Issues of Concern

The Anterior Pituitary (Adenohypophysis)

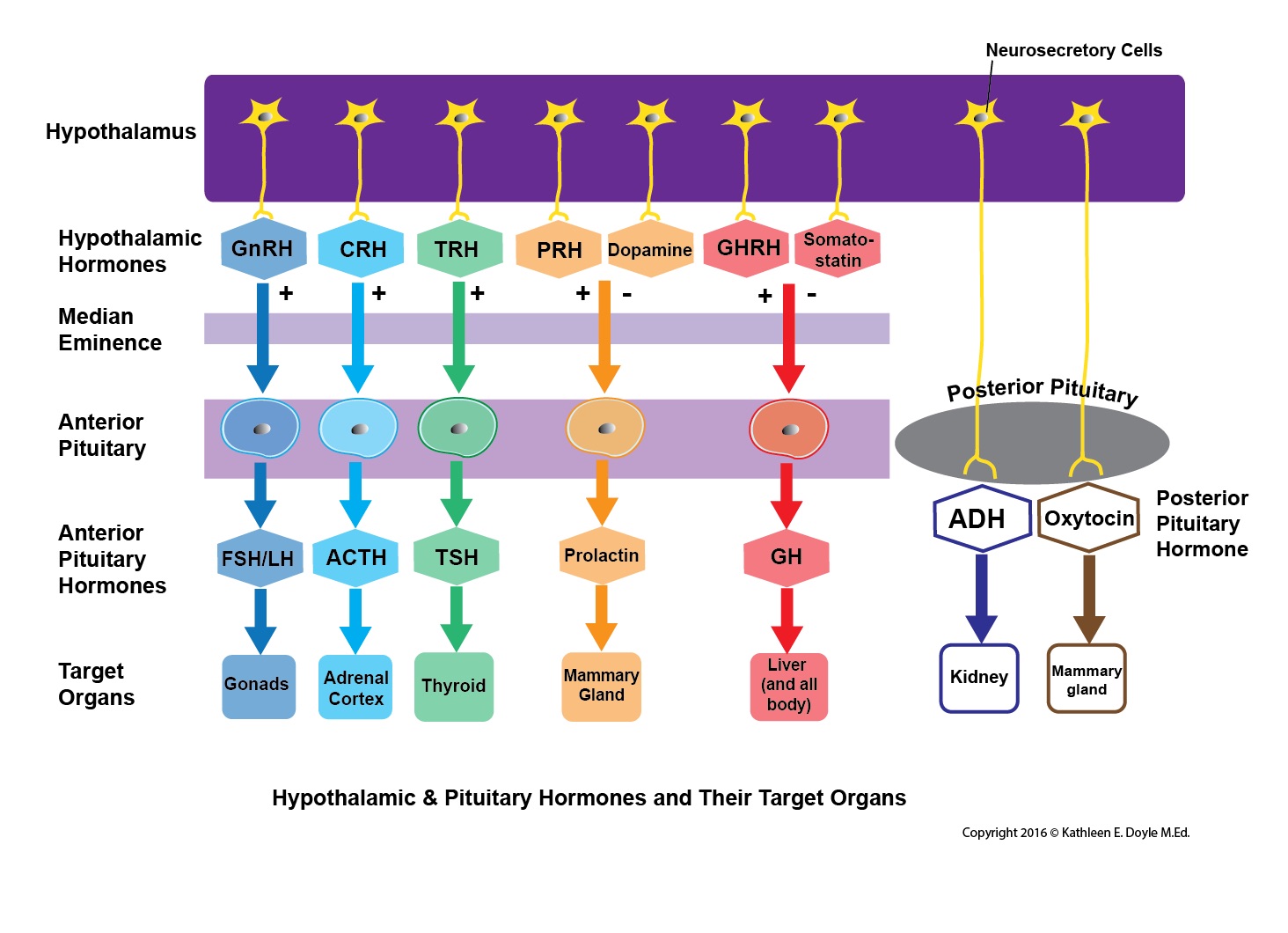

The anterior pituitary is derived from embryonic ectoderm. It secretes five endocrine hormones from five different types of epithelial endocrine cells. The release of anterior pituitary hormones is regulated by hypothalamic hormones (releasing or inhibitory), which are synthesized in the cell bodies of neurons located in several nuclei that surround the third ventricle. These include the arcuate, the paraventricular and ventromedial nuclei and the medial preoptic and paraventricular regions. In response to neural activity, the hypothalamic hormones are released from the nerve endings into the hypophyseal portal blood and are then carried down to the anterior pituitary.[5][6][7]

