Structure and Function

GROSS ANATOMY OF THE PITUITARY GLAND

The pituitary gland undergoes rapid growth from birth to adult life to reach a weight of 500 mg. The adult gland has an anteroposterior diameter of 8 mm and a transverse diameter of 12 mm. There is a discrepancy between the size of the gland in males and females. During pregnancy, it almost doubles in size as the pars distalis enlarges. Pars distalis is a part of the anterior pituitary. It is bound superiorly by the diaphragma sellae, anteroinferiorly by the sphenoid sinus, and laterally by the cavernous sinus. The optic chiasm lies anterosuperior to the gland. The tuber cinereum and median eminence of the hypothalamus give origin to an infundibulum. The tubular infundibulum connects the hypophysis to the brain. Due to the dual origin of the gland, they have a unique histological appearance. They are made up of anatomically and functionally distinct lobes called the anterior lobe (adenohypophysis), posterior lobe (neurohypophysis), and intermediate lobe.[1][2]

The pituitary gland is within the sella turcica or the hypophyseal fossa. This structure is present near the center at the base of the cranium and is fibro-osseous. The anatomical boundaries of the gland have clinical and surgical significance. Sella turcica is a concave indentation in the sphenoid bone. The reflections of the dura bound the fossa laterally and superiorly.

Sellar Anatomy

The bony walls of the sella turcica surround the fossa in the anterior, posterior, and inferior margins. The pituitary gland, along with the sella turcica, constitutes the sellar region. Tuberculum sellae makes up the anterior wall, and dorsum sellae makes up the posterior bony wall. Anterosuperior to the tuberculum is the sulcus chiasmaticus. The margins of the dorsum sellae form rounded structures called the posterior clinoid process. The anterolateral margin of the sella turcica forms the anterior clinoid process. These two clinoid processes aids in the attachment of the dural folds. The roof of the sphenoid sinus forms the floor of the pituitary fossa. The diaphragma sellae is a dural fold with a central aperture, and it covers the sella turcica as a roof incompletely. The adenohypophysis is separated from the optic chiasm by the diaphragma. It is continuous with the dura. The pituitary stalk and the blood vessels travel via the central aperture.

Parasellar and Suprasellar Anatomy

The cavernous sinus and the suprasellar cistern encompasses the parasellar region. The lateral walls of the pituitary fossa are made up of dura mater, and it contains the cavernous sinus. The cavernous sinus consists of the internal carotid artery, sympathetic fibers, cranial nerves III, IV, V, and VI. The suprasellar cistern encompasses the optic chiasm, part of the third ventricle, hypothalamus, and the tuber cinereum. This tuber cinereum is a gray matter lamina. Researchers identified an increased concentration of type IV collagen in the pituitary gland and surrounding tissue, including the capsule. This tissue has clinical importance as it has implications in the adenoma progression and invasion of adjacent structures.[1][3]

ANTERIOR PITUITARY GLAND

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY

The adenohypophyses constitute well-defined acini, consisting of cells that produce and secrete hormones. There are six cell lines, of which five are hormone-producing cell types called somatotrophs, lactotrophs, corticotrophs, thyrotrophs, and gonadotrophs. Also, a nonhormone producing sixth cell type in the anterior pituitary is called the folliculostellate cells. The anterior pituitary gland encompasses the following structures:

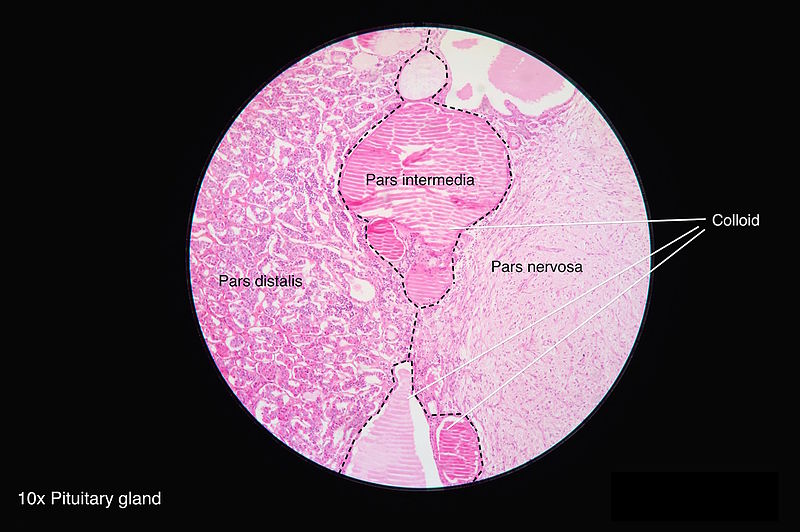

Pars Distalis: This is located at the distal part of the gland, and most of the hormones get secreted from this region. It forms the major bulk of the anterior pituitary. It is composed of follicles of varied sizes. Based on the staining methods used, the hormone-producing cells are classified below:

Acidophils: They are composed of polypeptide hormones, and their cytoplasm stains red to orange in color. The somatotrophs and lactotrophs are the acidophils.

