalis, pituitary gland, mammillary bodies, and superior hypothalamic sulcus (see Figure. The Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis). The hypothalamus is a bilateral collection of nuclei divided into 3 zones surrounding the third ventricle and the mammillary bodies. The nuclei in the periventricular zone generally regulate the endocrine system, and the nuclei in the medial and lateral zones regulate autonomic and somatic behavior. The hypothalamus is centrally located in the brain, and it connects to the brainstem via the dorsal longitudinal fasciculus, cerebral cortex via the medial forebrain bundle, hippocampus via the fornix, amygdala via the stria terminalis, thalamus via the mammillothalamic tract, pituitary via median eminence, and retina via the retinohypothalamic tract.

Structure and Function

The hypothalamus is a high-level sensory integration and motor output area that maintains homeostasis by controlling endocrine, autonomic, and somatic behavior; it receives internal stimuli via receptors for circulating hormones. The blood-brain barrier is particularly permeable at the subfornical organ and organum vasculosum around the hypothalamus, allowing blood osmolarity sensation. When osmolarity increases during dehydration, the antidiuretic hormone (ADH) causes renal water reabsorption. The hypothalamus senses external stimuli via the spinothalamic tract carrying somatic sensory information, particularly pain. The hypothalamus is involved in limbic sensory integration via the fornix and mammillothalamic tract in the Papez circuit and the stria terminalis connection to the amygdala. Cortex-level sensory perceptions are received via the medial forebrain bundle. The retinohypothalamic tract carries light signals to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, regulating the diurnal pattern of hormone release. Integrating these inputs at the level of the hypothalamus leads to appropriate physiologic and behavioral responses that maintain life across time.[1]

The hypothalamus output regulates the endocrine, autonomic, and somatic systems. The area inferior to the thalamus has 11 unique nuclei. The paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei both produce the peptides oxytocin and ADH, which are released from neuronal axons into the capillaries of the posterior pituitary. These are both hormones and neurotransmitters. Oxytocin in systemic circulation controls uterine contraction during labor and milk is let down during breastfeeding. Systemic ADH increases the translocation of aquaporin to the apical membrane in the renal distal convoluted tubules, increasing water reabsorption during dehydration. These hormones share a common peptide, which means that excess oxytocin, or synthetic oxytocin used in labor and delivery, can activate renal ADH receptors. Thus hyponatremia is a side effect of synthetic oxytocin. ADH also causes vasoconstriction to increase blood pressure in severe hypovolemia and release von Willebrand factor from the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells to control bleeding. Furthermore, both oxytocin and ADH, acting as central neurotransmitters, are involved in pair bonding.[2]

Preoptic, Anterior, and Posterior Nuclei

The preoptic, anterior, and posterior nuclei regulate body temperature by decreasing the sympathetic tone of skeletal muscle, increasing the sympathetic tone of the skin, dilating capillaries, and improving heat exchange with the exterior. Males and females differ in the distribution of estrogen receptors in the preoptic nucleus, influencing sexual and maternal behavior.[3]

Suprachiasmatic Nucleus

The suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates hormone secretion and behavior diurnally according to light input through the eyes. Twenty-four–hour oscillations of clock transcription factor activity and action potential frequency increase locomotor activity during the day and decrease it at night—moreover, cortisol peaks around sunrise, and growth hormone peaks near midnight. Most myocardial infarctions happen in the early morning due to the stress hormone cortisol peak, which raises blood pressure.[4]

Ventromedial Nucleus

The ventromedial nucleus regulates feeding behavior. Destruction of this area causes hyperphagia, such as that seen in Prader-Willi syndrome. Satiety, as perceived by this area, leads to decreased eating. The dorsomedial nucleus controls rage behavior. Lack of satiety can lead to aggression. The lateral hypothalamus perceives hunger and increases eating. Destruction of the lateral area causes anorexia.[5]

