Introduction

The neck refers to the collection of structures that connect the head to the torso. It is a complex structure of many bones, muscles, nerves, blood vessels, lymphatics, and other connective tissues. The cervical spine is the bony part of the neck. Its primary function is to support the skull while still allowing for movement. It is the most flexible part of the spine. This flexibility allows for large movements to scan our surroundings. Most sensory inputs occur at the head; thus, proper neck movement is vital to survival.

The neck also acts as a conduit for the brain to communicate with the rest of the body. Motor and sensory information and nutrients from the body to the head and vice versa must all pass through the neck. The neck is also subject to stress and susceptible to injuries. Given its importance, injuries can sometimes have significant consequences for our functionalities and are even fatal.

Structure and Function

The cervical spine is composed of seven vertebrae. Cervical vertebrae C1 and C2 are known as "atypical" vertebrae due to the presence of unique bony structures designed to support and move the skull. While the cervical spine can undergo flexion, extension, rotation, and side-bending, each individual cervical joint has a primary motion.

C1, the atlas, has no spinous process and articulates with the occipital condyles of the occiput bone of the skull, forming the occipital-atlanto (OA) joint. The OA joint connects the skull to the neck, providing attachment points for some neck muscles. It also functions to bear the weight of the skull, providing support. The primary motions of the OA joint are flexion and extension.

C2, the axis, articulates superiorly with C1 via a unique bony structure called the dens or odontoid process. The dens projects up from the vertebral body and articulates with the atlas. The dens permits pivoting motion and allows a greater range of motion in rotating the head laterally.

Vertebrae C3 through C7 are known as "typical" cervical vertebrae. The primary motion of the upper portion of the lower cervical unit (C2-C4) is rotation. The primary motion of the lower portion of the lower cervical unit is side-bending. The description of all spinal and vertebral movements is relative to motions of their anterior and superior surfaces.[1]

- Cervical flexion: bending the head forward towards the chest.

- Cervical extension: bending the head backward with the face towards the sky.

- Cervical rotation: turning the head to the left or the right.

- Cervical side-bending: tipping the head to the side or touching an ear to the ipsilateral shoulder.