Basophils: They are composed of glycoprotein hormones and their cytoplasm stains blue to purple in color. The thyrotrophs, gonadotrophs, and corticotrophs are the basophils.

Chromophobes: They do not stain well. They may represent stem cells that are yet to differentiate into mature hormone-producing cells.

Pars Tuberalis: The tubular stalk is divided into pars tuberalis anteriorly and posteriorly. It extends from the pars distalis. The pars tuberalis encircles the infundibular stem, which is composed of unmyelinated axons from the hypothalamic nuclei. The hormones oxytocin and vasopressin accumulate in these axons, forming ovoid eosinophilic swellings along the infundibular stem. They make up the ‘herring bodies.’

Pars Intermedia: This is present between the pars distalis and the posterior pituitary gland. It is made up of follicles containing a colloidal matrix and includes the remainder of the Rathke's pouch cleft. Though it is mostly nonfunctioning, they produce melanocyte-stimulating hormones, endorphins and have some pituitary stem cells.

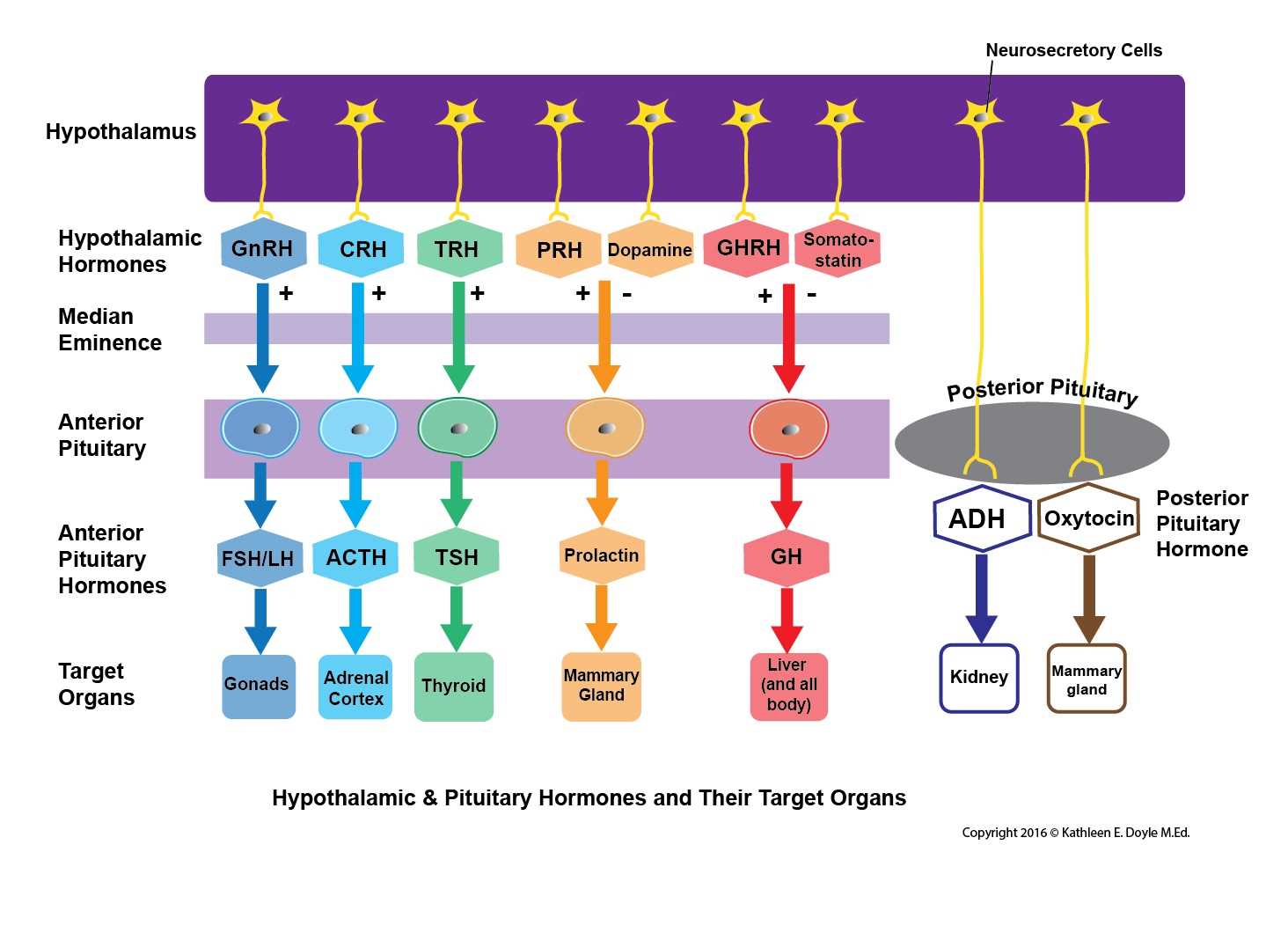

The hypothalamus is where the initial primary signal hormones get synthesized to stimulate the pituitary gland. Their synthesis is in the cell body of the neurons following which the axons project to terminate at the gland in the fenestrated portal capillaries. Then they travel via the bloodstream to the pituitary gland to stimulate the specific cells or inhibit them.

FUNCTION

The following are the hormones produced and secreted from the anterior pituitary.

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH): The release of this hormone from the gland is in response to the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus. The CRH reaches the target location via the portal system and cleaves the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) into three major substances that are the ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, beta-endorphins. They then travel to reach the adrenal cortex, via the bloodstream to facilitate the release of cortisol. The negative feedback from cortisol regulates CRH and ACTH. They aid in the secretion of glucocorticoids during stress.

Prolactin (PRL): This hormone is under the direct control of the hypothalamus. Dopamine inhibits the release of prolactin. The suckling of the baby in the postpartum period will inhibit the release of dopamine, thus disinhibiting prolactin release. When there is a drop in dopamine levels due to disease or drugs, the patient will present with galactorrhea. Their primary function is to stimulate the growth of the mammary glands and participate in milk production.

Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH): The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) that is secreted from the hypothalamus acts on the gonadotropin cells to secrete the LH and FSH. In males, the LH acts on the Leydig cells and secretes testosterone from the testes. The FSH acts on the Sertoli cells and secretes inhibin B for spermatogenesis. In females, the LH acts on the ovaries to initiate the production of the steroid hormone, and its surge causes ovulation. FSH acts on the granulosa cells and initiates follicular development for ovulation by the mature Graafian follicle. The steroid sex hormones regulate the LH and FSH through negative feedback.

