Definition/Introduction

Drug scheduling became mandated under The Federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (also known as the Controlled Substances Act). The law addresses controlled substances within Title II. Based upon this law, the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) maintains a list of controlled medications and illicit substances categorized from Schedule I to V.[1]

The five categories have their basis on the medication’s proper and beneficial medical use and the medication’s potential for dependency and misuse or abuse. The purpose of the law is to provide government oversight over the manufacturing and distribution of these substances. Prescribers and dispensers are required to have a DEA license to supply these drugs. The licensing provides links to users, prescribers, and distributors.[2][3]

Issues of Concern

The schedules range from Schedule I to V. Schedule I drugs are considered to have the highest risk of abuse, with no recognized medical use in the US, while Schedule V drugs have the lowest potential for abuse. Other factors considered by the DEA include pharmacological effect, evidenced-based knowledge of the drug, the risk to public health, trends in the use of the drug, and whether or not the drug has the potential to be made more dangerous with minor chemical modifications.

Schedule I:

- "High abuse potential with no accepted medical use; medications within this schedule may not be prescribed, dispensed, or administered"[1]

- Examples include marijuana (cannabis), heroin, mescaline (peyote), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and methaqualone.

Schedule II:

- "High abuse potential with severe psychological or physical dependence; however, these medications have an accepted medical use and may be prescribed, dispensed, or administered"[1]

- Examples include fentanyl, oxycodone, morphine, methylphenidate, hydromorphone, amphetamine, methamphetamine ("meth"), pentobarbital, and secobarbital.

- Schedule II drugs may not receive a refill at the pharmacy

Schedule III:

- "Intermediate abuse potential (ie, less than Schedule II but more than Schedule IV medications)"[1]

- examples include anabolic steroids, testosterone, and ketamine

Schedule IV:

- "Abuse potential less than Schedule II but more than Schedule V medications"[1]

- Examples include diazepam, alprazolam, and tramadol

Schedule V:

- "Medications with the least potential for abuse among the controlled substances."[1]

- Examples include pregabalin, diphenoxylate/atropine, dextromethorphan

Only Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registered practitioners can prescribe controlled substances. All prescriptions for Schedule II medications must be provided to the pharmacist in written form or transmitted by an approved computer system for electronic prescribing of controlled substances (EPCS). Several states now require EPCS systems to be used for controlled substance prescribing. A prescription for a Schedule II medication may be called in by a registered practitioner in an emergency; however, a written prescription must be provided within 7 days.[3]

Note the following tables for additional information on DEA drug schedules:

Table 1: Information regarding registration, records, prescriptions, refills, distribution, security, and theft or significant loss of controlled substances.

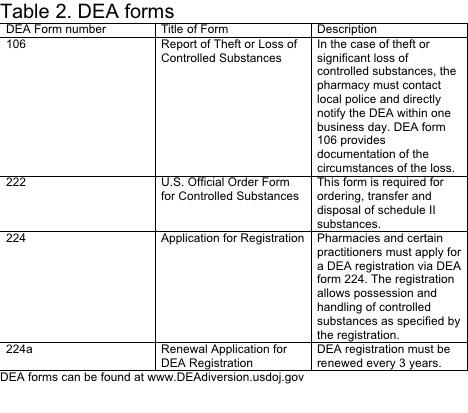

Table 2: Information regarding DEA forms 106, 222, 224, and 224a.

Clinical Significance

Medications are routinely added to the list and can be moved from one category to another as our knowledge and understanding of the medications advance. The DEA maintains a current list on its website under the diversion control division heading. Prescribers may prescribe Schedule II through V medications as allowed by their DEA and state-controlled substance or medical license.

Not all prescribers are licensed to prescribe all levels of controlled substances as their individual state or DEA licenses limit some, and other practitioners are under limitations by their professions, such as advanced practice providers in many states. The prescriber and the dispensing pharmacist are responsible for knowing each medication's category and ensuring that only properly licensed individuals prescribe the medications. Healthcare practitioners must understand the DEA controlled-substance scheduling to exercise appropriate caution when prescribing medications with high abuse potential and to ensure against prescribing outside of one's authority.[4][5]

The Controlled Substances Act has significant potential to improve patient safety by providing federal oversight for drugs with a high potential for misuse and abuse. Prescribers of scheduled substances (physicians, dentists, podiatrists, advanced practitioners) may have links to the distribution of these substances. These practitioners are required to have a DEA license and record prescriptions of scheduled drugs. This licensing prevents overprescribing and obligates providers to be wary of potential drug-seeking patients.

The dispenser must also be aware of a patient's medication history and be mindful of the potential for polypharmacy if a patient seeks multiple providers. The current opioid epidemic is a time where federal oversight and interdisciplinary coordination have the potential to reduce harm to patients prescribed scheduled drugs drastically. However, this change will take additional time and evaluation to determine if drug scheduling reduces misuse, abuse, addiction, and overdose.[6][7][8][9][10]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The healthcare team, comprised of physicians, advanced practice practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, etc, must work together to address the proper medical use of controlled substances for pain control via pharmacotherapy. The healthcare team should schedule their patients for routine follow-up visits, including a history and physical exam, to monitor for adverse drug effects and misuse.

It is also important to ensure these measures to limit controlled substances do not impair the ability of patients to obtain these medications when there is a legitimate medical need.

Monitoring for signs of drug misuse is a critical responsibility for the healthcare team because of the epidemic rates of drug misuse worldwide, particularly in the USA, which leads to death because of respiratory depression as in the case of opioid analgesic overdose (eg, oxycodone, fentanyl). Methods for monitoring drug abuse as well as drug diversion include the following examples: assessment surveys, state prescription drug monitoring programs, urine screening, adherence checklists, motivational counseling, and dosage form counting. [Level 5]