Definition/Introduction

Change is inevitable in healthcare; however, nearly two-thirds of change projects fail for various reasons, including poor planning, unmotivated staff, ineffective communication, and widespread changes.[1] All healthcare providers, from the bedside to the boardroom, have a crucial role in ensuring effective change. Implementing best practices from change management theories can improve the likelihood of success and lead to better outcomes in practice.

Suppose a healthcare provider working in a hospital department has seen a rise in unwitnessed patient falls during shift changes over the past 3 months. Implementing evidence-based changes to the shift change process could help reduce these falls. However, departmental leadership has tried to address this issue twice in the last 3 months without success. Staff continue to revert to previous shift change protocols to save time, resulting in prolonged periods where patients are unmonitored. What strategies can departmental leadership and staff adopt to create lasting, positive changes that benefit both patients and employees?

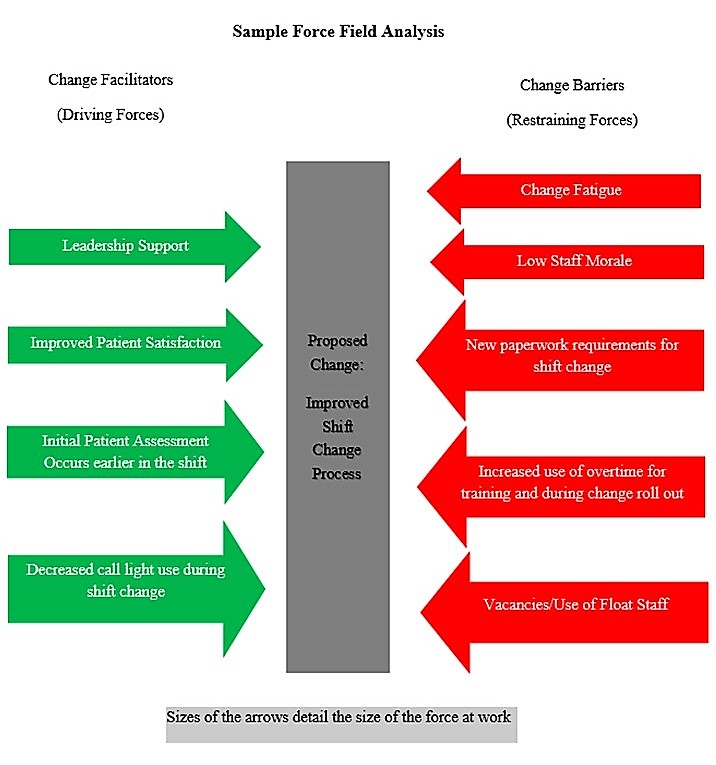

The answer may lie within the work of several change leaders and theorists. Although theories may seem abstract and impractical for direct healthcare practice, they are valuable for addressing common healthcare challenges. Lewin, an early change scholar, proposed a 3-step process to facilitate successful change.[2] Other theorists, such as Lippitt, Kotter, and Rogers, have built on Lewin’s original Planned Change Theory, contributing to a broader understanding of change management. Each theory has its unique strengths and weaknesses, but their commonalities can offer best practices for sustaining positive change (see Image. Sample Force Field Analysis in Change Management).

Lewin’s Theory of Planned Change includes the following change stages:

- Unfreezing: Understanding the need for change

- Moving: Initiating the process of change

- Refreezing: Establishing a new status quo [2]

Lippitt, expanding on Lewin’s original theory, developed the Phases of Change Theory, which includes the following change phases:

- Increasing awareness of the need for change

- Developing a relationship between the system and the change agent

- Defining the change problem

- Setting goals and action plans for achieving change

- Implementing the change

- Gaining staff acceptance and stabilizing the change

- Redefining the relationship of the change agent and the system [3]

Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model, developed in 1995, includes the following steps for effective change management:

- Create a sense of urgency for change

- Form a guiding change team

- Create a vision and plan for change

- Communicate the changed vision and plan with stakeholders

- Enable action by removing barriers to change

- Generate short-term wins

- Build on the change

- Anchor the change in the organizational culture [3]

Finally, Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation Theory outlines the following 5 phases of change:[4]

- Knowledge: Educating and communicating to inform staff about the change.

- Persuasion: Engaging change champions to pique interest among staff and encourage peer persuasion.

- Decision: Staff deciding whether to accept or reject the change.

- Implementation: Putting new processes into practice.

- Confirmation: Staff recognizing the value and benefits of the change and continuing to utilize the new processes.[4]

Issues of Concern

All change initiatives, whether large or small, progress through 3 key stages—pre-change, change, and post-change. Healthcare providers acting as change agents or champions during each stage should align their actions with relevant change theories. In the pre-change stage, a key step is involving stakeholders in problem identification, goal setting, and action planning. Early engagement of stakeholders is critical for gaining staff buy-in. Notably, it is also important to include staff from all shifts, including nights and weekends, to ensure peer change champions are available at all times.[5]

Rogers' change theory highlights the varying rates at which staff members adopt changes through innovation diffusion. During pre-change planning, change agents should assess their team to identify which category each staff member falls into. Rogers classified these groups as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.[4] He further defined these change acceptance categories as follows:

- Innovator: Enthusiastic about change and technology; often suggests new ideas for departmental improvements.

- Early adopter: Highly influential within the department; respected by peers for their leadership.

- Early majority: Prefer the status quo but follows early adopters once changes are announced.

- Late majority: Skeptical of change but accepts it once most others have; influenced by growing social pressure within the department.

- Laggard: Extremely skeptical; openly resists change.[4]

Most departmental staff likely fall into the early or late majority. Change agents should focus their initial education efforts on innovators and early adopters. Early adopters, in particular, are key change champions, as they play a crucial role in persuading both early and late majority staff to embrace change initiatives.[4]

A final key assessment for change leaders to incorporate is a force field analysis, a core element of Lewin's early change theory. This analysis involves evaluating the facilitators and barriers to change within the department. Change leaders should focus on reducing barriers through open communication and education while simultaneously reinforcing facilitators by recognizing staff efforts and offering incentives.

One of the biggest mistakes a change leader can make during implementation is failing to ensure staff follow new processes as intended. Consistent leader engagement throughout the change process greatly improves the likelihood of success.[5] Staff resistance is common during this stage. Change leaders may find it helpful to conduct another force field analysis during this phase to ensure no new barriers have emerged.[3] Strengthening change facilitators through staff engagement, recognition, and sharing short-term wins helps maintain momentum. As the change process progresses, some staff may need additional on-the-spot training to address knowledge gaps. Leaders must also continue monitoring progress toward goals by tracking metrics such as patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, fall rates, and chart audits.[3]

Once the change has become embedded in the department's culture, change leaders must periodically validate processes and seek staff feedback. Change agents can redefine their relationship with the team, adopting a less active role in maintaining the change. However, as leaders begin to relinquish control, staff members may gradually revert to old, negative behaviors. Periodic spot checks and ongoing data monitoring can help solidify the change as the department's new status quo. Change managers should celebrate achievements with staff and continue sharing evidence of success during meetings or through departmental communication boards.[5]

Clinical Significance

Change is inevitable but often slow to achieve. While change theories offer best practices for leadership and implementation, their application does not guarantee success. The change process is susceptible to various internal and external influences. Utilizing change champions from all shifts, conducting force field analyses, and maintaining regular supportive communication can enhance the likelihood of success.[5] Additionally, understanding how each staff member will likely respond to change based on the diffusion of innovation phases can guide leaders in tailoring their conversations to facilitate the transition in departmental processes.