Growth Hormone or Somatotropin (GH): The GH gets secreted from the somatotrophs in response to the growth hormone-releasing hormone released from the hypothalamus. GH has anabolic properties and stimulates the growth of the cells in the body. The GH release is under the regulation of the negative feedback from the increased blood levels of GH and IGF-1.

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH): TSH secretion from the gland thyrotrophs occurs in response to the thyrotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus. This TSH acts on the thyroid gland to stimulate the release of T3 and T4. The TSH gets regulated by the blood levels of T3 and T4.[4][5][6][7]

POSTERIOR PITUITARY GLAND

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY

This portion of the gland is a specialized neuroendocrine structure. The posterior pituitary is a combination of pars nervosa and the infundibular stalk. They contain axons that have originated from hypothalamic neurons, specifically the axon terminals of the magnocellular neurons of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Glial cells called pituicytes encircle the axons. The pituicytes have elongated processes that run along with the axons; these are absent in a typical astrocyte and are due to the transcription factor expression TTF-1. The axons together form the hypothalamohypophyseal tract, which terminates near the posterior lobe sinusoids. The terminals of the axons are close to the blood vessels to aid in the secretion of the hormones. The precursor hormones are packed into secretory granules, called the herring bodies. These precursor hormones then get cleaved during transport to the posterior pituitary. Neurophysins are proteins that are essential for the posttranslational processing of hormones. The posterior pituitary is not glandular, like the anterior pituitary. Thus they do not synthesize hormones.

FUNCTION

The following are the two hormones released from the posterior pituitary.

Oxytocin: They participate in the milk let-down or milk ejection reflex during lactation, myoepithelial, and smooth muscle contraction, uterine contraction. This hormone is available for exogenous administration in patients with postpartum hemorrhage. Five IU of oxytocin is the recommended intravenous injection dosage to prevent postpartum hemorrhage, and it is given following the delivery of the anterior shoulder of the fetus.[8]

Arginine Vasopressin (AVP) or Antidiuretic Hormone (ADH): These hormones aid in the regulation of water content and prevents water depletion. It maintains the tonicity of the blood and blood pressure during an event of volume loss. The vascular smooth muscles express the V1 receptors, which, in response to the AVP, causes arteriolar contraction. The renal collecting duct and the tubular epithelium express V2 receptors, which in response to AVP, upregulate the aquaporin two channels and increases free water reuptake.[2][6][9][10]

