Continuing Education Activity

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a common cause of chest pain that causes significant morbidity and mortality. Posterior wall myocardial infarction occurs when circulation becomes disrupted to the posterior heart. It commonly cooccurs with inferior or inferolateral MI, but when in isolation, posterior myocardial infarction represents a diagnostic challenge. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of posterior myocardial infarction and highlights the role of the interprofessional healthcare team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify when to suspect and how to diagnose posterior myocardial infarction accurately.

Describe the EKG findings associated with posterior myocardial infarction.

Summarize the treatment and management options available for posterior myocardial infarction.

Identify the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients affected by posterior myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a common cause of chest pain that causes significant morbidity and mortality. Posterior wall myocardial infarction occurs when circulation becomes disrupted to the posterior heart. It commonly cooccurs with inferior or inferolateral MI, but when in isolation, posterior myocardial infarction represents a diagnostic challenge. Patients may present with classic symptoms of myocardial infarction, but due to more subtle EKG changes, it is a diagnosis that is often missed or misdiagnosed. Rapid recognition of this condition is essential to adequately treat it and reduce the risk of complications, including death.

Etiology

The reduction of coronary blood flow causes myocardial infarction. Classically this occurs due to atherosclerotic plaque rupture or intraluminal thrombus and is referred to as type I myocardial infarction. However, ischemia may also occur due to either increased oxygen demand or decreased supply and is called type II myocardial infarction; this may be triggered by many conditions such as hypertension, hypotension, coronary artery spasm, anemia, sepsis, and arrhythmias.

Posterior myocardial infarction occurs when the posterior coronary circulation becomes disrupted. The two main branches of the coronary circulation are the right coronary artery and the left main coronary artery. The left main coronary artery is a short, wide caliber vessel that divides into the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the left circumflex artery (LCx). On occasion, there may be a small branch called the ramus intermedius, which comes off the angle between the LAD and LCx. In approximately 70% of the population, the right coronary artery (RCA) supplies the posterior descending artery (PDA), which supplies the posterior circulation. This arrangement is known as "right dominant" circulation. In about 10% of the population, the posterior descending artery originates from the LCx artery, known as "left dominant" circulation. In the remaining 20% of the population, the RCA and LCx both supply the posterior descending artery, known as co-dominant circulation. Occlusion of the vasculature will lead to ischemia in the territory supplied, but the patient's anatomy determines what provides the posterior circulation.

There are a number of risk factors for coronary artery disease and, by extension, myocardial infarction. The HEART score is a diagnostic pathway used in patients older than 21 years of age who present with symptoms suggestive of ACS. It is used to stratify risk and is predictive of the 6-week risk of a major adverse cardiac event. It is not for use in patients with ST-elevation or other new EKG changes, hypotension, or other comorbid conditions requiring admission, but the risk factors apply to any patient in whom there is a concern for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Risk factors considered as a component of the HEART score include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity (BMI over 30 kg/m^2), smoking (current or smoking cessation three months), positive family history (parent or sibling with coronary vascular disease [CVD] before age 65); atherosclerotic disease: prior MI, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), or peripheral arterial disease.[1]

Epidemiology

Posterior myocardial infarction reportedly represents 15% to 21% of acute MI. It is frequently associated with inferior and/or lateral MI, which can lead to a significant area of infarction. The incidence of isolated posterior MI has been reported at about 3.3% using posterior leads, though this may still be an underestimate as posterior leads are not routinely employed.[2]

Also, certain factors correlate with delayed presentation of ACS. These include female sex, older age, Black or Hispanic race, low educational status, and low socioeconomic status. Women are less likely to receive treatment with guideline-directed medical therapies and undergo cardiac catheterization. While men are more likely to report central chest pain, women can present with more atypical symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, indigestion, nausea or vomiting, palpitations, or weakness.[3]