Anterior Pituitary (AP) Hormones

Growth hormone (GH)

Other names: somatotropic hormone or somatotropin

Precursor cells: somatotrophs in the AP

Target cells: almost all tissues of the body

Transport: 60% circulates free and 40% bound to specific GH-binding proteins (GHBPs)

Mechanism of action:

GH binds to growth hormone receptors (GHRs) causing dimerization of GHR, activation of the GHR-associated JAK2 tyrosine kinase, and tyrosyl phosphorylation of both JAK2 and GHR. This causes recruitment and/or activation of a variety of signaling molecules, including MAP kinases, insulin receptor substrates, phosphatidylinositol 3' phosphate kinase, diacylglycerol, protein kinase C, intracellular calcium, and Stat transcription factors. These signaling molecules contribute to GH-induced changes in enzymatic activity, transport function, and gene expression that ultimately culminate in changes to growth and metabolism.

Regulation of GH secretion:

The release of GH is under dual control by the hypothalamus. GH secretion is stimulated by growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) but suppressed by another hormone peptide, somatostatin (also known as growth hormone-inhibiting hormone (GHIH)). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) provides negative feedback for inhibiting GH release from somatotrophs. Thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) up-regulate GH gene expression in somatotrophs.

Physiological Functions:

GH acts almost on every type of cell. Its principal targets are bones and skeletal muscles. It has direct metabolic effects on fats, proteins, and carbohydrates and indirect actions that result in skeletal growth.

- Direct Metabolic Functions: GH is anabolic. It stimulates the growth of almost all tissues of the body that are capable of growing (increase in the number of cells). GH also increases the rate of protein synthesis in most cells of the body and decreases the rate of glucose utilization throughout the body (diabetogenic action). Also, it increases the mobilization of fatty acids from adipose tissue and increases levels of free fatty acids in the blood.

- Indirect Actions on Skeletal Growth: GH stimulates the production of IGF-1 from hepatocytes. IGF-1 mediates the growth-promoting effects of GH on the skeleton. IGF-1 exerts direct actions on both cartilage and bone to stimulate growth and differentiation. These effects are crucial for growth during childhood to the end of adolescence.

Prolactin[8]

Precursor cells: mainly from lactotrophs in the AP

Target cells: main target cells are mammary glands and gonads

Mechanism of action: binds to peptide hormone receptor (single transmembrane domain) to activate the JAK2-STAT intracellular signaling pathway similar to that of GH

Regulation: Like GH, dual hypothalamic inhibitory (from dopamine) and stimulatory hormones (PRH) regulate prolactin secretion. The predominant hypothalamic influence is inhibitory.

Physiological Functions: The main functions of prolactin are stimulating mammary gland growth and development (mammographic effect) and milk production (lactogenic effect). It also has effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and can inhibit pulsatile GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)

Precursor cells: gonadotrophs in the AP

Target cells: gonads (ovaries and testes)

Mechanism of action: FSH and LH bind to G protein-coupled receptors to activate adenylyl cyclase enzyme, which in turn increases intracellular cAMP. cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) that phosphorylates intracellular proteins. These phosphorylated proteins then accomplish the final physiologic actions.

Regulation: FSH and LH secretion are under the control of the hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH).

Physiological Functions: FSH and LH regulate the functions of the ovaries and the testes. In females, FSH stimulates growth and development of follicles in preparation for ovulation and secretion of estrogens by the mature Graafian follicle. LH triggers ovulation and stimulates the secretion of progesterone by the corpus luteum. In males, FSH is required for spermatogenesis, and LH stimulates testosterone secretion by Leydig cells.

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)[9]

Precursor cells: thyrotropes in the AP

Target cells: thyroid follicular cells

Mechanism of action: TSH binds to the G-protein-coupled receptors on the basolateral membrane of the thyroid follicular cells. Similar to FSH and LH, it activates the adenylyl cyclase-PKA-cAMP system to phosphorylate several proteins, which in turn achieve the final physiologic actions

Regulation: TSH secretion is under the control of the hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). Also, T4 feeds back to the anterior pituitary to inhibit TSH secretion.