Embryology

The pituitary gland has a dual origin. The oral ectoderm gives origin to the adenohypophysis, and the neural ectoderm gives origin to the neurohypophysis. The posterior lobe is smaller and derives from the outpouching of the third ventricle neural primordia. Thus it is an extension of the central nervous system. The organogenesis begins around the 4th week of the intrauterine development of the fetus. A hypophyseal placode forms at the oral ectoderm and gives origin to the Rathke's pouch; this develops as an upward evagination of the oral ectoderm towards the neural ectoderm to form the anterior lobe. The ventral diencephalon extends downward to form the posterior lobe. Around 6 to 8 weeks, a constriction forms at the base of the Rathke's pouch and closes completely, thus separating it from the oral epithelium. The hypothalamus communicates with the adenohypophysis through a vascular link called the hypothalamohypophyseal portal system. Meticulous coordination between the regulatory transcription factor signals is a requirement for proper pituitary gland development. There are several transcription factors such as the bone morphogenic protein four and fibroblast growth factor 8 that are necessary for the development. The notch signaling pathway has a vital role in cell lineage commitment with epigenetic regulation. SOX2 and SOC3 are involved in pituitary morphogenesis. Mutation of transcription factors such as Rpx, Prop-1, and Pit-1 can lead to a range of pituitary disorders as they are early factors that aid in organogenesis.[2][5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pituitary gland is a well-vascularized tissue, and its blood supply connects with the hypothalamus via the hypothalamohypophyseal portal system.

The superior hypophyseal artery supplies the anterior lobe. It originates from the internal carotid artery or the posterior communicating artery. Together these two arteries from the primary plexus and supply blood to the median eminence. The hypothalamic cells end at the median eminence. The primary plexuses receive regulatory factors. The capillaries form venules that lead to the formation of portal hypophyseal veins. Secondary plexuses drain into the cavernous sinus. The intermediate lobe receives its blood supply from the anastomoses between the anterior and posterior lobe capillaries. Small branches from the superior hypophyseal artery supply the pituitary stalk and parts of the optic nerve and chiasm.

The inferior hypophyseal artery supplies the posterior lobe primarily the pars nervosa, and it originates from the meningohypophyseal trunk, which is a branch of the internal carotid artery. The posterior lobe drains into the cavernous sinus.[4][11]

Surgical Considerations

There are multiple surgical approaches for the management of pituitary neoplasms. A nonfunctioning adenoma only gets surgically resected when the tumor causes compression or mass effect to the adjacent structures like the optic chiasm causing bitemporal hemianopsia field defect. This specific visual field defect is due to the compression of the nasal retinal fibers that decussate within the optic chiasm. A prolactinoma only gets surgically resected if they fail medical management with dopaminergic medications. Transsphenoidal surgery is a commonly chosen procedure for resection, especially in Cushing disease.

The transcranial, microscopic transsphenoidal, and endoscopic endonasal approaches are the different methods for surgery. Microscopic transsphenoidal surgery is the commonly used method for pituitary resection. However, the endoscopic approach is more favorable as the duration of the surgery is reduced, shorter hospital stay, is minimally invasive, has a lower chance of developing complications, and the patients experienced less post-operative pain. Researchers are studying new imaging techniques for better visualization of the adenomas using a high field intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as they may provide better spatial resolution. Stereotactic radiosurgery may have a role in patients who are not willing to repeat surgical management for recurrent or residual adenomas.[13]

Clinical Significance

The following are some of the critical disease conditions associated with the pituitary gland.

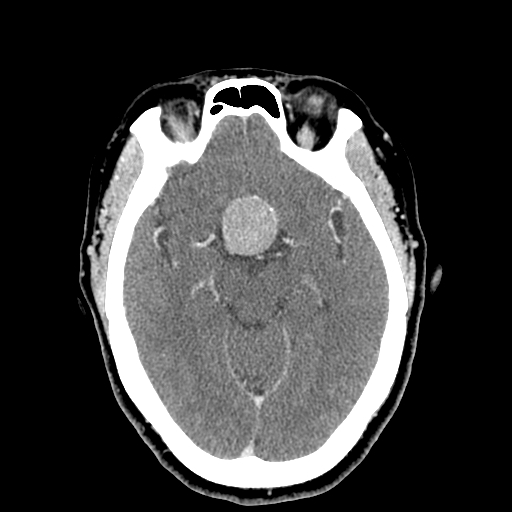

Pituitary Adenoma

The most common pathology in the sellar region is the pituitary tumor. They classify into microadenomas (less than 10 mm) and macroadenomas (more than 10 mm). These macroadenomas can compress the adjacent structures. When it extends laterally, the cavernous sinus is compressed, producing ophthalmoplegia. The patients will present with diplopia due to cranial nerve compression. They may also present asymptomatically or with headaches. All the cell lines are capable of producing an adenoma.

