Introduction

The primary function of the gastrointestinal tract is to supply nutrients to our bodies via the processes of ingestion, motility, secretion, digestion, and absorption; this occurs through complex coordination of digestive processes that are regulated by intrinsic endocrine and nervous systems. Although the nervous system exerts influence on many digestive processes, the GI tract is the largest endocrine organ in the human body and produces numerous mediators that play an integral role in regulating functions of the GI tract.

Cellular Level

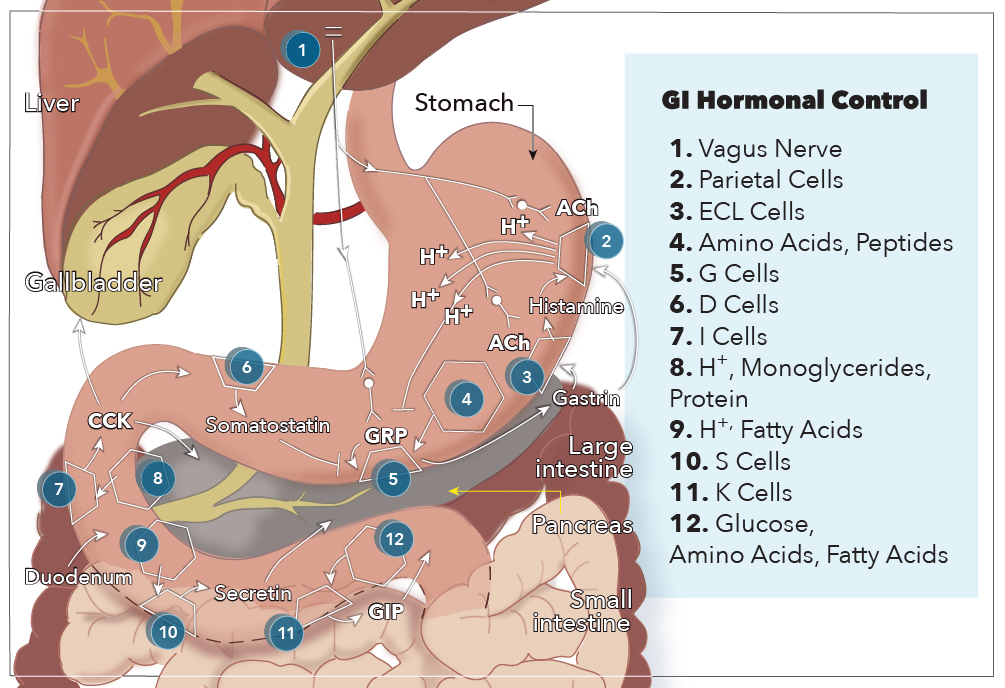

The GI hormones classify as endocrines, paracrine, or neurocrine based on the method by which the molecule gets delivered to its target cell(s). Endocrine hormones are secreted from enteroendocrine cells directly into the bloodstream, passing from the portal circulation to the systemic circulation, before being delivered to target cells with receptor-specificity for the hormone. The five GI hormones that qualify as endocrines are gastrin, cholecystokinin (CCK), secretin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), and motilin. Enteroendocrine cells also secrete paracrine hormones, but they diffuse through the extracellular space to act locally on target tissues and do not enter the systemic circulation. Two examples of paracrine hormones are somatostatin and histamine. Additionally, some hormones may operate via a combination of endocrine and paracrine mechanisms. These “candidate” hormones are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), pancreatic polypeptide, and peptide YY. Lastly, neurocrine hormones get secreted by postganglionic non-cholinergic neurons of the enteric nervous system. Three neurocrine hormones with significant physiologic functions in the gut are vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), gastrin release peptide (GRP), and enkephalins.[1]

Gastrointestinal hormones undergo synthesis in specialized cells of the GI tract mucosa known as enteroendocrine cells. Enteroendocrine cells are specialized endoderm-derived epithelial cells that originate from stem cells located at the base of intestinal crypts. These cells are dispersed throughout the GI mucosa, sprinkled in between epithelial cells from the stomach all the way through to the colon. Also, these enteroendocrine cells possess hormone-containing granules concentrated at the basolateral membrane, adjacent to capillaries, that secrete their hormones via exocytosis in response to a wide range of stimuli related to food intake. These stimuli include small peptides, amino acids, fatty acids, oral glucose, distension of an organ, and vagal stimulation.[2]

G cells secrete gastrin in the antrum of the stomach and the duodenum in response to the presence of breakdown products of protein digestion (such as amino acids and small peptides), distention by food, and vagal nerve stimulation via GRP. More specifically, phenylalanine and tryptophan are the most potent stimulators of gastrin secretion among the protein digestion products. The vagal nerve stimulation of gastrin secretion is unique because gastrin and motilin are the only hormones released directly by neural stimulation.