Arcuate Nucleus

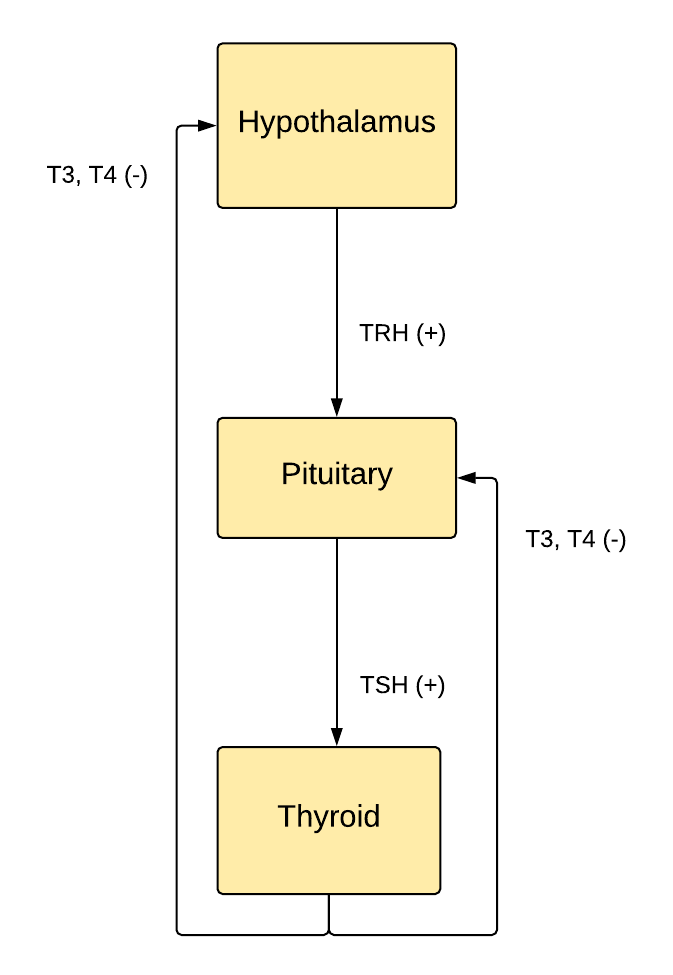

The arcuate nucleus releases hormones secreted by axon terminals into the hypothalamohypophysial venous portal system to control anterior pituitary hormone release. The corticotropin-releasing hormone causes the anterior pituicytes to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into capillaries, which drain into the cerebral venous system. ACTH travels through systemic circulation to stimulate the adrenal cortex (zona reticularis) production of the stress-response hormone cortisol. Given its diversity of inputs, the hypothalamus enables the body to respond to physiological and psychological stressors. Again, cortisol production varies throughout a 24-hour day, with the highest level around sunrise and the lowest around sunset due to the interconnections between the arcuate and suprachiasmatic nuclei. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone leads to systemic TSH secretion, increasing the synthesis and release of thyroid hormone to regulate metabolism. The hypothalamus senses body energy stores in part by receptors for the adipocyte hormone leptin. When reserves are low, the hypothalamus decreases metabolism by decreasing the thyroid hormone.

Pulsatile GnRH leads to increased release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Continuous GnRH causes decreased LH and FSH release. LH stimulates the male testes to produce testosterone and the female ovaries to produce estrogen. These hormones lead to secondary sexual development in males and females, respectively. A surge in LH causes ovulation. FSH stimulates male spermatogenesis and female oocyte maturation. Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) releases growth hormone (GH), which stimulates tissue growth and metabolism. Somatostatin decreases GH release and opposes GHRH. Dopamine inhibits prolactin secretion as part of the hypothalamohypophysial dopamine circuit. Phenothiazine antipsychotics interrupt this pathway, leading to a galactorrhea side effect. Many of these hormones can be manipulated clinically by synthetic analogs. These are treatments for diseases like uterine leiomyomas, anovulation, hypogonadism, breast and prostate cancer, birth control, and acromegaly.[6]

Mamillary Nucleus

The mamillary nucleus contributes to the limbic system as part of the Papez circuit. It is also involved in memory formation and controls exploratory behavior.[7] Bilateral mamillary body lesions are characteristic of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, which features anterograde and possibly retrograde amnesia.

The hypothalamus sits atop a motor hierarchy, which includes the cerebral cortex, limbic system, brainstem, and spinal cord motor neurons. The hypothalamus integrates internal and external information about the organism's state and governs action patterns to maintain homeostasis across the lifespan. The sensory areas of the cerebral cortex provide abstract sensory perceptions. The limbic system provides potent emotional stimuli. The spinohypothalamic tract provides pain and temperature information. The brainstem provides serotonin and norepinephrine. The hypothalamus integrates these stimuli and activates action patterns and postures in the cerebral cortex and brainstem. These signals travel through the spine to the muscles and produce behaviors (see Image. Brain and Spinal Cord).[8]

