[1]

Landesberg G, Beattie WS, Mosseri M, Jaffe AS, Alpert JS. Perioperative myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009 Jun 9:119(22):2936-44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.828228. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19506125]

[2]

Pannell LM, Reyes EM, Underwood SR. Cardiac risk assessment before non-cardiac surgery. European heart journal. Cardiovascular Imaging. 2013 Apr:14(4):316-22. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes288. Epub 2013 Jan 2

[PubMed PMID: 23288896]

[3]

Biccard BM, Rodseth RN. Utility of clinical risk predictors for preoperative cardiovascular risk prediction. British journal of anaesthesia. 2011 Aug:107(2):133-43. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer194. Epub 2011 Jun 30

[PubMed PMID: 21719480]

[4]

Guarracino F, Baldassarri R, Priebe HJ. Revised ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management. Implications for preoperative clinical evaluation. Minerva anestesiologica. 2015 Feb:81(2):226-33

[PubMed PMID: 25384693]

[5]

Goldman L, Caldera DL, Nussbaum SR, Southwick FS, Krogstad D, Murray B, Burke DS, O'Malley TA, Goroll AH, Caplan CH, Nolan J, Carabello B, Slater EE. Multifactorial index of cardiac risk in noncardiac surgical procedures. The New England journal of medicine. 1977 Oct 20:297(16):845-50

[PubMed PMID: 904659]

[6]

Detsky AS, Abrams HB, Forbath N, Scott JG, Hilliard JR. Cardiac assessment for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. A multifactorial clinical risk index. Archives of internal medicine. 1986 Nov:146(11):2131-4

[PubMed PMID: 3778043]

[7]

Boersma E, Kertai MD, Schouten O, Bax JJ, Noordzij P, Steyerberg EW, Schinkel AF, van Santen M, Simoons ML, Thomson IR, Klein J, van Urk H, Poldermans D. Perioperative cardiovascular mortality in noncardiac surgery: validation of the Lee cardiac risk index. The American journal of medicine. 2005 Oct:118(10):1134-41

[PubMed PMID: 16194645]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[8]

Roshanov PS, Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, MacNeil SD, Lam NN, Hildebrand AM, Acedillo RR, Mrkobrada M, Chow CK, Lee VW, Thabane L, Garg AX. External validation of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index and update of its renal variable to predict 30-day risk of major cardiac complications after non-cardiac surgery: rationale and plan for analyses of the VISION study. BMJ open. 2017 Jan 9:7(1):e013510. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013510. Epub 2017 Jan 9

[PubMed PMID: 28069624]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[9]

Kristensen SD,Knuuti J,Saraste A,Anker S,Bøtker HE,Hert SD,Ford I,Gonzalez-Juanatey JR,Gorenek B,Heyndrickx GR,Hoeft A,Huber K,Iung B,Kjeldsen KP,Longrois D,Lüscher TF,Pierard L,Pocock S,Price S,Roffi M,Sirnes PA,Sousa-Uva M,Voudris V,Funck-Brentano C, 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). European heart journal. 2014 Sep 14

[PubMed PMID: 25086026]

[10]

Biccard B. Proposed research plan for the derivation of a new Cardiac Risk Index. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2015 Mar:120(3):543-553. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000598. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25695572]

[11]

Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, Kaushik M, Fang X, Miller WJ, Esterbrooks DJ, Hunter CB, Pipinos II, Johanning JM, Lynch TG, Forse RA, Mohiuddin SM, Mooss AN. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation. 2011 Jul 26:124(4):381-7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015701. Epub 2011 Jul 5

[PubMed PMID: 21730309]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[12]

Fronczek J, Polok K, Devereaux PJ, Górka J, Archbold RA, Biccard B, Duceppe E, Le Manach Y, Sessler DI, Duchińska M, Szczeklik W. External validation of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Myocardial Infarction and Cardiac Arrest calculator in noncardiac vascular surgery. British journal of anaesthesia. 2019 Oct:123(4):421-429. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.05.029. Epub 2019 Jun 27

[PubMed PMID: 31256916]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[13]

Gialdini G, Nearing K, Bhave PD, Bonuccelli U, Iadecola C, Healey JS, Kamel H. Perioperative atrial fibrillation and the long-term risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2014 Aug 13:312(6):616-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9143. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25117130]