CCK is secreted from I cells in the duodenum and jejunum in response to acids and monoglycerides (but not triglycerides), as well as the presence of protein digestion products.

Secretin is secreted from S cells in the duodenum in response to H+ and fatty acids in the lumen. Specifically, a pH less than 4.5 signals arrival of gastric contents, which initiates the release of secretin.

GIP is secreted by K cells in the duodenum and jejunum in response to glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids. GIP is the only GI hormone with a response to all three macronutrient types, and newer studies suggest that changes in intraluminal osmolarity may be what stimulates GIP secretion.[3]

GLP-1 is also produced in the small intestine and secreted from L cells. The presence of hexose and fat stimulate its release. Pancreatic polypeptide and peptide YY are secreted by protein and fat, respectively, although their functions are still relatively unknown.

Development

The enteroendocrine cells responsible for synthesizing and secreting GI hormones derive from pluripotent intestinal stem cells in the intestinal crypts. As these stem cells move up the crypt-villus axis, they express specific transcription factors that give rise to absorptive enterocytes or cells of secretory lineages (Paneth cells, goblet cells, and enteroendocrine cells). The sequential expression of three basic loop helix loop (bHLH) transcription factors (Math1, Neurogenin3, and NeuroD1) is involved in specifying the enteroendocrine cell lineage. Math1 expression specifies cells that are fated for the secretory progenitor lineage and segregates them from the absorptive enterocyte lineage. Subsequent expression of Neurogenin3 represents a secretory progenitor cell that has initiated differentiation into the endocrine cell lineage. Lastly, NeuroD1 expression induces cell cycle arrest and commits a cell to an enteroendocrine fate.[4][5]

In addition to the bHLH transcription factors, numerous paired and homeodomain genes, including Isl-1, Pdx1, Nkx6.1, Nkx2.2, Pax4, and Pax6, are involved in differentiation of enteroendocrine cells into the distinct subtypes of hormone-secreting cells scattered throughout the GI tract. These subpopulations include G cells, I cells, S cells, K cells, Mo cells, L cells, and D cells, which are primarily responsible for secreting gastrin, CCK, secretin, GIP, motilin, GLP-1, and somatostatin, respectively. Interestingly, many subtypes of enteroendocrine cells are able to secrete multiple hormones, but the expression of hormonal genes is controlled by location in the GI tract.[6]

Gastrointestinal hormones are composed of polypeptides that can divide into two structurally homologous families that include the hormones responsible for a majority of regulation of GI function. The first hormone family consists of gastrin and CCK because both hormones share an identical 5 C-terminal amino acid sequence, also known as “pentagastrin.” This sequence includes the tetrapeptide that is minimally required for gastrin activity but is only about one-sixth as potent as the entire 17-amino acid gastrin peptide. Gastrin also exists in a 34-amino acid form called “big” gastrin which gets secreted during the inter-digestive period. During meal ingestion, the 17-amino acid form of gastrin, also called “little” gastrin, is secreted. Although each form of gastrin has its own distinct biosynthetic pathway, the mediation of the action of both gastrin peptides is via binding of cholecystokinin (CCK-2) receptors. The other member of the gastrin family, CCK, is a 33-amino acid peptide that includes the pentagastrin sequence and the C-terminal tetrapeptide sequence necessary for minimal gastrin activity; this enables CCK to demonstrate activity on gastrin (CCK-2) receptors, although it mediates a very weak stimulation of gastric acid secretion. Furthermore, the minimally active fragment for CCK activity is its C-terminal heptapeptide, which acts on CCK-1 receptors to mediate gallbladder contraction. Gastrin can also act on the CCK-1 receptor, but each hormone is more potent at its own receptor than those of its homolog.