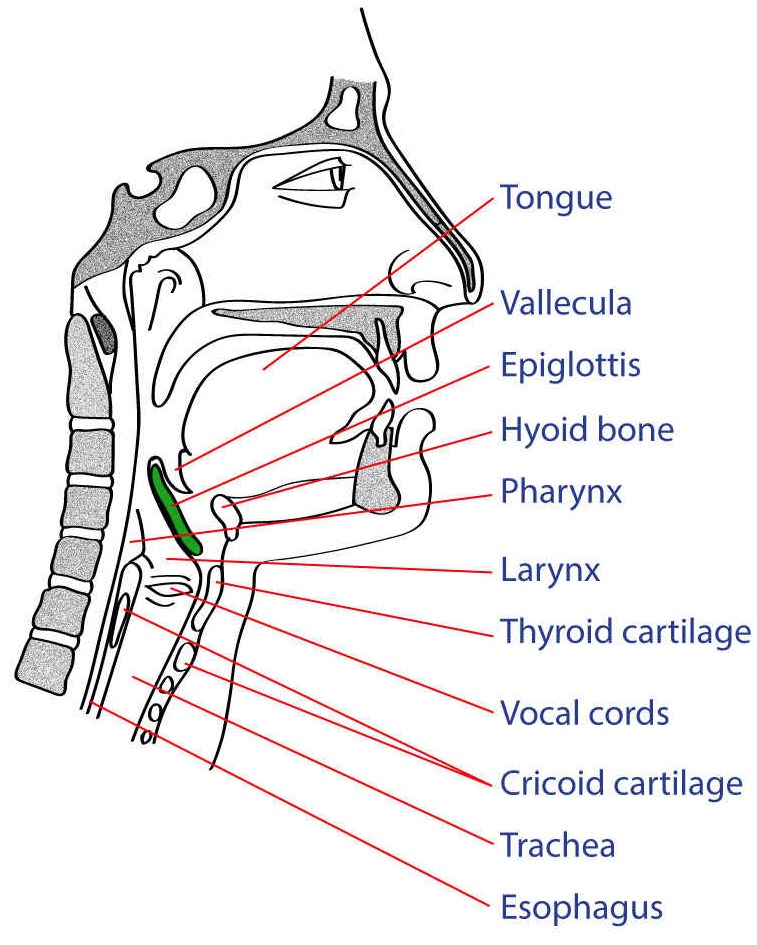

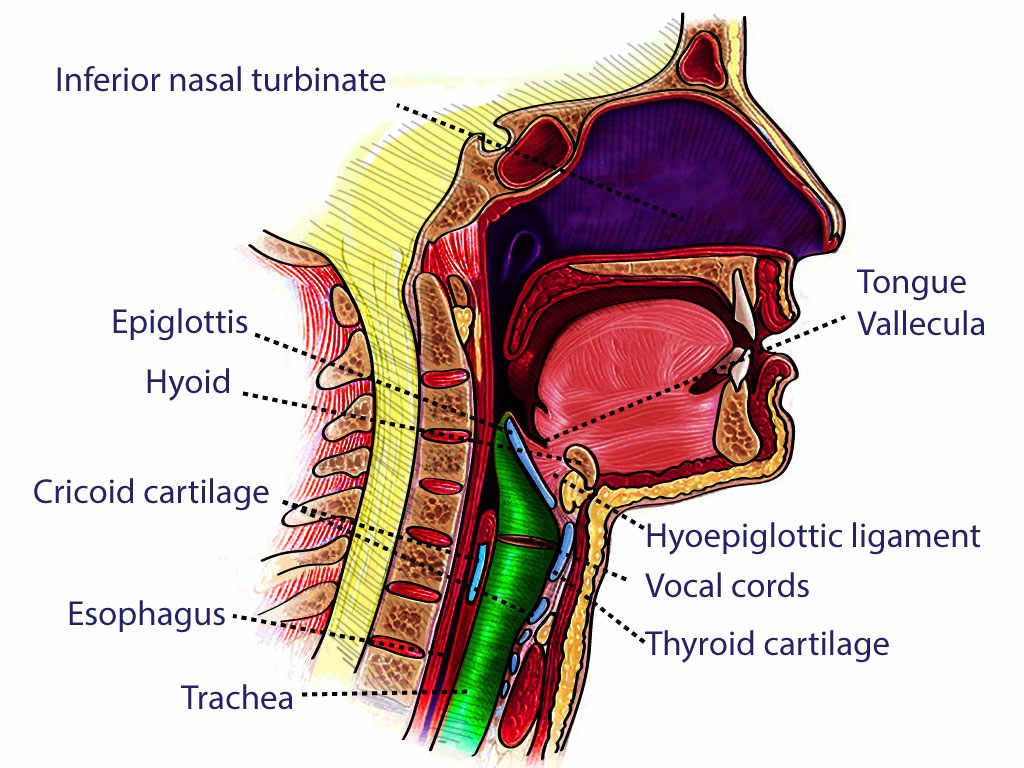

The function of the cervical spine is to stabilize and maintain the head in a position that allows our eyes to be parallel to the ground.[2] This is crucial for the vestibular function, which assists in balance. The cervical spine allows large movements to scan our surroundings and adjust to interact with our environment. It also aids in swallowing and helps to elevate the rib cage during inhalation. The vertebral bodies protect the spinal cord and vertebral arteries, and the muscles of the neck protect other neurovascular structures necessary for sustaining life. Any interruption of proper neck function can lead to a critical state; neck function is usually the first thing evaluated in any emergency.