[14]

Tsai A, Schumann R. Morbid obesity and perioperative complications. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2016 Feb:29(1):103-8. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000279. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26595547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[15]

Ferrante AMR, Moscato U, Snider F, Tshomba Y. Controversial results of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index in elective open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Retrospective analysis on a continuous series of 899 cases. International journal of cardiology. 2019 Feb 15:277():224-228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.031. Epub 2018 Sep 10

[PubMed PMID: 30236497]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[16]

Asuzu DT, Chao GF, Pei KY. Revised cardiac risk index poorly predicts cardiovascular complications after adhesiolysis for small bowel obstruction. Surgery. 2018 Dec:164(6):1198-1203. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.05.012. Epub 2018 Jun 24

[PubMed PMID: 29945781]

[17]

Wotton R, Marshall A, Kerr A, Bishay E, Kalkat M, Rajesh P, Steyn R, Naidu B, Abdelaziz M, Hussain K. Does the revised cardiac risk index predict cardiac complications following elective lung resection? Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2013 Dec 1:8():220. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-220. Epub 2013 Dec 1

[PubMed PMID: 24289748]

[18]

Ford MK, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN. Systematic review: prediction of perioperative cardiac complications and mortality by the revised cardiac risk index. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Jan 5:152(1):26-35. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00007. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20048269]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[19]

VISION Pilot Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Bradley D, Chan MT, Walsh M, Villar JC, Polanczyk CA, Seligman BG, Guyatt GH, Alonso-Coello P, Berwanger O, Heels-Ansdell D, Simunovic N, Schünemann H, Yusuf S. An international prospective cohort study evaluating major vascular complications among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: the VISION Pilot Study. Open medicine : a peer-reviewed, independent, open-access journal. 2011:5(4):e193-200

[PubMed PMID: 22567075]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[20]

Rodseth RN, Biccard BM, Le Manach Y, Sessler DI, Lurati Buse GA, Thabane L, Schutt RC, Bolliger D, Cagini L, Cardinale D, Chong CP, Chu R, Cnotliwy M, Di Somma S, Fahrner R, Lim WK, Mahla E, Manikandan R, Puma F, Pyun WB, Radović M, Rajagopalan S, Suttie S, Vanniyasingam T, van Gaal WJ, Waliszek M, Devereaux PJ. The prognostic value of pre-operative and post-operative B-type natriuretic peptides in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: B-type natriuretic peptide and N-terminal fragment of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jan 21:63(2):170-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1630. Epub 2013 Sep 26

[PubMed PMID: 24076282]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[21]

Duceppe E, Parlow J, MacDonald P, Lyons K, McMullen M, Srinathan S, Graham M, Tandon V, Styles K, Bessissow A, Sessler DI, Bryson G, Devereaux PJ. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Management for Patients Who Undergo Noncardiac Surgery. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2017 Jan:33(1):17-32. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.09.008. Epub 2016 Oct 4

[PubMed PMID: 27865641]

[22]

Wilcox T, Smilowitz NR, Xia Y, Berger JS. Cardiovascular Risk Scores to Predict Perioperative Stroke in Noncardiac Surgery. Stroke. 2019 Aug:50(8):2002-2006. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024995. Epub 2019 Jun 25

[PubMed PMID: 31234757]

[23]

Thomas DC, Blasberg JD, Arnold BN, Rosen JE, Salazar MC, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW. Validating the Thoracic Revised Cardiac Risk Index Following Lung Resection. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017 Aug:104(2):389-394. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.02.006. Epub 2017 May 9

[PubMed PMID: 28499655]

[24]

Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators, Spence J, LeManach Y, Chan MTV, Wang CY, Sigamani A, Xavier D, Pearse R, Alonso-Coello P, Garutti I, Srinathan SK, Duceppe E, Walsh M, Borges FK, Malaga G, Abraham V, Faruqui A, Berwanger O, Biccard BM, Villar JC, Sessler DI, Kurz A, Chow CK, Polanczyk CA, Szczeklik W, Ackland G, X GA, Jacka M, Guyatt GH, Sapsford RJ, Williams C, Cortes OL, Coriat P, Patel A, Tiboni M, Belley-Côté EP, Yang S, Heels-Ansdell D, McGillion M, Parlow S, Patel M, Pettit S, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2019 Jul 29:191(30):E830-E837. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190221. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31358597]