The second hormone family consists of secretin, glucagon, GLP-1, and GIP. Secretin has 27 amino acids and is structurally similar to glucagon, which has 29 amino acids. However, in contrast with the gastrin-CCK family, all amino acids in the polypeptide are necessary for biological activity, and these two polypeptides only share 14 common amino acids. Glucagon derives from a 180-amino acid precursor peptide called proglucagon, which undergoes tissue-specific post-translation processing to produce different peptides in different cell types. Proglucagon is cleaved to form glucagon in the pancreas, while in the intestines, proglucagon undergoes processing to produce a 30-amino acid peptide called GLP-1. GIP is 42 amino acids long but only shares nine amino acids with secretin and 16 amino acids with glucagon.[7]

Organ Systems Involved

The digestive system is the primary site of action for most GI hormones and related polypeptides. The stomach is the primary site of gastrin production with some D-cells also populating the duodenum. Somatostatin and histamine are also produced in the stomach by enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which is an enteroendocrine cell subtype. The small intestines, namely the duodenum and jejunum handle secretion of CCK, secretin, GIP, and motilin.

Function

The two gastrointestinal hormone families discussed above are responsible for most of the regulation of gastrointestinal function. The main actions of the gastrin-CCK family and the secretin family of hormones are listed below.

Gastrin

- Stimulates H+ (acid) secretion by parietal cells in the stomach

- Trophic (growth) effects on the mucosa of the small intestine, colon, and stomach

- Inhibits the actions of Secretin and GIP

- Inhibited by H+

CCK

- Contraction of the gallbladder with simultaneous relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi

- Inhibits gastric emptying

- Stimulates secretion of pancreatic enzymes: lipases, amylase, and proteases

- Secretion of bicarbonate from the pancreas

- Trophic effects on the exocrine pancreas and gallbladder

Secretin

- Inhibits gastrin, H+ secretion, and growth of stomach mucosa

- Stimulates biliary secretion of bicarbonate and fluid

- Secretion of bicarbonate from the pancreas

- Trophic effect on the exocrine pancreas

GIP

- Stimulation of insulin secretion

- Induces satiety

- In large doses, decreases gastric acid secretion

- In large doses, decreases the motor activity of the stomach and therefore slows gastric emptying when the upper small intestine is already full of food products.

- Stimulates the activity of lipoprotein lipase in adipocytes

- Protects beta-cells of the pancreas from destruction by apoptosis

GLP-1

- Decreases gastric emptying

- Induces satiety

- Increases sensitivity of pancreatic beta-cells to glucose.

Motilin

- Increases gastrointestinal motility by stimulating the “migrating motility” or “myoelectric complex” that moves through the fasting stomach and small intestines every 90 minutes. This cyclical release and action get inhibited by the ingestion of food. Not much is known about this peptide, except for this essential function.

Mechanism

The release of GI hormones is in response to input from G-protein-coupled receptors that detect changes in luminal contents. Some of these receptors only respond to selective luminal substances and subsequently release GI hormones from their respective enteroendocrine cells through unknown mechanisms. Overall, gastrointestinal hormones manage a diverse set of actions in the body including:

- Contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle wall and sphincters

- Secretion of enzymes for digestion

- Secretion of fluid and electrolytes

- Trophic (growth) effects on tissues of GI tract

- Regulating secretion of other GI peptides (i.e., somatostatin inhibits secretion of all GI hormones)

To better understand how these actions are carried out by GI hormones, it is best to use gastrin’s functions as an example. Gastrin is an interesting hormone because it acts through two mechanisms that ultimately increase the secretion of gastric acid (hydrogen ions) into the stomach. The first mechanism involves gastrin binding to CCK-2 receptors on parietal cells, causing increased expression of K/H ATPase enzymes that are directly responsible for increased hydrogen ion secretion into the stomach. The second mechanism is mediated by enterochromaffin-like cells, which secrete histamine in response to activation by gastrin. Histamine then binds H2 receptors on nearby parietal cells, which further stimulates secretion of hydrogen ions. In addition to stimulating ECL cells to produce acid, gastrin also stimulates these parietal cells and ECL cells to proliferate.

