Introduction

Phalangeal fractures of the hand are a common injury that presents to the emergency department and clinic. Injuries can occur at the proximal, middle, or distal phalanx. For the vast majority of phalanx fractures, an acceptable reduction is manageable with non-operative treatment. Early intervention is vital to allow healing and return of function. Anatomy

The proximal and middle phalanges of the hand all possess a head, neck, shaft, and base. The distal phalanx divides into the tuft, shaft, and base. The proximal phalanx receives stabilization from the surrounding anatomy, including proper and accessory collateral ligaments, volar plate, and extensor/flexor tendons. The middle phalanx has two main insertions: the central slip (extensor mechanism) and the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS). The distal phalanx anatomy includes the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ), which is enveloped by the extensor and flexor tendons along with the volar plate and collateral ligaments. The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) inserts at the volar metaphysis of the distal phalanx. At the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ), the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor digitorum superficialis are within one sheath. The flexor digitorum superficialis is volar, and the flexor digitorum profundus is dorsal. As the tendons transverse the PIPJ the flexor digitorum superficialis bifurcates into two slips that form the Camper's chiasm which inserts on the volar aspect of the middle phalanx. This important anatomic relationship can lead to a swan neck deformity (a hyperextended PIPJ and flexed DIPJ).[1]

Etiology

Injury to the phalanges occurs with direct, blunt trauma, penetrating trauma, and crush injuries.

Epidemiology

Phalanx fractures are the most common injuries in the body. They account for 10% of all fractures and 1.5% of all ED visits. The majority of trauma to the hand involves the phalanges (46% phalangeal, 36% metacarpal). The distal phalanx and border digits are most commonly injured. Males are more affected than females. The most common finger injured is the small finger.[2][3]

Pathophysiology

Phalanx fractures displace according to the level at which the fracture occurs due to the eloquent soft tissue and tendon involvement of the phalanx.

Distal Phalanx

Distal phalanx fractures are usually nondisplaced or comminuted fractures. They classify into tuft (tip), shaft, or articular injuries.

- Tuft fractures usually result from a crushing mechanism such as hitting the tip of a finger with a hammer. A tuft fracture is frequently an open fracture due to its common association with injury to the surrounding soft tissues or nail bed. Even without surrounding soft tissue injury, the fracture is considered open in the presence of a nail bed injury.

- Shaft fractures

- Intra-articular fractures are associated with extensor tendon avulsion (Mallet finger) or flexor digitorum profundus tendon avulsion (Jersey finger).[4]

- Mallet finger

- The traumatic loss of the terminal extension at the level of the DIPJ

- Jersey Finger

- Hyperextension injury with avulsion of flexor digitorum profundus[1]

- Seymour fractures: this is a displaced epiphyseal injury of the distal phalanx associated with nail bed injury. Hyperflexion is usually the mechanism of injury and it presents as a mallet deformity with apex dorsal.

Middle Phalanx

Middle phalanx fractures occur in an apex dorsal or volar angulation depending on location. Apex dorsal angulation results from the fracture occurring proximal to the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) insertion so that the fragment becomes displaced by the pull of the central slip. Apex volar angulation occurs if the fracture is distal to the flexor digitorum superficialis insertion. A fracture through the middle third may angulate in either direction or not at all as a result of the inherent stability provided by an intact and prolonged flexor digitorum superficialis insertion. Proximal Phalanx

Proximal phalanx fractures occur in an apex volar angulation (dorsal angulation). The proximal fragment flexes due to interossei, and the distal phalanx extends due to the central slip.

History and Physical

The main component to focus on assessment are:

- History - handedness, occupation, time of injury, place of injury (work-related)

- Mechanism of injury - magnitude, direction, point of contact, and type of force that caused the trauma

- Soft tissue damage

- Finger alignment - cascade, digit scissoring, rotational defect

- Open vs. Closed

- Tendon/nerve/vessel damage - tendon ruptures may accompany dislocations such as the terminal extensor tendon rupture in the distal interphalangeal joint dislocation or a central slip rupture in a proximal interphalangeal joint dislocation. Tendon damage otherwise only usually occurs with associated lacerations or open combined injuries. Nerves and vessels are rarely injured as part of a simple fracture or dislocation but often suffer injury in major open hand trauma.

Evaluation

Diagnostic tests to consider include:

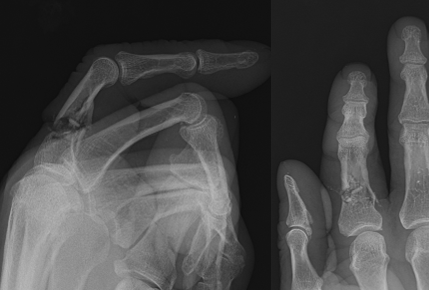

- Radiographs – PA and lateral and oblique

- CT – rarely needed. May occasionally be helpful in operative planning with complex peri-articular fractures such as pilon fractures at the base of middle phalanx fractures. It can be used to detect foreign bodies like plastic, glass, and wood.