Pathophysiology

Myocardial infarction results from decreased blood flow to myocardial tissue. The most common type of myocardial infarction, type 1 MI, is due to the rupture of a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque comprising of macrophages, smooth muscle proliferation, and lipid-laden foamy cells that form on an injured vascular wall. When there is complete or near-complete occlusion of the vessel, there is little to no perfusion of the affected myocardium. This perturbed blood flow leads to ischemia, which has downstream effects of metabolic and ionic disturbances in the myocardium. Prolonged ischemia leads to apoptosis and necrosis of cardiomyocytes and cell death. Healing occurs through scar formation and is dependent upon an inflammatory cascade, which is triggered by the release of cytokines from dying cells — infiltrating phagocytes clear dead cells and matrix debris. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is activated. Transforming growth factor-beta is released and triggers the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins. The subsequent remodeling ultimately leads to dilation, scar formation, and progressive dysfunction.[2][4]

History and Physical

Chest pain is a common complaint encountered in the emergency department, and it is essential to keep a broad differential in mind. The top six differentials of chest pain need to be immediately ruled out, given their life-threatening consequences. These are acute myocardial infarction, pericardial tamponade, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, and esophageal rupture. In the acute setting, most patients who present with chest pain will have an EKG performed immediately. The EKG may have changes that are concerning for ischemia, but it is important to remember: do not only treat the EKG. First, compare it to a prior EKG. Also, missing another diagnosis, like aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism, can delay appropriate care and result in inappropriate interventions, which may be life-threatening.

History

A thorough history, including onset, duration, provoking, and relieving factors, quality, and associated factors is critical. Posterior myocardial infarction, like other types of myocardial infarction, classically presents with chest pain. Patients often describe the pain as crushing substernal chest pain or pressure. Many patients insist it is only pressure and will not describe it as pain or use phrases like "an elephant sitting on my chest." They may have radiation to the arms, jaw, or epigastrium. The sensation may be relieved with nitroglycerin.

While not a definitive way to differentiate chest pain of cardiac origin from chest pain from other causes, there are factors that increase and others that decrease the likelihood of ACS.

Factors that increase the probability of ACS include:

- associated with nausea or vomiting

- associated with diaphoresis

- is worse with exertion or strong emotion

- Chest pain that radiates to the arms or jaw

Factors that decrease the probability of ACS include:

- pleuritic in nature

- positional

- is described as sharp or stabbing and less than 1 minute

- Reproducible chest pain

In patients with these symptoms, it is essential to remember that MI is less likely, but by no means excluded. However, if the latter factors are present, additional history should be obtained, including risk factors for pulmonary embolism (PE). These are a history of unilateral leg swelling, recent surgery or trauma, history of PE or deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the past, hormone use, recent immobilization, history of malignancy, or hemoptysis. Chest pain that began after an inciting injury or strain may be musculoskeletal. Abdominal causes of chest pain include gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), cholecystitis, and peptic ulcers.

Exam

The presentation of myocardial infarction is variable. The patient may present fairly well-appearing or might be obviously in extremis. In every patient with chest pain, it is important to perform a focused physical exam.

- Obtain vital signs, including blood pressures in both arms.

- Heart rate

- Tachycardia is common, but bradycardia with or without heart block may ensue if the RCA is involved as it typically supplies the SA and AV nodes

- Arrhythmia is possible at any time in the course of myocardial infarction

- Blood pressure

- Hypertension is common and may be significant, but hypotension is possible and raises mortality risk.

- Isolated posterior infarction is less common than posterior infarct associated with inferior/inferolateral infarction. As such, the infarcted area may be preload dependent, and the administration of nitroglycerin may lead to significant hypotension.

- A significant discrepancy between blood pressure in each arm should raise concern for aortic dissection.

- General appearance

- Patients may be ill-appearing, diaphoretic, or in obvious distress.

- Levine's sign: holding a clenched fist to the chest

- Neck

- Look for jugular venous distention, a sign of heart failure.

- Heart exam

- Murmurs

- Acute mitral regurgitation due to ischemia of the papillary muscles may be silent or produce a murmur. The regurgitation is better appreciated by echocardiography with Doppler.