Embryology

The notochord induces neurulation around week 3 of gestation. Noggin, chordin, bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), and fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) are some of the genes involved. The neural tube forms from the ectoderm and closes by week 6. The rostral end is the lamina terminalis. The neural tube differentiates into 3 primary vesicles the forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord. The forebrain differentiates into the telencephalon and diencephalon, the midbrain continues to be the mesencephalon, and the hindbrain becomes the metencephalon and myelencephalon. These structures continue to differentiate into adult brain structures. The hypothalamus and posterior pituitary are derived from the diencephalon. Furthermore, the neural tube separates into the alar (sensory) and basal (motor) plates, separated by the sulcus limitans. The hypothalamus is derived from interneurons in the alar plate, making it a sensory and motor integration center.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The hypothalamus is supplied by the circle of Willis, which surrounds it inferiorly, the anteromedial branches of the anterior cerebral artery, the posteromedial branches of the posterior communicating artery, and the thalamo-perforating branches of the posterior cerebral artery. Venous drainage is largely via the circle of intercavernous sinuses. The hypothalamo-neurohypophysial portal system is a capillary plexus that transmits the releasing hormones from the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary.

Astroglia podocytes form the blood-brain barrier by wrapping podocytes around capillaries. These cells protect the brain from toxins in the blood and facilitate nutrient transport to the neurons. Astroglia also forms a system of microscopic perivascular channels permeating the brain that transmit cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-like lymphatic vessels. The system enables CSF to clear metabolic waste and distribute glucose, amino acids, lipids, and neurotransmitters. This system is most active during sleep, contributing to its restoration function. Arterial pulsation drives glymphatic flow, suggesting that exercise may also enhance it. Aging, brain trauma, and ischemia decrease CSF flow. Also, larger lymphatic vessels in the meninges help absorb interstitial fluid into the dural venous sinuses.[9][10]

Surgical Considerations

Anterior pituitary adenomas are the most common tumors affecting the hypothalamus. They may exert a mass effect that causes headaches and vision changes like bitemporal hemianopsia due to optic chiasm compression. They may produce hormones, causing endocrine diseases. Prolactinomas cause galactorrhea and suppress gonadotropins, leading to decreased libido and infertility. Growth hormone-producing tumors cause gigantism and acromegaly. ACTH-producing tumors cause Cushing Disease due to hypercortisolism. Gonadotropin-producing tumors can cause precocious puberty or hirsutism. The preferred approach for tumor removal is trans-sphenoidal. A complication is damage to the hypothalamus, which can cause osmotic, autonomic, or feeding dysregulation.[11] Complications of surgery include the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), central diabetes insipidus, and cerebral salt wasting.

Clinical Significance

The hypothalamus regulates feeding via the leptin and ghrelin pathways. Energy expenditure is regulated via the balance between proopiomelanocortin (POMC)/cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) and neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons in the arcuate nucleus. Leptin is a hormone produced by adipocytes in proportion to their energy reserves. High reserves mean high leptin. The arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus receives the signal, decreases feeding, and increases energy expenditure via the activity of POMC/ CART. These transmitters act on the nuclei responsible for feeding, increasing body temperature, metabolism, locomotor activity, and gonadotropin production. On the contrary, decreased fat reserves lead to increased feeding and cortisol (via the action of the transmitters NPY/AgRP within the hypothalamus) and decreased body temperature, metabolism, movement, and gonadotropin production. There is an ongoing investigation into the role of the MC4 receptor and leptin resistance in obesity.[12]

The hypothalamus is also responsible for the acute-phase immune response. White blood cells cause endothelial production of prostaglandin E2, which activates prostaglandin receptors in the paraventricular and preoptic nuclei. This causes fever by raising the body temperature setpoint, triggering a sympathetic response, and causing muscle contractions (shivering). Cortisol and hepatic acute-phase protein production are increased. These effects cumulate in the malaise and sick behavior typical of many illnesses.[13]

- Prolactin leads to lymphocyte survival and induces oligodendrocyte precursors to differentiate. Multiple sclerosis often improves during pregnancy.[14]

- The mammillary bodies are destroyed by thiamine deficiency, leading to Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff psychosis with prominent amnesia.[15]

- Cerebral salt wasting is a common complication of traumatic brain injury, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage. Findings include hypotonic hyponatremia and polyuria with increased urine sodium. Treatment is salt supplementation followed by fludrocortisone.

- SIADH is a complication of hypothalamic injury neurosurgery or AIDS. Findings include hypotonic hyponatremia, oliguria with increased urine sodium. Treatment is water restriction followed by hypertonic saline and then demeclocycline.

- Central diabetes insipidus is caused by hypothalamic injury, which decreases ADH production. Findings include polyuria without concentration. Desmopressin is the treatment.