- Ultrasound – detect objects that lack radiopacity

- MRI – unclear diagnosis, foreign material, or tumor

Mostly phalanx fractures are described by location (head, neck, shaft, base) and pattern (transverse, spiral, oblique, comminuted).[5]

Treatment / Management

Overall

The goal of surgical treatment is to allow stable reduction and early mobilization to prevent stiffness/contracture.[6]

Indications for surgical treatment are:

- Articular congruity

- Rotational malalignment

- Significant angulation/displacement

- Multiple fractures

- Open fractures

Proximal Phalanx Fractures

Non-operative

- Extraarticular with less than 10 degrees angulation or under 2 mm shortening and no rotational deformity Stable, transverse fracture

- Dorsal splinting in intrinsic plus position for 3 weeks

- Buddy taping

Operative

- Reducible but unstable isolated fractures

- Closed reduction internal fixation (CRIF)

- Intra-articular fractures with displacement

- Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF)

Closed reduction and internal fixation of proximal phalanx shaft fractures can be accomplished longitudinally through the metacarpal phalangeal joint but not the metacarpal head, or just through the metacarpal head known as Eaton-Belsky Pinning. The wires for either of these options are run in a parallel fashion, cross, or run transversely into the phalanx. Interfragmentary lag screw fixation would be indicated in long oblique fractures. Other ORIF options would be mini fragment plates and screws.

Middle Phalanx Fractures

Proximal intra-articular fractures may be comminuted with axial load and considered “pilon” fractures. If the volar portion of the proximal base fracture constitutes approximately 40% of the articular surface, then it carries the majority of the proper collateral ligament insertion. Also, the accessory ligament and volar plate insertions, which make the fracture unstable. Dorsal proximal base fractures may be considered central slip avulsions.

Non-operative

- Non-displaced

- Dynamic splinting for 2to 3 weeks

Operative

- Transverse fractures with greater than 10 degrees angulation or 2 mm shortening or rotationally deformed

- Closed reduction percutaneous pinning (CRPP) vs. ORIF

- Irreducible and unstable fractures

Distal Phalanx Fractures

- Non-operative

- Closed fractures

- Immobilize the joint, be sure to allow motion of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint.

- Minimally displaced tendon avulsion fractures

- Extensor digitorum (mallet finger)

- splint immobilization in a neutral position

- Operative

- Open fractures

- Tuft fracture is considered open in the presence of a nail bed injury. When the seal of the nail plate with the hyponychium has been broken, and the tuft fracture is displaced. This injury represents an open fracture that should receive treatment on the day of injury with debridement, followed by direct nail matrix repair. Stenting of the nail fold may be required to allow for the nail to grow [7]

- Volar subluxed mallet finger fractures involving 30% of the articular surface

- Jersey finger injuries

Differential Diagnosis

- Gout

- Osteomyelitis

- Finger infection

- Kirner deformity[8]

- Sarcoidosis[9]

- Neoplastic disease

- Endocrine disorder

- Stress fracture

Prognosis

Most phalanx fractures will heal without surgical intervention - (approximately 2% nonunion rate).

Complications

Stiffness[10]: This is the most common complication. There is an increased risk of stiffness in phalanx fractures with prolonged immobilization, intra-articular extension, and where there is extensive dissection during operative management. Stiffness is managed with hand therapy rehabilitation and surgical release would be indicated only as a last resort of management.

Malunion: Either in the form of shortening, angulation, or malrotation. Where there is functional impairment as a result of malunion, surgical intervention would be indicated. This is either in the form of corrective osteotomy at the malunion site or metacarpal osteotomy that offers limited degrees of correction.

Nonunion: Usually of the atrophic type, however, it is an uncommon complication. There are various options of management including debridement, bone grafting, and plating, fusion, or ray amputation

Loss of function

Infection

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is the key in the deterrence of phalanx fractures. Proper working conditions and safety is standardized in most work settings that decrease these injuries when working with machinery. Otherwise, trauma is difficult to control; and educating patients about signs and symptoms of phalanx fracture is an important factor for early management.

Pearls and Other Issues

To minimize tethering to extensor mechanism, use a trocar-tipped K-wire. Ensure passage of the wire through soft tissues before activating wire driver.

Understand the nature and orientation of the fracture when using the buddy taping technique. Fingers used for buddy taping include:

- Index - Long

- Long - Index

- Ring - Long

- Little - Ring

Phalanx fractures that require closed reduction and percutaneous pinning may have the procedure performed in the operating room or procedure room. The cost is significantly less in the procedure room without an increase in complications.[11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing phalanx fractures requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals that include nurses, occupational therapy, physical therapy, radiology, orthopedic surgery, and primary care physicians.

Since the majority of phalanx fractures initially present in the emergency department, the ED physician should be aware of the management and when to seek a consult from the orthopedic surgeon.

Care is taken to diagnose phalanx fractures correctly with physical exam and radiography, allowing guiding treatment to operative versus non-operative management. Regardless of the procedure, the patient has a period of immobilization, followed by an early range of motion. All patients with phalanx fractures need to be followed to ensure that healing is occurring; improper healing can affect function and quality of life. Nursing can follow up and assess the progress of treatment and subsequent therapy; reporting concerns to the clinical team. Orthopedic specialty nursing can also assist with patient and family education, as well as monitoring progress and coordinate rehab, reporting status changes to the managing clinician. Early intervention with physical therapy, whether formal or informally, will prevent stiffness and secondary complications of phalanx fractures. Ultimately, this results in better outcomes and care for the patient.[12] As is the case in all injuries, a collaborative interprofessional approach, with each specialty keeping the rest of the healthcare team informed of progress, will result in better outcomes. [Level V]