Embryology

The notochord, the most primitive form of the axial skeleton, appears during the third week of development. The notochord evolves into a segmented vertebral structure in three different stages. The first stage consists of embryonic mesenchymal tissue. The second stage occurs when these mesenchymal cells differentiate and develop into chondrogenic cells. By the beginning of the third month of development, the cartilaginous structure has begun to ossify into the future vertebral segments. The mesoderm is also responsible for skeletal muscle, bone, and connective tissue.[3]

The development of the vertebral column begins with the notochord. This structure is located beneath the neural tube, which gives rise to the brain and spinal cord. The cranial end of the notochord forms first, and the development of the notochord then proceeds in a caudal direction. When fully developed, the definitive regions of the spinal cord are the telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon (midbrain), metencephalon (pons) with the cerebellum (rhombencephalon), myelencephalon (medulla oblongata) and myelon (spinal cord).

The vertebrae are formed from the sclerotomal portion of the somites (soma is Greek for "body"). The 42 pairs of somites are composed of the paraxial mesoderm of the embryo.[4] Sclerotomes, myotomes, symetotomes, and dermatomes are all subdivisions of somites. Somites give rise to the muscles, the vertebral column, and dermatomes (the sensory supply from a given spinal cord nerve).

The somitic scleroderm forms the vertebrae. Sclerodermal cells pass around the notochord and spinal cord to join with cells from the opposite side. The cells of the somitic scleroderm then undergo resegmentation. This process involves the fusion of the caudal half of a proximal sclerotome with the cephalic half of the next sclerotome. Mesenchymal cells located between the cephalic and caudal portions of the sclerotomes help to form the intervertebral disc. The notochord located in the vertebral bodies disappears, but in the intervertebral disc, it forms the nucleus pulposus.

Thinking of the intervertebral disc as a jelly doughnut may be helpful. The outer doughnut portion is analogous to the annulus fibrosus. The jelly center can be considered analogous to the nucleus pulposus. The literature suggests that in the adult, the notochord does not contribute to the nucleus pulposus.[5]

The Role of Type II Collagen

The embryonic progenitor cells that are positive for type II collagen are critical for the development of the vertebral column and intervertebral disc. Type II collagen-positive cells in long bone include osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and stromal cells. Mice genetically manipulated to lack type II collagen-positive cells during embryogenesis were found dead at birth. At necropsy, the mice were found to lack the vertebral column and intervertebral discs.[6] Mesenchymal stem cells form progenitor cells which can create one to three types of differentiated cells. Progenitor cells that are positive for type II collagen are critical for the development of the vertebral column and the regeneration and repair of the intervertebral disc.[6]

The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Development of the Skeletal System

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent in that they can form a variety of progenitor cells and then differentiate into cells belonging to the bone, cartilage, muscle, and fat cell lineages. Skeletal stem cells reside in multiple sites, including the perichondrium of fetal bone, the perichondrium of adult bone, and bone marrow.[7] MSCs are currently used to repair articular cartilage and intervertebral discs.[8][9] Another critical characteristic of MSCs is that they can form new MSCs, thus maintaining the pool of stem cells belonging to the mesenchymal lineage. The current concept is that multiple types of stem and progenitor cells cooperate in forming, developing, and maintaining cells belonging to the osteogenic and other lineages associated with the vertebral column.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arteries

The neck contains blood vessels that supply blood to structures in the neck and pass through the neck to supply blood to the brain and face. The common carotid and vertebral arteries are the major arteries in the neck.

The left and right common carotid and vertebral arteries run on each side of the neck. Each common carotid artery branches into two divisions: the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid arteries supply blood to the anterior brain via the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, while the external carotid arteries supply blood to the face and neck.

Vertebral arteries also pass through the transverse foramen of the cervical spines before merging to form the basilar artery. Vertebral and basilar arteries supply blood to the posterior brain. The basilar artery anastomoses with the internal carotid arteries, and together they form the circle of Willis, which provides blood to the brain. Vertebral arteries also branch off to give one anterior spinal artery and two posterior spinal arteries. These arteries supply the anterior and the posterior portion of the spinal cord, respectively. Numerous smaller arteries throughout the neck, head, and face branch off from the common carotid and vertebral arteries.[10]

Veins

The major veins in the neck include jugular veins and vertebral veins. The jugular veins diverge to form the external and internal jugular veins. The external jugular vein is more superficial than the internal jugular vein, located in the carotid sheath with the common carotid artery. The external jugular vein collects blood from the superficial skull and the deeper parts of the face. Blood then drains to the subclavian vein. Blood from the brain, the superficial face, and the superficial neck drains into the internal jugular vein. It then merges into the subclavian vein.[10] The vertebral veins drain blood into the subclavian vein after running through the foramen transversarium.