Physiological functions: the main function of TSH is to stimulate synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormones (tri-iodothyronine [T3] and thyroxine [T4]) from thyroid follicles. It also maintains the structural integrity of the thyroid glands.

Adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)

Precursor cells: corticotrophs in the AP

Target cells: cells in the cortex of the adrenal glands (adrenocortical cells)

Mechanism of Action: ACTH binds to its G-protein coupled receptors on the adrenocortical cells. Similar to TSH, FSH, and LH, it activates adenylyl cyclase-PKA-cAMP system to phosphorylate several proteins, which in turn achieve the final physiologic functions.

Regulation: ACTH secretion is under the control of the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). It is subject to negative feedback regulation.

Physiological functions: the main function of ACTH is to stimulate the secretion of adrenal cortex hormones (mainly glucocorticoids) during stress.

The Posterior Pituitary (Neurohypophysis)[10]

The posterior pituitary is neural in origin. Unlike the anterior pituitary, the posterior pituitary is connected directly to the hypothalamus via a nerve tract (hypothalamohypophyseal nerve tract). It secretes two hormones: oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) or vasopressin. The hormones are synthesized by the magnocellular neurons located in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus. The hormones are transported in association with neurophysins proteins along the axons of these neurons to end in nerve terminals within the posterior pituitary.[3]

Oxytocin

Precursor cells: paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei in the hypothalamus

Target cells: myoepithelial cells of the mammary glands and the uterine muscles (myometrium) in women and myofibroblast cells in the seminiferous tubules in men.

Mechanism of action: oxytocin acts on its target cells via a G-protein coupled receptor, which activates phospholipase C that in turn stimulates phosphoinositide turnover. This causes increased intracellular calcium concentration, which activates the contractile machinery of the cell.

Regulation: oxytocin is released in response to an afferent neural input to the hypothalamic neurons that synthesize the hormone. Suckling and uterine stimulation by the baby’s head during delivery are the major stimuli for oxytocin release. It is subject to positive feedback regulation.

Physiological Functions: oxytocin stimulates milk ejection from the breast in response to suckling (milk ejection reflex). It causes contraction of myoepithelial cells surrounding the ducts and alveoli of the gland and therefore milk ejection. Oxytocin also stimulates uterine contraction during labor to expel the fetus and placenta.

Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH) or Vasopressin

Precursor cells: paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus.

Target cells: renal distal convoluted tubules and collecting duct and vascular smooth muscle cells.

Mechanism of action: similar to oxytocin, it acts on its target cells via a G-protein coupled receptor, which activates phospholipase C that in turn stimulates phosphoinositide turnover and causes an increase in intracellular calcium concentration which in turn achieves the final physiologic actions.

Regulation: The main stimulus for ADH release is an increase in osmolality of circulating blood. Osmoreceptors located in the hypothalamus detect this increase and activate the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei to release ADH. It also releases in response to hypovolemia.

Physiological Functions: ADH binds to V2 receptors on the distal tubule and collecting ducts of the kidney to up-regulate aquaporin channel expression on the basolateral membrane and increase water reabsorption. It, as its name suggests, also acts as a vasoconstrictor upon binding to V1 receptors on the arteriolar smooth muscle.

Clinical Significance

Hyperprolactinemia[11]

Abnormally elevated levels of prolactin in the blood.

Causes: Most commonly, it is caused by a prolactin-secreting adenoma (prolactinoma). Other causes include medications, pregnancy, lactation, stress, and cranial radiation therapy.

Pathophysiology: the excess prolactin causes gonadal dysfunction, which occurs in 90% of women with prolactinomas. The excess prolactin inhibits the normal secretion of LH and FSH and the midcycle LH surge, leading to a lack of ovulation.

Acromegaly and Gigantism

Excess of GH after epiphyseal closure causes acromegaly whereas gigantism results from GH hypersecretion before epiphyseal closure. Acromegaly occurs more frequently than gigantism.

Causes: pituitary adenomas composed of somatotrophs.

Pathophysiology: excess GH causes an increase in the growth of soft tissues and increases in IGF-1production from the liver, which promotes growth in the bones of the hands and feet. Individuals with acromegaly may also develop carbohydrate intolerance and diabetes due to excess GH.