- Concomitant aortic stenosis may result in significant hypotension if the patient receives nitroglycerin.

- Distant heart sounds may be a result of pericardial effusion, which should raise suspicion of other etiologies like dissection and subsequent hemopericardium.

- Lung exam

- Bilateral rales on auscultation are likely secondary to heart failure

- Unequal breath sounds should raise concern for pneumothorax

- Chest exam

- Tenderness to palpation of the chest wall may be musculoskeletal

- "Hamman's crunch" or Crepitus is evidence of subcutaneous emphysema, which may be from rib fractures, pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum

- Abdominal exam

- Tenderness in the abdomen should prompt concern for intra-abdominal etiology (cholecystitis, pancreatitis, GERD), which may lead to radiation of pain into the chest or difficulty differentiating visceral abdominal pain from chest pain.

- Neurological exam

- Neurologic deficits should also raise the suspicion for aortic dissection

- Extremities

- Edema: bilateral edema can be evidence of heart failure whereas unilateral edema should prompt further evaluation for DVT and PE

- Pulse deficits, mottling, or cool extremities are evidence of decreased perfusion. If unilateral, consider aortic dissection

- Patients may present in cardiac arrest. If the presenting rhythm is ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia, the recommendation that the patient goes for coronary angiography after achieving the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and the patient is stable for transfer.

Evaluation

For any patient presenting with chest pain concerning ACS, cardiac workup should be initiated, including history and exam as above, electrocardiogram (EKG), and cardiac biomarkers.