Lymphatics

The lymphatics from the right and left sides of the head and neck drain into the right lymphatic duct and thoracic duct, respectively.

Nerves

The neck muscles are innervated by various cervical nerves and their branches and cranial nerves. Efferent nerves carry impulses from the spinal cord that cause muscles to contract, controlling cervical movements. Sensation to the anterior areas of the neck originates from cervical nerves C2-C4 and the posterior regions of the neck from cervical roots C4-C5. The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius receive innervation by cranial nerve XI (spinal accessory nerve).

The cervical ganglia are a trio of sympathetic nervous system ganglia that lie alongside the vertebral column. The superior cervical ganglion lies at the C2-C3 intervertebral level, while the middle cervical ganglion lies at the C6-C7 intervertebral level. The interior cervical ganglion is fused with the first thoracic ganglion to create the stellate ganglion at the C7-T1 intervertebral level.

The brachial plexus forms from the anterior rami of C5-T1 nerves and divides into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches. After the roots exit the interscalene triangle between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, they form trunks at the level of the subclavian artery. The C5 and C6 roots form the upper trunk, while the C8 and T1 roots form the lower trunk. The C7 root forms the middle trunk. As these trunks cross the clavicle and exit the neck region, they separate into anterior and posterior divisions.

The anterior rami of the C1-C4 vertebrae constitute the cervical plexus. This plexus is posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and anterior to the middle scalene muscle, supplying both muscular and sensory innervation. The cervical plexus provides sensory innervation to the neck, clavicle, and skin surrounding the ear. The muscular branches innervate the infrahyoid muscles, excluding the thyrohyoid muscle and the diaphragm through the phrenic nerve. The phrenic nerve arises mainly from the C4 ventral rami, with smaller contributions from the C3 and C5 rami. The phrenic nerve innervates the diaphragm.

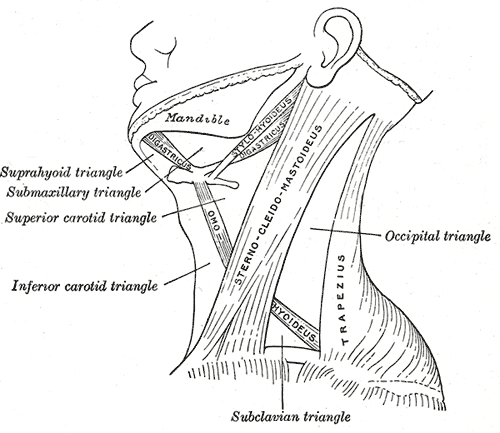

The ansa cervicalis, a part of the cervical plexus, is embedded in the carotid sheath anterior to the internal jugular vein in the carotid triangle. The ansa cervicalis consists of superior and inferior roots. The superior root forms from C1 nerve fibers of the cervical plexus, which travel in the cranial nerve XII and then separate in the carotid triangle to form the superior root. The superior root eventually passes around the occipital artery and then falls on the carotid sheath. The inferior root consists of fibers from spinal nerves C2 and C3. It gives off branches to the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle and the lower parts of the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles. The paralysis of ansa cervicalis may lead to a change in voice quality, probably due to loss of support of infrahyoid muscles to the larynx.

Muscles

The neck muscles can be largely sub-categorized into anterior, lateral (prevertebral), and posterior neck muscles. Listed below are the sub-categories and the action of each muscle in neck movement.