Related Testing

Gastrin levels are routinely measured to diagnose Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which is characterized by gastrin-producing tumors in the duodenum or pancreas that result in recurrent, refractory peptic ulcers and diarrhea. A gastrin level 10 times the upper limit of normal (approximately 1000 pg/mL) plus a gastric pH below 2.0 is diagnostic of Zollinger-Ellison (ZE) syndrome.[8]

Pentagastrin injection is used to diagnose carcinoid syndrome because administration will induce symptoms in patients who present with minimal or inconsistent symptoms. Additionally, the pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin test for patients with normal calcitonin levels who have symptoms suspicious for medullary thyroid carcinoma.

Cholecystokinin is used for diagnostic radiography examinations of the gallbladder, called biliary scintigraphy, for patients with suspected gallbladder disease, and also has utility in manometry for patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Secretin is used as an adjunct with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for diagnostic testing of pancreatic secretion and potential ductal obstruction.

Pathophysiology

Gastrin secretion increases in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, infection with Helicobacter pylori, and chronic use of H2 blockers and/or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome have a gastrin-secreting tumor (gastrinoma) in the duodenum or pancreas that results in excess gastrin secretion. Predictably, these patients will have increased H+ secretion and hypertrophic gastric mucosa because of gastrin’s trophic effects. Furthermore, the excess acid lowers the luminal pH so significantly that pancreatic lipase will become inactivated, causing patients to experience steatorrhea due to fat malabsorption. In addition to measuring serum gastrin levels, the best diagnostic confirmation of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is with the secretin stimulation test using 0.4 micrograms/kg via intravenous infusion. Since secretin inhibits gastrin release in normal mucosa and stimulates gastrin release by gastrinoma cells, an increase in circulating gastrin levels of greater than 120 pg/mL over basal fasting levels suggests Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a common cause of elevated gastrin secretion (hypergastrinemia) with normal or increased gastric acid production. However, it is possible to have hypergastrinemia with decreased acid production.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative organism that directly damages gastric glands and parietal cells by infiltrating the gastric mucosa. This destruction results in decreased acid production and secondary hypergastrinemia due to lack of negative feedback of G cells.

Since H2 blockers and PPIs inhibit secretion of hydrogen ions by parietal cells in the stomach, patients who chronically take these medications will experience secondary hypergastrinemia in response to lack of negative feedback from gastric acid production. Due to the trophic effects of gastrin, this also raises concern for the development of cancer arising from ECL cells, called carcinoid tumors.

Clinical Significance

Treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome consists of surgical and non-surgical options. Currently, surgery is the only curative option for gastrinomas. Specifically, a duodenectomy for duodenal gastrinomas since multiple tumors tend to be present, and excision/enucleation for pancreatic tumors.

Octreotide is an octapeptide that pharmacologically mimics the actions of natural somatostatin. Interestingly, it is a more potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon and insulin secretion, than natural somatostatin, and even has a longer half-life. These properties make Octreotide indicated for the treatment of growth-hormone producing tumors (such as in acromegaly and gigantism), pituitary tumors that secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone, symptoms of diarrhea and flushing from carcinoid syndrome, and diarrhea in patients with VIP-secreting tumors (VIPomas). Additionally, it is often given parentally to manage acute hemorrhage due to esophageal varices caused by liver cirrhosis. It has poor gut absorption; therefore, parenteral administration is necessary.

GLP-1, along with GIP, is a member of the incretin family of peptides and hormones. Incretins are released in response to eating and stimulate a decrease in blood glucose levels via augmenting insulin secretion from the pancreas. In fact, incretins are so powerful that they are directly responsible for higher serum insulin secretion and blood levels in response to oral glucose versus intravenous glucose administration. Furthermore, synthetic GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs have shown a therapeutic benefit for patients with type 2 diabetes, mainly because GLP-1 will stimulate the release of insulin regardless of blood glucose levels. GLP-1 also mediates the “ileal brake,” which is the inhibition of gastric and pancreatic secretion and motility that occurs in response to an increased amount of nutrients detected in the ileum; this serves as a critical inhibitory feedback mechanism that has strong implications for slowing gastric emptying and promoting satiety in diabetes patients and overweight patients.[9]