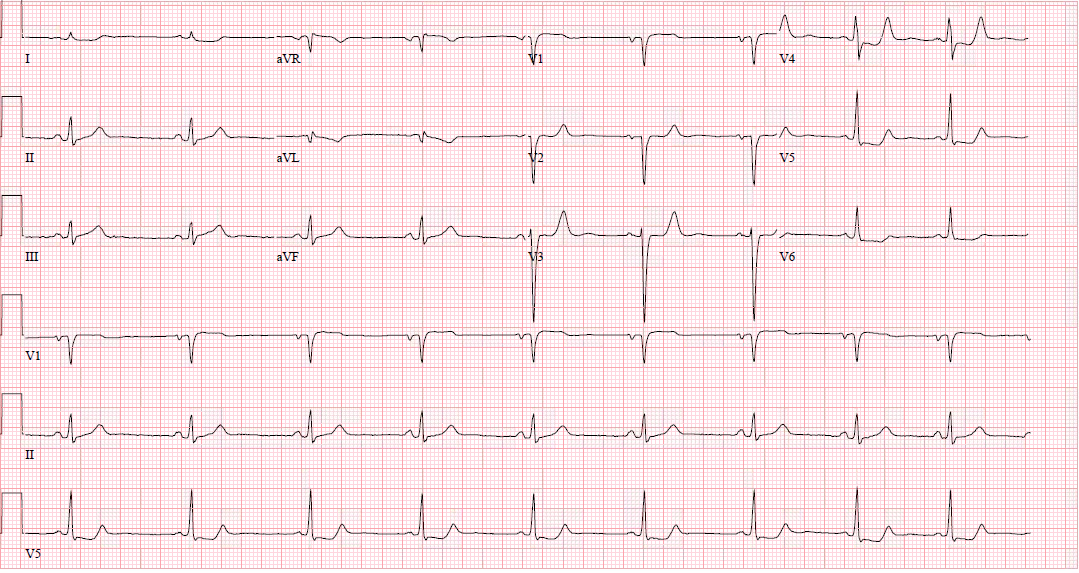

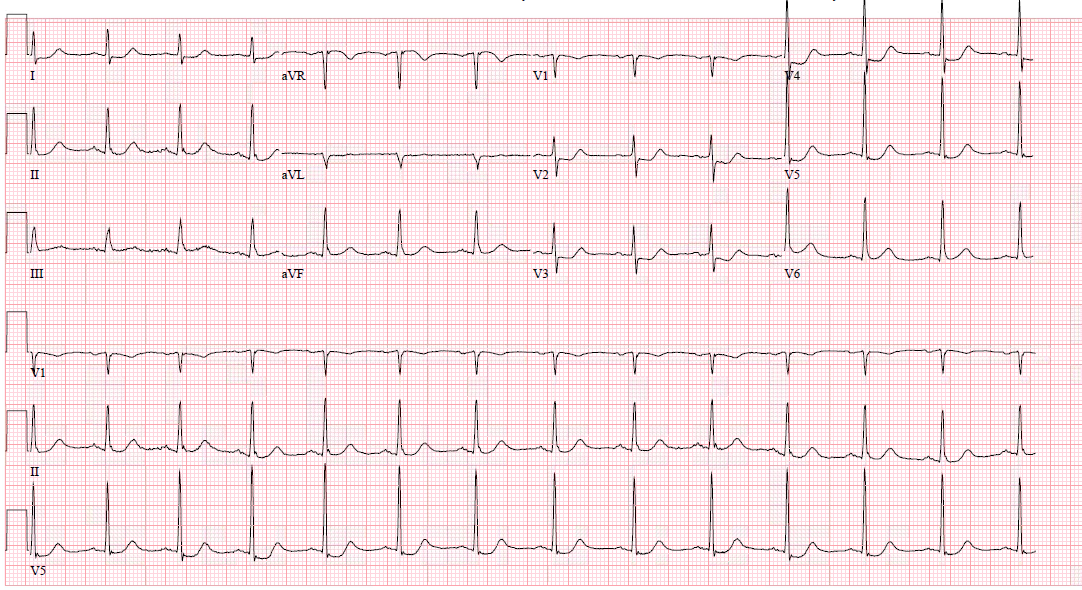

EKG

In a typical 12-lead EKG, posterior infarction is an indirect observation due to the placement of the leads.

Limb leads placement is on each of the four extremities.

Precordial leads are placed on the anterior chest

- V1 - 4th intercostal space on the right margin of the sternum

- V2 - 4th intercostal space on the left margin of the sternum

- V4 - 5th intercostal space at the midclavicular line

- V3 - midway between V2 and V4

- V5 - 5th intercostal space on the anterior axillary line at the level of V4

- V6 - 5th intercostal space on the midaxillary line at the level of V4

Areas of infarction

- Inferior - II, III, aVF (RCA or LCx)

- Lateral - I, aVL, V5, V6 (LCx or diagonal branch of LAD)

- Septal - V1, V2 (LAD)

- Anterior - V2, V3, V4 (LAD)

ST-elevation is visible if there is inferior, lateral, or inferolateral involvement associated with a posterior extension. However, ST-elevation will not show on the typical EKG in isolated posterior MI, and other EKG changes may be observable. However, for further clarification, posterior leads (V7-V9) may be placed to evaluate further. [5][6][5]

Posterior leads V7-V9 get placed on the posterior chest wall in the same horizontal plane as V6

- V7 - left posterior axillary line

- V8- the tip of the left scapula

- V9 - left paraspinal region

ST-elevation may be more subtle, and ST-elevation greater than 0.5 mm in one lead indicates posterior ischemia and is diagnostic for posterior ST-elevation MI (STEMI). When possible, compare to old EKGs.

Other changes that may present in posterior STEMI include:

- ST-depression in the anterior leads, which may be deep (over 2 mm) and flat

- Large R-wave in V2-V3, which are larger than the S-wave

- R-waves in V2-V3 that are greater than those in V4-V6 is an abnormal R-wave progression

- Large and upright anterior T waves

- Signs of ischemia in inferior and/or lateral territories, including possible ST elevation

- Mirror image effect of EKG regarding posterior wall ischemia

- If turned upside down, tall anterior R-waves become deep posterior Q-waves, ST-depression becomes ST-elevation, and upright T-waves become inverted T-waves

- If these changes are not present, it does not rule out posterior STEMI[7][8]

If there is an obvious posterior STEMI, and there is low suspicion of other pathology, the goal is to get the patient the lab for percutaneous intervention (PCI). There is no need to wait for lab results. IV access should be obtained, and labs sent. If there are more subtle EKG changes, but not definitive STEMI, consider serial EKGs. Sometimes on repeat EKGs, subtle ischemia evolves into STEMI.