Anterior Neck Muscles

Superficial Muscles

- Platysma: depression of mandible and angle of the mouth, the tension of skin of the lower face and anterior neck

- Sternocleidomastoid: head and neck extension at the atlanto-occipital joint and superior cervical spine; neck flexion at the inferior cervical vertebrae; elevation of the clavicle and sternal manubrium at the sternoclavicular joint; ipsilateral flexion and contralateral rotation of the neck at the cervical spine

- Subclavius: anchoring and depression of the clavicle at the sternoclavicular joint

Suprahyoid Muscles

- Digastric: depression of the mandible, elevation of the hyoid bone during swallowing and speaking

- Mylohyoid: the muscular floor of the oral cavity, elevation of the hyoid bone and floor of the mouth, depression of the mandible

- Geniohyoid: elevation and drawing of hyoid bone anteriorly

- Stylohyoid: elevation and drawing of hyoid bone posteriorly

Infrahyoid Muscles

- Sternohyoid: depression of the larynx

- Sternothyroid: depression of the larynx

- Thyrohyoid: depression of hyoid bone, elevation of the larynx

- Omohyoid: depression of the hyoid bone

Scalene Muscles

- Anterior: neck flexion, lateral flexion of the neck (ipsilateral), neck rotation (contralateral), elevation of the first rib

- Middle: lateral flexion of the neck, elevation of the second rib

- Posterior: lateral flexion of the neck, elevation of the second rib

Lateral Neck Muscles

- Rectus capitis anterior: head flexion at the atlanto-occipital join

- Rectus capitis lateralis: lateral head flexion (ipsilateral) at the atlanto-occipital joint

- Longus capitis: head flexion by bilateral contraction, ipsilateral head rotation by unilateral contraction

- Longus colli: neck flexion and lateral neck flexion (ipsilateral) by bilateral contraction, contralateral rotation of the neck by unilateral neck contraction

Posterior Neck Muscles

Superficial Muscles

- Splenius capitis: extension of head and neck by bilateral contraction, ipsilateral lateral flexion and rotation of the head by unilateral contraction

- Splenius cervicis: extension of the neck by bilateral contraction, ipsilateral lateral flexion and rotation of the neck by unilateral contraction

Suboccipital Muscles

- Rectus capitis posterior major, rectus capitis posterior minor, obliquus capitis superior, and obliquus capitis inferior: all result in the same action - head extension at the atlanto-occipital joint by bilateral contraction, ipsilateral head rotation at the atlantoaxial joint by unilateral contraction

Transversospinalis Muscles

- Semispinalis capitis and cervicis: extension of the head, cervical, and thoracic spine by bilateral contraction; ipsilateral lateral flexion of the head, cervical, and thoracic spine by unilateral contraction; contralateral rotation of the head, cervical, and thoracic spine by unilateral contraction

- Rotatores cervicis: extension of the spine by bilateral contraction, lateral flexion of the spine by unilateral contraction

- Interspinales: extension of the cervical and lumbar spine

- Intertransversarii: assisting in lateral flexion of the spine, stabilization of the spine

Physiologic Variants

Cervical dystonia, or spasmodic torticollis, is a condition due to an abnormal sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle contracture. This condition causes a rotational deformity away from the affected side with a head tilt toward the affected side. It may result from an intrauterine compartment syndrome of the SCM muscle. Clinicians may use passive stretching, botox injections, and possible surgical bipolar release of the sternocleidomastoid or Z plastic lengthening to treat this condition.[11][12] Untreated torticollis may lead to permanent rotational deformity, positional plagiocephaly, facial asymmetry, and dysplasia of the skull, atlas, and axis.

Surgical Considerations

A platysmaplasty, more commonly known as neck lift surgery, is a procedure that tightens the skin and underlying muscles to lift the neck. It also serves to improve and sharpen the contour of the jawline.