Prolactinoma: This is the most common type of functioning secretory adenoma. They remain asymptomatic for an extended period until they cause compression or mass effect on the normal surrounding tissue causing hormonal dysfunction, visual changes, hydrocephalus, and hypogonadism.

Cushing Disease: This results from an ACTH secreting pituitary adenoma. They present with symptoms such as proximal myopathy, psychiatric disturbances, obesity, purple striae over the abdomen, extra fat around the neck termed buffalo hump, and hypertension. The standard method for resection of the tumor is transsphenoidal adenectomy. The route is via the posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus, which forms the inferior border of the pituitary gland.

GH Secreting Adenoma: This adenoma produces a lot of GH, which can cause acromegaly or gigantism. The patient may present with carpal tunnel syndrome, proximal myopathy, and rarely hypertension or diabetes mellitus.

Stalk Compression Syndrome: The patient presents with symptoms of hyperprolactinemia with raised prolactin concentration in the presence of a sellar or suprasellar mass compressing the stalk.

Pituitary Apoplexy: Pituitary adenomas that are often asymptomatic may enlarge in size and acquire additional arterial blood supply directly and undergo hemorrhagic infarction. The clinical presentation includes abrupt onset headache, visual symptoms like diplopia due to cavernous sinus compression, panhypopituitarism with low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits. The apoplexy triad includes headaches, visual changes, and vomiting. Clinicians can misdiagnose this condition as a subarachnoid hemorrhage. An emergency CT will show an enlarged pituitary fossa with some blood, and an MRI will confirm the diagnosis.

Sheehan Syndrome: This is due to the infarction and necrosis of the pituitary gland. It can be described as postpartum hypopituitarism, as postpartum hemorrhage is closely associated with its etiology. The gland enlarges during pregnancy, which causes the superior hypophyseal artery to get compressed. If the patient experiences a drop in her blood pressure during childbirth, this causes infarction and necrosis of the gland. The patient will commonly present with failure to lactate during the postpartum period, ultimately leading to a deficiency of the anterior pituitary hormones.

Lymphocytic Hypophysitis: This condition is commonly associated with pregnancy. It is an autoimmune condition with diffuse lymphocytic infiltration that destroys normal tissue with scaring. Imaging with an MRI shows homogenously enhancing and enlarged glands.

Granulomatous Hypophysitis: This is a non-caseating granuloma with Langerhans type giant cell. When it is present in the posterior lobe, it may be due to neurosarcoidosis.

Empty Sella Syndrome: There are two types of empty sella syndrome that are differentiated according to the cause. The primary empty sella syndrome is a defect in the diaphragma sellae that allows the contents above to herniate into the sella, thus compressing the gland. The secondary empty sella syndrome is due to causes such as tumors or surgery. This syndrome is associated with multiparous women, obesity, and benign intracranial hypertension. In multiparous women, this may be due to the repeated enlargement and involution of the gland leading to the gland becoming flattened. This condition must be differentiated from craniopharyngioma and Rathke's cleft cyst as they may also present with a cyst within the same location.

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone(SIADH): This is a condition with excessive production of antidiuretic hormone, which can result from various conditions such as nervous system disorders, neoplastic, ectopic sources such as paraneoplastic syndromes, head trauma, and drugs. The patients will present with altered mental status, seizures, or even more severe cases with coma. There will be hyponatremia due to dilution with free water. The urine analysis will show increased concentration and osmolality.

Craniopharyngiomas: Two variants are classified based on clinical and genetic features, which are the adamantinomatous (aCP) and papillary (pCP) craniopharyngiomas. The aCP occurs in children, and pCP is exclusive to adults. The embryonic theory proposed states that this develops from the ectopic embryonic remnants of Rathke's pouch. The metaplastic theory states that the squamous epithelium that is part of the gland undergoes metaplasia and transforms.

Rathke’s Cleft Cyst: This is a benign cyst that originates from the mucinous substances in the remnants of Rathke's pouch. The cyst contains the pink eosinophilic substance. Due to chronic inflammation, they may develop xanthogranulomas or cholesterol crystals.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia-1(MEN-1): This is a genetic, endocrine neoplastic syndrome. There is an abnormal growth in the pituitary gland, parathyroid gland, and pancreas.[14][15][16][17]