Lab Studies

- CBC

- Metabolic profile

- Troponin

- Coagulation studies

- Consider B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) / NT pro-BNP

Imaging Studies

- Obtain bedside chest x-ray (CXR) or two-view CXR

- Consider bedside echocardiography; this is an operator-dependent skill but can be of significant value. Bedside echocardiography can evaluate for pericardial effusion, gross wall motion abnormalities, size of the ventricles, valvular abnormalities, and ejection fraction estimation. A suprasternal notch view is useful to visualize the aorta and evaluate for possible dissection. The proximal aorta is usually dilated with or without a visible intimal flap.

Treatment / Management

Reperfusion

The definitive management of acute posterior STEMI is reperfusion therapy. Optimally this is done via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), though the next option would be fibrinolytic therapy. PCI is the preferred option if it can be initiated within 120 minutes, though within 90 minutes is the goal. If PCI is not available within 120 minutes, then fibrinolytic therapy should be given within 30 minutes.

Adjunctive Therapies

- Aspirin 162 to 325 mg chewable or 600 mg per rectum

- Aspirin should be given as soon as STEMI is suspected. Aspirin reduced mortality.

- Nitroglycerin (NTG)

- Should be given sublingually for rapid absorption and onset of action. It aides coronary vasodilatation and helps with symptomatic relief of angina. It does not reduce mortality. The most common side effect is a throbbing headache. NTG should not be given in inferior myocardial infarction due to the risk of hypotension. The right ventricle is preload dependent, and the vasodilation decreased blood return. [9]

- It is imperative to ask male patients if they have used phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as sildenafil, vardenafil, or tadalafil, within 24 hours as the combination can cause life-threatening hypotension.

- Oxygen

- To only be used if SpO2 less than 90%. The AVOID trial SHOWED that in patients with STEMI who are not hypoxic, supplemental oxygen therapy might increase early myocardial injury and was associated with larger infarct size at six months.[10]

- Antiplatelet agents

- Clopidogrel: 600 mg loading dose for STEMI or 300 mg for NSTEMI followed by 75 mg daily

- Ticagrelor: 180 mg loading dose followed by 90 mg twice daily

- GPIIB/IIIa inhibitors - not routinely used

- Abciximab, eptifibatide

- These are now much less commonly used since the advent of other agents and stents due to increased risk of bleeding.

- Beta-blockers

- Oral beta-blockers should be initiated within 24 hours.

- ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

- Therapy should start within 24 hours in stable patients.

- Statin

- High-intensity statin therapy should begin as soon as possible.

- Anticoagulation

- Heparin is required after thrombolysis to prevent re-thrombosis. Patients undergoing PCI should undergo heparinization to prevent thrombosis during the procedure

- Other agents like low molecular weight heparin, fondaparinux, and bivalirudin may be alternatives.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for chest pain is broad and should narrow based on history, physical exam, and other diagnostic tests as above.

Critical diagnoses that require emergent management: Colloquially known as "6 deadly causes of chest pain."