[25]

Bertges DJ, Goodney PP, Zhao Y, Schanzer A, Nolan BW, Likosky DS, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Cronenwett JL, Vascular Study Group of New England. The Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Risk Index (VSG-CRI) predicts cardiac complications more accurately than the Revised Cardiac Risk Index in vascular surgery patients. Journal of vascular surgery. 2010 Sep:52(3):674-83, 683.e1-683.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.031. Epub 2010 Jun 8

[PubMed PMID: 20570467]

[26]

Alrezk R, Jackson N, Al Rezk M, Elashoff R, Weintraub N, Elashoff D, Fonarow GC. Derivation and Validation of a Geriatric-Sensitive Perioperative Cardiac Risk Index. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2017 Nov 16:6(11):. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006648. Epub 2017 Nov 16

[PubMed PMID: 29146612]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[27]

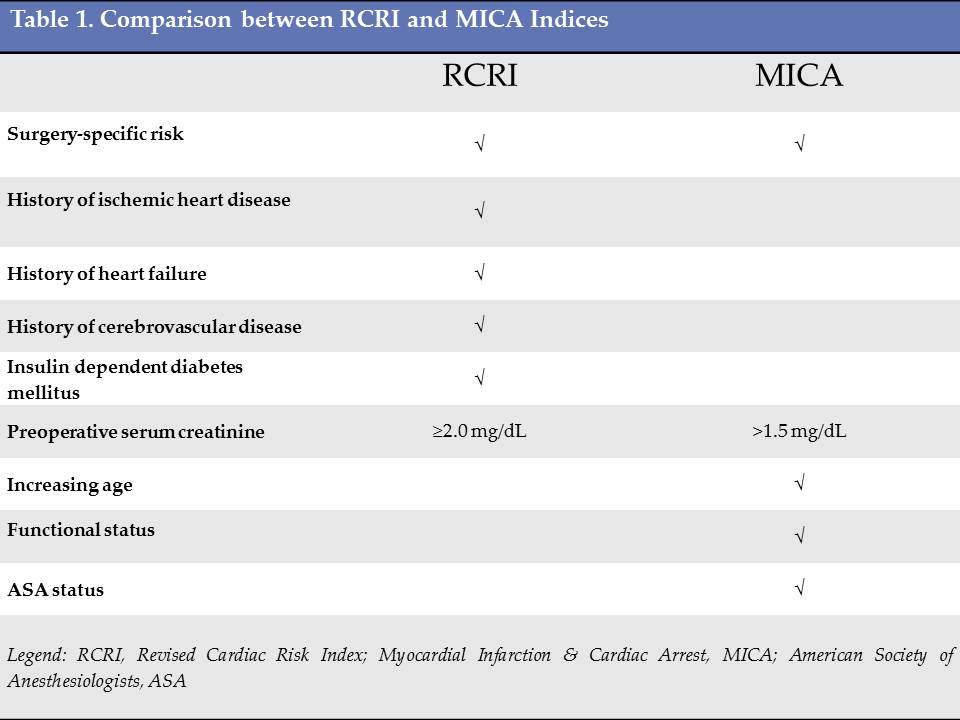

Dakik HA, Chehab O, Eldirani M, Sbeity E, Karam C, Abou Hassan O, Msheik M, Hassan H, Msheik A, Kaspar C, Makki M, Tamim H. A New Index for Pre-Operative Cardiovascular Evaluation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Jun 25:73(24):3067-3078. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.023. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31221255]

[28]

Sabaté S, Mases A, Guilera N, Canet J, Castillo J, Orrego C, Sabaté A, Fita G, Parramón F, Paniagua P, Rodríguez A, Sabaté M, ANESCARDIOCAT Group. Incidence and predictors of major perioperative adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in non-cardiac surgery. British journal of anaesthesia. 2011 Dec:107(6):879-90. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer268. Epub 2011 Sep 2

[PubMed PMID: 21890661]