Clinical Significance

Cervical Spine Injury

A cervical spine injury must be considered in every trauma patient until further evaluation proves otherwise. Concern for cervical spine injury increases with a history of high-energy trauma, including a motor vehicle accident at more than 35 mph, a fall from more than 10 feet, closed head injuries, and associated fractures of the pelvis or extremities. Common mechanisms of cervical spine injury involve an older person who falls and hits the forehead and a person who is rear-ended and has a whiplash-like injury. When cervical spine injury is suspected, a cervical collar should be placed for stabilization until the presence of a cervical spine injury can be ruled out. Confirmation of the absence of a cervical spine injury can be performed with a physical examination or radiographically (usually with a lateral c-spine view and CT of the head and neck).[13]

"Whiplash" describes a neck injury due to a forceful bending of the neck forward and then backward, or vice versa, past the normal anatomical limits. The injury can involve muscles, vertebral discs, nerves, ligaments, and neck tendons. Most whiplash injuries involve a sudden acceleration or deceleration in a motor vehicle collision. They also commonly occur in contact sports. The ligaments typically affected are the anterior longitudinal ligament, posterior longitudinal ligament, and ligamentum flavum.[14]

Common symptoms of whiplash injury include neck pain and stiffness, dizziness, shoulder and low back pain, tinnitus, blurred vision, concentration problems, irritability, and fatigue. These symptoms can mimic other medical conditions, such as concussions. Diagnosis is possible with a complete medical history, physical examination, and radiographical imaging (i.e., X-ray, MRI, CT scan). The required treatment is determined on a case-to-case basis but may include a cervical collar, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, and surgery if there is structural damage.[15]

The suboccipital triangle forms from a group of muscles located at the base of the skull (rectus capitis posterior major and minor, and the obliquus capitis superior and inferior). A myodural bridge exists between the rectus capitus posterior minor muscle and the intracranial dura. A cervicogenic headache can result when this bridge is stretched or inflamed from cervical spine joint dysfunction or excessive tightness of the suboccipital triangle muscles. Spinal manipulation, soft tissue intervention, and therapeutic exercise may help treat and prevent the future occurrence of a myodural bridge, which will cause headaches.[16]

Chronic degenerative changes of the cervical vertebrae and the intervertebral discs can lead to the narrowing of the intervertebral foramina, potentially leading to the compression of the blood vessels and nerves of the neck, causing cervical radiculopathy.[17]

Hyperextension of the neck could also result in a fracture of the axis (C2), a hangman fracture. The name derives from the fact that this fracture often occurs in people who hang themselves. However, it can also occur due to traumatic injuries. In a sudden, extreme neck hyperextension, the axis bears most of the force, often resulting in a fracture that completely dissociates the anterior and posterior aspects of the axis. The axis is critical in the structural support of the skull and spinal cord. Without an intact axis, spinal cord damage leading to paralysis of the respiratory muscles can occur. Most cases are fatal.[18][19]

Herniation of the Nucleus Pulposus

The nucleus pulposus can herniate through the annulus fibrosus and compress the adjacent nerve root. There are eight cervical nerves and seven cervical vertebrae. Nerve C1 passes above the C1 vertebra. Inferior to C1, the nucleus compresses the nerve one segment lower than the vertebra. Thus, the disc at C8-T1 will compress the T1 nerve root.

The nerve roots at C8 and T1 are the most commonly injured in the cervical segments. Such lesions can involve the brachial plexus. Compression of the T1 nerve root damages the medial cord of the brachial plexus, which contributes to the ulnar nerve and forms part of the median nerve. Thus, damage to the T1 nerve root will cause extreme damage to the intrinsic muscles of the hand due to damage to the ulnar and median nerves.

These are examples of compression injuries, resulting in a compromised blood supply to the affected nerve. The result of such injury is often paresthesia, a condition in which the fine touch sensation is compromised or lost, but the pain and temperature sensation is normal. The pain sensation may be increased (hyperalgesia) because the axons supplying pain are damaged and, therefore, irritable. This dichotomy occurs because the fine-touch fibers are the largest and have the highest oxygen demand. The fibers for pain and temperature are much smaller and can survive when the fine-touch fibers are damaged or dead. However, the pain and temperature fibers can be damaged, producing severe chronic pain.

Compression injuries can compromise motor function, producing a lower motor neuron syndrome. Weakness can result, and atrophy will occur in more severe cases in the muscles innervated by a ventral root of the mixed spinal nerve.