- Acute coronary syndromes

- STEMI

- NSTEMI

- Unstable angina

- Aortic dissection

- Pulmonary embolism

- Cardiac tamponade

- Tension pneumothorax

- Esophageal perforation - Boerhaave syndrome

Other diagnoses may still require urgent or emergent management and include:

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Mediastinitis

- Pneumomediastinum

- Pneumothorax

- Hemothorax

- Asthma exacerbation

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Prinzmetal angina

- Drug-induced chest pain (particularly cocaine)

- Cholecystitis

- Pancreatitis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

- Esophageal spasm

- Biliary colic

- Rib fractures

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Herpes zoster

- Psychosomatic chest pain

Prognosis

Due to the more subtle EKG changes in an isolated posterior myocardial infarction, the diagnosis is more likely to be missed than ischemia in other regions. Assuming it is appropriately detected, no data demonstrate a significant difference in mortality when comparing posterior STEMI versus other STEMI. Patients who present with STEMI and undergo PCI within 2 hours have 30-day mortality from 3% to 5%. However, if there is an inferior or lateral myocardial infarction that has extension posteriorly, there is a significant area affected by the infarct. These patients have an increased risk of complications, such as left ventricular dysfunction and death.[11][6][12][5]

Complications

Several complications may result from myocardial infarction. Arrhythmias are possible at any point in the course of MI but are common early in the course, within the first three days. It is possible to develop reinfarction or extension of infarction. Mechanical complications are also possible and may include ventricular free wall rupture, ventricular septal rupture, papillary muscle rupture, acute mitral valve regurgitation, and ventricular aneurysms. These carry significant morbidity and mortality. Heart failure and cardiogenic shock are possible. There is an increased risk of embolic phenomena, which can lead to peripheral ischemia or stroke. Pericarditis, which may be early or late, can also occur. Late-onset pericarditis is also known as Dressler syndrome or post-cardiac injury syndrome and is an autoimmune response.[13]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Cardiac disease has a high risk of morbidity and mortality. Patients require education about their modifiable risk factors and how to control them. Well-established risk factors include tobacco use, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Other independent behavioral risk factors that contribute include obesity, physical inactivity, and sedentary behavior.[14] Patients should also need counsel regarding recognizing symptoms that may be concerning for myocardial infarction, how and when to take nitroglycerin if it has been prescribed, and when to call 911.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Due to the significant morbidity and mortality with which myocardial infarction is associated, prevention and treatment require an interprofessional team. Prevention of cardiac disease in the outpatient setting is of critical importance. This process involves the patient's primary care provider and other outpatient staff, including nurses, pharmacists, and dieticians. In the event of acute myocardial infarction, the first line is often EMS, who are responsible for transporting the patient to the ED, administering medications like aspirin and nitroglycerin, and obtaining an initial EKG. If EKG causes immediate concerns for STEMI, posterior, or otherwise, the cath lab should be activated from the field. EMS may also be responsible for resuscitating patients in cardiac arrest, which may be secondary to STEMI. In the emergency department, physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, nursing staff, and technicians play a critical role in establishing the diagnosis of ACS, initiating resuscitation, and activating further resources. An initial EKG should take place within 10 minutes, and patients should undergo appropriate reperfusion therapy as soon as possible. Cardiologists play a critical role in reperfusion therapy and ongoing stabilization and monitoring of patients who have had a myocardial infarction. Depending on the degree of disease and other common comorbidities or complications, a cardiothoracic surgeon may further play a role in surgical management via coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacements. For these processes, cardiology-specialized nursing can assist with the procedures and provide post-operative care, informing the cardiologist immediately of any concerns in the patient's condition. Patients initially require intensive care, requiring all levels of staff to monitor for life-threatening complications and provide appropriate care. After initial resuscitation, patients may require assistance from dieticians, pharmacy, social workers or case managers, physical therapy, and occupation therapy to transition out of the hospital appropriately. Pharmacists will vet all medications on arrival to the ER, and as well, in the post-operative and rehabilitative setting, verifying dosing, duration, and checking for interactions, and informing the team of any issues. Patients benefit from ongoing cardiac rehabilitation and addressing modifiable risk factors. Education regarding the importance of maintaining healthy body weight, cholesterol, and blood glucose, as well as the cessation of tobacco use and adherence to their prescribed medications, can lead to better outcomes.[15][16] [Level 2] All these functions are best delivered and managed via the interprofessional healthcare team, leading to more robust patient outcomes. [Level 5]